Creative Writing Portfolio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCWC WAG Creative Writing

GASTON COLLEGE Creative Writing Writing Center I. GENERAL PURPOSE/AUDIENCE Creative writing may take many forms, such as fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, playwriting, and screenwriting. Creative writers can turn almost any situation into possible writing material. Creative writers have a lot of freedom to work with and can experiment with form in their work, but they should also be aware of common tropes and forms within their chosen style. For instance, short story writers should be aware of what represents common structures within that genre in published fiction and steer away from using the structures of TV shows or movies. Audiences may include any reader of the genre that the author chooses to use; therefore, authors should address potential audiences for their writing outside the classroom. What’s more, students should address a national audience of interested readers—not just familiar readers who will know about a particular location or situation (for example, college life). II. TYPES OF WRITING • Fiction (novels and short stories) • Creative non-fiction • Poetry • Plays • Screenplays Assignments will vary from instructor to instructor and class to class, but students in all Creative Writing classes are assigned writing exercises and will also provide peer critiques of their classmates’ work. In a university setting, instructors expect prose to be in the realistic, literary vein unless otherwise specified. III. TYPES OF EVIDENCE • Subjective: personal accounts and storytelling; invention • Objective: historical data, historical and cultural accuracy: Work set in any period of the past (or present) should reflect the facts, events, details, and culture of its time and place. -

Stream of Consciousness: a Study of Selected Novels by James Joyce and Virginia Woolf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Italian translations of English stream of consciousness: a study of selected novels by James Joyce and Virginia Woolf Giulia Totò PhD The University of Edinburgh 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis was composed by myself, that the work contained herein is my own except where explicitly stated otherwise in the text, and that this work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Giulia Totò iii To little Emma and Lucio, for the immense joy they spread and the love they allow me to return. iv Acknowledgments I am pleased to take this opportunity to thank my supervisors Federica G. Pedriali and Yves Gambier for their guidance and, most of all, for their support and patience during these years. -

CREATIVE WRITING PROGRAM Creative Writing ASSOCIATE of ARTS DEGREE (AA) REQUIRED CREDITS: 61 DEGREE CODE: ENGCW-AA

CREATIVE WRITING PROGRAM Creative Writing ASSOCIATE OF ARTS DEGREE (AA) REQUIRED CREDITS: 61 DEGREE CODE: ENGCW-AA DESCRIPTION The AA degree with a Creative Writing emphasis focuses on the writing of fiction or poetry. As knowledge of the genres and traditions of literature is central to the development of a writer or poet, courses that include the study of the elements of fiction and poetry are integrated into the program. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES • Demonstrate knowledge and use of the forms and component elements of the genre (fiction or poetry). • Identify purpose and audience within the context of fiction or poetry. • Understand literary elements such as use of character, setting point of view, plot, style, and theme for fiction; metaphor, simile, meter, symbol, allusion, narrative, and theme for poetry. • Complete a portfolio with work that exhibits effective use of language, self-editing, and controlled voice in a given genre. PLEASE NOTE - The courses listed below may require a prerequisite or corequisite. Read course descriptions before registering for classes. All MATH and ENG courses numbered 01-99 must be completed before reaching 30 total college-level credits. No course under 100-level counts toward degree completion. GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS (34 CREDITS) SPECIAL PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS (27 CREDITS) MATHEMATICS (3 credits) CORE REQUIREMENTS (15 credits) MATH 120 or 124 or above; or STAT 152 International Languages 111 or above 8 (courses must be in a single language) ENGLISH COMPOSITION (6-8 credits) See AA/AB/AS policy p. 45 for courses COM 101 Oral Communication 3 ENG 205 Introduction to Creative Writing: Fiction and Poetry 3 LITERATURE (3 credits) ENG 296 Portfolio Assessment 1 See AA/AB/AS policy p. -

