Rotation Periods of Irregular Satellites of Saturn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Masers in the Saturnian System

A&A 494, L1–L4 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:200811186 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor Water masers in the Saturnian system S. V. Pogrebenko1,L.I.Gurvits1, M. Elitzur2,C.B.Cosmovici3,I.M.Avruch1,4, S. Montebugnoli5 , E. Salerno5, S. Pluchino3,5, G. Maccaferri5, A. Mujunen6, J. Ritakari6, J. Wagner6,G.Molera6, and M. Uunila6 1 Joint Institute for VLBI in Europe, PO Box 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands e-mail: [pogrebenko;lgurvits]@jive.nl 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Kentucky, 600 Rose Street, Lexington, KY 40506-0055, USA e-mail: [email protected] 3 Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF) – Istituto di Fisica dello Spazio Interplanetario (IFSI), via del Fosso del Cavaliere, 00133 Rome, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 4 Science & Technology BV, PO 608 2600 AP Delft, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 5 Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF) – Istituto di Radioastronomia (IRA) – Stazione Radioastronomica di Medicina, via Fiorentina 3508/B, 40059 Medicina (BO), Italy e-mail: [s.montebugnoli;e.salerno;g.maccaferri]@ira.inaf.it; [email protected] 6 Helsinki University of Technology TKK, Metsähovi Radio Observatory, 02540 Kylmälä, Finland e-mail: [amn;jr;jwagner;gofrito;minttu]@kurp.hut.fi Received 18 October 2008 / Accepted 4 December 2008 ABSTRACT Context. The presence of water has long been seen as a key condition for life in planetary environments. The Cassini spacecraft discovered water vapour in the Saturnian system by detecting absorption of UV emission from a background star. Investigating other possible manifestations of water is essential, one of which, provided physical conditions are suitable, is maser emission. -

Cassini Update

Cassini Update Dr. Linda Spilker Cassini Project Scientist Outer Planets Assessment Group 22 February 2017 Sols%ce Mission Inclina%on Profile equator Saturn wrt Inclination 22 February 2017 LJS-3 Year 3 Key Flybys Since Aug. 2016 OPAG T124 – Titan flyby (1584 km) • November 13, 2016 • LAST Radio Science flyby • One of only two (cf. T106) ideal bistatic observations capturing Titan’s Northern Seas • First and only bistatic observation of Punga Mare • Western Kraken Mare not explored by RSS before T125 – Titan flyby (3158 km) • November 29, 2016 • LAST Optical Remote Sensing targeted flyby • VIMS high-resolution map of the North Pole looking for variations at and around the seas and lakes. • CIRS last opportunity for vertical profile determination of gases (e.g. water, aerosols) • UVIS limb viewing opportunity at the highest spatial resolution available outside of occultations 22 February 2017 4 Interior of Hexagon Turning “Less Blue” • Bluish to golden haze results from increased production of photochemical hazes as north pole approaches summer solstice. • Hexagon acts as a barrier that prevents haze particles outside hexagon from migrating inward. • 5 Refracting Atmosphere Saturn's• 22unlit February rings appear 2017 to bend as they pass behind the planet’s darkened limb due• 6 to refraction by Saturn's upper atmosphere. (Resolution 5 km/pixel) Dione Harbors A Subsurface Ocean Researchers at the Royal Observatory of Belgium reanalyzed Cassini RSS gravity data• 7 of Dione and predict a crust 100 km thick with a global ocean 10’s of km deep. Titan’s Summer Clouds Pose a Mystery Why would clouds on Titan be visible in VIMS images, but not in ISS images? ISS ISS VIMS High, thin cirrus clouds that are optically thicker than Titan’s atmospheric haze at longer VIMS wavelengths,• 22 February but optically 2017 thinner than the haze at shorter ISS wavelengths, could be• 8 detected by VIMS while simultaneously lost in the haze to ISS. -

