A Anhang: Perfekte Sicherheit Und Praktische Sicherheit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Encryption Techniques

CPE 542: CRYPTOGRAPHY & NETWORK SECURITY Chapter 2: Classical Encryption Techniques Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Computer Engineering Department Jordan University of Science and Technology Jordan Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Fall 2005 Introduction Basic Terminology • plaintext - the original message • ciphertext - the coded message • key - information used in encryption/decryption, and known only to sender/receiver • encipher (encrypt) - converting plaintext to ciphertext using key • decipher (decrypt) - recovering ciphertext from plaintext using key • cryptography - study of encryption principles/methods/designs • cryptanalysis (code breaking) - the study of principles/ methods of deciphering ciphertext Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Fall 2005 1 Cryptographic Systems Cryptographic Systems are categorized according to: 1. The operation used in transferring plaintext to ciphertext: • Substitution: each element in the plaintext is mapped into another element • Transposition: the elements in the plaintext are re-arranged. 2. The number of keys used: • Symmetric (private- key) : both the sender and receiver use the same key • Asymmetric (public-key) : sender and receiver use different key 3. The way the plaintext is processed : • Block cipher : inputs are processed one block at a time, producing a corresponding output block. • Stream cipher: inputs are processed continuously, producing one element at a time (bit, Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Fall 2005 Cryptographic Systems Symmetric Encryption Model Dr. Lo’ai Tawalbeh Fall 2005 2 Cryptographic Systems Requirements • two requirements for secure use of symmetric encryption: 1. a strong encryption algorithm 2. a secret key known only to sender / receiver •Y = Ek(X), where X: the plaintext, Y: the ciphertext •X = Dk(Y) • assume encryption algorithm is known •implies a secure channel to distribute key Dr. -

Download Download

International Journal of Integrated Engineering: Special Issue 2018: Data Information Engineering, Vol. 10 No. 6 (2018) p. 183-192. © Penerbit UTHM DOI: https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2018.10.06.026 Analysis of Four Historical Ciphers Against Known Plaintext Frequency Statistical Attack Chuah Chai Wen1*, Vivegan A/L Samylingam2, Irfan Darmawan3, P.Siva Shamala A/P Palaniappan4, Cik Feresa Mohd. Foozy5, Sofia Najwa Ramli6, Janaka Alawatugoda7 1,2,4,5,6Information Security Interest Group (ISIG), Faculty Computer Science and Information Technology University Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Batu Pahat, Johor, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], {shamala, feresa, sofianajwa}@uthm.edu.my 3School of Industrial Engineering, Telkom University, 40257 Bandung, West Java, Indonesia 7Department of Computer Engineering, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] Received 28 June 2018; accepted 5August 2018, available online 24 August 2018 Abstract: The need of keeping information securely began thousands of years. The practice to keep the information securely is by scrambling the message into unreadable form namely ciphertext. This process is called encryption. Decryption is the reverse process of encryption. For the past, historical ciphers are used to perform encryption and decryption process. For example, the common historical ciphers are Hill cipher, Playfair cipher, Random Substitution cipher and Vigenère cipher. This research is carried out to examine and to analyse the security level of these four historical ciphers by using known plaintext frequency statistical attack. The result had shown that Playfair cipher and Hill cipher have better security compare with Vigenère cipher and Random Substitution cipher. -

COS433/Math 473: Cryptography Mark Zhandry Princeton University Spring 2017 Cryptography Is Everywhere a Long & Rich History

COS433/Math 473: Cryptography Mark Zhandry Princeton University Spring 2017 Cryptography Is Everywhere A Long & Rich History Examples: • ~50 B.C. – Caesar Cipher • 1587 – Babington Plot • WWI – Zimmermann Telegram • WWII – Enigma • 1976/77 – Public Key Cryptography • 1990’s – Widespread adoption on the Internet Increasingly Important COS 433 Practice Theory Inherent to the study of crypto • Working knowledge of fundamentals is crucial • Cannot discern security by experimentation • Proofs, reductions, probability are necessary COS 433 What you should expect to learn: • Foundations and principles of modern cryptography • Core building blocks • Applications Bonus: • Debunking some Hollywood crypto • Better understanding of crypto news COS 433 What you will not learn: • Hacking • Crypto implementations • How to design secure systems • Viruses, worms, buffer overflows, etc Administrivia Course Information Instructor: Mark Zhandry (mzhandry@p) TA: Fermi Ma (fermima1@g) Lectures: MW 1:30-2:50pm Webpage: cs.princeton.edu/~mzhandry/2017-Spring-COS433/ Office Hours: please fill out Doodle poll Piazza piaZZa.com/princeton/spring2017/cos433mat473_s2017 Main channel of communication • Course announcements • Discuss homework problems with other students • Find study groups • Ask content questions to instructors, other students Prerequisites • Ability to read and write mathematical proofs • Familiarity with algorithms, analyZing running time, proving correctness, O notation • Basic probability (random variables, expectation) Helpful: • Familiarity with NP-Completeness, reductions • Basic number theory (modular arithmetic, etc) Reading No required text Computer Science/Mathematics Chapman & Hall/CRC If you want a text to follow along with: Second CRYPTOGRAPHY AND NETWORK SECURITY Cryptography is ubiquitous and plays a key role in ensuring data secrecy and Edition integrity as well as in securing computer systems more broadly. -

