Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GYPSY CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS: • Momma Rose

GYPSY CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS: • Momma Rose (age from 35 - 50) The ultimate stage mother. Lives her life vicariously through her two daughters, whom she's put into show business. She is loud, brash, pushy and single- minded, but at times can be doting and charming. She is holding down demons of her own that she is afraid to face. Her voice is the ultimate powerful Broadway belt. Minimal dance but must move well. Comic timing a must. Strong Mezzo/Alto with good low notes and belt. • Baby June (age 9-10) is a Shirley Temple-like up-and-coming vaudeville star, and Madam Rose's youngest daughter. Her onstage demeanor is sugary-sweet, cute, precocious and adorable to the nth degree. Needs to be no taller than 3', 5". An adorable character - Mama Rose's shining star. Strong child singer, strong dancer. Mezzo. • Young Louise (about 12) She should look a couple years older than Baby June. She is Madam Rose's brow-beaten oldest daughter, and has always played second fiddle to her baby sister. She is shy, awkward, a little sad and subdued; she doesn't have the confidence of her sister. Strong acting skills needed. The character always dances slightly out of step but the actress playing this part must be able to dance. Mezzo singer. • Herbie (about 45) agent for Rose's children and Rose's boyfriend and a possible husband number 4. He has a heart of gold but also has the power to defend the people he loves with strength. Minimum dance. A Baritone, sings in one group number, two duets and trio with Rose and Louise. -

Rose La Rose and the Re-Ownership of American Burlesque, 1935-1972

TAUGHT IT TO THE TRADE: ROSE LA ROSE AND THE RE-OWNERSHIP OF AMERICAN BURLESQUE, 1935-1972 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Wellman Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Jennifer Schlueter, Advisor Beth Kattelman Joy Reilly Copyright by Elizabeth Wellman 2015 ABSTRACT Declaring burlesque dead has been a habit of the twentieth century. Robert C. Allen quoted an 1890s letter from the first burlesque star of the American stage, Lydia Thompson in Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (1991): “[B]urlesque as she knew it ‘has been retired for a time,’ its glories now ‘merely memories of the stage.’”1 In 1931, Bernard Sobel opined in Burleycue: An Underground History of Burlesque Days, “Alas! You will never get a chance to see one of the real burlesque shows again. They are gone forever…”2 In 1938, The Billboard published an editorial that began, “On every hand the cry is ‘Burlesque is dead.’”3 In fact, burlesque had been declared dead so often that editorials began popping up insisting it could be revived, as Joe Schoenfeld’s 1943 op-ed in Variety did: “[It] may be in a state of putrefaction, but it is a lusty and kicking decomposition.”4 It is this “lusty and kicking decomposition” which characterizes the published history of burlesque. Since its modern inception in the late nineteenth century, American burlesque has both been framed and framed itself within this narrative of degeneration. -

Behind the Burly Q

BEHIND THE BURLY Q A film by Leslie Zemeckis HDCAM SR, 98 minutes, 2010 First Run Features 630 Ninth Avenue, Suite 1213 New York, NY 10036 [email protected] (212) 243-0600 PRAISE FOR BEHIND THE BURLY Q “Utterly entertaining Behind the Burly Q is a painstakingly researched love letter to the women and men who once made up the community of burlesque performers…its treasure trove of vintage photographs and performance footage is enough to make historians and fans of classic erotica swoon…insightful, fascinating.” –Ernest Hardy, The Village Voice CRITICS’ PICK! “Intriguing…fans of theatrical history are well advised to check it out” -New York Magazine “Charming, entertaining…a delight!” –Manohla Dargis, Behind the Burly Q “Provides a privileged front-row seat to sample several of the form's most memorable practitioners… stories run from raunchy to touching to funny to flat-out incredible.” –Ronnie Scheib, Variety “Affectionate and engaging…wonderful vintage footage, a fascinating glimpse into a corner of American history.” –New York Daily News “Fascinatingly strips away at the myths surrounding the most popular American entertainment form of the first half of the 20th century.” –Michael Musto, The Sundance Channel “Quickly paced, absorbing.” –Kyle Smith, The New York Post “History done right: informative, entertaining, funny and finally rather moving…jam-packed with juicy detail, and most of that jam is tasty indeed.”-James van Maanen, Trustmovies “Delightful, engaging…A veritable who's who of the grande dames of the burlesque stage…for -

