CFB's Comprehensive Report on the 2017 Citywide Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the News – State Governor Breaks Ground on New Belmont Park Arena

This Week In New York/Page 1 This Week in New York Covering New York State and City Government A Publication of Pitta Bishop & Del Giorno LLC September 27, 2019 Edition Shanah Tovah from Pitta Bishop & Del Giorno LLC In the News – State Governor Breaks Ground on New Belmont Park Arena Governor Andrew Cuomo joined the New York Islanders, National Hockey League Commissioner Gary Bettman, local leaders and hockey fans to break ground on the New York Islanders' new arena at Belmont Park, the centerpiece of the $1.3 billion Belmont Park Redevelopment. In addition, Governor Cuomo announced the team has agreed to play 28 regular season games at the Nassau Veteran's Memorial Coliseum during the 2019-2020 season, seven more than previously planned. {00665744.DOCX / }Pitta Bishop & Del Giorno LLC, 111 Washington Avenue, Albany, New York. (518) 449-3320 Theresa Cosgrove, editor, [email protected] This Week In New York/Page 2 "The Islanders belong on Long Island — and today we start building the state-of-the-art home this team and their fans deserve while generating thousands of jobs and billions in economic activity for the region's economy," Governor Cuomo said. "With seven more Islanders games at the Coliseum this season, fans will have even more opportunities to see their favorite team and generate momentum for the move to their new home in two years. At the end of the day this project is about building on two great Long Island traditions - Belmont Park and the Islanders - and making them greater than ever." Announced in December 2017, the Belmont Redevelopment Project will turn 43 acres of underutilized parking lots at Belmont Park into a premier sports and hospitality destination, including a new 19,000-seat arena for the New York Islanders hockey team and other events, a 250-key hotel, a retail village and office and community space. -

Examining Turnover in the New York State Legislature: 2009-2010 Update," Feb 2011

A Report of Citizens Union of the City of New York EXAMINING TURNOVER IN THE NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATURE: 2009 – 2010 Update Research and Policy Analysis by Citizens Union Foundation Written and Published by Citizens Union FEBRUARY 2011 Endorsed By: Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law Common Cause NY League of Women Voters of New York State New York Public Interest Research Group Citizens Union of the City of New York 299 Broadway, Suite 700 New York, NY 10007-1976 phone 212-227-0342 • fax 212-227-0345 • [email protected] • www.citizensunion.org www.gothamgazette.com Peter J.W. Sherwin, Chair • Dick Dadey, Executive Director TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary Page 1 II. Introduction and Methodology Page 3 III. Acknowledgments Page 5 IV. Major Findings on Legislative Turnover, 2009-2010 Page 6 V. Findings on the Causes of Turnover, 1999-2010 Page 8 VI. Opportunities for Reform Page 16 VII. Appendices A. Percentage of Seats Turned Over in the New York State Legislature, 1999-2010 B. Causes of Turnover by Percentage of Total Turnover, 1999-2010 C. Total Causes of Turnover, 1999-2010 D. Ethical and Criminal Issues Resulting in Turnover, 1999-2010 E. Ethical and Criminal Issues Resulting in Turnover Accelerates: Triples in Most Recent 6-Year Period F. Table of Individual Legislators Who Have Left Due to Ethical or Criminal Issues, 1999-2010 G. Table of Causes of Turnover in Individual Assembly and Senate Districts, 2009 – 2010 Citizens Union Examining Legislative Turnover: 2009 - 2010 Update February 2011 Page 1 I. Executive Summary The New York State Legislature looked far different in January 2011 than it did in January 2009, as there were 47 fresh faces out of 212, when the new legislative session began compared to two years ago. -

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017 NEW YORK LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS nylcv.org/nycscorecard INTRODUCTION Each year, the New York League of Conservation Voters improve energy efficiency, and to better prepare the lays out a policy agenda for New York City, with goals city for severe weather. we expect the Mayor and NYC Council to accomplish over the course of the proceeding year. Our primary Last month, Corey Johnson was selected by his tool for holding council members accountable for colleagues as her successor. Over the years he has progress on these goals year after year is our annual been an effective advocate in the fight against climate New York City Council Environmental Scorecard. change and in protecting the health of our most vulnerable. In particular, we appreciate his efforts In consultation with over forty respected as the lead sponsor on legislation to require the environmental, public health, transportation, parks, Department of Mental Health and Hygiene to conduct and environmental justice organizations, we released an annual community air quality survey, an important a list of eleven bills that would be scored in early tool in identifying the sources of air pollution -- such December. A handful of our selections reward council as building emissions or truck traffic -- particularly members for positive votes on the most significant in environmental justice communities. Based on this environmental legislation of the previous year. record and after he earned a perfect 100 on our City The remainder of the scored bills require council Council Scorecard in each year of his first term, NYLCV members to take a public position on a number of our was proud to endorse him for re-election last year. -

