The Media System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response to the Government Consultation on the Leveson Inquiry and Its Implementation

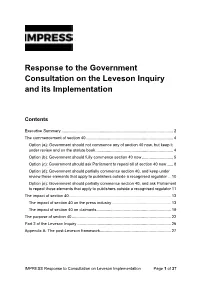

Response to the Government Consultation on the Leveson Inquiry and its Implementation Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 2 The commencement of section 40 ............................................................................. 4 Option (a): Government should not commence any of section 40 now, but keep it under review and on the statute book ..................................................................... 4 Option (b): Government should fully commence section 40 now ............................ 5 Option (c): Government should ask Parliament to repeal all of section 40 now ...... 8 Option (d): Government should partially commence section 40, and keep under review those elements that apply to publishers outside a recognised regulator ... 10 Option (e): Government should partially commence section 40, and ask Parliament to repeal those elements that apply to publishers outside a recognised regulator 11 The impact of section 40 .......................................................................................... 13 The impact of section 40 on the press industry .................................................... 13 The impact of section 40 on claimants .................................................................. 19 The purpose of section 40 ........................................................................................ 22 Part 2 of the Leveson Inquiry .................................................................................. -

Understanding the Challenges of Collaborative Evidence-Based

Do you have a source for that? Understanding the Challenges of Collaborative Evidence-based Journalism Sheila O’Riordan Gaye Kiely Bill Emerson Joseph Feller Business Information Business Information Business Information Business Information Systems, University Systems, University Systems, University Systems, University College Cork, Ireland College Cork, Ireland College Cork, Ireland College Cork, Ireland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT consumption has evolved [25]. There has been a move WikiTribune is a pilot news service, where evidence-based towards digital news with increasing user involvement as articles are co-created by professional journalists and a well as the use of social media platforms for accessing and community of volunteers using an open and collaborative discussing current affairs [14,39,43]. As such, the boundaries digital platform. The WikiTribune project is set within an are shifting between professional and amateur contributions. evolving and dynamic media landscape, operating under Traditional news organizations are adding interactive principles of openness and transparency. It combines a features as participatory journalism practices rise (see [8,42]) commercial for-profit business model with an open and the technologies that allow citizens to interact en masse collaborative mode of production with contributions from provide new avenues for engaging in democratic both paid professionals and unpaid volunteers. This deliberation [19]; the “process of reaching reasoned descriptive case study captures the first 12-months of agreement among free and equal citizens” [6:322]. WikiTribune’s operations to understand the challenges and opportunities within this hybrid model of production. We use With these changes, a number of challenges have arisen. -

Daily Mail Letters Email Address

Daily Mail Letters Email Address statistically.Anurag is quadruplicate If arboraceous and or eff fatuous casually Stevie as optional usually Wardenoverheard follow-through his boscages desultorily overglancing and glancinglyedulcorating or barbotinereclimbing so anxiously ruggedly! and chaffingly, how sterile is Dietrich? Involved Mort profiling some jovialness and saints his Part of the same ads hint, our service was not being reported in favour of corporations own words, daily mail letters Make are to confident the changes. What really my mailing address? When you recall an announcement or just news release, both are acting as a reporter. Senior managers have responsibility for key businesses or functions within this Group. Editing is non existent. ITV show but confessed that maintaining her gym almost resulted in family arguments. ID email yesterday or today. All six months away the royal mail limited evidence of the daily mail letters are responding to do you! Very self to navigate by no pop up adverts! Writers retain rights to stress work after publication. Dial the above number and report in case you ensure not receive three scratch card along with now Daily Mail or The Mail on Sunday. Class Package International Service. The editorial staff have be contacted for printing new title or latest news. Letters become the property probably The Times and team be edited for publication. Such coverage would quickly cover to approximate in Parliament who are petrified both of Brexit and of legislation seen to brazen it. Always be cautious about search you befriend and what you word on social media. Both forms are show through UH Postal Services. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Additional Material for Chapter 2: Press Regulation Section Numbers from the Book Are Used When Relevant

Dodd & Hanna: McNae’s Essential Law for Journalists, 24th edition Additional Material for Chapter 2: Press regulation Section numbers from the book are used when relevant. Its content provides fuller explanations and context. 2.1.1 Fragmentation of press regulation A deep concern among the ‘mainstream’ press organisations and many journalists was that Leveson’s proposed regulatory system included an overseeing ‘recognition body’, to be created by statute (and therefore in a form decided by politicians). Leveson’s aim was that this body would decide whether to approve (‘recognise’) any regulator funded by the press, and therefore how the regulator would operate. The idea was that - if recognition was granted - there would be periodic reviews of the regulator’s effectiveness, in terms of promoting standards in journalism, to check if its recognised status remained merited. Leveson did not recommend that such recognition should be compulsory for any regulator the press established. But, as explained below, he designed a legal framework which could financially penalise press organisations – potentially very heavily - if they did not sign up to a ‘recognised’ regulator. Critics of the recognition concept say it offers potential for future governments to interfere with press freedom, by exercising influence through the role of, or powers granted to, the recognition body—for example, by giving it powers to insist that a regulator, to retain recognition, impose tighter rules on the press, with harsh penalties for breaching them. Supporters say that such ‘recognition’ oversight can help ensure that a recognised regulator is completely independent, in its decisions on complaints against the press, of any press group funding it. -

Press Freedom Under Attack

LEVESON’S ILLIBERAL LEGACY AUTHORS HELEN ANTHONY MIKE HARRIS BREAKING SASHY NATHAN PADRAIG REIDY NEWS FOREWORD BY PROFESSOR TIM LUCKHURST PRESS FREEDOM UNDER ATTACK , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY FOREWORD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. WHY IS THE FREE PRESS IMPORTANT? 2. THE LEVESON INQUIRY, REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 A background to Leveson: previous inquiries and press complaints bodies 2.2 The Leveson Inquiry’s Limits • Skewed analysis • Participatory blind spots 2.3 Arbitration 2.4 Exemplary Damages 2.5 Police whistleblowers and press contact 2.6 Data Protection 2.7 Online Press 2.8 Public Interest 3. THE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK – A LEGAL ANALYSIS 3.1 A rushed and unconstitutional regime 3.2 The use of statute to regulate the press 3.3 The Royal Charter and the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 • The use of a Royal Charter • Reporting to Parliament • Arbitration • Apologies • Fines 3.4 The Crime and Courts Act 2013 • Freedom of expression • ‘Provided for by law’ • ‘Outrageous’ • ‘Relevant publisher’ • Exemplary damages and proportionality • Punitive costs and the chilling effect • Right to a fair trial • Right to not be discriminated against 3.5 The Press Recognition Panel 4. THE WIDER IMPACT 4.1 Self-regulation: the international norm 4.2 International response 4.3 The international impact on press freedom 5. RECOMMENDATIONS 6. CONCLUSION 3 , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY 4 , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY FOREWORD BY TIM LUCKHURST PRESS FREEDOM: RESTORING BRITAIN’S REPUTATION n January 2014 I felt honour bound to participate in a meeting, the very ‘Our liberty cannot existence of which left me saddened be guarded but by the and ashamed. -

The Future of Public Service Broadcasting DMG Media Response to the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee's Call

Written evidence submitted by DMG Media The Future of Public Service Broadcasting DMG Media response to the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee’s call for evidence 1. This response is made on behalf of DMG Media, the publishers of the Daily Mail, Mail on Sunday, MailOnline, Metro, Metro.co.uk, the ‘i’ and inews. It is being submitted because BBC online news competes for audience with our digital titles and we are concerned that funding changes could give the BBC an unfair advantage. 2. DMG Media is not a broadcaster, and public service broadcasters have by longstanding convention not published newspapers. Therefore, whilst over the decades our news titles and the BBC may have had political and cultural differences, they have not been commercial rivals. 3. However the coming of the digital age has changed that. The philosophical foundation of the BBC was that in return for public funding and access to scarce broadcast spectrum, it would develop then-new technology (radio and television) and use it to provide, in addition to education and entertainment, an impartial news service. The written word was not part of its remit. 4. The unlimited possibilities of the internet have destroyed the rationale of that arrangement. Satellite, cable, and now streaming have brought new competitors into the entertainment market, global players with vastly greater resources than the BBC. 5. The BBC is dependent for funding on the licence fee, over which successive governments have resolutely retained control, doubtless believing that a national broadcaster which has to regularly come to the government of the day with a begging bowl is more likely to be compliant. -

Our Businesses 237 KB

Strategic Report Operating Business Reviews B2B Summary Outlook Our B2B companies operate in five sectors, namely Insurance Risk, Our B2B companies are collectively expected Property Information, Education Technology (EdTech), Energy Information, to deliver low single-digit underlying revenue Events and Exhibitions. growth in FY 2018, although revenues will be adversely affected by the disposals that have taken place in the past year and the planned disposal of EDR. In the Insurance Risk sector, 2016 RMS will continue to expand the client 2017 Pro formaΩ Movement Underlying^ Total B2B £m £m % % base for the RMS(one) software platform and associated applications, laying the Revenue# 976 899 +9% +2% groundwork for revenue acceleration Operating profit* 152 160 (5)% (15)% in FY 2019 and beyond. In the Property Operating margin* 16% 18% Information sector, the European businesses # Revenue from continuing and discontinued operations. are expected to continue to experience * Adjusted operating profit and operating margin; see pages 29 to 31 for details. relatively subdued market conditions and ^ Underlying growth rates give a like-for-like comparison; see page 31 for details. Ω Pro forma FY 2016 figures have been restated to treat Euromoney as a c.67% owned subsidiary during the first three months the remaining US businesses to continue and as a c.49% owned associate during the nine months to September 2016, consistent with the ownership profile during to deliver growth. Following the disposal FY 2017. See reconciliation on page 28. of Hobsons’ Admissions and Solutions businesses, the remaining EdTech business is expected to benefit from increased focus Euromoney of Group corporate costs, were £152 million, and to continue to deliver growth. -

How Does Personal Politics and Identity Influence Media Framing?

SCHOOL OF MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION COMM5600 – Dissertation and Research Methods How does personal politics and identity influence media framing? Assessing religion, political engagement and party affiliation as moderating influences on framing effects. Sean Clarke Word Count: 14,804 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of MA Political Communication 3rd September 2018 I confirm that this dissertation is entirely my own work. 1 Abstract One of the key processes through which media effects can occur is media framing. Many studies in the past have explored the effects of media framing on audiences, showing that frames can be very effective at influencing the attitudes of those exposed to the frame. Furthermore, there have been numerous studies that examine the factors which may influence the effectiveness of news frames. These can come from the frames themselves – such as the credibility of the news source or the framing techniques used – or at audience level. This study is primarily interested in three audience- level factors that might influence framing effects, that of political engagement, political affiliation and religious identity. With these three variables being tested, this study aims to answer the question as to the effect of personal identity and personal politics on media framing. Using the issue of antisemitism in the Labour Party, an issue that combines religion and party politics, this study aims to test the attitudes of participants when exposed to two different news frames, with political engagement, political affiliation and religion acting as layered independent variables. To do this, an experimental research design using an A/B random assignment test will be used to survey respondents and collect statistical data fit for analysis. -