A Deeper Look at the Colors of the Saturnian Irregular Satellites Arxiv

A deeper look at the colors of the Saturnian irregular satellites Tommy Grav Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, MS51, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA02138 and Instiute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Dr., Honolulu, HI86822 [email protected] James Bauer Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology 4800 Oak Grove Dr., MS183-501, Pasadena, CA91109 [email protected] September 13, 2018 arXiv:astro-ph/0611590v2 8 Mar 2007 Manuscript: 36 pages, with 11 figures and 5 tables. 1 Proposed running head: Colors of Saturnian irregular satellites Corresponding author: Tommy Grav MS51, 60 Garden St. Cambridge, MA02138 USA Phone: (617) 384-7689 Fax: (617) 495-7093 Email: [email protected] 2 Abstract We have performed broadband color photometry of the twelve brightest irregular satellites of Saturn with the goal of understanding their surface composition, as well as their physical relationship. We find that the satellites have a wide variety of different surface colors, from the negative spectral slopes of the two retrograde satellites S IX Phoebe (S0 = −2:5 ± 0:4) and S XXV Mundilfari (S0 = −5:0 ± 1:9) to the fairly red slope of S XXII Ijiraq (S0 = 19:5 ± 0:9). We further find that there exist a correlation between dynamical families and spectral slope, with the prograde clusters, the Gallic and Inuit, showing tight clustering in colors among most of their members. The retrograde objects are dynamically and physically more dispersed, but some internal structure is apparent. Keywords: Irregular satellites; Photometry, Satellites, Surfaces; Saturn, Satellites. 3 1 Introduction The satellites of Saturn can be divided into two distinct groups, the regular and irregular, based on their orbital characteristics. -

Search for Rings and Satellites Around the Exoplanet Corot-9B Using Spitzer Photometry A

Search for rings and satellites around the exoplanet CoRoT-9b using Spitzer photometry A. Lecavelier Etangs, G. Hebrard, S. Blandin, J. Cassier, H. J. Deeg, A. S. Bonomo, F. Bouchy, J. -m. Desert, D. Ehrenreich, M. Deleuil, et al. To cite this version: A. Lecavelier Etangs, G. Hebrard, S. Blandin, J. Cassier, H. J. Deeg, et al.. Search for rings and satellites around the exoplanet CoRoT-9b using Spitzer photometry. Astronomy and Astrophysics - A&A, EDP Sciences, 2017, 603, pp.A115. 10.1051/0004-6361/201730554. hal-01678524 HAL Id: hal-01678524 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01678524 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A&A 603, A115 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201730554 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics Search for rings and satellites around the exoplanet CoRoT-9b using Spitzer photometry A. Lecavelier des Etangs1, G. Hébrard1; 2, S. Blandin1, J. Cassier1, H. J. Deeg3; 4, A. S. Bonomo5, F. Bouchy6, J.-M. Désert7, D. Ehrenreich6, M. Deleuil8, R. F. Díaz9; 10, C. Moutou11, and A. Vidal-Madjar1 1 Institut d’astrophysique de Paris, CNRS, UMR 7095 & Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Paris 6, 98bis Bd Arago, 75014 Paris, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Observatoire de Haute-Provence, CNRS/OAMP, 04870 Saint-Michel-l’Observatoire, France 3 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 4 Universidad de La Laguna, Dept. -

Cassini Observations of Saturn's Irregular Moons

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 12, EPSC2018-103-1, 2018 European Planetary Science Congress 2018 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2018 Cassini Observations of Saturn's Irregular Moons Tilmann Denk (1) and Stefano Mottola (2) (1) Freie Universität Berlin, Germany ([email protected]), (2) DLR Berlin, Germany 1. Introduction two prograde irregulars are slower than ~13 h, while the periods of all but two retrogrades are faster than With the ISS-NAC camera of the Cassini spacecraft, ~13 h. The fastest period (Hati) is much slower than we obtained photometric lightcurves of 25 irregular the disruption rotation barrier for asteroids (~2.3 h), moons of Saturn. The goal was to derive basic phys- indicating that Saturn's irregulars may be rubble piles ical properties of these objects (like rotational periods, of rather low densities, possibly as low as of comets. shapes, pole-axis orientations, possible global color variations, ...) and to get hints on their formation and Table: Rotational periods of 25 Saturnian irregulars evolution. Our campaign marks the first utilization of an interplanetary probe for a systematic photometric Moon Approx. size Rotational period survey of irregular moons. name [km] [h] Hati 5 5.45 ± 0.04 The irregular moons are a class of objects that is very Mundilfari 7 6.74 ± 0.08 distinct from the inner moons of Saturn. Not only are Loge 5 6.9 ± 0.1 ? they more numerous (38 versus 24), but also occupy Skoll 5 7.26 ± 0.09 (?) a much larger volume within the Hill sphere of Suttungr 7 7.67 ± 0.02 Saturn. -

