East Texas Historical Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America's Favorite Pastime

America’s favorite pastime Birmingham-Southern College has produced a lot exhibition games against major league teams, so Hall of talent on the baseball field, and Fort Worth Cats of Famers like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe shortstop Ricky Gomez ’03 is an example of that tal- DiMaggio, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Pee ent. Wee Reese,Ted Williams, Stan Musial, and Hank Gomez, who played on BSC’s 2001 NAIA national Aaron all played exhibition games at LaGrave Field championship team, is in his second year with the against the Cats. Cats, an independent professional minor league club. Gomez encourages BSC faithful to visit Fort Prior to that, he played for two years with the St. Worth to see a game or two. Paul Saints. “It is a great place to watch a baseball game and The Fort Worth Cats play in the Central Baseball there is a lot to do in Fort Worth.” League. The team has a rich history in baseball He also attributes much of his success to his expe- going back to 1888. The home of the Cats, LaGrave riences at BSC. Field, was built in 2002 at the same location of the “To this day, I talk to my BSC teammates and to old LaGrave Field (1926-67). Coach Shoop [BSC Head Coach Brian], who was Many famous players have worn the uniform of not only a great coach, but a father figure. the Cats including Maury Wills and Hall of Famers Birmingham-Southern has a great family atmos- Rogers Hornsby, Sparky Anderson, and Duke Snider. -

Prior Player Transfers

American Association Player Transfers 2020 AA Team Position Player First Name Player Last Name MLB Team Kansas City T-Bones RHP Andrew DiPiazza Colorado Rockies Chicago Dogs LHP Casey Crosby Los AngelesDodgers Lincoln Saltdogs RHP Ricky Knapp Los AngelesDodgers Winnipeg Goldeyes LHP Garrett Mundell Milwaukee Brewers Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks RHP Grant Black St. LouisCardinals Kansas City T-Bones RHP Akeem Bostick St. LouisCardinals Chicago Dogs LHP D.J. Snelten Tampa BayRays Sioux City Explorers RHP Ryan Newell Tampa BayRays Chicago Dogs INF Keon Barnum Washington Nationals Sioux City Explorers INF Jose Sermo Pericos de Puebla Chicago Dogs OF David Olmedo-Barrera Pericos de Puebla Sioux City Explorers INF Drew Stankiewicz Toros de Tijuana Gary SouthShore Railcats RHP Christian DeLeon Toros de Tijuana American Association Player Transfers 2019 AA Team Position Player First Name Player Last Name MLB Team Sioux City Explorers RHP Justin Vernia Arizona Diamondbacks Sioux Falls Canaries RHP Ryan Fritze Arizona Diamondbacks Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks RHP Bradin Hagens Arizona Diamondbacks Winnipeg Goldeyes INF Kevin Lachance Arizona Diamondbacks Gary SouthShore Railcats OF Evan Marzilli Arizona Diamondbacks St. Paul Saints OF Max Murphy Arizona Diamondbacks Texas AirHogs INF Josh Prince Arizona Diamondbacks Texas AirHogs LHP Tyler Matzek Atlanta Braves Milwaukee Milkmen INF Angelo Mora BaltimoreOrioles Sioux Falls Canaries RHP Dylan Thompson Boston Red Sox Gary SouthShore Railcats OF Edgar Corcino Boston Red Sox Kansas City T-Bones RHP Kevin Lenik Boston Red Sox Gary SouthShore Railcats OF Colin Willis Boston Red Sox St. Paul Saints C Justin O’Conner Chicago White Sox Sioux City Explorers RHP James Dykstra CincinnatiReds Kansas City T-Bones LHP Eric Stout CincinnatiReds St. -

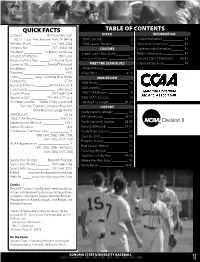

QUICK FACTS TABLE of CONTENTS Location______Rohnert Park, Calif INTRO INFORMATION 1801 E

QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location ______________ Rohnert Park, Calif INTRO INFORMATION 1801 E. Cotati Ave., Rohnert Park, CA 94928 2009 Schedule _______________ 2 CCAA Information ____________ 42 Athletics Phone __________ (707) 664-2358 2009 Season Preview __________ 3 Opponent Information ________ 43 Athletics Fax _____________ (707) 664-4104 COACHES Department Information _______ 44 President ___________ Dr. Ruben Armiñana Head Coach John Goelz ________ 4 Media Information ____________ 45 Director of Athletics ____________ Bill Fusco Assistant Coaches ___________5-6 Sonoma State Information ____46-47 Faculty Athletic Rep. ______Dr. Duane Dove Home Facility __________ Seawolf Diamond MEET THE SEAWOLVES Corporate Sponsors ___________ 48 Enrollment ______________________ 8,274 2008-09 Roster _______________ 7 Founded _______________________ 1961 Player Bios ________________8-15 Colors_________Navy, Columbia Blue, White 2008 REVIEW Conference _____________________CCAA 2008 Results _________________ 16 National Affiliation ________NCAA Division II 2008 Statistics _______________ 17 Head Coach ________________ John Goelz Coach’s Phone ___________ (707) 664-2524 2008 CCAA Review ___________ 18 Record at SSU _________ 791-493-5 (23 yrs.) 2008 CCAA Statistics __________ 19 Assistant Coaches _ Walter White, Derek Bell The Road To Sauget _________20-24 Dolf Hes, Esteban Contreras, Brett Kim, HISTORY Mike Nackord, Gregg Adams Yearly Starting Lineups ________ 25 2008 Record _____________________ 52-15 All-Time Honors ____________26-27 2008 -

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan April2006 United States Department of the Interior FISH AND Wll...DLIFE SERVICE P.O. Box 1306 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 In Reply Refer To: R2/NWRS-PLN JUN 0 5 2006 Dear Reader: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is proud to present to you the enclosed Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) for the Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge (Refuge). This CCP and its supporting documents outline a vision for the future of the Refuge and specifies how this unique area can be maintained to conserve indigenous wildlife and their habitats for the enjoyment of the public for generations to come. Active community participation is vitally important to manage the Refuge successfully. By reviewing this CCP and visiting the Refuge, you will have opportunities to learn more about its purpose and prospects. We invite you to become involved in its future. The Service would like to thank all the people who participated in the planning and public involvement process. Comments you submitted helped us prepare a better CCP for the future of this unique place. Sincerely, Tom Baca Chief, Division of Planning Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Sherman, Texas Prepared by: United States Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Planning Region 2 500 Gold SW Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 Comprehensive conservation plans provide long-term guidance for management decisions and set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes and identify the Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. -

TML NO HITTERS 1951-2017 No

TML NO HITTERS 1951-2017 No. YEAR NAME TEAM OPPONENT WON/LOST NOTES 1 1951 Hal Newhouser Duluth Albany Won 2 1951 Marlin Stuart North Adams Summer Won 3 1952 Ken Raffensberger El Dorado Walla Walla Won 4 1952Billy Pierce Beverly Moosen Won 5 1953 Billy Pierce North Adams El Dorado Won 2nd career 6 1955 Sam Jones El Dorado Beverly Won 1-0 Score, 4 W, 8 K 7 1956 Jim Davis Cheticamp Beverly Won 2-1 Score, 4 W, 2 HBP 8 1956 Willard Schmidt Beverly Duluth Won 1-0 Score, 10 IP 9 1956 Don Newcombe North Adams Summer Won 4-1 Score, 0 ER 10 1957 Bill Fischer Cheticamp Summer Won 2 W, 5 K 11 1957 Billy Hoeft Albany Beverly Won 2 W, 7 K 12 1958 Joey Jay Moosen Bloomington Won 5 W, 9 K 13 1958 Bob Turley Albany Beverly Won 14 1959 Sam Jones Jupiter Sanford Won 15 K, 2nd Career 15 1959 Bob Buhl Jupiter Duluth Won Only 88 pitches 16 1959 Whitey Ford Coachella Vly Duluth Won 8 walks! 17 1960 Larry Jackson Albany Duluth Won 1 W, 10 K 18 1962 John Tsitouris Cheticamp Arkansas Won 13 IP 19 1963 Jim Bouton & Cal Koonce Sanford Jupiter Won G5 TML World Series 20 1964 Gordie Richardson Sioux Falls Cheticamp Won 21 1964 Mickey Lolich Sanford Pensacola Won 22 1964 Jim Bouton Sanford Albany Won E5 spoiled perfect game 23 1964 Jim Bouton Sanford Moosen Won 2nd career; 2-0 score 24 1965 Ray Culp Cheticamp Albany Won *Perfect Game* 25 1965 George Brunet Coopers Pond Duluth Won E6 spoiled perfect game 26 1965 Bob Gibson Duluth Hackensack Won 27 1965 Sandy Koufax Sanford Coachella Vly Won 28 1965 Bob Gibson Duluth Coachella Vly Won 2nd career; 1-0 score 29 1965 Jim -

