PITSEOLAK ASHOONA Life & Work by Christine Lalonde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Inuit Drawing

Cracking the Glass Ceiling: Contemporary Inuit Drawing Nancy Campbell A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ART HISTORY, YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO. January 2017 © Nancy Campbell, 2017 Abstract The importance of the artist’s voice in art historical scholarship is essential as we emerge from post-colonial and feminist cultural theory and its impact on curation, art history, and visual culture. Inuit art has moved from its origins as an art representing an imaginary Canadian identity and a yearning for a romantic pristine North to a practice that presents Inuit identity in their new reality. This socially conscious contemporary work that touches on the environment, religion, pop culture, and alcoholism proves that Inuit artists can respond and are responding to the changing realities in the North. On the other side of the coin, the categories that have held Inuit art to its origins must be reconsidered and integrated into the categories of contemporary art, Indigenous or otherwise, in museums that consider work produced in the past twenty years to be contemporary as such. Holding Inuit artists to a not-so-distant past is limiting for the artists producing art today and locks them in a history that may or may not affect their work directly. This dissertation examines this critical shift in contemporary Inuit art, specifically drawing, over the past twenty years, known as the contemporary period. The second chapter is a review of the community of Kinngait and the role of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative in the dissemination of arts and crafts. -

Celebrating 30 Years of Supporting Inuit Artists

Celebrating 30 Years of Supporting Inuit Artists Starting on June 3, 2017, the Inuit Art Foundation began its 30th Similarly, the IAF focused on providing critical health and anniversary celebrations by announcing a year-long calendar of safety training for artists. The Sananguaqatiit comic book series, as program launches, events and a special issue of the Inuit Art Quarterly well as many articles in the Inuit Artist Supplement to the IAQ focused that cement the Foundation’s renewed strategic priorities. Sometimes on ensuring artists were no longer unwittingly sacrificing their called Ikayuktit (Helpers) in Inuktut, everyone who has worked health for their careers. Though supporting carvers was a key focus here over the years has been unfailingly committed to helping Inuit of the IAF’s early programming, the scope of the IAF’s support artists expand their artistic practices, improve working conditions extended to women’s sewing groups, printmakers and many other for artists in the North and help increase their visibility around the disciplines. In 2000, the IAF organized two artist residencies globe. Though the Foundation’s approach to achieving these goals for Nunavik artists at Kinngait Studios in Kinnagit (Cape Dorset), NU, has changed over time, these central tenants have remained firm. while the IAF showcased Arctic fashions, film, performance and The IAF formed in the late 1980s in a period of critical transition other media at its first Qaggiq in 1995. in the Inuit art world. The market had not yet fully recovered from The Foundation’s focus shifted in the mid-2000s based on a the recession several years earlier and artists and distributors were large-scale survey of 100 artists from across Inuit Nunangat, coupled struggling. -

English Version of the Press Release Follows Below)

Communiqué de presse (English version of the Press Release follows below) La galerie Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain a l'honneur de présenter une exposition personnelle de dessins de Napachie Pootoogook (née en 1938 à Sako Island Camp, NT, Canada ; décédée en 2002 à Kinngait (Cape Dorset), NU, Canada) provenant des archives de Dorset Fine Arts. Bien que cette sélection représente la première exposition au Québec consacrée aux dessins de Napachie Pootoogook, il y a déjà eu d'importantes expositions et publications canadiennes qui témoignent de ses contributions artistiques uniques et significatives. « Dans les dessins autobriographiques de Napachie, la perspective est si intensément personnelle qu’on y sent une culture dans la culture – un monde de femmes soutenant les hommes, et leur survivant parfois. Il y a les moments heureux des travaux et des jeux partagés pendant que les hommes sont partis chasser. Il y a les périodes difficiles et solitaires où il faut endurer des mœurs sociales qui ne laissaient souvent aucun contrôle sur des étapes aussi intimes que le mariage et l’accouchement. Bien que la souffrance soit solitaire et fréquente, la large communauté, qui, souvent, réconforte ou intervient, constitue un facteur d’équilibre. Les dessins donnent une image vivante de la vie de Napachie à travers les inscriptions syllabiques, mais aussi, de façon plus puissante encore, à travers les détails, les compositions et l’émotion exprimée dans son œuvre. Les dessins sont parsemés de détails qui offrent un portrait réaliste de la culture des Inuits du sud de l’ÎLe de Baffin, les Sikusilaarmiut : sont représentés leurs vêtements, leurs coiffures, leurs outils, leurs habitats d’été et d’hiver, ainsi que les paysages. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Discover Inuit