Our Solar System

This graphic of the solar system was made using real images of the planets and comet Hale-Bopp. It is not to scale! To show a scale model of the solar system with the Sun being 1cm would require about 64 meters of paper! Image credit: Maggie Mosetti, NASA This book was produced to commemorate the Year of the Solar System (2011-2013, a martian year), initiated by NASA. See http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/yss. Many images and captions have been adapted from NASA’s “From Earth to the Solar System” (FETTSS) image collection. See http://fettss.arc.nasa.gov/. Additional imagery and captions compiled by Deborah Scherrer, Stanford University, California, USA. Special thanks to the people of Suntrek (www.suntrek.org,) who helped with the final editing and allowed me to use Alphonse Sterling’s awesome photograph of a solar eclipse! Cover Images: Solar System: NASA/JPL; YSS logo: NASA; Sun: Venus Transit from NASA SDO/AIA © 2013-2020 Stanford University; permission given to use for educational and non-commericial purposes. Table of Contents Why Is the Sun Green and Mars Blue? ............................................................................... 4 Our Sun – Source of Life ..................................................................................................... 5 Solar Activity ................................................................................................................... 6 Space Weather ................................................................................................................. 9 Mercury -

CLARK PLANETARIUM SOLAR SYSTEM FACT SHEET Data Provided by NASA/JPL and Other Official Sources

CLARK PLANETARIUM SOLAR SYSTEM FACT SHEET Data provided by NASA/JPL and other official sources. This handout ©July 2013 by Clark Planetarium (www.clarkplanetarium.org). May be freely copied by professional educators for classroom use only. The known satellites of the Solar System shown here next to their planets with their sizes (mean diameter in km) in parenthesis. The planets and satellites (with diameters above 1,000 km) are depicted in relative size (with Earth = 0.500 inches) and are arranged in order by their distance from the planet, with the closest at the top. Distances from moon to planet are not listed. Mercury Jupiter Saturn Uranus Neptune Pluto • 1- Metis (44) • 26- Hermippe (4) • 54- Hegemone (3) • 1- S/2009 S1 (1) • 33- Erriapo (10) • 1- Cordelia (40.2) (Dwarf Planet) (no natural satellites) • 2- Adrastea (16) • 27- Praxidike (6.8) • 55- Aoede (4) • 2- Pan (26) • 34- Siarnaq (40) • 2- Ophelia (42.8) • Charon (1186) • 3- Bianca (51.4) Venus • 3- Amalthea (168) • 28- Thelxinoe (2) • 56- Kallichore (2) • 3- Daphnis (7) • 35- Skoll (6) • Nix (60?) • 4- Thebe (98) • 29- Helike (4) • 57- S/2003 J 23 (2) • 4- Atlas (32) • 36- Tarvos (15) • 4- Cressida (79.6) • Hydra (50?) • 5- Desdemona (64) • 30- Iocaste (5.2) • 58- S/2003 J 5 (4) • 5- Prometheus (100.2) • 37- Tarqeq (7) • Kerberos (13-34?) • 5- Io (3,643.2) • 6- Pandora (83.8) • 38- Greip (6) • 6- Juliet (93.6) • 1- Naiad (58) • 31- Ananke (28) • 59- Callirrhoe (7) • Styx (??) • 7- Epimetheus (119) • 39- Hyrrokkin (8) • 7- Portia (135.2) • 2- Thalassa (80) • 6- Europa (3,121.6) -

