Understanding Visual Metaphors: What Graphic Novels Can Teach Lawyers About Visual Storytelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Treacherous 'Saracens' and Integrated Muslims

TREACHEROUS ‘SARACENS’ AND INTEGRATED MUSLIMS: THE ISLAMIC OUTLAW IN ROBIN HOOD’S BAND AND THE RE-IMAGINING OF ENGLISH IDENTITY, 1800 TO THE PRESENT 1 ERIC MARTONE Stony Brook University [email protected] 53 In a recent Associated Press article on the impending decay of Sherwood Forest, a director of the conservancy forestry commission remarked, “If you ask someone to think of something typically English or British, they think of the Sherwood Forest and Robin Hood… They are part of our national identity” (Schuman 2007: 1). As this quote suggests, Robin Hood has become an integral component of what it means to be English. Yet the solidification of Robin Hood as a national symbol only dates from the 19 th century. The Robin Hood legend is an evolving narrative. Each generation has been free to appropriate Robin Hood for its own purposes and to graft elements of its contemporary society onto Robin’s medieval world. In this process, modern society has re-imagined the past to suit various needs. One of the needs for which Robin Hood has been re-imagined during late modern history has been the refashioning of English identity. What it means to be English has not been static, but rather in a constant state of revision during the past two centuries. Therefore, Robin Hood has been adjusted accordingly. Fictional narratives erase the incongruities through which national identity was formed into a linear and seemingly inevitable progression, thereby fashioning modern national consciousness. As social scientist Etiénne Balibar argues, the “formation of the nation thus appears as the fulfillment of a ‘project’ stretching over centuries, in which there are different stages and moments of coming to self-awareness” (1991: 86). -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Marvel Fairy Tales by C.B. Cebulski Comic Book / Marvel Fairy Tales

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Marvel Fairy Tales by C.B. Cebulski Comic Book / Marvel Fairy Tales. Marvel Fairy Tales is a set of limited series published by Marvel Comics from 2006 to 2008 that adapts classic fairy tales, or invokes their tropes and traditions, and places Marvel's own famous characters in the roles. So far, there have been three series: Spider-Man Fairy Tales , X-Men Fairy Tales , and The Avengers Fairy Tales . A series based on Fantastic Four was planned but never realized. The stories are all written by C.B. Cebulski, and have a different artist for every story. Here is a list of fairy tales adapted: Spider-Man Fairy Tales: Little Red Riding Hood with Mary Jane Watson as Red, Peter as the woodsman, Aunt May in the role of the grandmother, and a wolf that looks suspiciously like Venom. A tribute to the African folk stories of Anansi with Spidey as Anansi (naturally), and featuring elementals that are modeled after Hydro-Man, Sandman, Cyclone, Swarm, and the Green Goblin. X-Men Fairy Tales: Momotarō with Cyclops as Momotaro, Professor X as the monk, Iceman as the dog, Beast as the monkey, Angel as the pheasant, Jean Grey as the monk's daughter, and Magneto, Quicksilver, Scarlet Witch, and Toad as the oni who captured Jean. Mystique, Pyro, and Avalanche also cameo as thieves who attack the monk. The Tortoise and the Eagle with Professor X as the Tortoise and Magneto as the Eagle. A story in the style of Grimm with Cyclops as a blind man who awakens a Phoenix princess, and Wolverine as a butcher who has encountered her before. -

CAPTAIN AMERICA–THE WINTER SOLDIER CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

CAPTAIN AMERICA–THE WINTER SOLDIER CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2014 WizKids/NECA LLC. © MARVEL PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Under Pages to Print>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 3. Under Page Sizing & Handling>Size select Actual size. 4. Under Page Sizing & Handling>Multiple>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 1 by 2. 5. Under Page Sizing & Handling>Multiple> Orientation select Landscape. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border (under Page Sizing & Handling>Multiple). 7. Click OK. ©2014 WizKids/NECA LLC. © MARVEL TABLE OF CONTENTS Agent 13™, 16 Agent Sitwell™, 17 Batroc™, 7 Black Widow™, 6 Brock Rumlow™, 13 Captain America™ (Present), 4 Captain America™ (WWII), 15 Captain America™ and Black Widow™, 20 Captain America™ and Bucky™, 21 Falcon™, 9 Maria Hill™, 14 Nick Fury™, 18 S.H.I.E.L.D. Agent™, 8 S.H.I.E.L.D. Commander™, 10 S.H.I.E.L.D. Soldier™, 5 Steve Rogers™, 12 Winter Soldier™, 11 Winter Soldier™ (Shield), 19 ©2014 WizKids/NECA LLC. © MARVEL Captain America™ (Present) 001 CAPTAIN AMERICA™ NOT BAD WITH OTHER THINGS, EITHER Avengers, S.H.I.E.L.D., Soldier, Strike Team (Super Strength) THE COSTUME IS A LITTLE OLD-FASHIONED… (Toughness) You Aren’t the Mission …BUT IT GETS THE JOB DONE (Invulnerability) Espionage: Fight On Our Terms If Captain America is part of a themed team, opponents do not modify the result of the roll to establish the first player. -

May 2017 New Releases

MAY 2017 NEW RELEASES GRAPHIC NOVELS • MANGA • SCI-FI/ FANTASY • GAMES VORACIOUS : FEEDING TIME Hunting dinosaurs and secretly serving them at his restaurant, Fork & Fossil, has helped Chef ISBN-13: 978-1-63229-235-3 Nate Willner become a big success. But just when he’s starting to make something of his life, Price: $17.99 ($23.99 CAN) Publisher: Action Lab he discovers that his hunting trips with Captain Jim are actually taking place in an alternate Entertainment reality – an Earth where dinosaurs evolve into Saurians, a technologically advanced race that Writer: Markisan Naso rules the far future! Some of these Saurians have mysteriously started vanishing from Artist: Jason Muhr Cretaceous City and the local authorities are hell-bent on finding who’s responsible. Nate’s Page Count: 160 world is about to collide with something much, much bigger than any dinosaur he’s ever Format: Softcover, Full Color Recommended Age: Mature roasted. Readers (ages 16 and up) Genre: Science Fiction Collecting VORACIOUS: Feeding Time #1-5, this second volume of the critically acclaimed Ship Date: 6/6/2017 series serves up a colorful bowl of characters and a platter full of sci-fi adventure, mystery and heart! SELECTED PREVIOUS VOLUMES: • Voracious: Diners, Dinosaurs & Dives (ISBN-13 978-1-63229-165-3, $14.99) PROVIDENCE ACT 1 FINAL PRINTING HC Due to overwhelming demand, we offer one final printing of the Providence Act 1 Hardcover! ISBN-13: 978-1-59291-291-9 Alan Moore’s quintessential horror series has set the standard for a terrifying reinvention of Price: $19.99 ($26.50 CAN) Publisher: Avatar Press the works of H.P. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Graphic Novel Titles

Comics & Libraries : A No-Fear Graphic Novel Reader's Advisory Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives February 2017 Beginning Readers Series Toon Books Phonics Comics My First Graphic Novel School Age Titles • Babymouse – Jennifer & Matthew Holm • Squish – Jennifer & Matthew Holm School Age Titles – TV • Disney Fairies • Adventure Time • My Little Pony • Power Rangers • Winx Club • Pokemon • Avatar, the Last Airbender • Ben 10 School Age Titles Smile Giants Beware Bone : Out from Boneville Big Nate Out Loud Amulet The Babysitters Club Bird Boy Aw Yeah Comics Phoebe and Her Unicorn A Wrinkle in Time School Age – Non-Fiction Jay-Z, Hip Hop Icon Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain The Donner Party The Secret Lives of Plants Bud : the 1st Dog to Cross the United States Zombies and Forces and Motion School Age – Science Titles Graphic Library series Science Comics Popular Adaptations The Lightning Thief – Rick Riordan The Red Pyramid – Rick Riordan The Recruit – Robert Muchamore The Nature of Wonder – Frank Beddor The Graveyard Book – Neil Gaiman Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children – Ransom Riggs House of Night – P.C. Cast Vampire Academy – Richelle Mead Legend – Marie Lu Uglies – Scott Westerfeld Graphic Biographies Maus / Art Spiegelman Anne Frank : the Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography Johnny Cash : I See a Darkness Peanut – Ayun Halliday and Paul Hope Persepolis / Marjane Satrapi Tomboy / Liz Prince My Friend Dahmer / Derf Backderf Yummy : The Last Days of a Southside Shorty -

