Landscape Character Assessment Tayside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasonal and Temporary Vacancies in Angus Burnside Farm • Location

Seasonal and Temporary Vacancies in Angus Burnside Farm • Location: East Memus, Forfar, Angus, DD8 3TY • Roles: Soft Fruit Picker • Start and finish dates: From May to October • Salary: From £8.72 per hour • Specific skills required: None required • How to apply: Email [email protected] or online at jobs.angusgrowers.co.uk D and J Warden • Location: North Mains of Dun, Montrose, Angus, DD10 9LW • Roles: Soft Fruit Picker • Start and finish dates: From May to October • Salary: From £8.72 per hour • Specific skills required: None required • Additional information: D&J Warden is farmed in partnership with David and Jenny, we are 1st generation farmers. At North Mains of Dun we produce strawberries, blackberries, raspberries and blueberries for Angus Soft Fruits. • How to apply: Email [email protected] or online at jobs.angusgrowers.co.uk East Seaton Farm • Location: East Seaton Farm, Arbroath, Angus, DD11 5SD • Roles: Soft Fruit Picker • Start and finish dates: From April to October • Salary: From £8.72 per hour • Specific skills required: None required • Additional information: East Seaton Farm is one of the leading growers of soft fruit in Scotland. Owned by Lochart and Debbie Porter. East Seaton was formed in 1991 as a soft fruit farm and continues to produce high quality fruit for 6 months of the year. • How to apply: Email [email protected] or online at jobs.angusgrowers.co.uk www.eastseatonfarm.co.uk JG Porter • Location: Milldam Woodhill Farm, Carnoustie, Angus, DD7 7SB • Roles: Soft Fruit Picker • Start and finish dates: From April to October • Salary: From £8.72 per hour • Specific skills required: None required • Additional information: At Balhungie we grow 31 acres of strawberries, 14 acres of raspberries, 150 acres of potatoes and 600 acres of cereal crops. -

Highland Perthshire Trail

HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE TRAIL HISTORY, CULTURE AND LANDSCAPES OF HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE THE HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE TRAIL - SELF GUIDED WALKING SUMMARY Discover Scotland’s vibrant culture and explore the beautiful landscapes of Highland Perthshire on this gentle walking holiday through the heart of Scotland. The Perthshire Trail is a relaxed inn to inn walking holiday that takes in the very best that this wonderful area of the highlands has to offer. Over 5 walking days you will cover a total of 55 miles through some of Scotland’s finest walking country. Your journey through Highland Perthshire begins at Blair Atholl, a small highland village nestled on the banks of the River Garry. From Blair Atholl you will walk to Pitlochry, Aberfeldy, Kenmore, Fortingall and then to Kinloch Rannoch. Several rest days are included along the way so that you have time to explore the many visitor attractions that Perthshire has to offer the independent walker. Every holiday we offer features hand-picked overnight accommodation in high quality B&B’s, country inns, and guesthouses. Each is unique and offers the highest levels of welcome, atmosphere and outstanding local cuisine. We also include daily door to door baggage transfers, route notes and detailed maps and Tour: Highland Perthshire Trail pre-departure information pack as well as emergency support, should you need it. Code: WSSHPT1—WSSHPT2 Type: Self-Guided Walking Holiday Price: See Website HIGHLIGHTS Single Supplement: See Website Dates: April to October Walking Days: 5—7 Exploring Blair Castle, one of Scotland’s finest, and the beautiful Atholl Estate. Nights: 6—8 Start: Blair Atholl Visiting the fascinating historic sites at the Pass of Killiecrankie and Loch Tay. -

