Res Judicata and Collateral Estoppel Issues in Class Litigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Meritorious Summary Judgment Motions

Examples of meritorious summary judgment motions By: Douglas H. Wilkins and Daniel I. Small February 13, 2020 Our last two columns addressed the real problem of overuse of summary judgment. Underuse is vanishingly rare. Even rarer (perhaps non-existent) is the case in which underuse ends up making a difference in the long run. But there are lessons to be learned by identifying cases in which you really should move for summary judgment. It is important to provide a reference point for evaluating the wisdom of filing a summary judgment motion. Here are some non-exclusive examples of good summary judgment candidates. Unambiguous written document: Perhaps the most common subject matter for a successful summary judgment motion is the contracts case or collections matter in which the whole dispute turns upon the unambiguous terms of a written note, contract, lease, insurance policy, trust or other document. See, e.g. United States Trust Co. of New York v. Herriott, 10 Mass. App. Ct. 131 (1980). The courts have said, quite generally, that “interpretation of the meaning of a term in a contract” is a question of law for the court. EventMonitor, Inc. v. Leness, 473 Mass. 540, 549 (2016). That doesn’t mean all questions of contract interpretation — just the unambiguous language. When the language of a contract is ambiguous, it is for the fact-finder to ascertain and give effect to the intention of the parties. See Acushnet Company v. Beam, Inc., 92 Mass. App. Ct. 687, 697 (2018). Ambiguous contracts are therefore not fodder for summary judgment. Ironically, there may be some confusion about what “unambiguous” means. -

The Doctrine of Clean Hands

LITIGATION - CANADA AUTHORS "Clean up, clean up, everybody clean up": the Norm Emblem doctrine of clean hands December 06 2016 | Contributed by Dentons Introduction Origins Bethany McKoy Recent cases Comment Introduction On occasion, in response to a motion or claim by an adverse party seeking equitable relief, a party will argue that the relief sought should be denied on the basis that the moving party has not come to court with 'clean hands'. This update traces the origin of what is often referred to as the 'doctrine of clean hands' and examines recent cases where: l a moving party has been denied equitable relief on the basis that it came to court with unclean hands; and l such arguments did not defeat the moving party's claim. Origins The doctrine of clean hands originated in the English courts of chancery as a limit to a party's right to equitable relief, where the party had acted inequitably in respect of the matter. In the seminal case Toronto (City) v Polai,(1) the Ontario Court of Appeal provided some insight into the origins and purpose of the doctrine: "The maxim 'he who comes into equity must come with clean hands' which has been invoked mostly in cases between private litigants, requires a plaintiff seeking equitable relief to show that his past record in the transaction is clean: Overton v. Banister (1844), 3 Hare 503, 67 E.R. 479; Nail v. Punter (1832), 5 Sim. 555, 58 E.R. 447; Re Lush's Trust (1869), L.R. 4 Ch. App. 591. These cases present instances of the Court's refusal to grant relief to the plaintiff because of his wrongful conduct in the very matter which was the subject of the suit in equity."(2) Although the court declined to use the doctrine to dismiss the appellant's action for an injunction in that case, it did set the stage for the maxim's future use in Canadian courts. -

Trial Process in Virginia

te Trial Process In Virginia A Litigation Boutique THE TRIAL PROCESS IN VIRGINIA table of contents Overview . .3 Significant .MOtiOnS .in .virginia . .4 . Plea .in .Bar . .4 . DeMurrer. .5 . craving .Oyer . .5 Voir .Dire . anD .Jury .SelectiOn .in .virginia . .6 OPening .StateMent . .8 the .receiPt .Of .e viDence . .10 MOtiOnS .tO .Strike . the .eviDence . .12 crOSS-exaMinatiOn . .14 clOSing .arguMent. .15 Jury .inStructiOnS . .17 Making .a .recOrD .fOr .aPP eal . .17 tiMe .liMitS .fOr .nO ting .anD .Perfecting . an .aPPeal . .18 key .tiMe .liMit S .fOr . the .SuPreMe .cOurt .Of .virginia . .19 THE TRIAL PROCESS IN VIRGINIA overview The trial of a civil case in Virginia takes most of its central features from the English court system that was introduced into the “Virginia Colony” in the early 1600s. The core principles of confrontation, the right to a trial by one’s peers, hearsay principles and many other doctrines had already been originated, extensively debated and refined in English courts and Inns of Court long before the first gavel fell in a Virginia case. It is clearly a privilege to practice law in the historically important court system of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and everyone who “passes the bar” and earns the right to sit inside the well of the court literally follows in the footsteps of such groundbreaking pioneers as Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, George Wythe, John Marshall, Lewis Powell and Oliver Hill. However, this booklet is not designed to address either the history or the policy of the law, or to discuss the contributions of these and other legal giants whose legacy is the living system that we enjoy today as professional attorneys. -