American Sniper"

"AMERICAN SNIPER" by Chris Kyle with Scott McEwen and Jim DeFelice Screenplay By Jason Hall Second Draft 07.17.13 All gave some. Some gave all. OVER BLACK The groan of tank treads drowns out THE CALL TO PRAYER as an entire MARINE COMPANY advances over the top of us. EXT. STREET, FALLUJAH, IRAQ - DAY The sun melts over squat residences on a narrow street. The MARINE COMPANY creeps toward us like a cautious Goliath. FOOT SOLDIERS walk alongside Humvees and tanks. COMMANDING OFFICER (OS) (radio chatter) Charlie Bravo-3, we got eyes on you from the east. Clear to proceed, over. EXT. ROOFTOP, “OVERWATCH” - SAME Sun glints off a slab of corrugated steel. Beneath it-- CHRIS KYLE lays prone, dick in the dirt, eye to the glass of a .300 Win-Mag sniper rifle. He’s Texas stock with a boyish grin, blondish goatee and vital blue eyes. Both those eyes are open as he tracks the scene below, sweating his ass off in the shade of steel. CHRIS KYLE Fucking hot box. GOAT (24, Arkansas Marine) lies beside him, woodsy and outspoken, watching dirt-devils swirl in the street. GOAT Dirt over here tastes like dog shit. CHRIS KYLE I guess you’d know. Goat balks and fixes his M4 on the door. CHRIS SCOPE POV TRACK ACROSS bombed-out buildings, twisted metal and golden-domed mosques. Ragged curtains flutter out a window. Cat-tails on the river sway the same direction. We are seeing what he’s thinking as-- SFX: A LOW FREQUENCY BUZZ escalates over picture as his concentration deepens. -

THE PUNISHER WAR JOURNAL by Luis Filipe Based on Marvel Comics

THE PUNISHER THE PUNISHER WARWAR JOURNALJOURNAL by Luis Filipe Based on Marvel Comics character Copyright (c) 2017 This is just a fan made [email protected] OVER BLACK The sound of a POLICE RADIO calling. RADIO All units. Central Park shooting, requiring reinforcements immediately. CUT TO: CELL PHONE POV: Filming towards of Central Park alongside more people. Everyone horrified, but we don't know for what yet. CUT TO: VIDEO FOOTAGE: Now in Central Park where the police and CSI surround an entire area that is filled with CORPSES. A REPORTER talks to the camera. REPORTER Today New York witnessed the biggest outdoor massacre. It is speculated that the victims are members of the Mafia or even gangs, but no confirmation from the police yet. CUT TO: ANOTHER FOOTAGE: With the cameraman zooming in the forensic putting some bodies in black bags. One of them we notice that it's a little girl, and another a woman. REPORTER (O.S.) Apparently there was only one survivor. The victim is in serious condition but the paramedics doubt that he will hold it for long. CUT TO: SHAKY FOOTAGE: The only surviving man being taken on the stretcher to an ambulance. An oxygen mask on his face. His body covered in blood. He still uses his last forces to murmur. MAN My family... I want my... family. He is placed inside the ambulance. As the paramedics slam the ambulance doors - CUT TO BLACK: 2. Then - FADE IN: INT. CASTLE'S APARTMENT - DAY A small place with little furniture. The curtain blocks the sun from the single window of the apartment, allowing only a wispy sunlight to enter. -