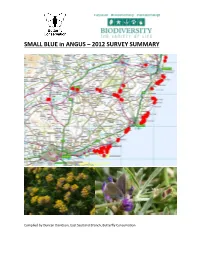

SMALL BLUE in ANGUS – 2012 SURVEY SUMMARY

SMALL BLUE in ANGUS – 2012 SURVEY SUMMARY Compiled by Duncan Davidson, East Scotland Branch, Butterfly Conservation Introduction The Small Blue is a UKBAP priority species, which has suffered severe declines in recent decades. This project was set up to help understand the butterfly’s status in Angus and to achieve the following aims over a five year period: gain a definitive view of the distribution of the butterfly and its foodplant, Kidney Vetch identify new and potential sites generate awareness with landowners and others develop plans for the conservation and extension of colonies 2012 was the first year of the project, when it was planned to survey historical sites and identify potential action sites. As a first step, the county was divided into survey areas and volunteers chose particular areas of interest. This was initiated at a volunteer training day in Arbroath, where there was a enthusiastic turnout of 14 volunteers. The following survey areas were designated: Barry Buddon & Carnoustie East Haven to Elliot Seaton Cliffs Lunan Bay, Ethie to Usan Montrose & Kinnaber Friockheim to Balgavies Forfar Glamis Barry Buddon & Carnoustie Because Barry Buddon is a military site, access can be difficult and it was planned that survey work would take place during the annual visit arranged through Dundee Nats and others, on 24 June. In the event, there were five separate sightings of Small Blue and one volunteer recorded Kidney Vetch in a number of other areas. It took one volunteer five visits to Carnoustie dunes before he saw a handful of Small Blue butterflies on 19 June, so sometimes perseverance is required. -

Committee Minutes 12Th March 2020

May Meeting Postponed Glenlyon and Loch Tay Community Council Draft minutes of the meeting held on 12th March 2020 at Fortingall Present: S.Dolan – Betney (chair), J. Riddell (treasurer), S. Dorey (secretary), J. Polakowska, Cllr J.Duff and 11 members of the public Apologies: K. Douthwaite, W. Graham, Cllr M. Williamson, C. Brook, E. Melrose. Minutes of the meeting held on 9.1.2020 in Fearnan were agreed, proposed by JP, seconded by JR. Finance: Current balance is £363.30 Police Report: Due to operational problems there was no-one available from Police Scotland. No new issues to report. Fearnan sub-area: just waiting for a map, then straightforward. Proposed LDP2 – no specific policies on ‘hutting’. JD provided paper copy of Policy 49:Minerals and Other Extractive Activities – Supply “Financial Guarantees for Mineral Development Supplementary Guidance”, Consultation draft. Closing date for comment March 16th 2020. Roads: Pop up Police Officers – risk assessment to be done prior to locating them near Lawers Hotel & the A827 in Fearnan. Fearnan verge-masters have now been installed by PKC at Letterellan. Glen Lyon road closure now will be June, instead of January. The hill road still the alternative route. Will need work to make it safe, as mentioned by a local resident. Cllrs JD & MW will ensure this happens. Timber Transport Fund will look at a possibility of funding to improve the lay -byes on the Glen road and to widen is slightly, where there are no concealed utility cables, pipes, etc. Flooding near Keltneyburn at Wester Blairish water is flowing over the road which causes problems when it freezes, due, probably, to a blocked field drain. -

Dundeeuniversi of Dundee Undergraduate Prospectus 2019

This is Dundee Universi of Dundee Undergraduate Prospectus 2019 One of the World’s Top 200 Universities Times Higher Education World Universi Rankings 2018 This is Dundee Come and visit us Undergraduate open days 2018 and 2019 Monday 27 August 2018 Saturday 22 September 2018 Monday 26 August 2019 Saturday 21 September 2019 Talk to staff and current students, tour our fantastic campus and see what the University of Dundee can offer you! Booking is essential visit uod.ac.uk/opendays-ug email [email protected] “It was an open day that made me choose Dundee. The universities all look great and glitzy on the prospectus but nothing compares to having a visit and feeling the vibe for yourself.” Find out more about why MA Economics and Spanish student Stuart McClelland loved our open day at uod.ac.uk/open-days-blog Contents Contents 8 This is your university 10 This is your campus 12 Clubs and societies 14 Dundee University Students’ Association 16 Sports 18 Supporting you 20 Amazing things to do for free (or cheap!) in Dundee by our students 22 Best places to eat in Dundee – a students’ view 24 You’ll love Dundee 26 Map of Dundee 28 This is the UK’s ‘coolest little city’ (GQ Magazine) 30 Going out 32 Out and about 34 This is your home 38 This is your future 40 These are your opportunities 42 This is your course 44 Research 46 Course Guide 48 Making your application 50 Our degrees 52 Our MA honours degree 54 Our Art & design degrees 56 Our life sciences degrees 58 Studying languages 59 The professions at Dundee 60 Part-time study and lifelong learning 61 Dundee is international 158 Advice and information 160 A welcoming community 161 Money matters 162 Exchange programmes 164 Your services 165 Where we are 166 Index 6 7 Make your Make This is your university This is your Summer Graduation in the City Square Summer Graduation “Studying changes you. -

