Understanding Good Jobs a Review of Definitions and Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Job Strain and Self-Reported Insomnia Symptoms Among Nurses: What About the Influence of Emotional Demands and Social Support?

Hindawi Publishing Corporation BioMed Research International Volume 2015, Article ID 820610, 8 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/820610 Research Article Job Strain and Self-Reported Insomnia Symptoms among Nurses: What about the Influence of Emotional Demands and Social Support? Luciana Fernandes Portela,1 Caroline Kröning Luna,2 Lúcia Rotenberg,2 Aline Silva-Costa,2 Susanna Toivanen,3 Tania Araújo,4 and Rosane Härter Griep2 1 National School of Public Health (ENSP/Fiocruz), Avenida Brasil 4365, 21040-360 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 2Health and Environmental Education Laboratory, Oswaldo Cruz Institute (IOC/Fiocruz), Avenida Brasil 4365, 21040360 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 3Centre for Health Equity Studies (CHESS), Stockholm University and Karolinska Institute, Sveaplan, Sveavagen¨ 160, Floor 5, 106-91 Stockholm, Sweden 4Department of Health, State University of Feira de Santana, R. Claudio´ Manoel da Costa 74/1401, Canela, 40110-180Salvador,BA,Brazil Correspondence should be addressed to Luciana Fernandes Portela; [email protected] Received 16 January 2015; Revised 8 April 2015; Accepted 8 May 2015 Academic Editor: Sergio Iavicoli Copyright © 2015 Luciana Fernandes Portela et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Job strain, derived from high psychological demands and low job control, is associated with insomnia, but information on the role of emotional demands and social support in this relationship is scarce. The aims of this study were (i) to test the association between job strain and self-reported insomnia symptoms, (ii) to evaluate the combination of emotional demands and job control regarding insomnia symptoms, and (iii) to analyze the influence of social support in these relationships. -

A Perfect Storm? Reimagining Work in the Era of the End of the Job

EPIC 2014 | Paper Session 1: Ethnographic Cases A Perfect Storm? Reimagining Work in the Era of the End of the Job MELISSA CEFKIN IBM Research OBINNA ANYA IBM Research ROBERT MOORE IBM Research Trends of independent workers, an economy of increasingly automated processes and an ethos of the peer-to-peer “sharing economy” are all coming together to transform work and employment as we know them. Emerging forms of “open” and “crowd” work are particularly keen sites for investigating how the structures and experiences of work, employment and organizations are changing. Drawing on research and design of work in organizational contexts, this paper explores how experiences with open and crowd work systems serve as sites of workplace cultural re- imagining. A marketplace, a crowdwork system and a crowdfunding experiment, all implemented within IBM, are examined as instances of new workplace configurations. “It’s like old age. It’s the worst thing, except the alternative.” (A local farmer when asked to take on more work in Downton Abbey, Season 4) INTRODUCTION: WHITHER THE JOB, LONG LIVE WORK! A perfect storm in the world of work may be forming. Consider the following dynamics. In the United States, the Affordable Care Act is projected to enable freedom from job lock, or the need to stick with an employer primarily for benefits, particularly health insurance (Dewan 2014) This comes on the heels of the Great Recession which has pushed many into “the independent workforce” a population some already consider undercounted, under- represented (Horowitz 2014) and likely growing (MBO Partners 2013, US Government Accountability Office 2006). -

Association Between Job Strain and Prevalence of Hypertension

Occup Environ Med 2001;58:367–373 367 Occup Environ Med: first published as 10.1136/oem.58.6.367 on 1 June 2001. Downloaded from Association between job strain and prevalence of hypertension: a cross sectional analysis in a Japanese working population with a wide range of occupations: the Jichi Medical School cohort study A Tsutsumi, K Kayaba, K Tsutsumi, M Igarashi, on behalf of the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study Group Abstract Keywords: hypertension; stress; psychological; work Objectives—To explore the association between the prevalence of hypertension in a Japanese working population and job Comprehensive reviews conclude that job strain (a combination of low control over strain, a combination of low control over the work and high psychological demands), job and high psychological demands, is related to the incidence and prevalence of cardiovas- and to estimate this association in diVer- 1–3 ent sociodemographic strata. cular diseases in western countries. It was Methods—From a multicentre commu- postulated that one of the underlying mecha- nisms through which job strain leads to cardio- nity based cohort study of Japanese peo- vascular diseases is high blood pressure due to ple, sex specific cross sectional analyses chronic physiological arousal.2 Several studies were performed on 3187 men and 3400 have been conducted to substantiate this women under 65 years of age, all of whom hypothesis; and evidence has been accumulat- were actively engaged in various occupa- ing to prove a cause-eVect relation between job tions throughout Japan. The baseline strain and high blood pressure.4–8 However, the period was 1992–4. -

