Domino by Kathleen Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bold Example (Usa)

BOLD EXAMPLE (USA) Bold Ruler Nasrullah Sire: (Bay 1954) Miss Disco BOLD LAD (USA) (Chesnut 1962) Misty Morn Princequillo BOLD EXAMPLE (USA) (1952) Grey Flight (mare 1969) Better Self Bimelech Dam: (Bay 1945) Bee Mac LADY BE GOOD (1956) Past Eight Eight Thirty (Chesnut 1945) Helvetia 5Sx5S Blenheim II Bold Example (USA), won 3 races in U.S.A. at 2 and 3 years and £18,159, placed second in Blue Hen Stakes, Delaware Park and Polly Drummond Stakes, Delaware Park and fourth in Matron Stakes, Belmont Park, Gr.1, Selima Stakes, Laurel, Gr.1 and Seashore Stakes, Monmouth Park, Gr.3; Own sister to GOOD LAD (USA); dam of 5 winners: 1974 FRENCH CONNECTION (USA) (c. by Le Fabuleux), won 2 races in U.S.A. at 3 and 5 years and £6,674 and placed once. 1975 Up And Coming (USA) (f. by Pronto), died at 2. 1976 Past Example (USA) (f. by Buckpasser), unraced; dam of 3 winners. POLISH PRECEDENT (USA) (c. by Danzig (USA)), Top rated 3yr old miler in France in 1989, 4th top rated 3yr old in Europe in 1989, placed at 3 years and £56,800 second in Queen Elizabeth II Stakes, Ascot, Gr.1; also 7 races in France at 3 years and £261,578 including Prix du Moulin de Longchamp, Longchamp, Gr.1, P. Fresnay-le-Buffard Jacques Le Marois, Deauville, Gr.1, Prix de la Jonchere, Chantilly, Gr.3, Prix du Palais Royal, Longchamp, Gr.3, Prix Messidor, M'-Laffitte, Gr.3 and Prix du Pont-Neuf, Longchamp, L.; sire. -

Dutch Masters *§

C-4 •?•THE SUNDAY STAR, Washington, D. C. THINGS MUCH MORE SIMPLE THEN SUNDAY, AUGUST SS, 1985 Thane of Wales' iFarmer Takes Forest1 Witch Domino Ran Dead Heats Doubles Title Races Sweeps Class In Trapshoot Wins in Upset In 2 of 3 Match ! VANDALIA, Ohio, Aug. 27 • t Continued from Page C-l Star1 account simply states that .UP).— Hugh McKinley. 40-year- it resulted in a dead heat, with;AI Gaithersburg old farmer from Harrisburg, Haymarkel Futurity At praised Domino highly allj bets declared off and no run- Ohio, today won the national —end Jockey Fred Taral extrava- ( Racing By BRUCE FALEB, JR. championship at By ROBERT B. PHILLIPS winning off. The American doubles the gantly-i-for with 130, Manual's records on Domino add I Special Correipondent of The Star Grand American Trapshoot with Special Correspondent ofThe Star up after half-hour post pounds a little,j except that the Keenes’ Nancy Gorrell rode her vet- a score of 97 of 100. HAYMARKET,Va.. Aug. 27. delay. also pointed out that | It json of Himyar was the l-to-2 gray gelding Thane of collided , -1 eran In the doubles event—nearest Forest Witch, a big chestnut at the start Dobbins favorite and the race was run a sweep thing Hyderrabad, Domino’s sta- 1 Wales to clean in the : to bird shooting in the mare, turned up the surprise with inj 1:12%. points targets as blemate, violently that Over- three classes for 15 and field—two are thrown so • colts went on to greater, .the small pony championship in simultaneously a 40-degree ! conformation hunter champion ton, Hyderabad’s rider, Both at was' things 3-year-olds in a Montgomery County angle. -

EDITED PEDIGREE for SHARIN (GER)