Plot of Land, Drummygar Farm

Plot of land, Drummygar Farm CARMYLLIE, ARBROATH, ANGUS, DD11 2RA 01382 721 212 The plot is located in the rural hamlet of Carmyllie and is convenient for a range of local amenities and services at the Angus townships whilst there are mainline railway stations in Arbroath, Carnoustie and Dundee. The Angus glens are within reach, offering a plentiful range of outdoor pursuits, as are beautiful coastal beaches including Lunan Bay and world-renowned golf courses. The city of Dundee is nearby offering a full range of shops, cafes and restaurants, professional services, Universities, and vibrant arts and cultural facilities. With outstanding country and sea views, this plot is approximately 1334 sq.m with outline planning for a 1 1/2 storey dwelling house. The plot also features an unlisted, traditional stone bothy which could offer further development opportunity, in addition to a bespoke, new-build home. Alternatively, full design and build packages may be available from rural design companies such as R.House, offering complete turnkey solutions. Timber frame companies such as Scotframe also offer a range of pre-designed home styles. Please call us for further information. Officerʼs ID / Date TITLE NUMBER LAND REGISTER 4946 OF SCOTLAND 23/4/2013 ANG54978 N ORDNANCE SURVEY 140m NATIONAL GRID REFERENCE Survey Scale NO5543 NO5544 1/2500 Disclaimer: The copyright for all photographs, fl oorplans, graphics, written copy and images belongs to McEwan Fraser Legal and use by others or transfer to third parties is forbidden without our express consent in writing. Prospective purchasers are advised to have their interest noted through their solicitor as soon as possible in order that they may be informed in the event of an early closing date being set for the receipt of offers. -

Memorandum Regarding the Fairweathers of Menmuir Parish

4- Ilh- it National Library of Scotland *B000448350* 7& A 7^ JUv+±aAJ icl^^ MEMORANDUM REGARDING THE FAIRWEATHER'S OF MENMUIR PARISH, FORFARSHIRE, AND OTHERS OF THE SURNAME, BY ALEXANDER FAIRWEATHER. EDITED, WITH NOTES, ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS, BY WILLIAM GERARD DON, M.D. PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION LONDON : Dunbar & Co., 31, Marylebone Lane, W 1898. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/memorandumregard1898fair CONTENTS I. Introductory. II. Of the Name in General. III. Of the Angus Fairweathers. APPENDICES. I. Kirriemuir Fairweathers. II. Intermarriage, Dons, Fairweathers, Leightons. III. Intermarriage, Leightons, Fairweathers. IV. Intermarriage, Smiths, Fairweathers. V. List of Fairweathers. VI. Fairweathers of Langhaugh. VII. Fairweathers Mill of Ballhall. VIII. Christian Names, Fairweathers. IX. Occupations, Fairweathers. — ; INTRODUCTORY. LEXANDER FAIRWEATHER, at one time Merchant in Kirriemuir, afterwards resident at Newport, Dundee, about the year 1874, wrote this Memorandum, or History ; to which he proudly affixed the following lines : " Our name and ancestry renowned or no, Free from dishonour, 'tis our pride to show." As his memorandum exists only in manuscript, and so might easily be lost, I proprose to re-edit it for printing ; with such notes, and corrections as I can furnish. Mr. Fairweather had sound literary tastes, and was a keen archaeologist and genealogist ; upon which subjects he brought to bear a considerable amount of critical acumen. The deep interest he took in everything connected with his family and surname naturally endeared him to all his kin while, unfailing geniality and lively intelligence, made him a wide circle of attached friends, ! ; 6 I only met him once, when he visited Jersey in 1876 where I happened to be quartered, with the Royal Artillery, and where he sought me out. -