Amy Bell Abilene, TX December 2005

Compositional Cryptology Thesis Presented to the Honors Committee of McMurry University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Undergraduate Honors in Math By Amy Bell Abilene, TX December 2005 i ii Acknowledgements I could not have completed this thesis without all the support of my professors, family, and friends. Dr. McCoun especially deserves many thanks for helping me to develop the idea of compositional cryptology and for all the countless hours spent discussing new ideas and ways to expand my thesis. Because of his persistence and dedication, I was able to learn and go deeper into the subject matter than I ever expected. My committee members, Dr. Rittenhouse and Dr. Thornburg were also extremely helpful in giving me great advice for presenting my thesis. I also want to thank my family for always supporting me through everything. Without their love and encouragement I would never have been able to complete my thesis. Thanks also should go to my wonderful roommates who helped to keep me motivated during the final stressful months of my thesis. I especially want to thank my fiancé, Gian Falco, who has always believed in me and given me so much love and support throughout my college career. There are many more professors, coaches, and friends that I want to thank not only for encouraging me with my thesis, but also for helping me through all my pursuits at school. Thank you to all of my McMurry family! iii Preface The goal of this research was to gain a deeper understanding of some existing cryptosystems, to implement these cryptosystems in a computer programming language of my choice, and to discover whether the composition of cryptosystems leads to greater security. -

Historical Ciphers • A

ECE 646 - Lecture 6 Required Reading • W. Stallings, Cryptography and Network Security, Chapter 2, Classical Encryption Techniques Historical Ciphers • A. Menezes et al., Handbook of Applied Cryptography, Chapter 7.3 Classical ciphers and historical development Why (not) to study historical ciphers? Secret Writing AGAINST FOR Steganography Cryptography (hidden messages) (encrypted messages) Not similar to Basic components became modern ciphers a part of modern ciphers Under special circumstances modern ciphers can be Substitution Transposition Long abandoned Ciphers reduced to historical ciphers Transformations (change the order Influence on world events of letters) Codes Substitution The only ciphers you Ciphers can break! (replace words) (replace letters) Selected world events affected by cryptology Mary, Queen of Scots 1586 - trial of Mary Queen of Scots - substitution cipher • Scottish Queen, a cousin of Elisabeth I of England • Forced to flee Scotland by uprising against 1917 - Zimmermann telegram, America enters World War I her and her husband • Treated as a candidate to the throne of England by many British Catholics unhappy about 1939-1945 Battle of England, Battle of Atlantic, D-day - a reign of Elisabeth I, a Protestant ENIGMA machine cipher • Imprisoned by Elisabeth for 19 years • Involved in several plots to assassinate Elisabeth 1944 – world’s first computer, Colossus - • Put on trial for treason by a court of about German Lorenz machine cipher 40 noblemen, including Catholics, after being implicated in the Babington Plot by her own 1950s – operation Venona – breaking ciphers of soviet spies letters sent from prison to her co-conspirators stealing secrets of the U.S. atomic bomb in the encrypted form – one-time pad 1 Mary, Queen of Scots – cont. -

"Cyber Security" Activity

Cyber Security Keeping your information safe Standards: (Core ideas related to the activity) NGSS: ETS1.B – A solution needs to be tested and them modified on the basis of the test results in order to improve it MS-PS4.C – Digitized signals sent as wave pulses are a more reliable way to encode and transmit information CC Math: 5.OA-3 – Analyze patterns and relationships K12CS: 3-5 CS-Devices – Computing devices may be connected to other devices or components to extend their capabilities. Connections can take many forms such as physical or wireless. 3-5 N&I-Cybersecurity – Information can be protected using various security measures. These measures can be physical or digital 3-5 IoC-Culture – The development and modification of computing technology is driven by people’s needs and wants and can affect different groups differently 6-8 CS-Devices – The interaction between humans and computing devices presents advantages, disadvantages, and unintended consequences. The study of human-computer interaction can improve the design of devices and extend the abilities of humans. 6-8 N&I-Cybersecurity – The information sent and received across networks can be protected from unauthorized access and modification in a variety of ways, such as encryption to maintain its confidentiality and restricted access to maintain its integrity. Security measures to safeguard online information proactively address the threat of breaches to personal and private data 6-8 A&P-Algorithms – Algorithms affect how people interact with computers and the way computers respond. People design algorithms that are generalizable to many situations 6-8 IoC-Culture – Advancements in computing technology change people’s everyday activities. -