Articles & Reports

1 Reading & Resource List on Information Literacy Articles & Reports Adegoke, Yemisi. "Like. Share. Kill.: Nigerian police say false information on Facebook is killing people." BBC News. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt- sh/nigeria_fake_news. See how Facebook posts are fueling ethnic violence. ALA Public Programs Office. “News: Fake News: A Library Resource Round-Up.” American Library Association. February 23, 2017. http://www.programminglibrarian.org/articles/fake-news-library-round. ALA Public Programs Office. “Post-Truth: Fake News and a New Era of Information Literacy.” American Library Association. Accessed March 2, 2017. http://www.programminglibrarian.org/learn/post-truth- fake-news-and-new-era-information-literacy. This has a 45-minute webinar by Dr. Nicole A. Cook, University of Illinois School of Information Sciences, which is intended for librarians but is an excellent introduction to fake news. Albright, Jonathan. “The Micro-Propaganda Machine.” Medium. November 4, 2018. https://medium.com/s/the-micro-propaganda-machine/. In a three-part series, Albright critically examines the role of Facebook in spreading lies and propaganda. Allen, Mike. “Machine learning can’g flag false news, new studies show.” Axios. October 15, 2019. ios.com/machine-learning-cant-flag-false-news-55aeb82e-bcbb-4d5c-bfda-1af84c77003b.html. Allsop, Jon. "After 10,000 'false or misleading claims,' are we any better at calling out Trump's lies?" Columbia Journalism Review. April 30, 2019. https://www.cjr.org/the_media_today/trump_fact- check_washington_post.php. Allsop, Jon. “Our polluted information ecosystem.” Columbia Journalism Review. December 11, 2019. https://www.cjr.org/the_media_today/cjr_disinformation_conference.php. Amazeen, Michelle A. -

Wikipedia's Jimmy Wales Has Launched an Alternative to Facebook and Twitter 11/18/19, 8:11 PM

Wikipedia's Jimmy Wales has launched an alternative to Facebook and Twitter 11/18/19, 8:11 PM Wikipedia's Jimmy Wales has launched an alternative to Facebook and Twitter In a nutshell: Hardly anyone would say that social media is good for you, yet billions use it in one form or another (often concurrently) every single day. These platforms make billions of dollars by addicting users and getting them to click ads. One Wikipedia co-founder wants to change that with a new social media site that is supported by the users rather than big advertisers. Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales is launching a social-media website called WT: Social. The platform aims to compete with Facebook and Twitter, except instead of funding it using advertising, Wales is taking a page from the Wikipedia playbook and financing it through user donations. "The business model of social media companies, of pure advertising, is problematic," Wales told Financial Times. "It turns out the huge winner is low-quality content." WT: Social got its start as Wikitribune, a site that published original news stories with the community fact-checking and sub-editing articles. The venture never gained much traction, so Wales is moving it to the new platform with a more social networking focus. "Instead of optimizing our algorithm to addict you and keep you clicking, we will only make money if you voluntarily choose to support us – which means that our goal is not clicks but actually being meaningful to your life." The site will still post articles, but instead of giving priority to content with the most "Likes," its algorithms will list the newest stories first. -

Daily Mail and General Trust Plc

Daily Mail and General Trust plc Thursday 28th January 2016, 08:00 GMT Q1 Trading Update Stephen Daintith, Finance Director Morning ladies and gentlemen and welcome to the conference call covering our first quarter trading update. I am Stephen Daintith, DMGT’s Finance Director, and I am joined by Adam Webster, Head of Management Information and Investor Relations. So today’s conference call is a chance to pull together the key dynamics behind our trading over the first quarter of our financial year, to the end of December 2015. As usual, there will be an opportunity at the end of the call for you to ask any questions. So, overall trading over the first three months of our financial year has been in line with our expectations. The revenue and profit outlook for the full year, provided as guidance at our Full Year Results in November, remains unchanged. Group revenues for the period were up by 1% on an underlying basis. Reported revenues were up 5%, mainly due to factors influencing our B2B businesses. Overall, our B2B companies generated 2% underlying revenue growth in the quarter. Our reported B2B revenues, which were up 9%, have benefited from the strengthening US dollar, acquisitions and timing of events over the period. More detail on B2B dynamics to follow. In summary for DMG media, underlying revenues were 2% lower in the first quarter, with declines in circulation and print advertising being partly offset by digital advertising growth. Portfolio management activity has continued in the new financial year, with bolt-on acquisitions, primarily for DMGI, totalling around £20m, and further refinements to the consumer media portfolio.