English 138 - Topics in Creative Writing: Writing Screenplays

English 138 - Topics in Creative Writing: Writing Screenplays Hasmik Ekimyan [email protected] 818-726-0392 Course Description Students will learn the art of screenwriting and will have the opportunity to practice this art through the creation of an original story. Throughout the course students will develop their original screenplays, learning how to craft story, plot, character, dialogue, and theme, enabling them to produce a full outline and the First Act of their screenplays. Grading Participation: 20% Assignments: 40% First Act: 40% Office Hours: To be determined. Reading Suggestions There are no reading assignments for this class. However, if you are interested in further developing your skills, here is a list that you may find useful. -If you want to know more about screenwriting, these may help: --Richard Walter, Essentials of Screenwriting --Hal Ackerman, Write Screenplays that Sell the Ackerman Way --Lew Hunter, Lew Hunter’s Screenwriting 434 --Aristotle, Poetics (Nota Bene: good for story) --Lajos Egri, The Art of Dramatic Writing (Nota Bene: good for character) -If you want to know more about the art of film in general, this may help: --Howard Suber, The Power of Film -If you want to be the best writer you can possibly be, commit these to memory: --The complete works of William Shakespeare -If you want to know the answers to life’s questions, read these: --The complete works of Fyodor Dostoevsky --The complete works of Leo Tolstoy Assignments First Act: Your final assignment will be the completed First Act of your screenplays (20-30 pages). We will work on these pages throughout the course. -

The Power of Short Stories, Novellas and Novels in Today's World

International Journal of Language and Literature June 2016, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 21-35 ISSN: 2334-234X (Print), 2334-2358 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2015. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijll.v4n1a3 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijll.v4n1a3 The Power of Short Stories, Novellas and Novels in Today’s World Suhair Al Alami1 Abstract The current paper highlights the significant role literature can play within EFL contexts. Focusing mainly on short stories, novellas and novels, the paper seeks to discuss five points. These are: main elements of a short story/novella/novel, specifications of a short story/novella/novel-based course, points for instructors to consider whilst dealing with a short story/novella/novel within EFL contexts, recommended approaches which instructors may employ in the EFL classroom whilst discussing a short story/novella/novel, and language assessment of EFL learners using a short story/novella/novel-based course. Having discussed the aforementioned points, the current paper proceeds to present a number of recommendations for EFL teaching practitioners to consider. Keywords: Short Stories; Novellas; Novels Abbreviation: EFL (English as a Foreign Language) 1. Introduction In an increasingly demanding and competitive world, students need to embrace the four Cs: communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity. Best practices in the twenty-first century education, therefore, require practical tools that facilitate student engagement, develop life skills, and build upon a solid foundation of research whilst supporting higher-level thinking. With the four Cs in mind, the current paper highlights the significant role literature can play within EFL contexts. -

Sophie Masson Breaking the Pattern: Established Writers Undertaking Creative Writing Doctorates in Australia

Sophie Masson TEXT Vol 20 No 2 University of New England Sophie Masson Breaking the pattern: Established writers undertaking creative writing doctorates in Australia Abstract The focus of this article is an examination of the experiences of established writers who have recently completed, or are currently undertaking, a creative writing doctorate, against a background of change within the publishing industry. Is it primarily financial/career or creative control concerns that are influencing established writers to undertake creative doctorates in recent times? And how do these writers fare within the degree program? To explore these issues through individual stories, interviews were conducted, by email and phone, with six established professional writers who had recently completed, or were still undertaking, a creative doctorate as well as with four established creative writing academics, most of whom are authors themselves. Questions of motivation and experience, as well as outcome, are canvassed in this piece of original research, which provides an interesting snapshot of the current situation for established writers in Australia undertaking creative writing doctorates. Keywords: creative writing doctorates, creative writing PhDs, publishing creative writing PhDs Introduction In 2001 Nigel Krauth, writing in TEXT, observed that there were only eight universities in Australia offering creative writing doctorates, as against 37 offering creative writing degrees at lower levels than the doctorate (Krauth 2001). Just eight years later, however, much had changed. In her paper, Describing the creative writing thesis: a census of creative writing doctorates, 1993-2008 published in TEXT in 2009, Nicola Boyd reported that 27 Australian universities offered a variant of the creative writing doctorate, with 199 creative writing PhDs, DCAs, and doctorates awarded between June 1993, when the first one (to Graeme Harper at UTS) was awarded, to June 2008, when her survey ended. -

Creative Writing Invitation VII: Character Development and Dialogue?