EDITED PEDIGREE for SHARIN (GER) Big Shuffle (USA) Super Concorde (USA) Sire: (Bay 1984) Raise Your Skirts (USA) AREION (GER) (Bay 1995) Aerleona (IRE) Caerleon (USA) SHARIN (GER) (Chesnut 1988) Alata (Bay mare 2011) King's Theatre (IRE) Sadler's Wells (USA) Dam: (Bay 1991) Regal Beauty (USA) SISIKA (IRE) (Bay 2004) Sistadari (GB) Shardari (Bay 1988) Sistabelle 5Sx4D Northern Dancer, 5Sx5D Raise A Native Sharin (GER), won 3 races in Germany at 2 and 3 years and £11,565, placed 3 times including third in Kolner Zweijahrigen Trophy, Cologne, L. ; dam of 1 winner: 2016 Sharoka (IRE) (f. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), won 3 races in Germany at 2 and 3 years, 2019 and £28,583, placed 3 times including second in Henkel Stutenpreis, Dusseldorf, L. and Racebets Winterkonigin Trial, Dusseldorf, L. 2017 Sean (GER) (c. by Excelebration (IRE)), placed once in Germany at 2 years, 2019. 1st Dam SISIKA (IRE), unraced; dam of 2 winners: Sharin (GER), see above. SO PROUD (GER) (2013 f. by Sir Percy (GB)), won 3 races in France and Germany from 3 to 5 years, 2018 and £29,935 and placed 12 times. Selda (GER) (2010 f. by Desert Prince (IRE)), placed twice in Germany at 3 years. Schnucki (GER) (2016 f. by Reliable Man (GB)), placed twice in Germany at 2 years, 2018 and £1,593. Sings My Soul (GER) (2017 c. by Reliable Man (GB)), ran once in Germany at 2 years, 2019. 2nd Dam SISTADARI (GB), placed 4 times at 3 years; dam of 5 winners: SIMONAS (IRE) (c. -

Juddmonte-Stallion-Brochure-2021

06 Celebrating 40 years of Juddmonte by David Walsh 32 Bated Breath 2007 b h Dansili - Tantina (Distant View) The best value sire in Europe by blacktype performers in 2020 36 Expert Eye 2015 b h Acclamation - Exemplify (Dansili) A top-class 2YO and Breeders’ Cup Mile champion 40 Frankel 2008 b h Galileo - Kind (Danehill) The fastest to sire 40 Group winners in history 44 Kingman 2011 b h Invincible Spirit - Zenda (Zamindar) The Classic winning miler siring Classic winning milers 48 Oasis Dream 2000 b h Green Desert - Hope (Dancing Brave) The proven source of Group 1 speed WELCOME his year, the 40th anniversary of the impact of the stallion rosters on the Green racehorses in each generation. But we also Juddmonte, provides an opportunity to Book is similarly vital. It is very much a family know that the future is never exactly the same Treflect on the achievements of Prince affair with our stallions being homebred to as the past. Khalid bin Abdullah and what lies behind his at least two generations and, in the case of enduring and consistent success. Expert Eye and Bated Breath, four generations. Juddmonte has never been shy of change, Homebred stallions have been responsible for balancing the long-term approach, essential Prince Khalid’s interest in racing goes back to over one-third of Juddmonte’s 113 homebred to achieving a settled and balanced breeding the 1950s. He first became an owner in the Gr.1 winners. programme, with the sometimes difficult mid-1970s and, in 1979, won his first Group 1 decisions that need to be made to ensure an victory with Known Fact in the Middle Park Juddmonte’s activities embrace every stage in effective operation, whilst still competing at Stakes at Newmarket and purchased his first the life of a racehorse from birth to training, the highest level. -

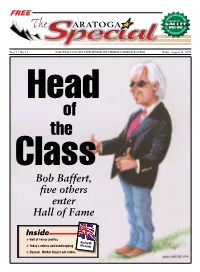

Bob Baffert, Five Others Enter Hall of Fame

FREE SUBSCR ER IPT IN IO A N R S T COMPLIMENTS OF T !2!4/'! O L T IA H C E E 4HE S SP ARATOGA Year 9 • No. 15 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Friday, August 14, 2009 Head of the Class Bob Baffert, five others enter Hall of Fame Inside F Hall of Famer profiles Racing UK F Today’s entries and handicapping PPs Inside F Dynaski, Mother Russia win stakes DON’T BOTHER CHECKING THE PHOTO, THE WINNER IS ALWAYS THE SAME. YOU WIN. You win because that it generates maximum you love explosive excitement. revenue for all stakeholders— You win because AEG’s proposal including you. AEG’s proposal to upgrade Aqueduct into a puts money in your pocket world-class destination ensuress faster than any other bidder, tremendous benefits for you, thee ensuring the future of thorough- New York Racing Associationn bred racing right here at home. (NYRA), and New York Horsemen, Breeders, and racing fans. THOROUGHBRED RACING MUSEUM. AEG’s Aqueduct Gaming and Entertainment Facility will have AEG’s proposal includes a Thoroughbred Horse Racing a dazzling array Museum that will highlight and inform patrons of the of activities for VLT REVENUE wonderful history of gaming, dining, VLT OPERATION the sport here in % retail, and enter- 30 New York. tainment which LOTTERY % AEG The proposed Aqueduct complex will serve as a 10 will bring New world-class gaming and entertainment destination. DELIVERS. Yorkers and visitors from the Tri-State area and beyond back RACING % % AEG is well- SUPPORT 16 44 time and time again for more fun and excitement. -

Pedigree Evaluation PICK of the BUNCH Suitable Mares for Iesque’S Approval (USA) Miesque’S Approval Could Include 1

Karel Miedema’s Pedigree Evaluation PICK OF THE BUNCH Suitable mares for iesque’s Approval (USA) Miesque’s Approval could include 1. Mares with La Troienne duplications, Miesque’s Son - Win Approval by With Approval notably Seattle Slew (AP Indy) M 2. Mares with Buckpasser (Al Mufti) or others from his affinity group, incl “Anything that has worked so well for Nijinsky (Dancing Champ), Blushing a century is not apt to suddenly stop Groom, Dinner Partner (Caesour), etc. 3. Mares with Hoist The Flag (Alleged, working - the gene pool cannot react Sportsworld (!), Joshua Dancer, that fast,” Ginistrelli, etc.) 4. Mares with Tourbillon/Count Fleet (Mr P., -Kentucky pedigree analyst Les Brinsfield Never Bend/Mill Reef/Bold Reason) 5. Mares with Gold Bridge, notably the ○○○○○○○ Rough Shod female line (Sadler’s Wells, Brinsfield refers to the art of predicting successful broodmare sires. His focal point is Nureyev, Golden Thatch, Lt Stevens, how the remarkable sire Domino and his daughters have shaped history. It goes like notably Houston Connection) this. 6. Mares with Hail To Reason (Bold Reason, Domino mares produced stallion sons Ultimus, High Tiem and Sweep. Roberto, etc) Ultimus is the damsire of Case Ace (damsire of Raise a Native) and second 7. Mares with Gulf Stream (Soho Secret, damsire of Roman. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ London News) High Time is the damsire of Eight Thirty. 8. Mares with male lines of Sweep, as in Sweep is the damsire of Bubbling Over and War Admiral. Bold Ruler (notably Jungle Cove), Best Turn (Best By Test) Now follow the latter tribe. War Admiral got Mr Busher from Bubbling Over mare Baby League, as well as full sisters Striking and Busher. -

Investing in Thoroughbreds the Journey

Investing in Thoroughbreds The Journey Owning world-class Thoroughbred race horses is one of the gree credentials, McPeek continually ferrets out not only most exciting endeavors in the world. A fast horse can take people on value but future stars at lower price points. McPeek selected the journey of a lifetime as its career unfolds with the elements of a the yearling Curlin at auction for $57,000, and the colt went great storybook – mystery, drama, adventure, fantasy, romance. on to twice be named Horse of the Year and earn more than $10.5 million. While purchasing horses privately and at major Each race horse is its own individual sports franchise, and the right U.S. auctions, McPeek also has enhanced his credentials by one can venture into worlds once only imagined: the thrilling spotlight finding top runners at sales in Brazil and Argentina. of the Kentucky Derby, Preakness and Belmont Stakes, or to the gathering of champions at the Breeders’ Cup. The right one can lead As a trainer, McPeek has saddled horses in some of the to the historic beauty of Saratoga biggest events in the world, including the Kentucky Derby, Race Course, the horse heaven Breeders’ Cup, Preakness, and Belmont Stakes. Among the called Keeneland or under “Kenny has a unique eye nearly 100 Graded Stakes races that McPeek has won is the the famed twin spires at for Thoroughbred racing talent. He is a 2002 Belmont Stakes with Sarava. More recently in 2020, he Churchill Downs. campaigned the Eclipse Award Winning filly, Swiss Skydiver, superb developer of early racing potential and to triumph in the Preakness. -

TAILORMADE PEDIGREE for ECRIVAIN (FR)

TAILORMADE PEDIGREE for ECRIVAIN (FR) Shamardal (USA) Giant's Causeway (USA) Sire: (Bay 2002) Helsinki (GB) LOPE DE VEGA (IRE) (Chesnut 2007) Lady Vettori (GB) Vettori (IRE) ECRIVAIN (FR) (Bay 1997) Lady Golconda (FR) (colt 2017) Danehill Dancer (IRE) Danehill (USA) Dam: (Bay 1993) Mira Adonde (USA) SAPPHIRE PENDANT (IRE) (Bay 2008) Butterfly Blue (IRE) Sadler's Wells (USA) (Bay 2000) Blush With Pride (USA) 4Sx4S Machiavellian (USA), 5Sx5S Mr Prospector (USA), 5Sx5S Coup de Folie (USA), 6Sx5Dx4D Northern Dancer, 6Sx4D Blushing Groom (FR), 6Sx6S Raise A Native, 6Sx6S Gold Digger (USA), 6Sx6S Halo (USA), 6Sx6S Raise The Standard (CAN), 6Sx4D Sharpen Up, 6Dx5D Nearctic, 6Dx6Dx5D Natalma, 6Dx6D Native Dancer Last 5 starts 30/05/2021 upl PRIX D'ISPAHAN (Group 1) Parislongchamp 9f 55y 02/05/2021 upl PRIX GANAY (Group 1) Parislongchamp 10f 110y £7,661 11/04/2021 upl PRIX D'HARCOURT (Group 2) Parislongchamp 10f £8,125 21/03/2021 3rd PRIX EXBURY (Group 3) Saint-Cloud 10f £10,714 16/02/2021 1st PRIX DE LA PREMIERE ROUTE RONDE Chantilly 9f 110y £8,036 ECRIVAIN (FR), (FR 110), won 3 races (8f.-9f.) in France at 2 and 4 years, 2021 and £123,379 including Prix des Chenes, Parislongchamp, Gr.3, placed 4 times including second in Prix de Fontainebleau, Longchamp, Gr.3 and Prix Le Fabuleux, Chantilly, L. and third in Prix Exbury, Saint-Cloud, Gr.3. 1st Dam Sapphire Pendant (IRE) (2008 f. by Danehill Dancer (IRE)), €300,000 yearling Arqana Deauville August Yearlings 2009 - D L O'Byrne, 480,000 gns. mare Tattersalls December Mares 2012 - Wertheimer & Frere, (IRE 98), won 1 race (8f.) at 3 years and £18,565, placed second in Derrinstown Stud 1000 Guineas Trial, Leopardstown, Gr.3; Own sister to King George River (IRE); dam of 4 winners, 4 runners and 5 foals of racing age: ECRIVAIN (FR), see above. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Preakness Stakes .Fifty-Three Fillies Have Competed in the Preakness with Start in 1873: Rfive Crossing the Line First The