The Analysis and Decision of Summary Judgment Motions· a Monograph on Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. The Analysis and Decision of Summary Judgment Motions· A Monograph on Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure \f1 (»" It Judicial Center ~ ~ The Federal Judicial Center Board The Chief Justice of the United States, Chairman Judge Edward R. Becker U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Judge Martin L. C. Feldman U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana Judge Diana E. Murphy U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota Judge David D. Dowd, Jr. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio Judge Sidney B. Brooks U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Colorado Honorable 1. Ralph Mecham Director of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts Director Judge William W Schwarzer Deputy Director Russell R. Wheeler Division Directors Steven A. Wolvek, Court Education Division Denis J. Hauptly, Judicial Education Division Sylvan A. Sobel, Publications & Media Division William B. Eldridge, Research Division Federal Judicial Center, 1520 H Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20005 1 ~•. ~ .. ~:' i ' NCJRS· MAR 4 199? ACQUISITIONS The Analysis and Decision of Summary Judgment Motions A Monograph on Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure William W Schwarzer Alan Hirsch David J. Barrans Federal Judicial Center 1991 This publication was produced in furtherance of the Center's statutory mis sion to conduct and stimulate research and development on matters of judi cial administration. The statements, conclusions, and points of view are those of the authors. -

What Is a Summary Judgment Motion? Notice for Parties Who Do Not Have a Lawyer

What is a Summary Judgment Motion? Notice for Parties Who Do Not Have a Lawyer A summary judgment motion was filed in your case. A summary judgment motion asks the court to decide this case without having a trial. Here are some important things to know. What is summary judgment? Summary judgment is a way for one party to win their case without a trial. The party can ask for summary judgment for part of the case or for the whole case. What happens if I ignore the motion? If you do not respond to the summary judgment motion, you can lose your case without the judge hearing from you. If you are the plaintiff or petitioner in the case, that means that your case can be dismissed. If you are the defendant or respondent, that means the plaintiff or petitioner can get everything they asked for in the complaint. How do I respond to a summary judgment motion? You can file a brief and tell the judge about the law and the facts that support your side of the case. A brief is not evidence and the facts that you write about in your brief need to be supported by evidence. You can file sworn affidavits, declarations, and other paperwork to support your case. An affidavit or declaration is a sworn statement of fact that is based on personal knowledge and is admissible as evidence. If you are a plaintiff or petitioner, you cannot win a summary judgment motion just by saying what is in your complaint. Instead, you need to give evidence such as affidavits or declarations. -

Reconsidering Res Judicata: a Comparative Perspective

SINAI_PROOF2 3/25/2011 1:53:37 PM RECONSIDERING RES JUDICATA: A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE YUVAL SINAI* “Res judicata changes white to black and black to white, it makes the crooked straight and the straight crooked.”1 INTRODUCTION Final judgments create legal barriers to relitigation. These barriers are the rules of res judicata (“RJ”), which means “a matter that has been adjudicated.”2 The term res judicata refers to the various ways in which one judgment exercises a binding effect on another. The rules of RJ have undergone a significant change in scope.3 In the old common law, its scope was quite narrow. A judgment entered in a case on one form of action did not prevent litigants from pursuing another form of action, although only one recovery was permitted for a single loss.4 With changes in the rules of litigation as part of the evolution of modern procedure, the scope of the rules of RJ is wider. The basic proposition of RJ, however, has remained the same: a party should not be allowed to relitigate a matter that it has already litigated.5 As the modern rules of procedure have expanded the scope of the initial opportunity to litigate, they have correspondingly limited subsequent opportunities to litigate a subsequent one.6 As we shall see, this is the clear tendency in the modern law of RJ. * Ph.D; L.L.B; Senior Lecturer of Civil Procedure and Jewish Law, Director of the Center for the Application of Jewish Law (ISMA), Law School, Netanya Academic College, and also teaches in the Law Faculty of Bar-Ilan University (Israel); Visiting Professor at McGill University, Canada (2007- 2008). -