Creative Writing Invitation #7 Character Development and "Dialogue" Part 1: Please read these two passages of dialogue by Ernest Hemingway: "What should we drink?" the girl asked. She had taken off her hat and put it on the table. "It's pretty hot," the man said. "Let's drink beer." "Dos cervesas," the man said into the curtain. "Big ones?" a woman asked from the doorway. "Yes. Two big ones." The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the felt pads and the beer glasses on the table and looked at the man and the girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun and the country was brown and dry. "They look like white elephants," she said. "I've never seen one," the man drank his beer. "No, you wouldn't have." "I might have," the man said. "Just because you say I wouldn't doesn't prove anything." -- from Hills Like White Elephants The door of Henry's lunch-room opened and two men came in. They sat down at the counter. "What's yours?" George asked them. "I don't know," one of the men said. "What do you want to eat, Al?" "I don't know," said Al. "I don't know what I want to eat." Outside it was getting dark. The street-light came on outside the window. The two men at the counter read the menu. From the other end of the counter Nick Adams watched them. He had been talking to George when they came in. -

Hiker Accounts of Living Among Wildlife on the Appalachian Trail

Wild Stories on the Internet: Hiker Accounts of Living Among Wildlife on the Appalachian Trail Submitted by Katherine Susan Marx to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthrozoology In July 2018 This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has been previously submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………. Abstract The Appalachian Trail is the world’s longest hiking-only trail, covering roughly 2,200 miles of forest, mountains, ridges and plains. Each year a few thousand people set out to hike the entire length of the trail, estimated to take between five and seven months to complete. Numerous species of autonomous animals – wildlife – dwell on and around the trail, and it is the encounters that happen between these human and nonhuman animals that are the focus of this thesis. The research presented here is based wholly around narratives posted online as blogs by 166 Appalachian Trail hikers during the years 2015 and 2016. These narratives provide an insight into how hikers related to the self-directed animals that they temporarily shared a home with. Several recurring themes emerged to form the basis of the thesis chapters: many hikers viewed their trek as akin to a pilgrimage, which informed their perception of the animals that they encountered; American Black Bears (Ursus americanus), viewed as emblematic of the trail wilderness, made dwelling on the trail satisfyingly risky; hikers experienced strong feelings about some animals as being cute, and about others as being disgusting; along a densely wooded trail, experience of animals was often primarily auditory; the longer that they spent on the trail, the more hikers themselves experienced a sense of becoming wild. -

From Shadow Citizens to Teflon Stars

From shadow citizens to teflon stars cultural responses to the digital actor L i s a B o d e A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2004 School of Theatre, Film and Dance University of New South Wales Abstract This thesis examines an intermittent uncanniness that emerges in cultural responses to new image technologies, most recently in some impressions of the digital actor. The history of image technologies is punctuated by moments of fleeting strangeness: from Maxim Gorky’s reading of the cinematographic image in terms of “cursed grey shadows,” to recent renderings of the computer-generated cast of Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within as silicon-skinned mannequins. It is not merely the image’s unfamiliar and new aesthetics that render it uncanny. Rather, the image is received within a cultural framework where its perceived strangeness speaks allegorically of what it means to be human at that historical moment. In various ways Walter Benjamin, Anson Rabinbach and N. Katherine Hayles have claimed that the notion and the experience of “being human” is continuously transformed through processes related to different stages of modernity including rational thought, industrialisation, urbanisation, media and technology. In elaborating this argument, each of the four chapters is organized around the elucidation of a particular motif: “dummy,” “siren,” “doppelgänger” and “resurrection.” These motifs circulate through discourses on different categories of digital actor, from those conceived without physical referents to those that are created as digital likenesses of living or dead celebrities. These cultural responses suggest that even while writers on the digital actor are speculating about the future, they are engaging with ideas about life, death and identity that are very old and very ambivalent. -

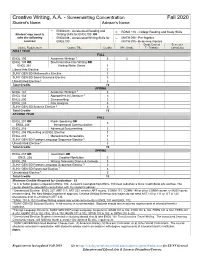

Creative Writing, A.A. - Screenwriting Concentration Fall 2020 Student's Name: Advisor's Name