Breaking Job Lock (Kimbrell)

Breaking The Job Lock: Imagine A World Where Pursuing Our Passions Pays the Bills By Andrew Kimbrell The alarm clock explodes with a high-pitched screech. It is 6:30 a.m.--another dreaded Monday. Kids need to be dressed, fed, rushed off to school. Then there is 40 minutes of fighting traffic and the sprint from the parking lot to your workstation. You arrive, breathless, just in the nick of time. Now is the moment to confront the week ahead. As usual, you are in overload mode. You seem to be working faster and faster but falling farther behind. What is worse, your unforgiving bosses think everything gets accomplished by magic. But you do not dare do or say anything that might jeopardize your job. (It hurts just to think of those swelling credit card balances.) At the end of the day, when you are drained and dragged out, it is time to endure the long drive home, get dinner ready, and maybe steal a few hours in front of the TV. Then to sleep, and it starts all over again. Sound familiar? Despite utopian visions earlier in this century of technology freeing us all from the toil of work, we are now working harder than ever--with little relief in sight. In a recent poll, 88 percent of workers said their jobs require them to work longer (up from 70 percent 20 years ago), and 68 percent complained of having to work at greater speeds (up from 50 percent in 1977). And as if all this were not grim enough, the most discouraging aspect of our jobs is that they seem to accomplish little of lasting value. -

![[Job] Locked and [Un]Loaded: the Effect of the Affordable Care Act Dependency Mandate on Reenlistment in the U.S. Army](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1999/job-locked-and-un-loaded-the-effect-of-the-affordable-care-act-dependency-mandate-on-reenlistment-in-the-u-s-army-1171999.webp)

[Job] Locked and [Un]Loaded: the Effect of the Affordable Care Act Dependency Mandate on Reenlistment in the U.S. Army

Upjohn Institute Policy and Research Briefs Upjohn Research home page 4-2-2019 [Job] Locked and [Un]loaded: The Effect of the Affordable Care Act Dependency Mandate on Reenlistment in the U.S. Army Michael S. Kofoed United States Military Academy Wyatt J. Frasier United States Army Follow this and additional works at: https://research.upjohn.org/up_policybriefs Part of the Labor Economics Commons Citation Kofoed, Michael S. and Wyatt J. Frasier. 2019. "[Job] Locked and [Un]loaded: The Effect of the Affordable Care Act Dependency Mandate on Reenlistment in the U.S. Army." Policy Brief. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://doi.org/10.17848/pb2019-7 This title is brought to you by the Upjohn Institute. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARCH 2019 POLICY BRIEF [Job] Locked and [Un]loaded The Effect of the Affordable Care Act Dependency Mandate on Reenlistment in the U.S. Army Michael S. Kofoed and Wyatt J. Frasier BRIEF HIGHLIGHTS One concern that policymakers have regarding employer-sponsored health insurance is “job lock” and its effects on labor markets. Workers value health benefits, but n We test whether access to parents’ health benefits are not transferable across jobs. Thus, a worker could want to pursue health insurance led soldiers to not a more desirable job opportunity but may choose not to because that worker might reenlist in the Army. lose her health insurance coverage. This condition could cause a worker to forgo career satisfaction or promotion or advancement. Policymakers worry about this n The ACA allowed people under phenomenon because it may limit worker effectiveness and lower the incentive toward age 26 to stay on their parents’ health entrepreneurship. -