The Restitution Revival and the Ghosts of Equity

The Restitution Revival and the Ghosts of Equity Caprice L. Roberts∗ Abstract A restitution revival is underway. Restitution and unjust enrichment theory, born in the United States, fell out of favor here while surging in Commonwealth countries and beyond. The American Law Institute’s (ALI) Restatement (Third) of Restitution & Unjust Enrichment streamlines the law of unjust enrichment in a language the modern American lawyer can understand, but it may encounter unintended problems from the law-equity distinction. Restitution is often misinterpreted as always equitable given its focus on fairness. This blurs decision making on the constitutional right to a jury trial, which "preserves" the right to a jury in federal and state cases for "suits at common law" satisfying specified dollar amounts. Restitution originated in law, equity, and sometimes both. The Restatement notably attempts to untangle restitution from the law-equity labels, as well as natural justice roots. It explicitly eschews equity’s irreparable injury prerequisite, which historically commanded that no equitable remedy would lie if an adequate legal remedy existed. Can restitution law resist hearing equity’s call from the grave? Will it avoid the pitfalls of the Supreme Court’s recent injunction cases that return to historical, equitable principles and reanimate equity’s irreparable injury rule? Losing anachronistic, procedural remedy barriers is welcome, but ∗ Professor of Law, West Virginia University College of Law; Visiting Professor of Law, The Catholic University of America Columbus School of Law. Washington & Lee University School of Law, J.D.; Rhodes College, B.A. Sincere thanks to Catholic University for supporting this research and to the following conferences for opportunities to present this work: the American Association of Law Schools, the Sixth Annual International Conference on Contracts at Stetson University College of Law, and the Restitution Rollout Symposium at Washington and Lee University School of Law. -

Promissory Estoppel, the Civil Law, and the Mixed Jurisdiction

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 1998 Comparative Law in Action: Promissory Estoppel, the Civil Law, and the Mixed Jurisdiction David V. Snyder Indiana University School of Law - Bloomington Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Civil Law Commons, and the Contracts Commons Recommended Citation Snyder, David V., "Comparative Law in Action: Promissory Estoppel, the Civil Law, and the Mixed Jurisdiction" (1998). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 2297. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/2297 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARATIVE LAW IN ACTION: PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL, THE CIVIL LAW, AND THE MIXED JURISDICTION David V. Snyder* "Touching estoppels, which is an excellent and curious kind of learning. .. I. PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL IN A MIXED JURISDICTION Promissory estoppel, a quintessential creature of the common law, is ordinarily thought to be unknown to the civil law. Arising at first through a surreptitious undercurrent of American case law, promissory estoppel was eventually rationalized in the Restatement of Contracts (Restatement)2 as a necessary adjunct to the bargain theory of consideration. The civil law, with its flexible notion of causa or cause, is free from the constraints of the consideration doctrine. The civil law should not need promissory estoppel. At least initially, the common law and the civil law would appear as disparate in this area as anywhere, and comparative lawyers would be confined to observations about two systems that never meet. -

Estoppel in Property Law Stewart E

Nebraska Law Review Volume 77 | Issue 4 Article 8 1998 Estoppel in Property Law Stewart E. Sterk Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation Stewart E. Sterk, Estoppel in Property Law, 77 Neb. L. Rev. (1998) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol77/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Stewart E. Sterk* Estoppel in Property Law TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 756 II. Land Transfers ....................................... 759 A. Inadequate Writings .............................. 760 B. Oral "Agreements". ............................... 764 III. Servitudes by Estoppel ................................ 769 A. Representations by Sellers or Developers .......... 769 B. Representations by Neighbors ..................... 776 C. The Restatement .................................. 784 IV. Termination of Servitudes ............................. 784 V. Boundary Disputes .................................... 788 A. Estoppel Against a True Owner .................... 788 1. By the True Owner's Representations .......... 788 2. By Physical Barriers and Improvements Without Representations ............................... 791 B. Estoppel to Claim Adverse Possession -

Res Judicata As Requisite for Justice Kevin M

Cornell University Law School Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Spring 2016 Res Judicata as Requisite for Justice Kevin M. Clermont Cornell Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Kevin M. Clermont, "Res Judicata as Requisite for Justice," 68 Rutgers University Law Review (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RES JUDICATA As REQUISITE FOR JUSTICE Kevin M. Clermont* Abstract From historical,jurisprudential, and comparative perspectives, this Article tries to synthesize res judicata while integrating it with the rest of law. From near their beginnings, all systems of justice have delivered a core of res judicata comprising the substance of bar and defense preclusion. This core is universal not because it represents a universal value, but rather because it responds to a universal institutional need. Any justice system must have adjudicators; to be effective, their judgments must mean something with bindingness; and the minimal bindingness is that, except in specified circumstances, the disgruntled cannot undo a judgment in an effort to change the outcome. By some formulation of rules and exceptions, each justice system must and does deliver this core of res judicata. Fundamental fairness imposes some distant outer limit on res judicata, too. -