Creative Writing, A.A. - Screenwriting Concentration Fall 2020 Student's Name: Advisor's Name: ENGL049 - Accelerated Reading and RDNG 116 - College Reading and Study Skills Student may need to Writing Skills for ENGL100 OR take the following ENGL098 - Accelerated Writing Skills for MATH 090 - Pre-Algebra courses: ENGL100 MATH 095 - Beginning Algebra Grade Earned Semester Course Requirement Course Title Credits Min. Grade T - Transfer Completed FIRST YEAR FALL ENGL 100 Academic Writing I 1 3 C ENGL 135 OR Short Narrative Film Writing OR ENGL 261 Visiting Writer Series 1 Liberal Arts Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Mathematics Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Social Sciences Elective 3 Unrestricted Elective 2 3 Total Credits 16 SPRING ENGL 101 Academic Writing II 3 3 ENGL 102 Approaches to Literature 3 3 ENGL 200 Screenwriting 3 ENGL 233 Film Analysis 3 SUNY GEN ED Science Elective 4 3 Total Credits 15 SECOND YEAR FALL ENGL 201 OR Public Speaking OR 3 ENGL 204 Interpersonal Communication ENGL 216 Advanced Screenwriting 3 ENGL 256 Playwriting or ENGL Elective 3 ENGL 274 Marketing the Screenplay 1 SUNY GEN ED Foreign Language Sequence Elective 5 3 Unrestricted Elective 6 3 Total Credits 16 SPRING ENGL 237 OR Journalism OR ENGL 258 Creative Nonfiction 3 ENGL 255 Writing Television Drama & Comedy 3 5 SUNY GEN ED Foreign Language Sequence Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Restricted Elective 7 3 Unrestricted Elective 6 3 Total Credits 15 Minimum Credits Required for Graduation: 62 1 A C or better grade is required in ENGL 100. A student exempted from ENGL 100 must substitute a three credit liberal arts elective. -

Creative Writing, BFA 1

Creative Writing, BFA 1 CREATIVE WRITING, BFA Banner Code: LA-BFA-CW ENGH 302 Advanced Composition (Mason Core)) with a minimum GPA of 2.00. A487 Robinson Hall Fairfax Campus At the discretion of the department, transfer students may substitute transferred lower level creative writing classes for some BFA Website: creativewriting.gmu.edu/programs/la-bfa-cw requirements. With permission of the department, BFA students may select a substitute for concentration required coursework from the list The Bachelor of Fine Arts in Creative Writing is one of only thirty BFAs of courses approved for the writing or literature elective requirement. in creative writing available nationwide. With three concentrations to Substitutions must be justified as specifically relevant to the student's choose from—fiction, poetry, nonfiction—the BFA is structured to give study. Substitutions will not satisfy more than one requirement within the students ample opportunity to learn to write and think creatively while major. also developing the vocational writing skills that are desperately needed in the workplace. All students pursuing a BFA are strongly advised to Requirements complete on-site workplace internships in writing-intensive environments, and finish the degree with a submission of a portfolio of work as part of a final-semester capstone course. Degree Requirements Total credits: minimum 120 Admissions & Policies Students should be aware of the specific policies associated with this program, located on the Admissions & Policies tab. Admissions Students will complete 21 credits of BFA core requirements, 12 credits Acceptance into the program is competitive. Admission to the university from one of 3 concentrations, and 12 credits in English department does not guarantee admission to the BFA program. -

COM 208: Creative Writing: Poetry Catalog Description Evaluation Assessment Grading Scale

Communication and Creative & Performing Arts Division 1400 Tanyard Road, Sewell, NJ 08080 856-468-5000\ COM 208: Creative Writing: Poetry Syllabus Lecture Hours/Credits: 3/3 Catalog Description Prerequisite: ENG 101 Students study a variety of short fiction for story structure and write several short stories. Students also share portions of their stories in progress, demonstrating, for example, narrative point-of- view, dialogue, and significant setting. They prepare at least one story for submission to a magazine or literary journal. Textbook and Course Materials It is the responsibility of the student to confirm with the bookstore and/or their instructor the textbook, handbook and other materials required for their specific course and section. Click here to see current textbook prices at rcgc.bncollege.com. Evaluation Assessment Online Proctoring All courses offered at RCSJ, whether they are web-enhanced, hybrid, or fully online, may include assessments that make use of Online Proctoring. To find out more about Online Proctoring, and to learn about the minimum technical requirements, visit rcsj.edu/elearning/online-proctoring. Grading Scale The grading scale for each course and section will be determined by the instructor and distributed the first day of class. 1 Revised Fall 2018 Rowan College South Jersey Core Competencies (Based on the NJCC General Education Foundation - August 15, 2007; Revised 2011) This comprehensive list reflects the core competencies that are essential for all RCSJ graduates; however, each program varies regarding competencies required for a specific degree. Critical thinking is embedded in all courses, while teamwork and personal skills are embedded in many courses. 1.