NYC Council District 45 (Flatbush, East Flatbush, Flatlands, Midwood, Canarsie)

NYC Council District 45 (Flatbush, East Flatbush, Flatlands, Midwood, Canarsie) Monique Chandler-Waterman P. 3 Farah Louis P. 9 Xamayla Rose P. 15 Anthony Beckford * P. 21 * Anthony Beckford is no longer running in the May 14, 2019 Special Election and will not appear on the ballot. NYC Council District 45 Special Election Questionnaire About Us Launched in 2017, Voters For Animal Rights (VFAR) is a New York based 501c(4) grassroots multi-issue animal advocacy organization that is building political power for animals. Our mission is to elect candidates who support animal protection, lobby for stronger laws to stop animal cruelty, and hold elected officials accountable to humane voters. VFAR mobilizes public concern for animals through the political process. We know that animal protection is not only a moral issue but a bi-partisan political issue as well. Over 90% of Americans believe that animals need protection from abuse and exploitation. To that end, we organize humane voters to support candidates that care about animals. If you support animals, then we want to support you! There are over 60,000 humane voters throughout New York state, hundreds of which are volunteers for VFAR who are ready to knock on doors, make phone calls and get out the vote to elect people that will stand up for animals. We deliver the vote – for the animals and for you. As an example, here is our animal-friendly voter guide from the NYC Special Election for Public Advocate. Endorsement Process Candidates seeking our endorsement for the NYC Council District 45 Special Election are required to fill out this questionnaire and submit to [email protected] by Friday, April 26. -

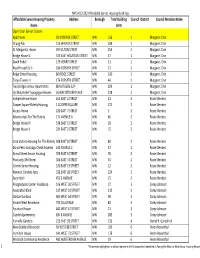

Master 202 Property Profile with Council Member District Final For

NYC HUD 202 Affordable Senior Housing Buildings Affordable Senior Housing Property Address Borough Total Building Council District Council Member Name Name Units Open Door Senior Citizens Apartment 50 NORFOLK STREET MN 156 1 Margaret Chin Chung Pak 125 WALKER STREET MN 104 1 Margaret Chin St. Margarets House 49 FULTON STREET MN 254 1 Margaret Chin Bridge House VI 323 EAST HOUSTON STREET MN 17 1 Margaret Chin David Podell 179 HENRY STREET MN 51 1 Margaret Chin Nysd Forsyth St Ii 184 FORSYTH STREET MN 21 1 Margaret Chin Ridge Street Housing 80 RIDGE STREET MN 100 1 Margaret Chin Tanya Towers II 174 FORSYTH STREET MN 40 1 Margaret Chin Two Bridges Senior Apartments 80 RUTGERS SLIP MN 109 1 Margaret Chin Ujc Bialystoker Synagogue Houses 16 BIALYSTOKER PLACE MN 128 1 Margaret Chin Independence House 165 EAST 2 STREET MN 21 2 Rosie Mendez Cooper Square Elderly Housing 1 COOPER SQUARE MN 151 2 Rosie Mendez Access House 220 EAST 7 STREET MN 5 2 Rosie Mendez Alliance Apts For The Elderly 174 AVENUE A MN 46 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House IV 538 EAST 6 STREET MN 18 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House V 234 EAST 2 STREET MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Casa Victoria Housing For The Elderly 308 EAST 8 STREET MN 80 2 Rosie Mendez Dona Petra Santiago Check Address 143 AVENUE C MN 57 2 Rosie Mendez Grand Street Senior Housing 709 EAST 6 STREET MN 78 2 Rosie Mendez Positively 3Rd Street 306 EAST 3 STREET MN 53 2 Rosie Mendez Cabrini Senior Housing 220 EAST 19 STREET MN 12 2 Rosie Mendez Renwick Gardens Apts 332 EAST 28 STREET MN 224 2 Rosie Mendez Securitad I 451 3 AVENUE MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Postgraduate Center Residence 516 WEST 50 STREET MN 22 3 Corey Johnson Associated Blind 137 WEST 23 STREET MN 210 3 Corey Johnson Clinton Gardens 404 WEST 54 STREET MN 99 3 Corey Johnson Encore West Residence 755 10 AVENUE MN 85 3 Corey Johnson Fountain House 441 WEST 47 STREET MN 21 3 Corey Johnson Capitol Apartments 834 8 AVENUE MN 285 3 Corey Johnson Yorkville Gardens 225 EAST 93 STREET MN 133 4 Daniel R. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Second