Observing the Universe

ObservingObserving thethe UniverseUniverse :: aa TravelTravel ThroughThrough SpaceSpace andand TimeTime Enrico Flamini Agenzia Spaziale Italiana Tokyo 2009 When you rise your head to the night sky, what your eyes are observing may be astonishing. However it is only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum of the Universe: the visible . But any electromagnetic signal, indipendently from its frequency, travels at the speed of light. When we observe a star or a galaxy we see the photons produced at the moment of their production, their travel could have been incredibly long: it may be lasted millions or billions of years. Looking at the sky at frequencies much higher then visible, like in the X-ray or gamma-ray energy range, we can observe the so called “violent sky” where extremely energetic fenoena occurs.like Pulsar, quasars, AGN, Supernova CosmicCosmic RaysRays:: messengersmessengers fromfrom thethe extremeextreme universeuniverse We cannot see the deep universe at E > few TeV, since photons are attenuated through →e± on the CMB + IR backgrounds. But using cosmic rays we should be able to ‘see’ up to ~ 6 x 1010 GeV before they get attenuated by other interaction. Sources Sources → Primordial origin Primordial 7 Redshift z = 0 (t = 13.7 Gyr = now ! ) Going to a frequency lower then the visible light, and cooling down the instrument nearby absolute zero, it’s possible to observe signals produced millions or billions of years ago: we may travel near the instant of the formation of our universe: 13.7 By. Redshift z = 1.4 (t = 4.7 Gyr) Credits A. Cimatti Univ. Bologna Redshift z = 5.7 (t = 1 Gyr) Credits A. -

Evection Resonance in Saturn's Coorbital Moons Dr

Evection resonance in Saturn's coorbital moons Dr. Cristian Giuppone1, Lic Ximena Saad Olivera2, Dr. Fernando Roig2 (1) Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, OAC - IATE, Córdoba, Ar (2) Observatorio Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil OPS III - Diversis Mundi - Santiago - Chile Evection resonance in Saturn's coorbital moons MOTIVATION: recent studies in Jovian planets links the evection resonance and the architecture and evolution of their satellites. Evection resonance in Saturn's coorbital moons MOTIVATION: recent studies in Jovian planets links the evection resonance and the architecture and evolution of their satellites. GOAL: understand the evection resonance in the frame of coorbital motion of Satellites, through numerical evidence of its importance. Evection resonance ● The evection resonance is produced when the orbit pericenter of a satellite (ϖ) precess with the same period that the Sun movement as a perturber (λO) (Brouwer and Clemence, 1961) The evection angle → Ψ=λO – ϖ Satellite Sun Saturn ψ = 0° Evection resonance ● The evection resonance is produced when the orbit pericenter of a satellite (ϖ) precess with the same period that the Sun movement as a perturber (λO) (Brouwer and Clemence, 1961) The evection angle → Ψ=λO – ϖ Satellite Sun Saturn ψ = 0° Evection resonance ● Interior resonance: ● Produced by the oblateness of the planet. ● -3 Located at a ~ 10 RP (a~10 au), and several armonics are present. ● Importance: tides produce outward migration of inner moons. The moons can cross the resonance and may change substantially their orbital elements (e.g. Nesvorny et al 2003, Cuk et al. 2016) Evection resonance ● Interior resonance: ● Produced by the oblateness of the planet. -