Chapter 27 Our Lyon Family Ancestry

Chapter 27 Our Lyon Family Ancestry Introduction Just when I think I have run out of ancestors to write about, I find another really interesting one, and that leads to another few weeks of research. My last narrative was about our Beers family ancestors, going back to Elizabeth Beers (1663-1719), who married John Darling Sr. (1657-1719). Their 2nd-great granddaughter, Lucy Ann Eunice Darling (1804-1884), married Amzi Oakley (1799-1853). Lucy Ann Eunice Darling’s parents were Samuel Darling (1754- 1807) and Lucy Lyon (1760-1836). All of these relationships are detailed in the section of the “Quincy Oakley” family tree that is shown below: In looking at this part of the family tree, I realized that I knew absolutely nothing about Lucy Lyon [shown in the red rectangle in the lower-right of the family tree on the previous page] other than the year she was born (1760) and the year she died (1836). I didn’t even know where she lived (although Fairfield County, Connecticut, would have been a good guess). What was her ancestry? When did her ancestors come to America? Where did they live before that? To whom are we related via the Lyon family connection? So after another few weeks of work, I now can tell her story. And it is a pretty good one! The Lyon Family in Fairfield, Connecticut Lucy Lyon was descended from Richard Lyon Jr. (1624-1678), who was one of three Lyon brothers who emigrated from Scotland in the late 1640’s. In 1907, a book was published about this family, entitled Lyon Memorial, and of course, it has been digitized and is available online:1 1 https://archive.org/details/lyonmemorial00lyon The story of the three Lyon brothers (Henry, Thomas, and Richard Jr.) in the New World begins with the execution (via beheading) of King Charles I in London, England, on 30 January 1649 (although the Lyon Memorial book has it as 1648). -

Friends of Dundee Law Welcome Pack

Friends of Dundee Law Welcome pack With its breath taking views across the city, historical features and tranquil woodland walks, the Law is a special place, treasured by Dundonians of all ages. The Dundee TWIG project agrees that the Law is a fantastic green space and feel that local people should have a greater involvement in what happens on the Law and play a vital role in its management and development. In order to help local people become more involved in positive action on the Law, we are looking to form a Friends of Dundee Law group. Anyone with an interest in the Law is welcome to join the group which will be supported by the Council’s Environment Department and Community Officers. To kick start the project, Forestry Commission Scotland have provided a grant through the Community Seedcorn Fund. This will support the group’s activities and events throughout the first year. Additionally, the Environment Department are currently putting together a Law Masterplan. This will contain an array of proposed environmental improvements i.e. path & steps restoration and woodland management, and also enhancing the heritage of the site for the public to enjoy. If after reading this welcome pack you would like to join the Friends of Dundee Law or are interested in finding out more please contact Jen Thomson. Contact details can be found on the back page of this pack . !n introduction to the Dundee Law The Dundee Law is a popular urban green space and prominent feature on the Dundee skyline. There is approximately 8.25ha of woodland with additional areas of open ground which greatly contribute in providing wildlife habitat and recreational opportunities. -

