1. a Case for Sf and Speculative Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epistemic Value of Speculative Fiction JOHAN DE SMEDT and HELEN DE CRUZ

bs_bs_banner MIDWEST STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY Midwest Studies In Philosophy, XXXIX (2015) The Epistemic Value of Speculative Fiction JOHAN DE SMEDT and HELEN DE CRUZ 1. STORYTELLING AND PHILOSOPHIZING In Daniel F. Galouye’s novel Simulacron-3 (1964), a team of computer scientists employs an elaborate computer simulation to reduce the need for marketing research in the actual world.The agents in the simulation are conscious and do not realize they live in a simulated world. When Morton Lynch, one of the scientists, mysteriously disappears, his colleague Douglas Hall attempts to find out what happened to him, only to realize that nobody else even remembers the vanished man. Gradually, it transpires that the world Hall inhabits is also a simulation, and thus that their creation is a simulation within a simulation. The fact that Hall remembers Lynch is a computer glitch. The novel explores several philosophical topics: If the creator of a simulated world turns out to be a malicious sadist (as is the case in the novel), can he be considered a god to his creation? Do simulated beings have souls? If there is an afterlife, will only “real” people go there, or also simulated beings? Can you fall in love with a simulated being? How do people from the level above know they are living in the real physical world, or do they perhaps also inhabit a simulation? Schwitzgebel and Bakker (2013) explore similar issues in their short story Reinstalling Eden, focusing on the moral responsibilities of creators of simulations to their simulated entities. Nick Bostrom (2003), in his philosophical paper “Are We Living in a Com- puter Simulation?,” uses a weak indifference principle and probability calculus to argue that it is either highly likely that we are living in a computer simulation, or that future generations will never run any simulations (for instance, because they © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

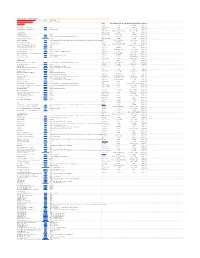

THANKSGIVING and BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always Do a Price Comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes

THANKSGIVING AND BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always do a price comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes KOHL's Coupon Codes: $15SAVEBIG15 Kohl's Cash 15% for everyoff through $50 spent 11/24 through 11/25 Electronics Store Thanksgiving Day Store HoursBlack Friday Store Hours Confirmed DVD PLAYERS AAFES Closed 4:00 AM Projected RCA 10" Dual Screen Portable DVD Player Walmart $59.00 Ace Hardware Open Open Confirmed Sylvania 7" Dual-Screen Portable DVD Player Shopko $49.99 Doorbuster Apple Closed 8 am to 10 pm Projected Babies"R"Us 5 pm to 11 pm on Friday Closes at 11 pm Projected BLU-RAY PLAYERS Barnes & Noble Closed Open Confirmed LG 4K Blu-Ray Disc Player Walmart $99.00 Bass Pro Shops 8 am to 6 pm 5:00 AM Confirmed LG 4K Ultra HD 3D Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $99.99 Deals online 11/24 at 12:01am, Doors open at 5pm; Only at Best Buy Bealls 6 pm to 11 pm 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed LG 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray Player - Model UP870 Dell Home & Home Office$109.99 Bed Bath & Beyond Closed 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung 4K Blu-Ray Player Kohl's $129.99 Shop Doorbusters online at 12:01 a.m. (CT) Thursday 11/23, and in store Thursday at 5 p.m.* + Get $15 in Kohl's Cash for every $50 SpentBelk 4 pm to 1 am Friday 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed Samsung 4K Ultra Blu-Ray Player Shopko $169.99 Doorbuster Best Buy 5:00 PM 8:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Blu-Ray Player with Built-In WiFi BJ's $44.99 Save 11/17-11/27 Big Lots 7 am to 12 am (midnight) 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Streaming 3K Ultra HD Wired Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $127.99 BJ's Wholesale Club Closed 7 am -

