Non-Violent Popular Resistance in the West Bank: the Case of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

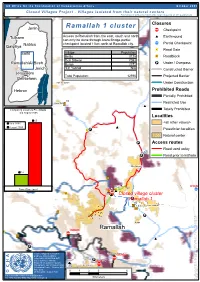

Ramallah 1 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

D UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 º¹P Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers º¹P Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) /" ## Ramallah 1 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm AccessSalfit to Ramallah from the east, south and north Earthmound can only be done through Atara Bridge partial ¬Ç Nablus checkpoint located 11km north of Ramallah city. Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya D Road## Gate Salfit Village Population Beitin 3125 /" Roadblock Deir Dibwan 7093 º¹ Ramallah/Al Bireh Burqa 2372 P Under / Overpass 'Ein Yabrud N/A ## Jericho ### Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 12590 ## Projected Barrier Bethlehem ## Deir as Sudan Deir as Sudan ## Under Construction ## Hebron Prohibited Roads C /" An Nabi Salih Partially Prohibited ¬Ç ## 15 Umm Safa/" Restricted Use ## # # Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Localities 65 Year 2000 <all other values> August 2005 Atara ## D ¬Çº¹P Palestinian localities Natural center º¹P Access routes Road used today 11 12 ##º¹P/" Road prior to Intifada 'Ein'Ein YabrudYabrud 12 /" /" 10 At Tayba /" 9 Beitin Ç Travel Time (min) DCO 2 D ¬ /"Ç## /" ¬/"3 ## 1 Closed village cluster Ramallahº¹P 1 42 /" 43 Deir Dibwan /" /" º¹P the part of the the of part the Burqa Ramallah delimitation the concerning D ¬Ç Beituniya /" ## º¹DP Closure mapping is a work in Qalandiya QalandiyaCamp progress. Closure data is Ç collected by OCHA field staff º¹ ¬ Beit Duqqu and is subject to change. P Atarot 144 Maps will be updated regularly. ### ¬Ç Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian 170 Al Judeira Information Centre - October 2005 Al Jib Beit 'Anan ## Bir Nabala Base data: Al 036Jib 12 O C H A O C H OCHA updateBeit AugustIjza 2005 losedFor comments village contact <[email protected]> cluster # # Tel. -

Occupied Palestinian Territory (Including East Jerusalem)

Reporting period: 29 March - 4 April 2016 Weekly Highlights For the first week in almost six months there have been no Palestinian nor Israeli fatalities recorded. 88 Palestinians, including 18 children, were injured by Israeli forces across the oPt. The majority of injuries (76 per cent) were recorded during demonstrations marking ‘Land Day’ on 30 March, including six injured next to the perimeter fence in the Gaza Strip, followed by search and arrest operations. The latter included raids in Azzun ‘Atma (Qalqiliya) and Ya’bad (Jenin) involving property damage and the confiscation of two vehicles, and a forced entry into a school in Ras Al Amud in East Jerusalem. On 30 occasions, Israeli forces opened fire in the Access Restricted Area (ARA) at land and sea in Gaza, injuring two Palestinians as far as 350 meters from the fence. Additionally, Israeli naval forces shelled a fishing boat west of Rafah city, destroying it completely. Israeli forces continued to ban the passage of Palestinian males between 15 and 25 years old through two checkpoints controlling access to the H2 area of Hebron city. This comes in addition to other severe restrictions on Palestinian access to this area in place since October 2015. During the reporting period, Israeli forces removed the restrictions imposed last week on Beit Fajjar village (Bethlehem), which prevented most residents from exiting and entering the village. This came following a Palestinian attack on Israeli soldiers near Salfit, during which the suspected perpetrators were killed. Israeli forces also opened the western entrance to Hebron city, which connects to road 35 and to the commercial checkpoint of Tarqumiya. -

The Truth About the Struggle of the Palestinians in the 48 Regions

The truth about the struggle of the Palestinians in the 48 regions By: Wehbe Badarni – Arab Workers union – Nazareth Let's start from here. The image about the Palestinians in the 48 regions very distorted, as shown by the Israeli and Western media and, unfortunately, the .Palestinian Authority plays an important role in it. Palestinians who remained in the 48 regions after the establishment of the State of Israel, remained in the Galilee, the Triangle and the Negev in the south, there are the .majority of the Palestinian Bedouin who live in the Negev. the Palestinians in these areas became under Israeli military rule until 1966. During this period the Palestinian established national movements in the 48 regions, the most important of these movements was "ALARD" movement, which called for the establishment of a democratic secular state on the land of Palestine, the Israeli authorities imposed house arrest, imprisonment and deportation active on this national movement, especially in Nazareth town, and eventually was taken out of .the law for "security" reasons. It is true that the Palestinians in the 48 regions carried the Israeli citizenship or forced into it, but they saw themselves as an integral part of the Palestinian Arab people, are part and an integral part of the Palestinian national movement, hundreds of Palestinians youth in this region has been joined the Palestinian .resistance movements in Lebanon in the years of the sixties and seventies. it is not true that the Palestinians are "Jews and Israelis live within an oasis of democracy", and perhaps the coming years after the end of military rule in 1966 will prove that the Palestinians in these areas have paid their blood in order to preserve their Palestinian identity, in order to stay on their land . -

13-26 July 2021

13-26 July 2021 Latest developments (after the reporting period) On 28 July, Israeli forces shot and killed an 11-year-old Palestinian boy who was in a car with his father at the entrance of Beit Ummar (Hebron). According to the Israeli military, soldiers ordered a driver to stop and, after he failed to do so, they shot at the vehicle, reportedly aiming at the wheels. On 29 July, during protests at the funeral of the boy, Palestinians threw stones and Israeli forces shot live ammunition, rubber bullets and tear gas canisters, killing one Palestinian. On 27 July, Israeli forces shot and killed a 41-year-old Palestinian at the entrance of Beita (Nablus). According to the military, the man was walking towards the soldiers, holding an iron bar, and did not stop after they shot warning fire. No clashes were taking place at that time. Highlights from the reporting period Two Palestinians, including a boy, died during the reporting period after being shot by Israeli forces. Israeli forces entered An Nabi Salih (Ramallah) to carry out an arrest operation, and when Palestinian residents threw stones at them, soldiers shot live ammunition and tear gas canisters, killing a 17-year-old boy. The boy, according to the military, was throwing stones and endangered the life of soldiers, while, according to Palestinian sources, he was shot in his back. On 26 July, a Palestinian died of wounds after being shot by Israeli forces on 14 May, in Sinjil (Ramallah), during clashes between Palestinians and Israeli forces. Overall, Israeli forces injured 615 Palestinians across the West Bank, including 24 children, the youngest of whom is a three- month-old baby. -

By Erin Dyer Abstract Established in 1998, 'Holy Land Trust I

QUEST N. 5 - FOCUS Hope through Steadfastness: The Journey of ‘Holy Land Trust’ by Erin Dyer Abstract Established in 1998, ‘Holy Land Trust’ (HLT) serves to empower the Palestinian community in Bethlehem to discover its strengths and resources to confront the present and future challenges of life under occupation. The staff, through a commitment to the principles of nonviolence, seeks to mobilize the local community, regardless of religion, gender, or political affiliation, to resist oppression in all forms and build a model for the future based on justice, equality, and respect. This article places the work of HLT in the literature of nonviolent action and amid the nonviolent movement set by predecessors in the tumultuous history of Palestinian-Israeli relations. HLT programs and projects are presented to demonstrate the progression of nonviolent resistance from lofty goals to strategic empowerment. In a region so often defined by extremes, HLT embodies the Palestinian nonviolent resistance movement. Introduction - Part I: Theories of Nonviolent Action in a Palestinian Context - Part II: The Emergence of ‘Holy Land Trust’ in the Context of Palestinian Nonviolence - Part III: Active Nonviolence Today: Programs & Projects of ‘Holy Land Trust’ A. Nonviolence B. Travel and Encounter C. Non-Linear Leadership Development Program - Conclusion: The Vision of Holy Land Trust and Palestinian Nonviolence Introduction Sumud, or steadfastness, is a uniquely Palestinian strategy to resist occupation by remaining present on the land despite the continued hardships experienced in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt). In short, sumud “suggests staying put, not 182 Erin Dyer giving up on political and human rights.”1 The term gained usage after 1967 when “Sumud Funds” were created in Jordan to “make the continued presence of Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem economically possible” during rapid settlement building and Palestinian emigration.2 Sumud, transformed from a top-down strategy, is “neither new nor static. -

Master Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

Nonviolence in the context of the Palestinian resistance against the Israeli occupation ______________________________________________ A Master thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Submitted by: Annika Müller, Senator-Kraft-Strasse 12, 31515 Wunstorf Matriculation number: 2155001 Summer term 2008 1st examiner: Prof. Dr. Bonacker 2nd examiner: PD Dr. J.M. Becker I hereby declare that this Master thesis is the result of my own work. Material from the published or unpublished work of others referred to in the thesis is credited to the author in question in the text. Date Signature Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................- 1 - 2. Definitions .....................................................................................................................- 2 - 2.1 Defining nonviolence ............................................................................................- 2 - 2.2 Aims .......................................................................................................................- 3 - 2.3 Methods .................................................................................................................- 3 - 3. Historical development ................................................................................................- 4 - 3.1 Nonviolence theory and practice in the 20 th century .........................................- 5 - 4. Nonviolence -