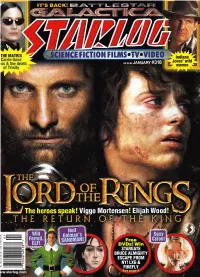

Starlog Magazine

THE MATRIX SCIENCE FICTION FILMS*TV*VIDEO Indiana Carrie-Anne 4 Jones' wild iss & the death JANUARY #318 r women * of Trinity Exploit terrain to gain tactical advantages. 'Welcome to Middle-earth* The journey begins this fall. OFFICIAL GAME BASED OS ''HE I.l'l't'.RAKY WORKS Of J.R.R. 'I'OI.KIKN www.lordoftherings.com * f> Sunita ft* NUMBER 318 • JANUARY 2004 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE ^^^^ INSIDEiRicinE THISti 111* ISSUEicri ir 23 NEIL CAIMAN'S DREAMS The fantasist weaves new tales of endless nights 28 RICHARD DONNER SPEAKS i v iu tuuay jfck--- 32 FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY Creator is \ 1 *-^J^ Joss Whedon glad to see his saga out on DVD 36 INDY'S WOMEN L/UUUy ICLdll IMC dLLIUII 40 GALACTICA 2.0 Ron Moore defends his plans for the brand-new Battlestar 46 THE WARRIOR KING Heroic Viggo Mortensen fights to save Middle-Earth 50 FRODO LIVES Atop Mount Doom, Elijah Wood faces a final test 54 OF GOOD FELLOWSHIP Merry turns grim as Dominic Monaghan joins the Riders 58 THAT SEXY CYLON! Tricia Heifer is the model of mocmodern mini-series menace 62 LANDniun OFAC THETUE BEARDEAD Disney's new animated film is a Native-American fantasy 66 BEING & ELFISHNESS Launch into space As a young man, Will Ferrell warfare with the was raised by Elves—no, SCI Fl Channel's new really Battlestar Galactica (see page 40 & 58). 71 KEYMAKER UNLOCKED! Does Randall Duk Kim hold the key to the Matrix mysteries? 74 78 PAINTING CYBERWORLDS Production designer Paterson STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., Owen 475 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

The Lawyer As Superhero: How Marvel Comics' Daredevil Depicts

Barry University School of Law Digital Commons @ Barry Law Faculty Scholarship Spring 5-2019 The Lawyer as Superhero: How Marvel Comics' Daredevil Depicts the American Court System and Legal Practice Louis Michael Rosen Barry University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/facultyscholarship Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation 47 Capital U. L. Rev. 379 (2019) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Barry Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Barry Law. THE LAWYER AS SUPERHERO: HOW MARVEL COMICS’ DAREDEVIL DEPICTS THE AMERICAN COURT SYSTEM AND LEGAL PRACTICE LOUIS MICHAEL ROSEN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 380 II. BACKGROUND: POPULAR CULTURE AND THE LAW THEORIES ....... 387 III. DAREDEVIL––THE STORY SO FAR ............................................... 391 A. Daredevil in the Sights of Frank Miller ....................................... 391 B. Daredevil Through the Eyes of Brian Michael Bendis ................ 395 C. Daredevil’s Journey to Redemption by David Hine .................... 402 D. Daredevil Goes Public, by Mark Waid ........................................ 406 IV. DAREDEVIL’S FRESH START AND BIGGEST CASE EVER, BY CHARLES SOULE ...................................................................................... 417 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................................... 430 Copyright © 2019, Louis Michael Rosen. * Louis Michael Rosen is a Reference Librarian and Associate Professor of Law Library at Barry University School of Law in Orlando, Florida. He would like to thank Professor Taylor Simpson-Wood, his mentor, ally, advocate, cheerleader, and ever-patient editor as he wrote this article. -

What Superman Teaches Us About the American Dream and Changing Values Within the United States

TRUTH, JUSTICE, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: WHAT SUPERMAN TEACHES US ABOUT THE AMERICAN DREAM AND CHANGING VALUES WITHIN THE UNITED STATES Lauren N. Karp AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lauren N. Karp for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 4, 2009 . Title: Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States Abstract approved: ____________________________________________________________________ Evan Gottlieb This thesis is a study of the changes in the cultural definition of the American Dream. I have chosen to use Superman comics, from 1938 to the present day, as litmus tests for how we have societally interpreted our ideas of “success” and the “American Way.” This work is primarily a study in culture and social changes, using close reading of comic books to supply evidence. I argue that we can find three distinct periods where the definition of the American Dream has changed significantly—and the identity of Superman with it. I also hypothesize that we are entering an era with an entirely new definition of the American Dream, and thus Superman must similarly change to meet this new definition. Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States by Lauren N. Karp A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 4, 2009 Commencement June 2010 Master of Arts thesis of Lauren N. Karp presented on June 4, 2009 APPROVED: ____________________________________________________________________ Major Professor, representing English ____________________________________________________________________ Chair of the Department of English ____________________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries.