The Road to the Cinephiles’ Heaven Recovered and Restored

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Releases Watch Jul Series Highlights

SERIES HIGHLIGHTS THE DARK MUSICALS OF ERIC ROHMER’S BOB FOSSE SIX MORAL TALES From 1969-1979, the master choreographer Eric Rohmer made intellectual fi lms on the and dancer Bob Fosse directed three musical canvas of human experience. These are deeply dramas that eschewed the optimism of the felt and considered stories about the lives of Hollywood golden era musicals, fi lms that everyday people, which are captivating in their had deeply infl uenced him. With his own character’s introspection, passion, delusions, feature fi lm work, Fossae embraced a grittier mistakes and grace. His moral tales, a aesthetic, and explore the dark side of artistic collection of fi lms made over a decade between drive and the corrupting power of money the early 1960s and 1970s, elicits one of the and stardom. Fosse’s decidedly grim outlook, most essential human desires, to love and be paired with his brilliance as a director and loved. Bound in myriad other concerns, and choreographer, lent a strange beauty and ultimately, choices, the essential is never so mystery to his marvelous dark musicals. simple. Endlessly infl uential on the fi lmmakers austinfi lm.org austinfi 512.322.0145 78723 TX Austin, Street 51 1901 East This series includes SWEET CHARITY, This series includes SUZANNE’S CAREER, that followed him, Rohmer is a fi lmmaker to CABARET, and ALL THAT JAZZ. THE BAKERY GIRL OF MONCEAU, THE discover and return to over and over again. COLLECTIONEUSE, MY NIGHT AT MAUD’S, CLAIRE’S KNEE, and LOVE IN THE AFTERNOON. CINEMA SÉANCE ESSENTIAL CINEMA: Filmmakers have long recognized that cinema BETTE & JOAN is a doorway to the metaphysical, and that the Though they shared a profession and were immersive nature of the medium can bring us contemporaries, Bette Davis and Joan closer to the spiritual realm. -

PARAMOUNT PICTURES: 75 YEARS July 10, 1987 - January 4, 1988

The Museum Of Modem Art For Immediate Release June 1987 PARAMOUNT PICTURES: 75 YEARS July 10, 1987 - January 4, 1988 Marlene Dietrich, William Holden, Barbara Stanwyck, Fred MacMurray, and Mae West are among the stars featured in the exhibition PARAMOUNT PICTURES: 75 YEARS, which opens at The Museum of Modern Art on July 10. The series includes films by such directors as Cecil B. De Mille, Ernst Lubitsch, Francis Coppola, Josef von Sternberg, and Preston Sturges. More than 100 films and an accompanying display of film-still enlargements and original posters trace the seventy-five year history of Paramount through the silent and sound eras. The exhibition begins on Friday, July 10, at 6:00 p.m. with Dorothy Arzner's The Wild Party (1929), madcap silent star Clara Bow's first sound feature, costarring Fredric March. At 2:30 p.m. on the same day, Ernst Lubitsch's ribald musical comedy The Smiling Lieutenant (1931) will be screened, featuring Paramount contract stars Maurice Chevalier, Claudette Colbert, and Miriam Hopkins. Comprised of both familiar classics and obscure features, the series continues in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters through January 4, 1988. Paramount Pictures was founded in 1912 by Adolph Zukor, and its first release was the silent Queen Elizabeth, starring Sarah Bernhardt. Among the silent films included in PARAMOUNT PICTURES: 75 YEARS are De Mille's The Squaw Man (1913), The Cheat (1915), and The Ten Commandments (1923); von Sternberg's The Docks of New York (1928), and Erich von Stroheim's The Wedding March (1928). - more - ll West 53 Street. -

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

The Fortian 1962 the Fortian

LI/ N t THE FORTIAN 1962 THE FORTIAN The Magazine of Fort Street Boys' High School, Petersham, N.S.W. "THE FORTIAN" COMMITTEE Master in Charge of Magazine: Mr. P. P. Steinmetz. Master in Charge of Student Contributions: Mr. W. I. D. Hayward. Committee: P. Wright, R. A. Smith, J. Scott, G. Toister, R. Speiser, G. Stokes, R. Ayling, G. Cupit, P. Knight, G. Halmagyi, A. Cununine. Registered at the General Post Office, Sydney, for transmission by post as a periodical. DECEMBER, 1962 VOLUME 60 2 THE FORTIAN CONTENTS Headmaster's Message 3 Letter from Mr. P. Cork 37 School Officers, 1962 5 Letter from Mr. D. Condon 39 Editorial 6 A School Day at Munich 39 Captain's Message 7 Famous Fortians 44 1961 L.C. Results 9 Contributions 50 Induction of Prefects 14 Sportsmaster's Report 69 Portrait of John Farrow 15 Athletics 70 Library Report 17 House Reports 73 Music Report 19 Cricket 74 Debating Report . 23 Rugby Union 79 P. & C. Association 27 Soccer 83 Cadet Report 29 Tennis 87 Father and Son Evening 29 Basketball 89 Ladies' Committee 32 Water Polo 91 I.S.C.F. Report 32 Swimming 92 O.B.U. Report 35 Class Lists 97 THE FORTIAN 3 and, though its implications are not yet fully apparent, the general pattern has been de- termined and parents, pupils and teachers must all adjust themselves to the new cir- cumstances. The new system provides for a "School Certificate" at the end of four years and a "Higher School Certificate" after six years, especially for those who intend to proceed to some form of tertiary education, Parents must then decide whether their boy or girl will leave at the end of three years (provision has been made for the continuance of an "Intermediate" Certificate) or four years or continue for one or two years after the School Certificate. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23Rd, 2019