T-98 Statement Before the House Ways and Means Committee

T-98 Statement Before the House Ways and Means Committee , Subcommittee on Health Hearing on Health Insurance Portability by Paul Fronstin, Research Associate Employee Benefit Research Institute Washington, D.C. 12May 1995 The views expressed in this statement are solely those of the author and should not be attributed to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, its officers, trustees, sponsors_, or other staff. The Employee Benefit Research Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, public policy research organization. Suite 600 ._ 2121 K Street. NW Washington. DC 20037-1896 202-659-0670 Fax 202-775-6312 SIJI-_IARY •The original purpose of the coverage continuation provisions of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) was to assure workers an ability to maintain health insurance during a period of transition to other coverage. COBRA requires employers to offer continued health coverage to employees and their dependents when certain qualifying events occur. • Of the 14.5 percent of employees and dependents eligible for COBRA coverage, about 1 in 5 (19.6 percent) elected the coverage, according to 1994 survey data, up from 19.3 percent in 1993 but down from a high of 28.5 percent in 1990. • Average COBRA costs were $5,584, compared with $3,903 for active employees, according to the 1994 survey. Thus, average continuation of coverage costs were 149 percent of active employee claims costs, and, assuming employees electing coverage were paying 102 percent of the premium, employers were paying for approximately one-third (32 percent) of the total costs for continued coverage. • Difficulties surrounding COBRA coverage according to survey respondents included adverse selection/claims cost (36 percent); difficulties in collecting premiums (36 percent); administrative difficulty such as paperwork, record keeping, etc. -

Job Characteristics and Job Retention of Young Workers with Disabilities

Job Characteristics and Job Retention of Young Workers with Disabilities Carrie L. Shandra Department of Sociology State University of New York at Stony Brook [email protected] People with disabilities experience significantly lower levels of labor force participation than people without disabilities in the United States. Despite the focus on work promotion among this population, comparatively less is known about the factors promoting job retention among contemporary cohorts of young workers with disabilities. This study utilizes data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97) to examine the following: How do job characteristics differ by disability status? What job characteristics associate with the hazard of separation among young workers with disabilities? And, do the characteristics associated with the hazard of separation differ by disability status? I utilize Cox regression and longitudinal employment histories of workers from labor market entry through the early 30s. Results indicate that young workers with disabilities have a higher baseline hazard of separation than workers with disabilities—both overall and when considering voluntary and involuntary reasons for job exit. These results persist for involuntary separations (among those with serious disability) and voluntary health-related separations (among those with mild or serious disability) even after controlling for job characteristics. Employment benefits—including medical benefits, flexible scheduling, unpaid leave, and retirement—negatively associate with the hazard of separation for workers with disabilities. However, these effects persist for all workers, whereas job satisfaction, job sector, and work hours further condition the hazard of separation among workers with disabilities. Draft 08/20/18 I gratefully acknowledge support from the Department of Labor Scholars Program, 2017-2018, the staff at Avar Consulting, and seminar attendees at the Department of Labor. -

The Affordable Care Act and the Labor Market: a First Look

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports The Affordable Care Act and the Labor Market: A First Look Maxim Pinkovskiy Staff Report No. 746 October 2015 This paper presents preliminary findings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author. The Affordable Care Act and the Labor Market: A First Look Maxim Pinkovskiy Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 746 October 2015 JEL classification: I13, I18 Abstract I consider changes in labor markets across U.S. states and counties around the enactment of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 and its implementation in 2014. I find that counties with large fractions of uninsured (and therefore a large exposure to the ACA) before the enactment or the implementation of the ACA experienced more rapid employment and salary growth than did counties with smaller fractions of people uninsured, both after the implementation of the ACA and after its enactment. I also find that the growth of the fraction of employees in states with larger uninsurance rates was not substantially higher than it was in states with smaller uninsurance rates. These findings are not accounted for by differential rates of recovery from the Great Recession in high- and low-uninsurance areas. Key words: labor economics, health economics _________________ Pinkovskiy: Federal Reserve Bank of New York (e-mail: [email protected]). -

An Investigation of the Impact of Abusive Supervision on Technology End-Users

OC13003 An investigation of the impact of abusive supervision on technology end-users Kenneth J. Harris Indiana University Southeast Kent Marett Mississippi State University Ranida B. Harris Indiana University Southeast Abstract Although they are likely to occur in many organizations, few research efforts have examined the impact of negative supervisor behaviors on technology end-users. In this study we investigate abusive supervision, and the effects it has on perceptions about the work and psychological, attitudinal, and behavioral intention outcomes. Our sample consisted of 225 technology end- users from a large variety of organizations. Results revealed that abusive supervision has a positive impact on perceived pressure to produce, time pressure, and work overload, and a negative impact on liking computer work, and ultimately these variables impact job strain, frustration, turnover intentions, and job satisfaction. KEYWORDS: abusive supervision, computer workers, job strain, turnover intentions, frustration OC13003 An investigation of the impact of abusive supervision on technology end-Users Employees in all business functional areas, including information systems, have experienced a supervisor giving his or her subordinates the silent treatment, publicly ridiculing them or being rude towards them, expressing anger at them when they are not the source of the anger, or making negative comments about them to others. Unsurprisingly, these abusive behaviors are likely to have considerable negative effects for the subordinates experiencing -