P R E S S R E L E A

P R E S S R E L E A S E From: Clear Space Theatre Company Contact: Wesley Paulson Phone: 302.227.2270 Email: [email protected] February 17, 2017: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE “Let Me Entertain You,” invites Louise, as GYPSY comes to Clear Space Theatre for a three-week run. And entertain you this show surely will, weekends from March 10 through March 26. With music by Jule Styne, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and book by Arthur Laurents, Gypsy contains some of the most well- known – and best-loved – show music of all time, including, “Everything’s Coming Up Roses,” “Small World,” and “You Gotta Get a Gimmick.” Based loosely on the memoirs of striptease artist Gypsy Rose Lee, GYPSY traces Lee’s improbable rise to burlesque fame from her shy beginnings as Louise (Katharine Ariyan), the reluctant half of a vaudeville sister act featuring her younger, talented, extroverted sister, June (Grace Morris). It also reveals the formidable force behind that rise: Rose (Yvonne Erickson), the girls’ driven, relentless, mother-of-all- stage-mothers, who propels their careers through the waning days of vaudeville and delivers Louise onto the burlesque stage. Says Erickson, “Appearing as Rose is a long-time dream fulfilled! I saw Angela Lansbury in the 1974 Broadway revival of GYPSY and was just mesmerized. I had just begun to think about acting as a career, and after seeing that performance – I knew, ‘Yes! That’s what I want to do!’ The role of Rose is often referred to as the “King Lear role of musical theater” - it requires both gravitas and humanity. -

The Eclectic Collection of the Legendary Gypsy Rose Lee Featured in Julien’S Auctions’ Icons & Idols: Hollywood

For Immediate Release: THE ECLECTIC COLLECTION OF THE LEGENDARY GYPSY ROSE LEE FEATURED IN JULIEN’S AUCTIONS’ ICONS & IDOLS: HOLLYWOOD The World’s Most Famous Burlesque Artist Celebrated at Auction Event SPECIAL MEDIA PREVIEW OF COLLECTION IS MONDAY, DECEMBER 1, 2014 AUCTION IS DECEMBER 5, 2014 Beverly Hills, California – (November 24, 2014) – Famed burlesque artist and actress Gypsy Rose Lee will be celebrated at the Julien’s Auctions “Icons & Idols: Hollywood” event to take place on Friday, December 5, 2014. The eclectic collection of the remarkable entertainer is being presented by her son whose vast array of personal items and career effects is an emotional construct of his mother. Gypsy Rose Lee’s storied life included vaudeville at an early age and later when she became America’s most famed burlesque performer. She was a dancer, author, comedian, actress and even a playwright. Her mother Rose put her on the stage to perform her first strip tease at the age of 15. Gypsy later chose to embellish the act with comedy and acting and soon became a hit. Gypsy can often be credited as the originator of burlesque and the acts that followed thereafter. The fabled American Broadway musical “Gypsy” was based on Gypsy’s life and became a huge hit. As Gypsy herself once said, “If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing slowly,” and so she did on stage when she performed to thousands in her lifetime. The collection includes the gloves that were a trademark of the Gypsy Rose Lee strip, a set of towels that were monogrammed with her initials, the rhinestone studded heels from her act, the foxtail fur from the Tiger Rag shimmy dance that was the finale of her acts, her personal stone martin stole that she wore all the time and numerous other items including original art, jewelry, furnishings and other memorabilia which have kept her alive in the minds of fans, collectors and family for years. -

For Immediate Release

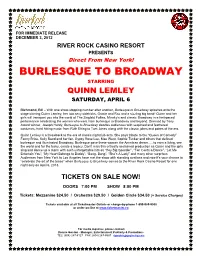

RB FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 3, 2012 RIVER ROCK CASINO RESORT PRESENTS Direct From New York! BURLESQUE TO BROADWAY STARRING QUINN LEMLEY SATURDAY, APRIL 6 Richmond, BC – With one show-stopping number after another, Burlesque to Broadway splashes onto the stage starring Quinn Lemley, her two sexy sidekicks, Gracie and Raz and a sizzling big band! Quinn and her girls will transport you into the world of The Ziegfeld Follies, Minsky’s and classic Broadway in a fast-paced performance celebrating the women who went from burlesque to Broadway and beyond. Directed by Tony Award winner, Joseph Hardy, Burlesque to Broadway dazzles audiences with sequined and feathered costumes, hard hitting music from Ruth Etting to Tom Jones along with the classic jokes and pokes of the era. Quinn Lemley is a throwback to the era of classic nightclub acts. She pays tribute to the “Queen of Comedy” Fanny Brice, Sally Rand and her fan, Gypsy Rose Lee, Mae West, Sophie Tucker and others that defined burlesque and illuminated Broadway. Burlesque gave these women the American dream … to earn a living, see the world and for the lucky, create a legacy. Don’t miss this critically acclaimed production as Quinn and the girls sing and dance up a storm with such unforgettable hits as “Hey Big Spender”, “Ten Cents a Dance”, “Let Me Entertain You”, “My Heart Belongs to Daddy”, “Bang, Bang”, “She’s A Lady” and many other surprises. Audiences from New York to Los Angeles have met the show with standing ovations and now it’s your chance to “celebrate the art of the tease” when Burlesque to Broadway comes to the River Rock Casino Resort for one night only on April 6, 2013. -