Moons of Saturn

National Aeronautics and Space Administration 0 300,000,000 900,000,000 1,500,000,000 2,100,000,000 2,700,000,000 3,300,000,000 3,900,000,000 4,500,000,000 5,100,000,000 5,700,000,000 kilometers Moons of Saturn www.nasa.gov Saturn, the sixth planet from the Sun, is home to a vast array • Phoebe orbits the planet in a direction opposite that of Saturn’s • Fastest Orbit Pan of intriguing and unique satellites — 53 plus 9 awaiting official larger moons, as do several of the recently discovered moons. Pan’s Orbit Around Saturn 13.8 hours confirmation. Christiaan Huygens discovered the first known • Mimas has an enormous crater on one side, the result of an • Number of Moons Discovered by Voyager 3 moon of Saturn. The year was 1655 and the moon is Titan. impact that nearly split the moon apart. (Atlas, Prometheus, and Pandora) Jean-Dominique Cassini made the next four discoveries: Iapetus (1671), Rhea (1672), Dione (1684), and Tethys (1684). Mimas and • Enceladus displays evidence of active ice volcanism: Cassini • Number of Moons Discovered by Cassini 6 Enceladus were both discovered by William Herschel in 1789. observed warm fractures where evaporating ice evidently es- (Methone, Pallene, Polydeuces, Daphnis, Anthe, and Aegaeon) The next two discoveries came at intervals of 50 or more years capes and forms a huge cloud of water vapor over the south — Hyperion (1848) and Phoebe (1898). pole. ABOUT THE IMAGES As telescopic resolving power improved, Saturn’s family of • Hyperion has an odd flattened shape and rotates chaotically, 1 2 3 1 Cassini’s visual known moons grew. -

Moons of Saturn National Aeronautics and Space Administration Moons of Saturn

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Moons of Saturn www.nasa.gov National Aeronautics and Space Administration Moons of Saturn www.nasa.gov Saturn, the sixth planet from the Sun, is home to a vast array of • Phoebe orbits the planet in a direction opposite that of Saturn’s • Closest Moon to Saturn Pan intriguing and unique worlds. From the cloud-shrouded surface larger moons, as do several of the recently discovered moons. Pan’s Distance from Saturn 133,583 km (83,022 mi) of Titan to crater-riddled Phoebe, each of Saturn’s moons tells • Mimas has an enormous crater on one side, the result of an • Fastest Orbit Pan another piece of the story surrounding the Saturn system. impact that nearly split the moon apart. Pan’s Orbit Around Saturn 13.8 hours Christiaan Huygens discovered the first known moon of Saturn. • Enceladus displays evidence of active ice volcanism: Cassini • Number of Moons Discovered by Voyager 3 The year was 1655 and the moon is Titan. Jean-Dominique Cas- observed warm fractures where evaporating ice evidently escapes (Atlas, Prometheus, and Pandora) sini made the next four discoveries: Iapetus (1671), Rhea (1672), and forms a huge cloud of water vapor over the south pole. • Number of Moons Discovered by Cassini (So Far) 4 Dione (1684), and Tethys (1684). Mimas and Enceladus were • Hyperion has an odd flattened shape and rotates chaotically, (Methone, Pallene, Polydeuces, and the moonlet 2005S1) both discovered by William Herschel in 1789. The next two probably due to a recent collision. discoveries came at intervals of 50 or more years — Hyperion ABOUT THE IMAGES • Pan orbits within the main rings and helps sweep materials out 1 An ultraviolet (1848) and Phoebe (1898). -

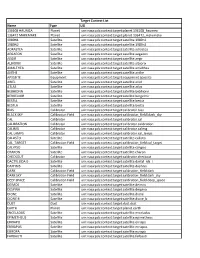

PDS4 Context List

Target Context List Name Type LID 136108 HAUMEA Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136108_haumea 136472 MAKEMAKE Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136472_makemake 1989N1 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n1 1989N2 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n2 ADRASTEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.adrastea AEGAEON Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegaeon AEGIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegir ALBIORIX Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.albiorix AMALTHEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.amalthea ANTHE Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.anthe APXSSITE Equipment urn:nasa:pds:context:target:equipment.apxssite ARIEL Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.ariel ATLAS Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.atlas BEBHIONN Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bebhionn BERGELMIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bergelmir BESTIA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestia BESTLA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestla BIAS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.bias BLACK SKY Calibration Field urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibration_field.black_sky CAL Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal CALIBRATION Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calibration CALIMG Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calimg CAL LAMPS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal_lamps CALLISTO Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.callisto