Orcadian Basin Devonian Extensional Tectonics Versus Carboniferous

Journal of the Geological Society Devonian extensional tectonics versus Carboniferous inversion in the northern Orcadian basin M. SERANNE Journal of the Geological Society 1992; v. 149; p. 27-37 doi:10.1144/gsjgs.149.1.0027 Email alerting click here to receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article service Permission click here to seek permission to re-use all or part of this article request Subscribe click here to subscribe to Journal of the Geological Society or the Lyell Collection Notes Downloaded by INIST - CNRS trial access valid until 31/05/2008 on 31 March 2008 © 1992 Geological Society of London Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 149, 1992, pp. 21-31, 14 figs, Printed in Northern Ireland Devonian extensional tectonics versus Carboniferous inversion in the northern Orcadian basin M. SERANNE Laboratoire de Gdologie des Bassins, CNRS u.a.1371, 34095 Montpellier cedex 05, France Abstract: The Old Red Sandstone (Middle Devonian) Orcadian basin was formed as a consequence of extensional collapse of the Caledonian orogen. Onshore study of these collapse-basins in Orkney and Shetland provides directions of extension during basin development. The origin of folding of Old Red Sandstone sediments, that has generally been related to a Carboniferous inversion phase, is discussed: syndepositional deformation supports a Devonian age and consequently some of the folds are related to basin formation. Large-scale folding of Devonian strata results from extensional and left-lateral transcurrent faulting of the underlying basement. Spatial variation of extension direction and distribution of extensional and transcurrent tectonics fit with a model of regional releasing overstep within a left- lateral megashear in NW Europe during late-Caledonian extensional collapse. -

Angus, Scotland Fiche and Film

Angus Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1841 Census Index 1891 Census Index Parish Registers 1851 Census Directories Probate Records 1861 Census Maps Sasine Records 1861 Census Indexes Monumental Inscriptions Taxes 1881 Census Transcript & Index Non-Conformist Records Wills 1841 CENSUS INDEXES Index to the County of Angus including the Burgh of Dundee Fiche ANS 1C-4C 1851 CENSUS Angus Parishes in the 1851 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Parish of Auchterhouse (273) East Scotson Greenford Balbuchly Mid-Lioch East Lioch West Lioch Upper Templeton Lower Templeton Kirkton BonninGton Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Whitefauld East Mains Burnhead Gateside Newton West Mains Eastfields East Adamston Bronley Parish of Barry (274) Film 1851 Census ANS1 Parish of Brechin (275) Little Brechin Trinity Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Royal Burgh of Brechin Brechin Lock-Up House for the City of Brechin Brechin Jail Parish of Carmyllie (276) CarneGie Stichen Mosside Faulds Graystone Goat Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Dislyawn Milton Redford Milton of Conan Dunning Parish of Montrose (312) Film 1851 Census ANS 2 1861 CENSUS Angus Parishes in the 1861 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Parish of Aberlemno (269) Film ANS 269-273 Parish of Airlie (270) Film ANS 269-273 Parish of Arbirlot (271) Film ANS 269-273 Updated 18 August 2018 Page 1 of 12 Angus Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1861 CENSUS Continued Parish of Abroath (272) Parliamentary Burgh of Abroath Abroath Quoad Sacra Parish of Alley - Arbroath St. -

Kinnettles Kist

Kinnettles Kist Published by Kinnettles Heritage Group Printed by Angus Council Print & Design Unit. Tel: 01307 473551 © Kinnettles Heritage Group. First published March 2000. Reprint 2006. Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 - A Brief Geography Lesson 2 Chapter 2 - The Kerbet and its Valley 4 Chapter 3 - The Kirk and its Ministers 17 Chapter 4 - Mansion Houses and Estates 23 Chapter 5 - Interesting Characters in Kinnettles History 30 Chapter 6 - Rural Reminiscences 36 Chapter 7 - Kinnettles Schools 49 Chapter 8 - Kinnettles Crack 62 Chapter 9 - Farming, Frolics and Fun 74 Chapter 10 - The 1999 survey 86 Acknowledgements 99 Bibliography 101 Colour Plates : People and Places around Kinnettles i - xii Introduction Kinnettles features in all three Statistical Accounts since 1793. These accounts were written by the ministers of the time and, together with snippets from other books such as Alex Warden’s “Angus or Forfarshire – The Land and People”, form the core of our knowledge of the Parish’s past. In the last 50 years the Parish and its people have undergone many rapid and significant changes. These have come about through local government reorganisations, easier forms of personal transport and the advent of electricity, but above all, by the massive changes in farming. Dwellings, which were once farmhouses or cottages for farm-workers, have been sold and extensively altered. New houses have been built and manses, and even mansion houses, have been converted to new uses. What used to be a predominantly agricultural community has now changed forever. The last full Statistical Account was published in 1951, with revisions in 1967.