The Mathemathics of Secrets.Pdf

THE MATHEMATICS OF SECRETS THE MATHEMATICS OF SECRETS CRYPTOGRAPHY FROM CAESAR CIPHERS TO DIGITAL ENCRYPTION JOSHUA HOLDEN PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright c 2017 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR press.princeton.edu Jacket image courtesy of Shutterstock; design by Lorraine Betz Doneker All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Holden, Joshua, 1970– author. Title: The mathematics of secrets : cryptography from Caesar ciphers to digital encryption / Joshua Holden. Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016014840 | ISBN 9780691141756 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Cryptography—Mathematics. | Ciphers. | Computer security. Classification: LCC Z103 .H664 2017 | DDC 005.8/2—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016014840 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Linux Libertine Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 13579108642 To Lana and Richard for their love and support CONTENTS Preface xi Acknowledgments xiii Introduction to Ciphers and Substitution 1 1.1 Alice and Bob and Carl and Julius: Terminology and Caesar Cipher 1 1.2 The Key to the Matter: Generalizing the Caesar Cipher 4 1.3 Multiplicative Ciphers 6 -

CS 241 Data Organization Ciphers

CS 241 Data Organization Ciphers March 22, 2018 Cipher • In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption. • When using a cipher, the original information is known as plaintext, and the encrypted form as ciphertext. • The encrypting procedure of the cipher usually depends on a piece of auxiliary information, called a key. • A key must be selected before using a cipher to encrypt a message. • Without knowledge of the key, it should be difficult, if not nearly impossible, to decrypt the resulting ciphertext into readable plaintext. Substitution Cipher • In cryptography, a substitution cipher is a method of encryption by which units of plaintext are replaced with ciphertext according to a regular system. • Example: case insensitive substitution cipher using a shifted alphabet with keyword "zebras": • Plaintext alphabet: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ • Ciphertext alphabet: ZEBRASCDFGHIJKLMNOPQTUVWXY flee at once. we are discovered! Enciphers to SIAA ZQ LKBA. VA ZOA RFPBLUAOAR! Other substitution ciphers Caesar cipher Shift alphabet by fixed amount. (Caesar apparently used 3.) ROT13 Replace letters with those 13 away. Used to hide spoilers on newsgroups. pigpen cipher Replace letters with symbols. Substitution Cipher: Encipher Example OENp(ENTE#X@EN#zNp(ENCL]pEnN7p-pE;8N]LN} dnEdNp#Nz#duN-Nu#dENXEdzE9pNCL]#L8NE;p-b @];(N0G;p]9E8N]L;GdENn#uE;p]9Nld-L/G]@]p _8NXd#|]nENz#dNp(EN9#uu#LNnEzEL;E8NXd#u# pENp(ENQELEd-@NOE@z-dE8N-LnN;E9GdENp(EN^ @E;;]LQ;N#zN<]bEdp_Np#N#Gd;E@|E;N-LnN#Gd NT#;pEd]p_8Nn#N#dn-]LN-LnNE;p-b@];(Np(]; N5#L;p]pGp]#LNz#dNp(ENCL]pEnN7p-pE;N#zN) uEd]9-D Breaking a Substitution Cipher In English, • The most common character is the space: \ ". -

Index-Of-Coincidence.Pdf

The Index of Coincidence William F. Friedman in the 1930s developed the index of coincidence. For a given text X, where X is the sequence of letters x1x2…xn, the index of coincidence IC(X) is defined to be the probability that two randomly selected letters in the ciphertext represent, the same plaintext symbol. For a given ciphertext of length n, let n0, n1, …, n25 be the respective letter counts of A, B, C, . , Z in the ciphertext. Then, the index of coincidence can be computed as 25 ni (ni −1) IC = ∑ i=0 n(n −1) We can also calculate this index for any language source. For some source of letters, let p be the probability of occurrence of the letter a, p be the probability of occurrence of a € b the letter b, and so on. Then the index of coincidence for this source is 25 2 Isource = pa pa + pb pb +…+ pz pz = ∑ pi i=0 We can interpret the index of coincidence as the probability of randomly selecting two identical letters from the source. To see why the index of coincidence gives us useful information, first€ note that the empirical probability of randomly selecting two identical letters from a large English plaintext is approximately 0.065. This implies that an (English) ciphertext having an index of coincidence I of approximately 0.065 is probably associated with a mono-alphabetic substitution cipher, since this statistic will not change if the letters are simply relabeled (which is the effect of encrypting with a simple substitution). The longer and more random a Vigenere cipher keyword is, the more evenly the letters are distributed throughout the ciphertext. -