Mathematics for the Liberal Arts

Mathematics for Practical Applications - Baseball - Test File - Spring 2009 Exam #1 In exercises #1 - 5, a statement is given. For each exercise, identify one AND ONLY ONE of our fallacies that is exhibited in that statement. GIVE A DETAILED EXPLANATION TO JUSTIFY YOUR CHOICE. 1.) "According to Joe Shlabotnik, the manager of the Waxahachie Walnuts, you should never call a hit and run play in the bottom of the ninth inning." 2.) "Are you going to major in history or are you going to major in mathematics?" 3.) "Bubba Sue is from Alabama. All girls from Alabama have two word first names." 4.) "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but please don't give me a ticket. I've had a hard day, and I was just trying to get over to my aged mother's hospital room, and spend a few minutes with her before I report to my second full-time minimum-wage job, which I have to have as the sole support of my thirty-seven children and the nineteen members of my extended family who depend on me for food and shelter." 5.) "Former major league pitcher Ross Grimsley, nicknamed "Scuzz," would not wash or change any part of his uniform as long as the team was winning, believing that washing or changing anything would jinx the team." 6.) The part of a major league infield that is inside the bases is a square that is 90 feet on each side. What is its area in square centimeters? You must show the use of units and conversion factors. -

1872: Survivors of the Texas Revolution

(from the 1872 Texas Almanac) SURVIVORS OF THE TEXAS REVOLUTION. The following brief sketches of some of the present survivors of the Texas revolution have been received from time to time during the past year. We shall be glad to have the list extended from year to year, so that, by reference to our Almanac, our readers may know who among those sketches, it will be seen, give many interesting incidents of the war of the revolution. We give the sketches, as far as possible, in the language of the writers themselves. By reference to our Almanac of last year, (1871) it will be seen that we then published a list of 101 names of revolutionary veterans who received the pension provided for by the law of the previous session of our Legislature. What has now become of the Pension law? MR. J. H. SHEPPERD’S ACCOUNT OF SOME OF THE SURVIVORS OF THE TEXAS REVOLUTION. Editors Texas Almanac: Gentlemen—Having seen, in a late number of the News, that you wish to procure the names of the “veteran soldiers of the war that separated Texas from Mexico,” and were granted “pensions” by the last Legislature, for publication in your next year’s Almanac, I herewith take the liberty of sending you a few of those, with whom I am most intimately acquainted, and now living in Walker and adjoining counties. I would remark, however, at the outset, that I can give you but little information as to the companies, regiments, &c., in which these old soldiers served, or as to the dates, &c., of their discharges. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

Taps Critics of Negro Teachers Now Back MU, Sunday

y M a. lj I ï t VOLUME 32, NUMBER 43 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, SATURDAY, APRIL 4, 1964 PRICE TEN CENTS CT /■ ■ ■ 4 ? Is ■ -• A v v-1 ' ’; (Lost in 0, Series of Two Articles) white patrons and no misunder some. We don’t have as many out- After spending $25 or $30 catching t:Hbtel and Mot .i - “I believe a we used to. I think a person should opened my business, it was not jwrt standing at all." of-town guests as we used to, but a sale, we should be 'able to get ■;person should go anywhere he exercise his rights and go where he ■' Has desegregation In Memphis helped or hurt Negro busi for the Negro. I just opened a busi MRS. JANA PORTER Of Uni; I am afraid to say If it will help refreshments, not caring where." ichoose. I haven’t lost any business pleases." ness, we always try to keep it as nesses? During the many years of all-out segregation,, Negroes versl Life Insurance Co. Cafeteria or not We will just have -o run MRS. B. M, 8IMS of The Flame nt, ill and am expecting more In Competing with white florists attractive as possible and try ; who operated hotels, motels, restaurants, cafes and taxicabs in — “It hasn’t hurt us a tall. In fact on and see what the end will be.1’ Cafe, 388 Outer Parkway — "It has the future." Is nothing new for Mrs. Flora Io have what the people want tor -the Bluff City knew thaf the 'so-called Negro market belonged It Is better. -

Houston Astros (35-47) Vs. Detroit Tigers (44-33) RHP Scott Feldman (3-5, 4.00) Vs

Minute Maid Park 5O1 Crawford St. Houston, TX 77OO2 Phone 713.259.8900 Houston Astros (35-47) vs. Detroit Tigers (44-33) RHP Scott Feldman (3-5, 4.00) vs. LHP Drew Smyly (4-6, 3.19) Sunday, June 29, 2014 • Minute Maid Park • Houston, TX • 1:10 p.m. CT • CSN Houston GAME #83 ................HOME #43 THIS HOMESTAND: The Astros will continue a ON THE MEND: The Astros have two players ABOUT THE RECORD nine-day, nine-game homestand today with the on their active roster who are on the mend in CF Overall Record: ......................35-47 last of three vs. Detroit...Houston hosted Atlanta Dexter Fowler (back stiffness) and LHP Dallas Home Record: ........................19-23 (1-2) earlier this week and will host Seattle for Keuchel (left wrist inflammation)...Fowler has --with Roof Open: ...................... 8-8 three next week...the Astros are 2-3 on this not started each of the last two games, while --with Roof Closed: ...................9-15 homestand...coming into this week, Houston has Keuchel had his scheduled start skipped yester- --with Roof Open/Closed: ......... 2-0 had winning records in three consecutive home- day...Houston also has one player on an active Road Record: ..........................16-24 stands for the first time since posting five straight rehab assignment in RHP Anthony Bass, who Current Streak: ...................... Lost 1 winning homestands in 2010 (July-September). has made two appearances for Class A Quad Current Homestand: .................. 2-3 Cities (0ER/2IP). Last Road Trip: .......................... 1-5 BY COMPARISON: By reaching the 35-win Last 5 Games: ............................ 2-3 mark, the Astros have eclipsed their win total BEST IN THE AL: 2B Jose Altuve enters today’s Last 10 Games: ......................... -

'Steely Eyes,' Chaw in Cheek, Dressing-Down Style – Zimmer Had Many Faces

‘Steely eyes,’ chaw in cheek, dressing-down style – Zimmer had many faces By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Friday, June 6th, 2014 Everybody knew the multiple sides – and resulting expressive faces – of Don Zimmer when they shoehorned themselves into his Wrigley Field manager’s office the late afternoon of Friday, Sept. 8, 1989. All had seen and enjoyed the cheru- bic, cheeky chaw-cradling “Popeye” image of Zimmer has he held court, telling stories of his already- astounding 38-year journey through baseball. He had taken the Cubs a long way already, to first place with three weeks to go in this shocking season, and had won friends and influenced people. Yet the media masses also had wit- nessed the darker side of Zimmer. There was the quick temper and jump-down-the-throat style of an old-school baseball lifer with few personal refinements. Above all, the eyes had it, transforming the cherub Don Zimmer (left) confers with Andre Dawson at spring into something seemingly a lot more training before the memorable 1989 season. Photo cred- sinister. it Boz Bros. “He had those steely eyes,” said then Cubs outfielder Gary Varsho. “When he was mad, his eyes opened wide and they penetrated through you. One day I got picked off after www.ChicagoBaseballMuseum.org [email protected] leading off ninth with a single. Oh, my God, coming back to the dugout facing those steely blue eyes.” On this day, the assembled media waited for the bulging eye sockets, the reddened face and the possible verbal outburst. Zimmer and buddy Jim Frey, doubling as Cubs general manager, appeared as if they lost their best friend.