PDF | 468.91 KB | English Version

United Nations A/76/94–E/2021/73 General Assembly Distr.: General 24 June 2021 Economic and Social Council Original: English General Assembly Economic and Social Council Seventy-sixth session Substantive session of 2021 Item 65 of the preliminary list* Agenda item 16 Permanent sovereignty of the Palestinian people in the Economic and social repercussions of the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Israeli occupation on the living conditions of Jerusalem, and of the Arab population in the occupied the Palestinian people in the Occupied Syrian Golan over their natural resources Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and the Arab population in the occupied Syrian Golan Economic and social repercussions of the Israeli occupation on the living conditions of the Palestinian people in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and of the Arab population in the occupied Syrian Golan Note by the Secretary-General** Summary In its resolution 2021/4, entitled “Economic and social repercussions of the Israeli occupation on the living conditions of the Palestinian people in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and the Arab population in the occupied Syrian Golan”, the Economic and Social Council requested the Secretary- General to submit to the General Assembly at its seventy-fifth session, through the Economic and Social Council, a report on the implementation of that resolution. The Assembly, in its resolution 75/236, entitled “Permanent sovereignty of the Palestinian people in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and of the Arab population in the occupied Syrian Golan over their natural resources”, requested the Secretary-General to submit a report to it at its seventy-sixth session. -

West Bank Situation

UNRWA West Bank Field Office UNITED NATIONS RELIEF AND WORKS AGENCY FOR PALESTINE REFUGEES IN THE NEAR EAST 21-24 May 2021 – West Bank Situation update #3 Situation From Friday, 21 May- 8 am until Monday, 24 May- 8 am, the following was reported in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem: - Eight armed incidents, two in the north, two in the centre and four in the south. - 40 confrontations, resulting in 45 Palestinian injuries, including one minor, and one Israeli injuries. - 96 Israeli detentions, including one minor and two refugees; and 2 PA detentions. - Seven incidents of settlers’ violence, including a group of settlers from Kiryat Arba, attacking a Palestine refugee family in Hebron. As outlined in the bar graph no. 1, the level of confrontations has reduced significantly with the peak trending downwards. This is reflected in both overall injury and live ammunition injury statistics: seven live ammunition injuries were reported, as occurred during demonstrations across the West Bank (3 Bethlehem; 1 An Nabi Salih: 1 Halhul: 1 Qalqiliya: 1 Beita). The number has decreased but still represents a higher figure than the annual average. Jan-April May (1-24 @ 8am) and % of Year Total Confrontations 718 729 (50%) Tear gas incidents 486 654 (57%) Armed incidents 159 305 (66%) ISF operations 2070 1051 (34%) Settler violence incidents 481 210 (30%) Jan-April May (1-21 @ 8am) and % of Year Total Injuries 674 2464 (89%) Of which LA injuries 83 (12% of total injuries) 682 (22% of total injuries) Fatalities 6 31 (86%) Of which LA fatalities 6 (100% of total fatalities) 29 (100% of total fatalities) Israeli settlers entered into al Aqsa mosque over the weekend. -

Palestinian Women: Mothers, Martyrs and Agents of Political Change

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2011 Palestinian Women: Mothers, Martyrs and Agents of Political Change Rebecca Ann Otis University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Otis, Rebecca Ann, "Palestinian Women: Mothers, Martyrs and Agents of Political Change" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 491. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/491 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Palestinian Women: Mothers, Martyrs and Agents of Political Change __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Josef Korbel School of International Studies University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Rebecca A. Otis June 2011 Advisor: Dr. Martin Rhodes ©Copyright by Rebecca A. Otis 2011 All Rights Reserved Author: Rebecca A. Otis Title: PALESTINIAN WOMEN: MOTHERS, MARTYRS AND AGENTS OF POLITICAL CHANGE Advisor: Dr. Martin Rhodes Degree Date: June 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation seeks to understand the role of women as political actors in the rise of Islamo-nationalist movement in Palestine. Using a historical and ethnographic approach, it examines the changing opportunity structures available to Palestinian women in the nationalist struggle between 1987 and 2007. -

Palestinian Nonviolent Resistance to Occupation Since 1967

FACES OF HOPE A Campaign Supporting Nonviolent Resistance and Refusal in Israel and Palestine AFSC Middle East Resource series Middle East Task Force | Fall 2005 Palestinian Nonviolent Resistance to Occupation Since 1967 alestinian nonviolent resistance to policies of occupa- tion and injustice dates back to the Ottoman (1600s- P1917) and British Mandate (1917-1948) periods. While the story of armed Palestinian resistance is known, the equally important history of nonviolent resistance is largely untold. Perhaps the best-known example of nonviolent resistance during the mandate period, when the British exercised colo- nial control over historic Palestine, is the General Strike of 1936. Called to protest against British colonial policies and the exclusion of local peoples from the governing process, the strike lasted six months, making it the longest general strike in modern history. Maintaining the strike for so many months required great cooperation and planning at the local Residents of Abu Ghosh, a village west of Jerusalem, taking the oath level. It also involved the setting up of alternative institu- of allegiance to the Arab Higher Committee, April 1936. Photo: Before tions by Palestinians to provide for economic and municipal Their Diaspora, Institute for Palestine Studies, 1984. Available at http://www. passia.org/. needs. The strike, and the actions surrounding it, ultimately encountered the dilemma that has subsequently been faced again and to invent new strategies of resistance. by many Palestinian nonviolent resistance movements: it was brutally suppressed by the British authorities, and many of The 1967 War the leaders of the strike were ultimately killed, imprisoned, During the 1967 War, Israel occupied the West Bank, or exiled.