Consciousness and the Collapse of the Wave Function

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observations of Wavefunction Collapse and the Retrospective Application of the Born Rule

Observations of wavefunction collapse and the retrospective application of the Born rule Sivapalan Chelvaniththilan Department of Physics, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka [email protected] Abstract In this paper I present a thought experiment that gives different results depending on whether or not the wavefunction collapses. Since the wavefunction does not obey the Schrodinger equation during the collapse, conservation laws are violated. This is the reason why the results are different – quantities that are conserved if the wavefunction does not collapse might change if it does. I also show that using the Born Rule to derive probabilities of states before a measurement given the state after it (rather than the other way round as it is usually used) leads to the conclusion that the memories that an observer has about making measurements of quantum systems have a significant probability of being false memories. 1. Introduction The Born Rule [1] is used to determine the probabilities of different outcomes of a measurement of a quantum system in both the Everett and Copenhagen interpretations of Quantum Mechanics. Suppose that an observer is in the state before making a measurement on a two-state particle. Let and be the two states of the particle in the basis in which the observer makes the measurement. Then if the particle is initially in the state the state of the combined system (observer + particle) can be written as In the Copenhagen interpretation [2], the state of the system after the measurement will be either with a 50% probability each, where and are the states of the observer in which he has obtained a measurement of 0 or 1 respectively. -

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit Sasu Tuohino B. Sc. Thesis Department of Physical Sciences Theoretical Physics University of Oulu 2017 Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Classical network theory4 2.1 From electromagnetic fields to circuit elements.........4 2.2 Generalized flux and charge....................6 2.3 Node variables as degrees of freedom...............7 3 Hamiltonians for electric circuits8 3.1 LC Circuit and DC voltage source................8 3.2 Cooper-Pair Box.......................... 10 3.2.1 Josephson junction.................... 10 3.2.2 Dynamics of the Cooper-pair box............. 11 3.3 Transmon qubit.......................... 12 3.3.1 Cavity resonator...................... 12 3.3.2 Shunt capacitance CB .................. 12 3.3.3 Transmon Lagrangian................... 13 3.3.4 Matrix notation in the Legendre transformation..... 14 3.3.5 Hamiltonian of transmon................. 15 4 Classical dynamics of transmon qubit 16 4.1 Equations of motion for transmon................ 16 4.1.1 Relations with voltages.................. 17 4.1.2 Shunt resistances..................... 17 4.1.3 Linearized Josephson inductance............. 18 4.1.4 Relation with currents................... 18 4.2 Control and read-out signals................... 18 4.2.1 Transmission line model.................. 18 4.2.2 Equations of motion for coupled transmission line.... 20 4.3 Quantum notation......................... 22 5 Numerical solutions for equations of motion 23 5.1 Design parameters of the transmon................ 23 5.2 Resonance shift at nonlinear regime............... 24 6 Conclusions 27 1 Abstract The focus of this thesis is on classical dynamics of a transmon qubit. First we introduce the basic concepts of the classical circuit analysis and use this knowledge to derive the Lagrangians and Hamiltonians of an LC circuit, a Cooper-pair box, and ultimately we derive Hamiltonian for a transmon qubit. -

Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics

Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics Emma Wikberg Project work, 4p Department of Physics Stockholm University 23rd March 2006 Abstract The method of Path Integrals (PI’s) was developed by Richard Feynman in the 1940’s. It offers an alternate way to look at quantum mechanics (QM), which is equivalent to the Schrödinger formulation. As will be seen in this project work, many "elementary" problems are much more difficult to solve using path integrals than ordinary quantum mechanics. The benefits of path integrals tend to appear more clearly while using quantum field theory (QFT) and perturbation theory. However, one big advantage of Feynman’s formulation is a more intuitive way to interpret the basic equations than in ordinary quantum mechanics. Here we give a basic introduction to the path integral formulation, start- ing from the well known quantum mechanics as formulated by Schrödinger. We show that the two formulations are equivalent and discuss the quantum mechanical interpretations of the theory, as well as the classical limit. We also perform some explicit calculations by solving the free particle and the harmonic oscillator problems using path integrals. The energy eigenvalues of the harmonic oscillator is found by exploiting the connection between path integrals, statistical mechanics and imaginary time. Contents 1 Introduction and Outline 2 1.1 Introduction . 2 1.2 Outline . 2 2 Path Integrals from ordinary Quantum Mechanics 4 2.1 The Schrödinger equation and time evolution . 4 2.2 The propagator . 6 3 Equivalence to the Schrödinger Equation 8 3.1 From the Schrödinger equation to PI’s . 8 3.2 From PI’s to the Schrödinger equation . -