MARSHALLING SECURITIES and WORDS of RELEASE

MARSHALLING SECURITIES and WORDS OF RELEASE Note on Hill v Love (2018) 53 V.R. 459 and Burness v Hill [2019] VSCA 94 © D.G. Robertson, Q.C., B.A., LL.M., M.C.I.Arb. Queen’s Counsel Victorian Bar 205 William Street, Melbourne Ph: 9225 7666 | Fax: 9225 8450 www.howellslistbarristers.com.au [email protected] -2- Table of Contents 1. The Doctrine of Marshalling 3 2. The Facts in Hill v Love 5 2.1 Facts Relevant to Marshalling 5 2.2 Facts Relevant to the Words of Release Issue 6 3. The Right to Marshal 7 4. Limitations on and Justification of Marshalling 9 4.1 Principle 9 4.2 Arrangement as to Order of Realization of Securities 10 5. What is Secured by Marshalling? 11 5.1 Value of the Security Property 11 5.2 Liabilities at Time of Realization of Prior Security 12 5.3 Interest and Costs 14 6. Uncertainties in Marshalling 15 6.1 Nature of Marshalling Right 15 6.2 Caveatable Interest? 17 6.3 Proprietary Obligations 18 7. Construction of Words of Release 19 7.1 General Approach to the Construction of Contracts 19 7.2 Special Rules for the Construction of Releases 20 7.3 Grant v John Grant & Sons Pty. Ltd. 22 8. Other Points 24 8.1 Reasonable Security 24 8.2 Fiduciary Duty 24 8.3 Anshun Estoppel 25 This paper was presented on 18 September 2019 at the Law Institute of Victoria to the Commercial Litigation Specialist Study Group. Revised 4 December 2019. -3- MARSHALLING SECURITIES and WORDS OF RELEASE The decisions of the Supreme Court of Victoria in Hill v Love1 and, on appeal, Burness v Hill2 address the doctrine of marshalling securities and also the construction of words of release in terms of settlement. -

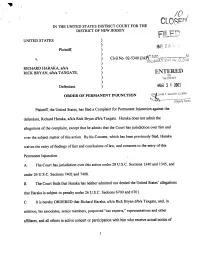

Order of Permanent Injunction

~ I() / ClOSFri IN TH UNTED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY ~ :-~:~~rx:: FI'l'. ,.¡lÕ '-- . ...'íF=~ ,::,.~-'--'f;~."' ._---, ,,~.-,.' UNTED STATES ) H ii ii,; l' C( r ) ~t'rA~~ c" C\ f Plaintiff ) ) v. Civil No. 02-5340 (JAti O:30_,_~~~!'~ ) \:ViUJMfi T. 'vLt::Rh ) RICHA HA a/a ) RICK BRYAN, d//a TAXGATE, ) ENTERED ON ) THE DOCKET ) Defendant. ) MAR 3 1 2003 ORDER OF PERMNENT INJUNCTION 8~!AM T....WALSH,Y .--CLERK " (Deputy Cierk) Plaintiff the United States, has filed a Complaint for Permanent Injunction against the defendant, Richard Haraka, aIa Rick Bryan d//a Taxgate. Haraka does not admit the allegations of the complaint, except that he admits that the Court has jurisdiction over him and over the subject matter of this action. By his Consent, which has been previously filed, Haraka law, and consents to the entry of waives the entry of findings offact and conclusions of this Permanent Injunction. A. The Court has jurisdiction over this action under 28 U.S.c. Sections 1340 and 1345, and under 26 U.S.C. Sections 7402 and 7408. B. The Court finds that Haraka has neither admitted nor denied the United States' allegations that Haraka is subject to penalty under 26 U.S.C. Sections 6700 and 6701. C. It is hereby ORDERED that Richard Haraka, a/a Rick Bryan d//a Taxgate, and, in addition, his associates, senior members, purported "tax experts," representatives and other affliates, and all others in active concert or participation with him who receive actual notice of i 1 .~ this Order, are permanently restrained and enjoined from directly or indirectly: 1.