An Investigation Into Mathematical Cryptography with Applications

Project Report BSc (Hons) Mathematics An Investigation into Mathematical Cryptography with Applications Samuel Worton 1 CONTENTS Page: 1. Summary 3 2. Introduction to Cryptography 4 3. A History of Cryptography 6 4. Introduction to Modular Arithmetic 12 5. Caesar Cipher 16 6. Affine Cipher 17 7. Vigenère Cipher 19 8. Autokey Cipher 21 9. One-Time Pad 22 10. Pohlig-Hellman Encryption 24 11. RSA Encryption 27 12. MATLAB 30 13. Conclusion 35 14. Glossary 36 15. References 38 2 1. SUMMARY AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In this report, I will explore the history of cryptography, looking at the origins of cryptosystems in the BC years all the way through to the current RSA cryptosystem which governs the digital era we live in. I will explain the mathematics behind cryptography and cryptanalysis, which is largely based around number theory and in particular, modular arithmetic. I will relate this to several famous, important and relevant cryptosystems, and finally I will use the MATLAB program to write codes for a few of these cryptosystems. I would like to thank Mr. Kuldeep Singh for his feedback and advice during all stages of my report, as well as enthusiasm towards the subject. I would also like to thank Mr. Laurence Taylor for generously giving his time to help me in understanding and producing the MATLAB coding used towards the end of this investigation. Throughout this report I have been aided by the book ‘Elementary Number Theory’ by Mr. David M. Burton, amongst others, which was highly useful in refreshing my number theory knowledge and introducing me to the concepts of cryptography; also Mr. -

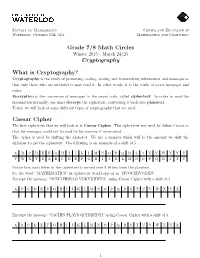

Grade 7/8 Math Circles Cryptography What Is Cryptography? Caesar Cipher

Faculty of Mathematics Centre for Education in Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Mathematics and Computing Grade 7/8 Math Circles Winter 2015 - March 24/25 Cryptography What is Cryptography? Cryptography is the study of protecting, coding, storing and transmitting information and messages so that only those who are intended to may read it. In other words, it is the study of secret messages and codes. Encryption is the conversion of messages to the secret code, called ciphertext. In order to read the information normally, one must decrypt the ciphertext, converting it back into plaintext. Today, we will look at some different types of cryptography that are used. Caesar Cipher The first ciphertext that we will look at is Caesar Cipher. This ciphertext was used by Julius Caesar so that his messages could not be read by his enemies if intercepted. The cipher is used by shifting the alphabet. We use a number which will be the amount we shift the alphabet to get the ciphertext. The following is an example of a shift of 5: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U Notice how each letter in the ciphertext is moved over 5 letters from the plaintext. So, the word \MATHEMATICS" in ciphertext would appear as \HVOCZHVODXN". Decrypt the message \NUWJ HKRAO YDKYKHWPA" using Caesar Cipher with a shift of 4. -

Automating the Development of Chosen Ciphertext Attacks

Automating the Development of Chosen Ciphertext Attacks Gabrielle Beck∗ Maximilian Zinkus∗ Matthew Green Johns Hopkins University Johns Hopkins University Johns Hopkins University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract In this work we consider a specific class of vulner- ability: the continued use of unauthenticated symmet- In this work we investigate the problem of automating the ric encryption in many cryptographic systems. While development of adaptive chosen ciphertext attacks on sys- the research community has long noted the threat of tems that contain vulnerable format oracles. Unlike pre- adaptive-chosen ciphertext attacks on malleable en- vious attempts, which simply automate the execution of cryption schemes [17, 18, 56], these concerns gained known attacks, we consider a more challenging problem: practical salience with the discovery of padding ora- to programmatically derive a novel attack strategy, given cle attacks on a number of standard encryption pro- only a machine-readable description of the plaintext veri- tocols [6,7, 13, 22, 30, 40, 51, 52, 73]. Despite repeated fication function and the malleability characteristics of warnings to industry, variants of these attacks continue to the encryption scheme. We present a new set of algo- plague modern systems, including TLS 1.2’s CBC-mode rithms that use SAT and SMT solvers to reason deeply ciphersuite [5,7, 48] and hardware key management to- over the design of the system, producing an automated kens [10, 13]. A generalized variant, the format oracle attack strategy that can entirely decrypt protected mes- attack can be constructed when a decryption oracle leaks sages.