Derivation of the Born Rule from Many-Worlds Interpretation and Probability Theory K

Derivation of the Born rule from many-worlds interpretation and probability theory K. Sugiyama1 2014/04/16 The first draft 2012/09/26 Abstract We try to derive the Born rule from the many-worlds interpretation in this paper. Although many researchers have tried to derive the Born rule (probability interpretation) from Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI), it has not resulted in the success. For this reason, derivation of the Born rule had become an important issue of MWI. We try to derive the Born rule by introducing an elementary event of probability theory to the quantum theory as a new method. We interpret the wave function as a manifold like a torus, and interpret the absolute value of the wave function as the surface area of the manifold. We put points on the surface of the manifold at a fixed interval. We interpret each point as a state that we cannot divide any more, an elementary state. We draw an arrow from any point to any point. We interpret each arrow as an event that we cannot divide any more, an elementary event. Probability is proportional to the number of elementary events, and the number of elementary events is the square of the number of elementary state. The number of elementary states is proportional to the surface area of the manifold, and the surface area of the manifold is the absolute value of the wave function. Therefore, the probability is proportional to the absolute square of the wave function. CONTENTS 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Subject .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 The importance of the subject ......................................................................................... -

Relativistic Quantum Mechanics 1

Relativistic Quantum Mechanics 1 The aim of this chapter is to introduce a relativistic formalism which can be used to describe particles and their interactions. The emphasis 1.1 SpecialRelativity 1 is given to those elements of the formalism which can be carried on 1.2 One-particle states 7 to Relativistic Quantum Fields (RQF), which underpins the theoretical 1.3 The Klein–Gordon equation 9 framework of high energy particle physics. We begin with a brief summary of special relativity, concentrating on 1.4 The Diracequation 14 4-vectors and spinors. One-particle states and their Lorentz transforma- 1.5 Gaugesymmetry 30 tions follow, leading to the Klein–Gordon and the Dirac equations for Chaptersummary 36 probability amplitudes; i.e. Relativistic Quantum Mechanics (RQM). Readers who want to get to RQM quickly, without studying its foun- dation in special relativity can skip the first sections and start reading from the section 1.3. Intrinsic problems of RQM are discussed and a region of applicability of RQM is defined. Free particle wave functions are constructed and particle interactions are described using their probability currents. A gauge symmetry is introduced to derive a particle interaction with a classical gauge field. 1.1 Special Relativity Einstein’s special relativity is a necessary and fundamental part of any Albert Einstein 1879 - 1955 formalism of particle physics. We begin with its brief summary. For a full account, refer to specialized books, for example (1) or (2). The- ory oriented students with good mathematical background might want to consult books on groups and their representations, for example (3), followed by introductory books on RQM/RQF, for example (4). -

Realism About the Wave Function

Realism about the Wave Function Eddy Keming Chen* Forthcoming in Philosophy Compass Penultimate version of June 12, 2019 Abstract A century after the discovery of quantum mechanics, the meaning of quan- tum mechanics still remains elusive. This is largely due to the puzzling nature of the wave function, the central object in quantum mechanics. If we are real- ists about quantum mechanics, how should we understand the wave function? What does it represent? What is its physical meaning? Answering these ques- tions would improve our understanding of what it means to be a realist about quantum mechanics. In this survey article, I review and compare several realist interpretations of the wave function. They fall into three categories: ontological interpretations, nomological interpretations, and the sui generis interpretation. For simplicity, I will focus on non-relativistic quantum mechanics. Keywords: quantum mechanics, wave function, quantum state of the universe, sci- entific realism, measurement problem, configuration space realism, Hilbert space realism, multi-field, spacetime state realism, laws of nature Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Background 3 2.1 The Wave Function . .3 2.2 The Quantum Measurement Problem . .6 3 Ontological Interpretations 8 3.1 A Field on a High-Dimensional Space . .8 3.2 A Multi-field on Physical Space . 10 3.3 Properties of Physical Systems . 11 3.4 A Vector in Hilbert Space . 12 *Department of Philosophy MC 0119, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr, La Jolla, CA 92093-0119. Website: www.eddykemingchen.net. Email: [email protected] 1 4 Nomological Interpretations 13 4.1 Strong Nomological Interpretations . 13 4.2 Weak Nomological Interpretations . -