Two Infamous Homewreckers Meet in the New Stage Play, “The Duchess and the Stripper” the Duchess of Windsor, Wallis Simpson

Two Infamous Homewreckers Meet in the New Stage Play, “The Duchess and the Stripper” The Duchess of Windsor, Wallis Simpson, and the premier burlesque dancer of her time, Blaze Starr meet in the new stage play, “The Duchess and the Stripper,” making its world premiere in the Hollywood Fringe Festival in June 2019. The play takes place in 1961 Baltimore, at the Two O’Clock Club, the famous strip club owned by Blaze Starr. These two women who outwardly have nothing in common, in fact, shared a number of similar experiences. Their reactions to those events vary greatly due to their upbringing and yes, their social standing. The play has attracted great talent. The director, Ezra Buzzington, is not only a veteran of stage and screen, but co-founder of the New York Fringe Festival. “It has some of the wittiest dialogue I’ve read in years. I really wanted to be a part of it.” Playing the Duchess, Wallis Simpson is Miss Blaire Chandler, who’s last Fringe appearance as Big Mama in the multi-lauded Theatre of Note/TMB production of Hot Cat. Blaire is the winner of multiple drama critics’ awards across the country, and has appeared on stage in Los Angeles at The Road, Theatre of Note, Chalk Rep, and The Actors’ Gang. Regional Theatre: Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park; Santa Cruz Shakespeare. Off Broadway: The Public Theatre. Television: Paramount mini-series Waco, and CBS’ Criminal Minds. Twitter: @blairezdoodle. Blaze Starr will Be played By Miss Alli Miller. She s from Hooiser land and has a BA in musical theatre from Ball State University. -

Fang Family San Francisco Examiner Photograph Archive Negative Files, Circa 1930-2000, Circa 1930-2000

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb6t1nb85b No online items Finding Aid to the Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-2000, circa 1930-2000 Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2010 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Fang family San BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG 1 Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-... Finding Aid to the Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-2000, circa 1930-2000 Collection number: BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Bancroft Library staff Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files Date (inclusive): circa 1930-2000 Collection Number: BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG Creator: San Francisco Examiner (Firm) Extent: 3,200 boxes (ca. 3,600,000 photographic negatives); safety film, nitrate film, and glass : various film sizes, chiefly 4 x 5 in. and 35mm. Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: Local news photographs taken by staff of the Examiner, a major San Francisco daily newspaper. -

Doherty, Thomas, Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, Mccarthyism

doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page i COLD WAR, COOL MEDIUM TELEVISION, McCARTHYISM, AND AMERICAN CULTURE doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page ii Film and Culture A series of Columbia University Press Edited by John Belton What Made Pistachio Nuts? Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic Henry Jenkins Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle Martin Rubin Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II Thomas Doherty Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy William Paul Laughing Hysterically: American Screen Comedy of the 1950s Ed Sikov Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema Rey Chow The Cinema of Max Ophuls: Magisterial Vision and the Figure of Woman Susan M. White Black Women as Cultural Readers Jacqueline Bobo Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Film Darrell William Davis Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema Rhona J. Berenstein This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age Gaylyn Studlar Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond Robin Wood The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music Jeff Smith Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture Michael Anderegg Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, ‒ Thomas Doherty Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity James Lastra Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts Ben Singer -

A Musical Fable, Book by Arthur Laurents Music by Jule Styne Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Suggested by Memoirs of Gypsy Rose Lee O

Gypsy A Musical Fable, Book by Arthur Laurents Music by Jule Styne Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Suggested by memoirs of Gypsy Rose Lee Original production by David Merrick & Leland Hayward Entire production originally directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins Directed and choreographed by Kimberley Rampersad Music direction by Paul Sportelli Set designed by Cory Sincennes Costumes designed by Tamara Marie Kucheran Lighting designed by Kevin Fraser Sound designed by John Lott THE STORY Gypsy is a musical set in the backstage world of American vaudeville theatre during the early 20th century. There are two story lines: 1) The struggles of life in the theatre as performers chase their dreams of stardom, and 2) the universal story of a mother/daughter relationship. At the top of the show we meet Mama Rose. Rose is a domineering, brash stage-mother who dreams of fame and stardom for her daughters, Louise and June. Rose devotes her entire being to building their stage careers June, the younger daughter, is an extroverted, talented child star. The older daughter, Louise, is shy. Their kiddie Vaudeville act has one song, "Let Me Entertain You," that they sing over and over and over again, with June always as the center- piece and Louise in the background. The girls grow up and continue to perform the same act. June becomes tired of her mother’s influence and the endless touring. She elopes with one of the backup dancers. Rose is deeply hurt, but determinedly vows that she will now make Louise a star. Unfortunately, with the rise of radio and movies, the Vaudeville theatre jobs disappear. -