The Effect of Job Strain in the Hospital Environment: Applying Orem's Theory of Self Care

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 The Effect Of Job Strain In The Hospital Environment: Applying Orem's Theory Of Self Care Diane Andrews University of Central Florida Part of the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Andrews, Diane, "The Effect Of Job Strain In The Hospital Environment: Applying Orem's Theory Of Self Care" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 757. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/757 THE EFFECT OF JOB STRAIN IN THE HOSPITAL ENVIRONMENT: APPLYING OREM’S THEORY OF SELF-CARE by DIANE RANDALL ANDREWS B.S.N. University of Iowa, 1976 M.S. University of Illinois, 1981 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Public Affairs Program in the College of Health and Public Affairs at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2006 Major Professor: Thomas T. H. Wan © 2006 Diane Randall Andrews ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this research was to evaluate the causal relationships between job strain, the practice environment and the use of coping skills in order to assist in the prediction of nurses who are at risk for voluntary turnover. -

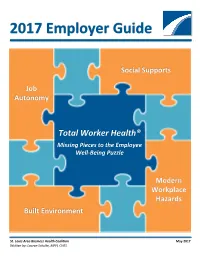

2017 Employer Guide Total Worker Health® Missing Pieces to The

2017 Employer Guide Social Supports Job Autonomy Total Worker Health® Missing Pieces to the Employee Well-Being Puzzle Modern Workplace Hazards Built Environment St. Louis Area Business Health Coalition May 2017 Written by: Lauren Schulte, MPH, CHES Introduction Total Worker Health® (TWH) is defined as policies, programs, and practices that integrate protection from work-related safety and health hazards with the promotion of injury and illness prevention to advance worker well-being.8 It goes beyond an employee’s risk status and family history to consider those upstream, job-related factors that may impact an individual’s health and well-being. TWH strategies not only protect employees from physical, mental, and operational hazards of the workplace but also explore mechanisms to help employees become their happiest, most energized, and productive selves. Modern Workplace Hazards When occupational safety and health first became a priority in the 1970s, worker deaths due to on-the-job accidents, chemical exposures, and dangerous environments were at an all-time high.9 Although regulations and policies have been enacted to assure safe and healthful working conditions for employees, developments of 21st century have introduced a host of new workplace hazards that threaten the well-being of modern workers. Sedentary jobs have Technology advances, Job insecurity and increased by 83% since including cell phones and employment stress have 1950. Referred to as email, have allowed work been heightened as “sitting disease,” this level to extend -

Job Stress and Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease

Ⅵ Karoshi (Death from Overwork) Job Stress and Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease JMAJ 47(5): 222–226, 2004 Fumio KOBAYASHI Professor, Department of Health and Psychosocial Medicine, School of Medicine, Aichi Medical University Abstract: Repetitive or long-lasting effects of work stressors cause a type of exhaustion referred to as “accumulated fatigue,” that may eventually cause ische- mic heart disease or stroke. Among the various work stressors to which people may be exposed, long work hours combined with lack of sleep is a major risk factor in our society. Irregular work hours, shift work, frequent work-related trips, working in a cold or noisy environment, and jet lag are also potent risk factors for workers. In addition, the chronic effects of psychological job strain, which can be concep- tualized by the job demand-control-support model, are related to cardiovascular disease. In this model, high job demand and low work control accompanied by low social support at work are the most harmful to health. However, the biomedical mechanisms connecting psychological job strain to cardiovascular disease remain to be fully clarified. Key words: Job stress; Cardiovascular disease; Long hour work; Job strain The Concept of Work Stress ‘stress reactions’. There are various stress reac- tions, including psychological responses (de- The Occupational Stress Model1) of National pression and dissatisfaction at work), physio- Institute of Occupational Safety and Health logical responses (blood pressure elevation and (NIOSH) is shown in Fig. 1 to facilitate under- increased heart rate), and behavioral responses standing of the concept of work stress and its (overeating, overdrinking, smoking, drug use, effect.