Quantum Mechanics in 1-D Potentials

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 6.007 { Electromagnetic Energy: From Motors to Lasers Spring 2011 Tutorial 10: Quantum Mechanics in 1-D Potentials Quantum mechanical model of the universe, allows us describe atomic scale behavior with great accuracy|but in a way much divorced from our perception of everyday reality. Are photons, electrons, atoms best described as particles or waves? Simultaneous wave-particle description might be the most accurate interpretation, which leads us to develop a mathe- matical abstraction. 1 Rules for 1-D Quantum Mechanics Our mathematical abstraction of choice is the wave function, sometimes denoted as , and it allows us to predict the statistical outcomes of experiments (i.e., the outcomes of our measurements) according to a few rules 1. At any given time, the state of a physical system is represented by a wave function (x), which|for our purposes|is a complex, scalar function dependent on position. The quantity ρ (x) = ∗ (x) (x) is a probability density function. Furthermore, is complete, and tells us everything there is to know about the particle. 2. Every measurable attribute of a physical system is represented by an operator that acts on the wave function. In 6.007, we're largely interested in position (x^) and momentum (p^) which have operator representations in the x-dimension @ x^ ! x p^ ! ~ : (1) i @x Outcomes of measurements are described by the expectation values of the operator Z Z @ hx^i = dx ∗x hp^i = dx ∗ ~ : (2) i @x In general, any dynamical variable Q can be expressed as a function of x and p, and we can find the expectation value of Z h @ hQ (x; p)i = dx ∗Q x; : (3) i @x 3. -

Quantum Trajectory Distribution for Weak Measurement of A

Quantum Trajectory Distribution for Weak Measurement of a Superconducting Qubit: Experiment meets Theory Parveen Kumar,1, ∗ Suman Kundu,2, † Madhavi Chand,2, ‡ R. Vijayaraghavan,2, § and Apoorva Patel1, ¶ 1Centre for High Energy Physics, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, India 2Department of Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science, Tata Institue of Fundamental Research, Mumbai 400005, India (Dated: April 11, 2018) Quantum measurements are described as instantaneous projections in textbooks. They can be stretched out in time using weak measurements, whereby one can observe the evolution of a quantum state as it heads towards one of the eigenstates of the measured operator. This evolution can be understood as a continuous nonlinear stochastic process, generating an ensemble of quantum trajectories, consisting of noisy fluctuations on top of geodesics that attract the quantum state towards the measured operator eigenstates. The rate of evolution is specific to each system-apparatus pair, and the Born rule constraint requires the magnitudes of the noise and the attraction to be precisely related. We experimentally observe the entire quantum trajectory distribution for weak measurements of a superconducting qubit in circuit QED architecture, quantify it, and demonstrate that it agrees very well with the predictions of a single-parameter white-noise stochastic process. This characterisation of quantum trajectories is a powerful clue to unraveling the dynamics of quantum measurement, beyond the conventional axiomatic quantum -

Quantum Theory: Exact Or Approximate?

Quantum Theory: Exact or Approximate? Stephen L. Adler§ Institute for Advanced Study, Einstein Drive, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA Angelo Bassi† Department of Theoretical Physics, University of Trieste, Strada Costiera 11, 34014 Trieste, Italy and Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Trieste Section, Via Valerio 2, 34127 Trieste, Italy Quantum mechanics has enjoyed a multitude of successes since its formulation in the early twentieth century. It has explained the structure and interactions of atoms, nuclei, and subnuclear particles, and has given rise to revolutionary new technologies. At the same time, it has generated puzzles that persist to this day. These puzzles are largely connected with the role that measurements play in quantum mechanics [1]. According to the standard quantum postulates, given the Hamiltonian, the wave function of quantum system evolves by Schr¨odinger’s equation in a predictable, de- terministic way. However, when a physical quantity, say z-axis spin, is “measured”, the outcome is not predictable in advance. If the wave function contains a superposition of components, such as spin up and spin down, which each have a definite spin value, weighted by coe±cients cup and cdown, then a probabilistic distribution of outcomes is found in re- peated experimental runs. Each repetition gives a definite outcome, either spin up or spin down, with the outcome probabilities given by the absolute value squared of the correspond- ing coe±cient in the initial wave function. This recipe is the famous Born rule. The puzzles posed by quantum theory are how to reconcile this probabilistic distribution of outcomes with the deterministic form of Schr¨odinger’s equation, and to understand precisely what constitutes a “measurement”. -

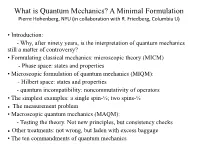

What Is Quantum Mechanics? a Minimal Formulation Pierre Hohenberg, NYU (In Collaboration with R