Political Challenges in the Neo-Burlesque Spectacle

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 2 (2020) Cyberlesqued Re/Viewings: Political Challenges in the Neo-burlesque Spectacle Mariza Tzouni ABSTRACT: Provided that the 1990s was characterized as an era of newness with the insertion of extreme technological advances, the rise of multiculturalism, new media expansion and the appearance of the World Wide Web, neo-burlesque appeared as an all-new form of entertainment which de/re/contextualized the act of viewing. Burlesque has been metamorphosed through the occurrence of neo-burlesque as an attempt to stress newness into the old; that is to re-generate a nationalized theatrical sub/genre to an inter/nationalized cyber/spectacle which re/acts against the sociopolitical distresses of the twenty-first century. Initiated with the Yahoo Group along with a plethora of online groups and blogs which have sprung till then, the Internet manages to weave a nexus among producers, performers and fans inter/nationally. It has also enabled neo-burlesque to cross over the national borders and break those barriers which were formerly narrowed to mainly the U.S theatrical reality. In this milieu, the rise of social media; namely, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, have facilitated both the performers’ and the spectators’ re/viewings since the former can re/present and promote their neo-burlesque pieces as well as advertise their campaigns and products increasing in this way their popularity while the latter, in their turn, can be informed about the performers’ recent activities, purchase goods or follow their accounts as evidence of support or even condemnation. Moreover, YouTube has revolutionized spectatorship since neo-burlesque performers of versatile performing styles, age, race and body sizes launch their work in order to gain popular appeal through the gathering of views claiming in this way an increase of paychecks and attendance to distinguished events and venues. -

Diane Arbus : a Printed Retrospective, 1960–1971

Pierre Leguillon features Diane Arbus : A Printed Retrospective, 1960–1971 December 6, 2008 — February 8, 2009 Press presentation: Friday, December 5 at 11am Public opening: Friday, December 5, from 6 to 9pm KADIST ART FOUNDATION OPENING HOURS: (0Y`j$)(il\[\jKif`j=i i\j From Thursday to Sunday, from 2pm to 7pm .,'(/GXi`j$=iXeZ\ k\c%&]Xo1"**' (+),(/*+0 or by appointement. nnn%bX[`jk%fi^&ZfekXZk7bX[`jk%fi^ PRESSE KIT / CONTENT 3 Press release 4/5 Presentation of the exhibition 6 Biographies: Diane Arbus, Pierre Leguillon 7/14 Magazine Pages 15/17 List of photographs presented in the exhibition 18 Presentation of Kadist Art Foundation - Upcoming program KADIST ART FOUNDATION (0Y`j$)(il\[\jKif`j=i i\j$.,'(/GXi`j$=iXeZ\$k\c%&]Xo1"**' (+),(/*+0$nnn%bX[`jk%fi^&ZfekXZk7bX[`jk%fi^ PRESSE RELEASE Pierre Leguillon features Diane Arbus : A Printed Retrospective, 1960–1971 December 6, 2008 — February 8, 2009 Press presentation: Friday, December 5 at 11am Public opening: Friday, December 5, from 6 to 9pm At Kadist Art Foundation Pierre Leguillon presents the first retrospective of the works of Diane Arbus (1923–1971) organized in France since 1980, bringing together all the images commissioned to the New York photographer by the Anglo-American press in the 1960s. The exhibition will present the original pages of the magazines, including ‘Harper’s Bazaar’, ‘Esquire’, ‘Nova’ and ‘The Sunday Times Magazine’. Always conceived specifically by Diane Arbus for the press medium, these photographs are showcased in their ori- ginal format for the first time. This private collection consists of more than 150 photographs, demonstrating Diane Arbus’ discreet point of view through a great variety of subjects: reportage, anonymous or celebrity portraits (Norman Mailer, Jorge Luis Borges, Lilian et Dorothy Gish, Mia Farrow, Marcello Mastroianni, Madame Martin Luther King...), chil- dren’s fashion, and several « photographic essays », with captions or comments by the photographer herself.