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23rd, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 24th ANNUAL NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FEATURE FILM LINEUP DANNY BOYLE’S YESTERDAY TO OPEN FESTIVAL ALEX HOLMES’ MAIDEN TO CLOSE FESTIVAL LULU WANG’S THE FAREWELL TO SCREEN AS CENTERPIECE DISNEY•PIXAR’S TOY STORY 4 PRESENTED AS OPENING FAMILY FILM IMAGES AVAILABLE HERE New York, NY (April 23, 2019) – The Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) proudly announced its feature film lineup today. The opening night selection for its 2019 festival is Universal Pictures’ YESTERDAY, a Working Title production written by Oscar nominee Richard Curtis (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, and Notting Hill) from a story by Jack Barth and Richard Curtis, and directed by Academy Award® winner Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire, Trainspotting, 28 Days Later). The film tells the story of Jack Malik (Himesh Patel), a struggling singer-songwriter in a tiny English seaside town who wakes up after a freak accident to discover that The Beatles have never existed, and only he remembers their songs. Sony Pictures Classics’ MAIDEN, directed by Alex Holmes, will close the festival. This immersive documentary recounts the thrilling story of Tracy Edwards, a 24-year-old charter boat cook who became the skipper of the first ever all-female crew to enter the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race. The 24th Nantucket Film Festival runs June 19-24, 2019, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema. A24’s THE FAREWELL, written and directed by Lulu Wang, will screen as the festival’s Centerpiece film. -

1 Small Wonder Philip Horne DOWNSIZING

1 Small Wonder Philip Horne DOWNSIZING [February 2018, Sight & Sound] There has been a long and somewhat anxious wait among admirers of Alexander Payne’s films since Nebraska in 2013 – a bleak, beautiful, drily funny picture of the post-industrial Midwest and sad, haunted lives. Four years later Payne, who still lives in his native Omaha, has come out with a grand, astonishingly daring movie – a satirical fable, or blackly comic science fiction epic, or unexpected love story. As it goes on, there’s a serious, even tragic side to the film, but its main premise is treated with such inventiveness both visual and verbal that we get constant jolts of pleasure at the imaginative scope of its makers’ conceptions. The absurd technology that scientists concerned with ‘Human Scale and Sustainability’ and climate change develop for reducing the size of the human population – by making them five inches high – is in effect like a giant microwave: it even pings when the transformation is complete. It’s deliberately low-tech. The process, invented by idealistic Norwegians to produce a ‘self- sustainable community of the small’, is imagined being then commercialised and normalised in familiar ways by global/American capitalism, sold to punters as a time-share-like ‘heaven’ called ‘Leisureland’, which is ‘like winning the lottery every day’. This because a modest nest-egg of $152,000 when transferred (unshrunk) to its newly-tiny owner’s account in a ‘small city’ translates as the equivalent of $22,5000,000: it’s an American dream. The script is full of delicious size jokes, as downsizing becomes absorbed into idiom and things get re-scaled, so that we see ‘the first small baby ever born’. -

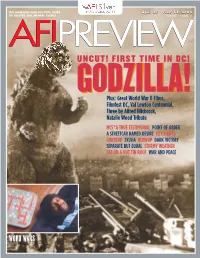

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

JOY ZAPATA Hair Dept

JOY ZAPATA Hair Dept. Head/ Hair Stylist www.joyzapatahair.com IATSE local #706, AMPAS Joy’s first break came from working at the AFI for actress Lee Grant who was directing her first student film “The Stronger”. Joy donated her time and talent to bring this period film to life for the characters who were cast. It also led Lee Grant to win her second Oscar, this time in directing, for Best Student Film. Joy went on to work for Lee on Airport 77 and over the next two decades Joy worked with some of the biggest stars in film and television as Department Head or as Personal request including Personal for Jack Nicholson for over twenty years. Joy has earned five Emmy nominations, two wins and multiple other awards. Joy’s support and dedication to her craft is only surpassed by her contagious energy on set. Highly respected, her expertise in every facet of hairstyling has given her the ability to run large departments smoothly and make her a dependable leader. Feature Films (Partial List, DEPT. HEAD unless otherwise specified); Production Director/ Producer /Production Company RICHARD JEWELL Clint Eastwood / Leonardo DiCaprio / Warner Bros. A STAR IS BORN (Key hair) Bradley Cooper / Bill Gerber / Warner Bros 8 Academy Award Nominations including Best Picture SNATCHED (AKA Amy Schumer/Goldie Hawn 2016) Jonathan Levine / Peter Chernin / Fox MOHAVE (Oscar Isaac, Garrett Hedlund) William Monahan / Aaron Ginsberg / Atlas RIDE (Department Head) Helen Hunt / Matthew Carnahan / Sandbar NEIGHBORS Nicholas Stoller / Evan Goldberg / Universal NIGHTCRAWLER (Key hair) Dan Gilroy / Jake Gyllenhaal / Bold Films THE ARTIST (Key hair) Michael Hazanavicius /T. -