European Commission

6.1.2021 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Uni on C 4/1 II (Information) INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION COMMON CATALOGUE OF VARIETIES OF AGRICULTURAL PLANT SPECIES Supplement 2021/1 (Text with EEA relevance) (2021/C 4/01) CONTENTS Page Legend . 3 List of agricultural species . 4 I. Beet 1. Beta vulgaris L. Sugar beet . 4 2. Beta vulgaris L. Fodder beet . 6 II. Fodder plants 5. Agrostis stolonifera L. Creeping bent . 8 6. Agrostis capillaris L. Brown top . 8 12. Dactylis glomerata L. Cocksfoot . 8 13. Festuca arundinacea Schreber Tall fescue . 8 15. Festuca ovina L. Sheep's fescue . 8 17. Festuca rubra L. Red fescue . 9 19. ×Festulolium Asch. et Graebn. Hybrids resulting from the crossing of a species of the genus Festuca with a species of the genus Lolium . 9 20. Lolium multiflorum Lam. Italian ryegrass (including Westerwold ryegrass) . 9 20.1. Ssp. alternativum . 9 20.2. Ssp. non alternativum . 9 21. Lolium perenne L. Perennial ryegrass . 10 22. Lolium x hybridum Hausskn. Hybrid ryegrass . 15 25. Phleum pratense L. Timothy . 15 29. Poa pratensis L. Smooth-stalked meadowgrass . 16 36. Lotus corniculatus L. Birdsfoot trefoil . 16 C 4/2 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union 6.1.2021 Page 37. Lupinus albus L. White lupin . 16 54. Pisum sativum L. (partim) Field pea . 16 63. Trifolium pratense L. Red clover . 18 64. Trifolium repens L. White clover . 18 71. Vicia faba L. (partim) Field bean . 19 73. Vicia sativa L. Common vetch . 20 75. -

An Exploration of Afro-Southern Speculative Fiction

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2020 Post-Soul Speculation: An Exploration Of Afro-Southern Speculative Fiction Hilary Word Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Recommended Citation Word, Hilary, "Post-Soul Speculation: An Exploration Of Afro-Southern Speculative Fiction" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1817. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1817 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-SOUL SPECULATION: AN EXPLORATION OF AFRO-SOUTHERN SPECULATIVE FICTION A Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by HILARY M. WORD May 2020 Copyright © Hilary M. Word 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of female authored, post-soul, Afro-Southern speculative fiction. The specific texts being examined are My Soul to Keep by Tananarive Due, Stigmata by Phyllis Alesia Perry, and Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward. Through exploration of these texts, I posit two large arguments. First, I posit that this thesis as a collective work illustrates how women-authored Afro-Southern speculative fiction based in the post-soul era embodies and champions womanist politics and praxis critical for liberation through speculative elements. Second, I assert that this thesis is demonstrative of how this particular type of fiction showcases the importance of specificity of setting and reflects other, often erased facets of African American identity and realities by centering the experiences of contemporary Black Southerners. -

I PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM and the POSSIBILITIES

i PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF REPRESENTATION IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FICTION AND FILM by RACHAEL MARIBOHO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Wendy B. Faris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Kenneth Roemer Johanna Smith ii ABSTRACT: Practical Magic: Magical Realism And The Possibilities of Representation In Twenty-First Century Fiction And Film Rachael Mariboho, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Wendy B. Faris Reflecting the paradoxical nature of its title, magical realism is a complicated term to define and to apply to works of art. Some writers and critics argue that classifying texts as magical realism essentializes and exoticizes works by marginalized authors from the latter part of the twentieth-century, particularly Latin American and postcolonial writers, while others consider magical realism to be nothing more than a marketing label used by publishers. These criticisms along with conflicting definitions of the term have made classifying contemporary works that employ techniques of magical realism a challenge. My dissertation counters these criticisms by elucidating the value of magical realism as a narrative mode in the twenty-first century and underlining how magical realism has become an appealing means for representing contemporary anxieties in popular culture. To this end, I analyze how the characteristics of magical realism are used in a select group of novels and films in order to demonstrate the continued significance of the genre in modern art. I compare works from Tea Obreht and Haruki Murakami, examine the depiction of adolescent females in young adult literature, and discuss the environmental and apocalyptic anxieties portrayed in the films Beasts of the Southern Wild, Take iii Shelter, and Melancholia. -

Hellboy in the Chapel of Moloch #1 (1 Shot) Blade of the Immortal Vol. 20 (OGN) Savage #1 (4 Issues) Soulfire Shadow Magic #0 (