10-0604-cv Monserrate, et al. v. New York State Senate, et al. 1 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS 2 3 FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT 4 5 August Term, 2009 6 7 8 (Argued: March 12, 2010 Decided: March 16, 2010) 9 10 Docket No. 10-0604-cv 11 12 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x 13 HIRAM MONSERRATE, individually and as an 14 elected official and member of the New 15 York State Senate, CELESTE RODRIGUEZ, 16 individually and as duly registered and 17 qualified voter in the New York State 18 13th Senatorial District, MICHAEL A. 19 NARDIELO, III, individually and as duly 20 registered and qualified voter in the 21 New York State 13th Senatorial District, 22 MONIFA AFIA BEY, individually and as duly 23 registered and qualified voter in the 24 New York State 13th Senatorial District, 25 NANCY TORRES, individually and as duly 26 registered and qualified voter in the 27 New York State 13th Senatorial District, 28 LORETTA HENDERSON, individually and as 29 duly registered and qualified voter in 30 the New York State 13th Senatorial 31 District, and MALIKA K. SHABAZZ, 32 individually and as duly registered and 33 qualified voter in the New York State 34 13th Senatorial District, 35 36 Plaintiffs-Appellants, 37 38 - v.- 39 40 NEW YORK STATE SENATE, MALCOLM A. SMITH, 41 in his official capacity as Temporary 42 President of the New York State Senate, 43 ANGELO J. APONTE, in his official 1 capacity as Secretary of the New York 2 State Senate, THOMAS P. DiNAPOLI, in 3 his official capacity as State 4 Comptroller of the State of New York, 5 ERIC T. -

Community Board # 4Q

COMMUNITY BOARD # 4Q Serving: Corona, Corona Heights, Elmhurst, and Newtown th 46-11 104 Street Corona, New York 11368-2882 Telephone: 718-760-3141 Fax: 718-760-5971 e-mail: [email protected] Melinda Katz Damian Vargas Borough President Chairperson Melva Miller Christian Cassagnol Deputy Borough President District Manager June 12, 2018 PUBLIC HEARING ATTENDANCE: Board Members Attending: Damian Vargas Sandra Munoz Priscilla Carrow Gurdip Singh Narula Giancarlo Castano Georgina Oliver Lucy Cerezo-Scully Alexa Ponce Chaio-Chung Chen Ashley Reed Lynda Coral Oscar Rios Erica Cruz Cristian Romero Judith D’Andrea Clara Salas Marialena Giampino Gigi Salvador Ingrid Gomez Lucy Schilero Kristin Gonzalez Malikah Shabazz Jennifer Gutierrez Gregory Spock James Lisa Dewan Tarek Salvatore Lombardo Marcello Testa Peter Manganaro Louis Walker Patricia Martin Rosa Wong Matthew McElroy Rovenia McGowan ATTENDING: Christian Cassagnol, CB4 District Manager Christina Long, CB4 Community Assistant Council Member Francisco Moya Lissette Barcia, Council Member Francisco Moya’s Office Jacqueline A. Rozado, Council Member Francisco Moya’s Office Joe Nocerino, Queens Borough Pres. Office Julian Fox Spector, Assembly Member Ari Espinal’s Office 1 Stacy Eliuk, Public Advocate Letitia James’ Office William Giron, NYC Comptroller Scott Stringer’s Office Larry Gallegos, Congressman Joseph Crowley’s Office Kathi Ko, Dept. of City Planning Phil Wong, School District 24 Community Education Council Charles Simic, NYC Community School District 24-PLF Melanie LaRocca, NYC School Construction Authority Kelly Murphy, NYC School Construction Authority Lt. Konoski, 110 Police Precinct Izaida Velcarcel, Noah’s Ark Preparatory School Ernestine McKayle Sumaiya Mumu, LaGuardia Community College Stephanie Baez, Child Center of NY D. -

Interview with Frank Watson # ISL-A-L-2012-036 Interview # 01: August 7, 2012 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Frank Watson # ISL-A-L-2012-036 Interview # 01: August 7, 2012 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 A Note to the Reader This transcript is based on an interview recorded by the ALPL Oral History Program. Readers are reminded that the interview of record is the original video or audio file, and are encouraged to listen to portions of the original recording to get a better sense of the interviewee’s personality and state of mind. The interview has been transcribed in near- verbatim format, then edited for clarity and readability, and reviewed by the interviewee. For many interviews, the ALPL Oral History Program retains substantial files with further information about the interviewee and the interview itself. Please contact us for information about accessing these materials. DePue: Today is Tuesday, August 7, 2012. My name is Mark DePue, Director of Oral History for the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. Today I’m in Greenville, Illinois with former Senator Frank Watson. Good afternoon. Watson: Mark, good afternoon. DePue: I hope this is the first of many sessions that we have. Watson: It’s hopefully not as many as Jim Edgar had (laughs). -

Public Hearings and Meetings

VOLUME CXLI NUMBER 165 TUESDAY, AUGUST 26, 2014 Price: $4.00 Health and Mental Hygiene . 3209 THE CITY RECORD TABLE OF CONTENTS Agency Chief Contracting Officer � � � � � � 3209 BILL DE BLASIO Housing Authority . 3209 Mayor PUBLIC HEARINGS AND MEETINGS Supply Management � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3209 STACEY CUMBERBATCH City Planning Commission . 3205 Housing Preservation and Development . 3209 Commissioner, Department of Citywide Administrative Services Community Board . 3206 Maintenance � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3209 ELI BLACHMAN NYC & Company . 3209 PROPERTY DISPOSITION Editor, The City Record Licensing � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3209 Citywide Administrative Services ������������� 3206 Published Monday through Friday, except Parks and Recreation ��������������������������������� 3210 legal holidays by the New York City Office of Citywide Procurement � � � � � � � � 3206 Department of Citywide Administrative Capital Projects � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3210 Services under Authority of Section 1066 of Police ����������������������������������������������������������� 3206 the New York City Charter. Revenue � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3210 Subscription $500 a year, $4.00 daily ($5.00 by PROCUREMENT Office of Payroll Administration . 3210 mail). Periodicals Postage Paid at New York, N.Y. POSTMASTER: Send address changes Administration for Children’s Services ����� 3207 Contracts and Procurement � � � � � � � � � � � 3210 to THE CITY RECORD, 1 Centre -

They Represent You Update March 2019

They Represent You Update March 2019 Page 4 (SS34) Alessandra Biaggi (D, WF) (CC44) Kalman Yeger (D) 1250 Waters Place, Suite 1202 4424 16th Ave. (HR14) Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D) Bronx, NY 10461 Brooklyn, NY 11204 74-09 37th Avenue, Suite 305 T: (718) 822-2049 T: (718) 853-2704 Jackson Heights, NY 11372 T: (518) 455-3595 F: (718) 853-3858 T: (202) 225-3965 F: (718) 822-2321 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Page 5 Page 10 Page 7 (CC8) Diana Ayala (D) (SS18) Julia Salazar (D) 105 East 116th St. (AD80) Nathalia Fernandez (D, I) 1068 Broadway New York, NY 10029 1126 Pelham Parkway South Brooklyn, NY 11221 T: (212) 828-9800 Bronx, NY 10461 T: (917) 370-4400 F: (212) 722-6378 T: (718) 409-0109 T: (518) 455-2177 E: [email protected] T: (518) 455-5844 F: (518) 426-6947 F: (718) 409-0431 E: [email protected] (CC13) Mark Gjonaj (D) E: [email protected] 1478 Williamsbridge Road (SS20) Zellnor Myrie (D) Bronx, NY 10461 (AD87) Karines Reyes (D, WF) E: [email protected] T: (718) 931-1721 1973 Westchester Avenue F: (718) 931-1605 Bronx, NY 10462 (SS22) Andrew Gounardes (D) E: [email protected] T: (718) 931-2620 E: [email protected] T: (518) 455-5102 (CC18) Ruben Diaz, Sr. (D) F: (718) 931-2915 (SS26) Brian Kavanagh (D, WF) 2347 Lafayette Ave F: (518) 455-3693 250 Broadway, Room 2011 Bronx, NY 10473 E: [email protected] New York, NY 10007 T: (718) 792-1140 T: (212) 298-5565 F: (718) 931-0235 Page 8 T: (518) 455-2625 E: [email protected] F: (212) 431-7836 (HR11) Max Rose (D) F: (518) 426-6956 Page 6 265 New Dorp Lane, 2nd Floor E: [email protected] Staten Island, NY 10306 (SS31) Robert Jackson (D) T: (718) 667-3313 Page 11 5030 Broadway, Suite 701 F: (718) 980-0768 New York, NY 10034 (AD46) Mathylde Frontus (D) T: (212) 544-0173 Page 9 2823 West 12 Street, Suite 1F T: (518) 455-2041 Brooklyn, NY 11224 E: [email protected] (CC41) Alicka Ampry-Samuel (D) T: (718) 266-0267 400 Rockaway Ave. -

Words and Deeds

CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS NEW YORK BUSINESS Midtown East’s biggest landlords P. 6 | NYU’s answer to Cornell Tech P. 12 | Local bakers on the rise P. 26 CRAINS NEW YORK BUSINESS® SEPTEMBER 11 - 17, 2017 | PRICE $3.00 WORDS AND DEEDS VOL. XXXIII, NO. 37 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM Candidate Bill de Blasio pledged bold changes that would benet “all New Yorkers.” Our annual Stats and the City issue examines how well Mayor de Blasio delivered on those promises PAGE 14 NEWSPAPER P001_CN_20170911.indd 1 9/8/17 4:13 PM TWO • NINETY • TWO MADISON AVENUE Owner: Exclusive Leasing Agent: CN018347.indd 1 8/31/17 12:33 PM SEPTEMBER 11 - 17, 2017 CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS FROM THE NEWSROOM | JEREMY SMERD | EDITOR IN THIS ISSUE No longer just an island 4 AGENDA 5 IN CASE YOU MISSED IT THIS WEEK MARKS the ocial opening of Cornell Tech’s 6 WHO OWNS THE BLOCK A new tool campus on Roosevelt Island and a major milestone in the could help evolution of New York’s tech sector. If you haven’t been to 7 REAL ESTATE you save 8 ASKED & ANSWERED money on the campus yet, go. (You can now get there by ferry, in addi- medical bills. tion to the F line and the tram.) 9 HEALTH CARE I was there a few weeks ago to see the rst three build- 10 VIEWPOINTS ings on the 12-acre campus, which has turned the island FEATURES into a destination. ese buildings—the House, a luxurious apartment tower for students and faculty; the Bridge, which 12 NYU’S TECH EXPANSION has spaces for both instruction and collaboration; and the 14 STATS AND THE CITY Bloomberg Center, an academic building funded in large In the six years it 24 STEERING UBER part by the former mayor—total 850,000 square feet. -

The MHNA Discount Program

Information that may be of interest...March 25, 2019 The information in this eblast is provided by The Murray Hill Neighborhood Association. We are sharing the information as a service to our members. If this notice does not interest you, please disregard it. You can also find these eblasts online in PDF (printable) format at www.murrayhillnyc.org in the News section, look for Weekly Eblasts 2018. The MHNA Discount Program Please be prepared to show proof of membership when you ask for a discount. New Zumba Classes led by Talin Avakian on Thursday evenings at 7:30pm at the Armenian Evangelical Church, 152 East 34th Street (between Lexington & 3rd Avenue), First class free/$10 per class, group rates available, contact Talin at [email protected]. Changed Shelburne Hotel, 303 Lexington Avenue (37th Street), for online reservations visit www.affinia.com/shelburne select Rate Preference "Best Available" and use Promo Code NEIGH for up to 20% off. Please show proof of membership when checking in. Full list of discounts offered to MHNA members: Restaurant and Food Discounts General Discounts For Murray Hill street closures, see Traffic Updates on www.murrayhillnyc.org. If you would like to join a committee, please send an email to [email protected]. Information about the MHNA committees can be found on www.murrayhillnyc.org. Click About > Committees. Shop amazon.com via this link, and support The Murray Hill Neighborhood Association! Read our Privacy Statement Murray Hill Photo Album New Citibike stand on Lexington Avenue, corner of 36th Street. I have not seen more than 2 bikes at this stand.