) DiscoverDiscover InuitInuit ArtArt What do polar bears look like when they stand up on their hind legs? What kinds of creatures are the heroes of Inuit legends? How did Inuit mothers keep their babies warm through the freezing arctic days and nights? What does an Inuit summer camp look like? What are some of the big concerns for young Inuit today? You’ll learn the answers) to all these questions, and The detail in Inuit sculpture hundreds more, through and colourful drawings will open more doors than you can imagine. the wonderful world Many of the older Inuit artists working today grew up in a traditional way. They of Inuit art. lived in igloos in winter and tents made of animal skins in summer. Their families returned to their winter and summer camps each year when the sea mammals and animals (like seals, whales and caribou), came in greatest numbers. Mothers carried their babies in an amauti — the big hood on their parkas. When the family travelled, it was on a sled pulled by a dog team. What Inuit art shows This traditional way of life is one of the big subjects in Inuit art. By showing us in drawings and sculptures how their ancestors lived, Inuit artists are keeping their history alive. Art helps them remember, and treasure, the ways their ancestors hunted and made protective clothing and shelter. In their Stories of ) art, many Inuit are making a visual history to show how their ancestors adapted to living in one of the harshest climates shamans tell on earth. -

Myth–Making and Identities Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, Vol 2

The Idea of North Myth–Making and Identities Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, vol 2. Publisher: The Birch and the Star – Finnish Perspectives on the Long 19th Century ©The Birch and the Star and the authors. All rights reserved. Editors: Frances Fowle and Marja Lahelma Designer: Vilja Achté Cover illustration: Vilja Achté Helsinki 2019 ISBN: 978-952-94-1658-5 www.birchandstar.org Contents Preface Frances Fowle and Marja Lahelma 4 Introduction: Conceptualising the North at the Fin de Siècle Frances Fowle and Marja Lahelma 5 Sámi, Indigeneity, and the Boundaries of Nordic National Romanticism Bart Pushaw 21 Photojournalism and the Canadian North: Rosemary Gilliat Eaton’s 1960 Photographs of the Eastern Canadian Arctic Danielle Siemens 34 Quaint Highlanders and the Mythic North: The Representation of Scotland in Nineteenth Century Painting John Morrison 48 The North, National Romanticism, and the Gothic Charlotte Ashby 58 Feminine Androgyny and Diagrammatic Abstraction: Science, Myth and Gender in Hilma af Klint’s Paintings Jadranka Ryle 70 Contributors 88 3 This publication has its origins in a conference session and assimilations of the North, taking into consideration Preface convened by Frances Fowle and Marja Lahelma at the issues such as mythical origins, spiritual agendas, and Association for Art History’s Annual Conference, which notions of race and nationalism, tackling also those aspects took place at the University of Edinburgh, 7–9 April 2016. of northernness that attach themselves to politically sensitive Frances Fowle and The vibrant exchange of ideas and fascinating discussions issues. We wish to extend our warmest thanks to the authors during and after the conference gave us the impetus to for their thought-provoking contributions, and to the Birch continue the project in the form of a publication. -

Hudson Bay Ice Conditions

Hudson Bay Ice Conditions ERIC W. DANIELSON, JR.l ABSTRACT.Monthly mean ice cover distributions for Hudson Bay have been derived, based upon an analysis of nine years of aerial reconnaissance and other data. Information is presented in map form, along with diseussian Of significant features. Ice break-up is seen to work southward from the western, northern, and eastern edges of the Bay; the pattern seems to be a result of local topography, cur- rents, and persistent winds. Final melting occurs in August. Freeze-up commences in October, along the northwestern shore, and proceeds southeastward. The entire Bay is ice-covered by early January,except for persistent shore leads. RÉSUMÉ. Conditions de la glace dans la mer d’Hudson. A partir de l’analyse de neuf années de reconnaissances aériennes et d’autres données, on a pu déduire des moyennes mensuelles de distribution de la glace pour la mer d’Hudson. L‘informa- tion est présentte sous formes de cartes et de discussion des Cléments significatifs. On y voit que la débâcle progresse vers le sud à partir des marges ouest, nord et est dela mer; cette séquence sembleêtre le résultat de la topographielocale, des courants et .des vents dominants. La fonte se termine en aofit. L’enge€wommence en octobre le long de la rive nord-ouest et progresse vers le sud-est. Sauf pow les chenaux côtiers persistants, la mer est entihrement gelée au début de janvier. INTRODUCTION In many respects, ice cover is a basic hydrometeorological variable. In Hudson Bay (Fig. 1) it might be considered the most basic of all, as it influences all other conditions so decisively. -

NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas Cultural Heritage and Interpretative

NTI IIBA for Phase I: Cultural Heritage Resources Conservation Areas Report Cultural Heritage Area: Dewey Soper and Interpretative Migratory Bird Sanctuary Materials Study Prepared for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 1 May 2011 This report is part of a set of studies and a database produced for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. as part of the project: NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas, Cultural Resources Inventory and Interpretative Materials Study Inquiries concerning this project and the report should be addressed to: David Kunuk Director of Implementation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 3rd Floor, Igluvut Bldg. P.O. Box 638 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 E: [email protected] T: (867) 975‐4900 Project Manager, Consulting Team: Julie Harris Contentworks Inc. 137 Second Avenue, Suite 1 Ottawa, ON K1S 2H4 Tel: (613) 730‐4059 Email: [email protected] Report Authors: Philip Goldring, Consultant: Historian and Heritage/Place Names Specialist Julie Harris, Contentworks Inc.: Heritage Specialist and Historian Nicole Brandon, Consultant: Archaeologist Note on Place Names: The current official names of places are used here except in direct quotations from historical documents. Names of places that do not have official names will appear as they are found in the source documents. Contents Maps and Photographs ................................................................................................................... 2 Information Tables .......................................................................................................................... 2 Section -

SPRING 2019 CATALOGUE Have You Heard a Good Book Lately? Nimbus Audio Is Pleased to Present Our Latest Books for Your Listening Pleasure

SPRING 2019 CATALOGUE Have you heard a good book lately? Nimbus Audio is pleased to present our latest books for your listening pleasure. They provide all the thrills, twists, and humour of the print titles that you love in an easy-to-access audio edition. Available on Audible.com, Audiobooks.com, Findaway.com, Hoopladigital.com, Kobo.com, and Overdrive.com. Coming Soon! The Blind Mechanic The Effective Citizen A Circle on the Surface Text by Marilyn Davidson Elliott Text and Narration by Text by Carol Bruneau Narrator TBA Graham Steele Narrated by Ryanne Chisholm $31.95 | History $31.95 | Politics $31.95 | Fiction 978-1-77108-512-0 978-1-77108-683-7 978-1-77108-622-6 Audiobooks Ready for a Listen! First Degree The Sea Was in Beholden Text and Narration by Their Blood Text by Lesley Crewe Kayla Hounsell Text by Quentin Casey Narrated by Stephanie Domet Narrated by Costas Halavrezos $31.95 | True Crime $31.95 | Fiction 978-1-77108-538-0 $31.95 | History 978-1-77108-537-3 978-1-77108-682-0 Truth and Honour The Fundy Vault Foul Deeds Mary, Mary Chocolate River Rescue After Many Years Text by Greg Marquis Text and Narration by Text and Narration by Text by Lesley Crewe Text by Jennifer McGrath Text by L. M. Montgomery Narrated by Costas Halavrezos Linda Moore Linda Moore Narrated by Narrated by Narrated by Elva Mai Hoover Stephanie Domet Courtney Siebring $31.95 | True Crime $31.95 | Mystery $31.95 | Mystery $31.95 | Fiction 978-1-77108-538-0 978-1-77108-537-3 978-1-77108-512-0 $31.95 | Fiction $31.95 | Children’s Fiction 978-1-77108-622-6 978-1-77108-513-7 978-1-77108-512-0 Catalogue front cover illustration courtesy of Mathilde Cinq-Mars from My Mommy, My Mama, My Brother, and Me (page 23). -

"Inuksuk: Icon of the Inuit of Nunavut"

Article "Inuksuk: Icon of the Inuit of Nunavut" Nelson Graburn Études/Inuit/Studies, vol. 28, n° 1, 2004, p. 69-82. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/012640ar DOI: 10.7202/012640ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 9 février 2017 07:10 Inuksuk: Icon of the Inuit of Nunavut Nelson Graburn* Résumé: L’inuksuk: icône des Inuit du Nunavut Les Inuit de l’Arctique canadien ont longtemps été connus par le biais des rapports écrits par les explorateurs, les baleiniers, les commerçants, ainsi que les missionnaires. Célèbres pour leurs igloos, traîneaux à chiens, kayaks et vêtements de peau, ils sont devenus les principaux «durs» de l’Arctique américain comme l’a montré le film «Nanook of the North». Maintenant qu’ils apparaissent sur la scène mondiale dotés de leurs moyens propres, leur singularité allégorique est aujourd’hui menacée. -

Arctic Community Exploration Tour August 5 - 12, 2020 Join Host Dr

Arctic Community Exploration Tour August 5 - 12, 2020 Join host Dr. Darlene Coward Wight on a Discovery Tour of Inuit Art in Canada’s Arctic Winnipeg Art Gallery Arctic Community Exploration Tour 5 – 12 August 2020 In the lead-up to the opening of the WAG Inuit Art The Winnipeg Art Gallery holds in trust more than Centre in fall 2020, this tour will be escorted by Dr. 13,000 Inuit artworks – each one with stories to tell. Darlene Coward Wight, who has been the Curator of Sharing these stories with the world is at the core of Inuit Art at the WAG since 1986. Darlene has received the WAG Inuit Art Centre project. The WAG Inuit Art a BA (Hons) in Art History and an MA in Canadian Centre will be an engaging, accessible space where Studies from Carleton University and an honorary you will experience art and artists in new ways. Doctor of Letters from the University of Manitoba in On this tour you will visit two of the main centres for 2012. She has curated over 90 exhibitions and written Inuit art, Cape Dorset and Pangnirtung. You will also 26 exhibition catalogues, as well as many smaller have a chance to meet several of the artists and publications and articles. She is also the editor and engage with them as you learn about the inspirations major contributor for the book Creation & for the tremendous art they create. Transformation: Defining Moments in Inuit Art. Inclusions: • Includes tour escort Darlene Coward Wight, Curator of Inuit Art at the WAG • Round trip airfare Ottawa – Pangnirtung – Cape Dorset – Iqaluit – Ottawa • One-night accommodation Hilton Garden Inn Ottawa Airport • Two nights accommodation Auyuittuq Lodge Pangnirtung, with full board • Two nights accommodation Cape Dorset Suites, with full board • Two nights accommodation Frobisher Inn Iqaluit (no meals included) Exclusions: • Boating excursion to Auyuittuq National Park (duration approx. -

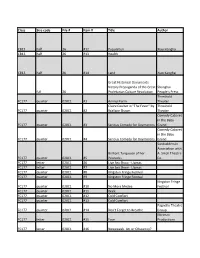

Drawer Inventory Combined G

Class Size code File # Item # Title Author CB13 half 26 #12 Population Xiao Hangha CB13 half 26 #13 Health CB13 half 26 #14 Land Xiao Kanghai Great Historical Documents - Victory Propaganda of the Great Shanghai full 26 Proletarian Culture Revolution People's Press Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #1 Animal Farm Theater Claire Coulter in "The Fever" by Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #2 Wallace Shawn Theater Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #3 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #4 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Sunbuilders in Association with Brilliant Turquoise of her A. Small Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #5 Peacocks Co. FC177 letter 020C1 #6 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 letter 020C1 #7 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 quarter 020C1 #8 Kingston Fringe Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #9 Kingston Fringe Festival Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #10 No More Medea Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #11 Walk FC177 quarter 020C1 #12 Cold Comfort FC177 quarter 020C1 #13 Cold Comfort Pagnello Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #14 Don't Forget to Breathe Group Mirimax FC177 letter 020C1 #15 Face Productions FC177 letter 020C1 #16 Newsweek. Art or Obscenity? Month of Sundays, Broadway Bound, A Night at the Grand, Baby Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #17 Sex and Politics Theatre Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #18 Shaking Like a Leaf FC177 quarter 020C1 #19 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #20 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #21 Kennedy's Children FC177 quarter 020C1 #22 Dumbwaiter/Suppress FC177 letter 020C1 #23 Bath Haydon Theatre Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #24 Using Festival West of Eden FC177 quarter 020C1 #25 Big Girls Don't Cry Production Two One Act Plays: "Winners" A.