THE PREAKNESS Table of Contents (Preakness Section) History . .P-3 All-Time Starters . P-31. Owners . P-41 Trainers . P-45 Jockeys . P-55 Preakness Charts . P-63. Triple Crown . P-91. PREAKNESS HISTORY PREAKNESS FACTS & FIGURES RIDING & SADDLING: WOMEN & THE MIDDLE JEWEL: wo people have ridden and sad- dled Preakness winners . Louis J . RIDERS: Schaefer won the 1929 Preakness Patricia Cooksey 1985 Tajawa 6th T Andrea Seefeldt 1994 Looming 7th aboard Dr . Freeland and in 1939, ten years later saddled Challedon to victory . Rosie Napravnik 2013 Mylute 3rd John Longden duplicated the feat, win- TRAINERS: ning the 1943 Preakness astride Count Judy Johnson 1968 Sir Beau 7th Fleet and saddling Majestic Prince, the Judith Zouck 1980 Samoyed 6th victor in 1969 . Nancy Heil 1990 Fighting Notion 5th Shelly Riley 1992 Casual Lies 3rd AFRICAN-AMERICAN Dean Gaudet 1992 Speakerphone 14th RIDERS: Penny Lewis 1993 Hegar 9th Cynthia Reese 1996 In Contention 6th even African-American riders have Jean Rofe 1998 Silver’s Prospect 10th had Preakness mounts, including Jennifer Pederson 2001 Griffinite 5th two who visited the winners’ circle . S 2003 New York Hero 6th George “Spider” Anderson won the 1889 Preakness aboard Buddhist .Willie Simms 2004 Song of the Sword 9th had two mounts, including a victory in Nancy Alberts 2002 Magic Weisner 2nd the 1898 Preakness with Sly Fox “Pike”. Lisa Lewis 2003 Kissin Saint 10th Barnes was second with Philosophy in Kristin Mulhall 2004 Imperialism 5th 1890, while the third and fourth place Linda Albert 2004 Water Cannon 10th finishers in the 1896 Preakness were Kathy Ritvo 2011 Mucho Macho Man 6th ridden by African-Americans (Alonzo Clayton—3rd with Intermission & Tony Note: Penny Lewis is the mother of Lisa Lewis Hamilton—4th on Cassette) .The final two to ride in the middle jewel are Wayne Barnett (Sparrowvon, 8th in 1985) and MARYLAND MY Kevin Krigger (Goldencents, 5th in 2013) . -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

CHEETAH (URU) Br

CHEETAH (URU) br. F, 2009 DP = 6-1-10-1-0 (18) DI = 2.00 CD = 0.67 - GSV = 61.28 NORTHERN br. 1954 STORM BIRD NEARCTIC (CAN) 14-c DANCER (CAN) (CAN) b. 1957 b. 1978 (71.05) NATALMA (USA) 2-d b. 1961 [BC] (89.58) * 6-5-0-0 $168,891 NEW 699 f, 530 r, 377 w, SOUTH OCEAN (CAN) PROVIDENCE b. 1956 9-d STORM CAT 62 SW * (CAN) b. 1967 SHINING SUN (USA) AEI 2.26 b. 1962 4-j br. 1983 (71.93) (CAN) 8-4-3-0 BOLD RULER br. 1954 8-d $570,610 SECRETARIAT (USA) (USA) [BI] TERLINGUA (USA) SOMETHINGROYAL b. 1952 ch. 1970 [IC] (70.91) 2-s (USA) ch. 1976 * CRIMSON SATAN ch. 1959 17-7-4-1 CRIMSON SAINT 26 $423,896 (USA) THE LEOPARD (USA) * BOLERO ROSE ch. 1958 (USA) ch. 1969 8-c dkb/br. 2005 (USA) (27) MR. PROSPECTOR NATIVE DANCER gr. 1950 RAISE A NATIVE 5-f 6-3-1-0 (USA) (USA) [IC] (USA) $173,700 b. 1970 [BC] ch. 1946 (78.54) ch. 1961 [B] (66.19) RAISE YOU (USA) 8-f * 14-7-4-2 $112,171 b. 1952 GOLD DIGGER (USA) NASHUA (USA) 3-m 1195 f, 986 r, 755 [IC] MOON SAFARI w, 182 SW b. 1962 (USA) AEI 3.92 SEQUENCE (USA) b. 1946 13-c dkb/br. 1999 NORTHERN b. 1961 7-1-1-2 2-d NIJINSKY (CAN) DANCER (CAN) [BC] $29,389 FLAMING PAGE b. 1959 VIDEO (USA) b. 1967 [CS] (83.96) 8-f b.