What is Quantum Mechanics? A Minimal Formulation Pierre Hohenberg, NYU (in collaboration with R. Friedberg, Columbia U) • Introduction: - Why, after ninety years, is the interpretation of quantum mechanics still a matter of controversy? • Formulating classical mechanics: microscopic theory (MICM) - Phase space: states and properties • Microscopic formulation of quantum mechanics (MIQM): - Hilbert space: states and properties - quantum incompatibility: noncommutativity of operators • The simplest examples: a single spin-½; two spins-½ ● The measurement problem • Macroscopic quantum mechanics (MAQM): - Testing the theory. Not new principles, but consistency checks ● Other treatments: not wrong, but laden with excess baggage • The ten commandments of quantum mechanics Foundations of Quantum Mechanics • I. What is quantum mechanics (QM)? How should one formulate the theory? • II. Testing the theory. Is QM the whole truth with respect to experimental consequences? • III. How should one interpret QM? - Justify the assumptions of the formulation in I - Consider possible assumptions and formulations of QM other than I - Implications of QM for philosophy, cognitive science, information theory,… • IV. What are the physical implications of the formulation in I? • In this talk I shall only be interested in I, which deals with foundations • II and IV are what physicists do. They are not foundations • III is interesting but not central to physics • Why is there no field of Foundations of Classical Mechanics? - We wish to model the formulation of QM on that of CM Formulating nonrelativistic classical mechanics (CM) • Consider a system S of N particles, each of which has three coordinates (xi ,yi ,zi) and three momenta (pxi ,pyi ,pzi) . • Classical mechanics represents this closed system by objects in a Euclidean phase space of 6N dimensions. -

Fourier Transformations & Understanding Uncertainty

Fourier Transformations & Understanding Uncertainty Uncertainty Relation: Fourier Analysis of Wave Packets Group 1: Brian Allgeier, Chris Browder, Brian Kim (7 December 2015) Introduction: In Quantum Mechanics, wave functions offer statistical information about possible results, not the exact outcome of an experiment. Two wave functions of interest are the position wave function and the momentum wave function; these wave functions represent the components of a state vector in the position basis and the momentum basis, respectively. These two can be related through the Fourier Transform and the Inverse Fourier Transform. This demonstration application will allow the users to define their own momentum wave function and use the inverse Fourier transformation to find the position wave function. If the Fourier transform were to be used on the resulting wave function, the result would then be the original momentum wave function. Both wave functions visually show the wave packets in momentum and position space. The momentum wave packet is a Gaussian while the corresponding position wave packet is a Gaussian envelope which contains an internal oscillatory wave. The two wave packets are related by the uncertainty principle, which states that the more defined (i.e. more localized) the wave function is in one basis, the less defined the corresponding wave function will be in the other basis. The application will also create an interactive 3-dimensional model that relates the two wave functions through the inverse Fourier transformation, or more specifically, by visually decomposing a Gaussian wave packet (in momentum space) into a specified number of components waves (in position space). Using this application will give the user a stronger knowledge of the relationship between the Fourier transform, inverse Fourier transform, and the relationship between wave packets in momentum space and position space as determined by the Uncertainty Principle. -

Informal Introduction to QM: Free Particle

Chapter 2 Informal Introduction to QM: Free Particle Remember that in case of light, the probability of nding a photon at a location is given by the square of the square of electric eld at that point. And if there are no sources present in the region, the components of the electric eld are governed by the wave equation (1D case only) ∂2u 1 ∂2u − =0 (2.1) ∂x2 c2 ∂t2 Note the features of the solutions of this dierential equation: 1. The simplest solutions are harmonic, that is u ∼ exp [i (kx − ωt)] where ω = c |k|. This function represents the probability amplitude of photons with energy ω and momentum k. 2. Superposition principle holds, that is if u1 = exp [i (k1x − ω1t)] and u2 = exp [i (k2x − ω2t)] are two solutions of equation 2.1 then c1u1 + c2u2 is also a solution of the equation 2.1. 3. A general solution of the equation 2.1 is given by ˆ ∞ u = A(k) exp [i (kx − ωt)] dk. −∞ Now, by analogy, the rules for matter particles may be found. The functions representing matter waves will be called wave functions. £ First, the wave function ψ(x, t)=A exp [i(px − Et)/] 8 represents a particle with momentum p and energy E = p2/2m. Then, the probability density function P (x, t) for nding the particle at x at time t is given by P (x, t)=|ψ(x, t)|2 = |A|2 . Note that the probability distribution function is independent of both x and t. £ Assume that superposition of the waves hold.