H M ADVS AVENGERS V.7 DIGEST collects #24-27, $9 H ULT FF V. 11 TPB H SECRET WARS OMNIBUS collects #54-57, $13 collects #1-12 & MORE, $100 H ULT X-MEN V. 19 TPB H MMW ATLAS ERA JIM V.1 HC collects #94-97, $13 collects #1-10, $60 H MARVEL ZOMBIES TPB Hellboy in the Chapel of Moloch #1 (1 shot) H MMW X-MEN V. 7 HC collects #1-5, $16 Mike Mignola (W/A) and Dave Stewart © On the heels of the second Hellboy feature collects #67-80 LOTS MORE, $55 H MIGHTY AVENGERS V. 2 TPB film, legendary artist and Hellboy creator Mike Mignola returns to the drawing table H CIVIL WAR HC collects #7-11, $25 for this standalone adventure of the world’s greatest paranormal detective! Hellboy collects #1-7 & MORE $40 H investigates an ancient chapel in Eastern Europe where an artist compelled by some- SPIDEY BND V. 1 TPB thing more sinister than any muse has sequestered himself to complete his “life’s work.” H HALO UPRISING HC collects #546-551 & MORE, $20 collects #1-4 & SPOTLIGHT, $25 H X-MEN MESSIAH COMP TPB Blade of The Immortal vol. 20 (OGN) H HULK VOL 1 RED HULK HC collects #1-13 &MORE, $30 By Hiroaki Samura. The continuing tales of Manji and Rin. This picks up after the final collects #1-6 & WOLVIE #50, $25 H ANN CONQUEST BK 1 TPB issue #131. This is the only place to get new stories! Several old teams are reunited, a H IMM IRON FIST V.3 HC collects A LOT, $25 mind-blowing battle quickly starts and races us through most of this astonishing volume, and collects #7,15,16 & MORE, $25 H YOUNG AVENGERS PRESENTS TPB an old villain finally sees some pointed retribution at the hands of one of his prisoners! Let H INC HERCULES SI HC collects #1-6, $17 the breakout battle in the "Demon Lair" begin! collects #116-120, $20 H DAREDEVIL CRUEL & UNUSUAL TP H MI ILLIAD HC collects #106-110, $15 Spawn #185 (still on-going) collects #1-8, $25 H AMERCIAN DREAM TPB story TODD McFARLANE & BRIAN HOLGUIN art WHILCE PORTACIO & TODD H MS. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin J

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement Justin J. Grandinetti James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grandinetti, Justin J., "Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement" (2015). Masters Theses. 43. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupy the Future: A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin Grandinetti A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication May 2015 Dedication Page This thesis is dedicated to the world’s revolutionaries and all the individuals working to make the planet a better place for future generations. ii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank a number of people for their assistance and support with this thesis project. First, a heartfelt thank you to my thesis chair, Dr. Jim Zimmerman, for always being there to make suggestions about my drafts, talk about ideas, and keep me on schedule. -

378954: Speculative Fiction and Magical Realism > Syllabus

378954: Speculative Fiction and Magical Realism WRITING-X 413.9E Spring 2021 Section 1 3 Credits 04/07/2021 to 06/15/2021 Modified 04/04/2021 Meeting Times New course material will be published on Wednesdays. Creative Responses are due by Tuesday, 11:59pm. Feedback and reading responses are due by Wednesday, 11:59pm. Description Reality is frequently inaccurate. Why not accurately depict that? This workshop is dedicated to kick-starting your imagination with the help of visualization and acting exercises, Oulipo writing prompts, and other creative techniques. We take a leap beyond the ordinary with examples on how to craft an engaging alternate reality, flesh out an enthralling non-human character, or dream up an unforgettable story line in space. At the end of 10 weeks, you have a better grip on how to apply creative writing techniques designed to help you think outside the box for your own speculative fiction story. Objectives 1. You will read and analyze seminal works in 21st Century American Speculative fiction by a variety of authors from different ethnicities, class, and gender, with the eye of a creator and not a reviewer. 2. You will develop the muscle of writing, build a writing practice, and participate in a literary community based on writing exercises, discussion threads, and engaging in feedback. 3. You will construct your own novums based on studying the ones in this course in order to write your own. 4. You will identify and practice craft techniques used in literary fiction such as Voice, Character, and Structure, to implement in your own work. -

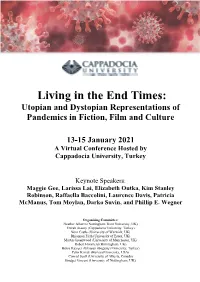

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries. -

Philosophers' Science Fiction / Speculative Fiction

Philosophers’ Science Fiction / Speculative Fiction Recommendations, Organized by Author / Director November 3, 2014 Eric Schwitzgebel In September and October, 2014, I gathered recommendations of “philosophically interesting” science fiction – or “speculative fiction” (SF), more broadly construed – from thirty-four professional philosophers and from two prominent SF authors with graduate training in philosophy. Each contributor recommended ten works of speculative fiction and wrote a brief “pitch” gesturing toward the interest of the work. Below is the list of recommendations, arranged to highlight the authors and film directors or TV shows who were most often recommended by the list contributors. I have divided the list into (A.) novels, short stories, and other printed media, vs (B.) movies, TV shows, and other non- printed media. Within each category, works are listed by author or director/show, in order of how many different contributors recommended that author or director, and then by chronological order of works for authors and directors/shows with multiple listed works. For works recommended more than once, I have included each contributor’s pitch on a separate line. The most recommended authors were: Recommended by 11 contributors: Ursula K. Le Guin Recommended by 8: Philip K. Dick Recommended by 7: Ted Chiang Greg Egan Recommended by 5: Isaac Asimov Robert A. Heinlein China Miéville Charles Stross Recommended by 4: Jorge Luis Borges Ray Bradbury P. D. James Neal Stephenson Recommended by 3: Edwin Abbott Douglas Adams Margaret