Montana Kaimin, January 23, 1959 Associated Students of Montana State University

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 1-23-1959 Montana Kaimin, January 23, 1959 Associated Students of Montana State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of Montana State University, "Montana Kaimin, January 23, 1959" (1959). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 3476. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/3476 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MONTANA KAIMIN AN INDEPENDENT DAILY NEWSPAPER \ Vol. t.vttt No. 49 Montana State University, Missoula, Montana Friday, January 23,1959 43 Straight-A Students Are Pantzer Says MSU’s History to Be Topic Campus Chapel On Fall Quota Honor Roll Of LA Club’s First Meeting Straight A averages were earned by 43 students fall quarter, Still Planned J. W . Smurr, history and political science instructor, will according to Registrar Leo Smith. Students on the fall quarter Executive Vice President Robert speak on “The History of the University” at the Liberal Arts Pantzer said yesterday that the Club’s first meeting of the year, Monday at 7:30 p.m. in L A 104. honor roll numbered 388. Endowment Foundation will con To be eligible for the honor roll, a student must have either tinue its plans to build a religious Smurr’s talk, to be followed by discussion, is intended as an a minimum of 54 grade points with an index of 3 or a minimum center here. -

P36-37 Layout 1

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 2016 MUSIC & MOVIES Egyptian actress Yousra aims to raise Mideast AIDS awareness In this Sunday, Jan gyptian film star Yousra has taken up a role Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Yemen, and parts of with the United Nations to help combat Somalia, and criminalized in most of the other 31, 2016 photo, EHIV and AIDS in the Middle East, where states in the region. Drug use is also punishable Egyptian film star prevalence is low but growing rapidly. In an by death in several countries. HIV epidemics are Yousra speaks interview Monday in the Egyptian capital, Cairo, concentrated among high-risk groups - people after being where she was named a UN Goodwill who inject drugs, migrants, sex workers and appointed as UN Ambassador for the cause, she said that stigmas men who have sex with men. Goodwill and taboos associated with the virus must be Ambassador in combated and societies taught to be more sym- Antiretroviral therapy Middle East and pathetic to those infected. “For us to defeat it we Yousra, whose career spans four decades and North Africa have to admit it exists,” she told the Associated who has worked with celebrated filmmaker during a ceremony Press. “Because people have a right to medica- Yousef Chahine and actor Adel Emam, says she in Cairo. Yousra tion so they can live with dignity, and so preg- took up the cause after meeting people who has taken up a role nant woman can prevent passing it on to their had been abandoned by their families after with the United children. -

Visit Imdb.Com for Up-To-The-Minute Academy Award Updates, and View

NOMINEES FOR THE 84th ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS Best Motion Picture of the Year Best Animated Feature Film Best Achievement in Sound Mixing The Artist (2011): Thomas Langmann of the Year The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011): David Parker, The Descendants (2011): Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, A Cat in Paris (2010): Alain Gagnol, Jean-Loup Felicioli Michael Semanick, Ren Klyce, Bo Persson Jim Taylor Chico & Rita (2010): Fernando Trueba, Javier Mariscal Hugo (2011/II): Tom Fleischman, John Midgley Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2011): Scott Rudin Kung Fu Panda 2 (2011): Jennifer Yuh Moneyball (2011): Deb Adair, Ron Bochar, The Help (2011): Brunson Green, Chris Columbus, Puss in Boots (2011): Chris Miller David Giammarco, Ed Novick Michael Barnathan Rango (2011): Gore Verbinski Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011): Greg P. Russell, Hugo (2011/II): Graham King, Martin Scorsese Gary Summers, Jeffrey J. Haboush, Peter J. Devlin Midnight in Paris (2011): Letty Aronson, Best Foreign Language Film War Horse (2011): Gary Rydstrom, Andy Nelson, Tom Stephen Tenenbaum of the Year Johnson, Stuart Wilson Moneyball (2011): Michael De Luca, Rachael Horovitz, Bullhead (2011): Michael R. Roskam(Belgium) Best Achievement in Sound Editing Brad Pitt Footnote (2011): Joseph Cedar(Israel) The Tree of Life (2011): Nominees to be determined In Darkness (2011): Agnieszka Holland(Poland) Drive (2011): Lon Bender, Victor Ray Ennis War Horse (2011): Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy Monsieur Lazhar (2011): Philippe Falardeau(Canada) The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo