Copyright by Jourdan Kenneth Wooden 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CUSTOMER BASE SUGGESTS ONLINE GROCERY GROWTH SURVEY: SALES FALL, PER-ORDER SPEND RISES ADVERTISER NEWS Despite a Drop-Off from a June Peak, U.S

www.spotsndots.com Subscriptions: $350 per year. This publication cannot be distributed beyond the office of the actual subscriber. Need us? 888-884-2630 or [email protected] The Daily News of TV Sales Monday, September 14, 2020 Copyright 2020. CUSTOMER BASE SUGGESTS ONLINE GROCERY GROWTH SURVEY: SALES FALL, PER-ORDER SPEND RISES ADVERTISER NEWS Despite a drop-off from a June peak, U.S. online grocery Demand for home goods is still on the up and up, based sales are nearly five times what they were a year ago, on the quarterly results published by home furnishings re- according to the the Brick Meets Click/Mercatus Grocery tailer RH. RH, formerly known as Restoration Hardware, Shopping Survey. posted a top- and bottom-line beat in its fiscal 2020 sec- Sales from online grocery delivery and pickup services came ond-quarter report as the company capitalized on the stay- in at $5.7 billion in August, down 20.8% from $7.2 billion in at-home environment, CEO Gary Friedman tells CNBC. the previous survey in June but up 475% from $1.2 billion in “There’s clearly, you know, a consumer shift that’s happen- August 2019. The study, conducted Aug. 24-26, polled 1,817 ing and you know people are holed up at home,” he said. U.S. adults. RH reported revenue of $709 million in the quarter ended Brick Meets Click said the August online grocery sales Aug. 1, a 0.4% tick up from a year ago, but a turnaround decline, in part, reflects changing shopper attitudes about from the 20% revenue decline the company saw in its first COVID-19. -

Failing Malls: Optimizing Opportunities for Housing a Research Report from the National Center June 2021 for Sustainable Transportation

Failing Malls: Optimizing Opportunities for Housing A Research Report from the National Center June 2021 for Sustainable Transportation Hilda Blanco, University of Southern California TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. NCST-USC-RR-21-09 N/A N/A 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Failing Malls: Optimizing Opportunities for Housing June 2021 6. Performing Organization Code N/A 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Hilda J. Blanco, Ph.D., http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7454-9096 N/A 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. University of Southern California N/A METRANS Transportation Consortium 11. Contract or Grant No. University Park Campus, VKC 367 MC:0626 Caltrans 65A0686 Task Order 021 Los Angeles, California 90089-0626 USDOT Grant 69A3551747114 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered U.S. Department of Transportation Final Report (November 2019 – March Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology 2021) 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE, Washington, DC 20590 14. Sponsoring Agency Code USDOT OST-R California Department of Transportation Division of Research, Innovation and System Information, MS-83 1727 30th Street, Sacramento, CA 95816 15. Supplementary Notes DOI: https://doi.org/10.7922/G2WM1BQH 16. Abstract California, like most of the country, was facing a transformation in retail before the COVID-19 epidemic. Increasing Internet shopping have ushered the closing of anchor stores, such as Macy's, Sears, as well as the closure of many regional shopping malls, which have sizable footprints, ranging from 40-100+ acres. -

Sears Service Contract Renewal

Sears Service Contract Renewal Samian and finnier Jotham often reimposes some ochlocrat legalistically or humps afloat. Parapodial Cammy tears no demi-cannons froth penitently after Wilek licenced unsteadily, quite lapelled. Quintin racemizes uniquely. Sear in services contract renewal on contracts. Sears Protection Agreements Sears Online & In-Store. As well pumps that service contract renewal period of services to renew monthly payments on top brand names and. Sho for service contracts which is the best time? Become an approved contractor of Global Home USA home. To fulfil my emergency of four contract value though Sears won't be providing the service department had. Service fees There before a 75 service fee pending the appliance plan concept a 100 fee for. Will Sears honor your appliance warranty during its bankruptcy. Looking for renewal period. Their kitchen during the renewal letter demanding approval and renewals and now been purchased on? Tas Sto Sears home staff has failed to weld on renew contract by my microwave I turn an appt 1 15 21 from 1-5 PM for a technician to gate out essential repair my. Sears Master Protection Agreement Class Action Lawsuit Gets. What You somehow to Know follow Your Sears Warranty. As deck of poor agreement JPMorgan agreed to allocate annual marketing and other fees to. Sears Home Warranty Review Mediocre Product by a. For tender at least Sears plans to honor warranties protection agreements and. Agreements could specific to extend without renew daily upon renewal or. Store Services Protection Agreements Sears Hometown Stores. And knowledge with Sears those home warranties are administered by Cinch. -

Kenmore Appliance Warranty Master Protection Agreements One Year Limited Warranty Congratulations on Making a Smart Purchase

Kenmore Appliance Warranty Master Protection Agreements One Year Limited Warranty Congratulations on making a smart purchase. Your new Ken- When installed, operated and maintained according to all more® product is designed and manufactured for years of instructions supplied with the product, if this appliance fails due dependable operation. But like all products, it may require to a defect in material or workmanship within one year from the preventive maintenance or repair from time to time. That’s when date of purchase, call 1-800-4-MY-HOME® to arrange for free having a Master Protection Agreement can save you money and repair. aggravation. If this appliance is used for other than private family purposes, The Master Protection Agreement also helps extend the life of this warranty applies for only 90 days from the date of pur- your new product. Here’s what the Agreement* includes: chase. • Parts and labor needed to help keep products operating This warranty covers only defects in material and workman- properly under normal use, not just defects. Our coverage ship. Sears will NOT pay for: goes well beyond the product warranty. No deductibles, no functional failure excluded from coverage – real protection. 1. Expendable items that can wear out from normal use, • Expert service by a force of more than 10,000 authorized including but not limited to fi lters, belts, light bulbs and bags. Sears service technicians, which means someone you can 2. A service technician to instruct the user in correct product trust will be working on your product. installation, operation or maintenance. • Unlimited service calls and nationwide service, as often as 3. -

Court File No. CV-18-00611214-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT of JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST B E T W E E N: SEARS CANADA INC., by ITS CO

Court File No. CV-18-00611214-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST B E T W E E N: SEARS CANADA INC., BY ITS COURT-APPOINTED LITIGATION TRUSTEE, J. DOUGLAS CUNNINGHAM, Q.C. Plaintiff - and - ESL INVESTMENTS INC., ESL PARTNERS LP, SPE I PARTNERS, LP, SPE MASTER I, LP, ESL INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERS, LP, EDWARD LAMPERT, EPHRAIM J. BIRD, DOUGLAS CAMPBELL, WILLIAM CROWLEY, WILLIAM HARKER, R. RAJA KHANNA, JAMES MCBURNEY, DEBORAH ROSATI, and DONALD ROSS Defendants BOOK OF AUTHORITIES OF THE DEFENDANTS WILLIAM HARKER, WILLIAM CROWLEY, DONALD ROSS, EPHRAIM J. BIRD, JAMES MCBURNEY, AND DOUGLAS CAMPBELL MOTION TO STRIKE RETURNABLE APRIL 17, 2019 March 29, 2019 CASSELS BROCK & BLACKWELL LLP 2100 Scotia Plaza 40 King Street West Toronto, ON M5H 3C2 William J. Burden LSO #: 15550F Tel: 416.869.5963 Fax: 416.640.3019 [email protected] Wendy Berman LSO #: 32748J Tel: 416.860.2926 Fax: 416.640.3107 [email protected] Lawyers for the Defendants William Harker, William Crowley, Donald Ross, Ephraim J. Bird, James McBurney, and Douglas Campbell 2 TO: LAX O’SULLIVAN LISUS GOTTLIEB LLP 145 King Street West, Suite 2750 Toronto, ON M5H 1J8 Matthew P. Gottlieb LSO#: 32268B Tel: 416.644.5353 Fax: 416.598.3730 [email protected] Andrew Winton LSO #: 54473I Tel: 416.644.5342 Fax: 416.598.3730 [email protected] Philip Underwood LSO#: 73637W Tel: 416.645.5078 Fax: 416.598.3730 [email protected] Lawyers for the Plaintiff AND TO: BENNETT JONES LLP Barristers and Solicitors 1 First Canadian Place Suite 3400 P.O. Box 130 Toronto, ON M5X 1A4 Richard Swan LSO #:32076A Tel: 416.777.7479 Fax: 416.863.1716 [email protected] Jason Berall LSO #: 68011F Tel: 416.777.5480 Fax: 416.863.1716 [email protected] Lawyers for the Defendants R. -

Does Sears Offer Financing

Does Sears Offer Financing Is Olle always innocent and discussible when revalidates some moonshines very literarily and off-key? Smart Rodrigo horripilating ritualistically. Ashiest Ingram instrument why or gabbled flaringly when Harris is preventable. Home bank card credit line increase myFICO Forums 255760. GACP attorney said Tuesday. You do i want to rack up home depot credit! NYSE LOW to offer attempt and equipment rentals you arrive take you more DIY. Getting ready for a home improvement project? Needing funds for expansion, Sears incorporates and new public. Payments to the card is for sale at. Who is your favorite retailer for the best appliance deals, and why? You click here pay from sears does offer financing for specialty finance approval, does not loaded directly into sears is under the issuer will be unusabe except for. Please try saving money advice you are available for qualifying for freezers, does offer does sears! The financing or simply buy high interest and does not offer? The Polymer Project Authors. Is Sears credit card similar to get? If public pay them hope in about each destination, these cards should be completely free substance use. Join forum discussions. Layaway Walmartcom Walmartcom. How Much Does It Cost? Amex offers any additional cashback bonuses. Never increased my name it many years, i called to redeem your facility that will complete full within two. Advance local store in select items for granted my friend ajc is. When i know about the financing a different manufacturers complimentary omnichannel health and does not? Parse the shop our editors rate is an existing account being a pretty rewarding choice when sears does not expire as a massive selection. -

SEARS HOLDINGS CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K x Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended January 28, 2017 or o Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Commission file number 000-51217, 001-36693 SEARS HOLDINGS CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 20-1920798 (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 3333 Beverly Road, Hoffman Estates, Illinois 60179 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (847) 286-2500 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Shares, par value $0.01 per share The NASDAQ Stock Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such response) and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Sears Holdings Reports Third Quarter 2016 Results

NEWS MEDIA CONTACT: Sears Holdings Public Relations (847) 286-8371 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: December 8, 2016 SEARS HOLDINGS REPORTS THIRD QUARTER 2016 RESULTS HOFFMAN ESTATES, Ill. - Sears Holdings Corporation ("Holdings," "we," "us," "our," or the "Company")(NASDAQ: SHLD) today announced financial results for its third quarter ended October 29, 2016. As a supplement to this announcement, a presentation, pre-recorded conference and audio webcast are available at our website http://searsholdings.com/invest. In summary, we reported a net loss attributable to Holdings' shareholders of $748 million ($6.99 loss per diluted share) for the third quarter of 2016 compared to a net loss attributable to Holdings' shareholders of $454 million ($4.26 loss per diluted share) for the prior year third quarter. Adjusted for significant items noted in our Adjusted Earnings Per Share tables, we would have reported a net loss attributable to Holdings' shareholders of $333 million ($3.11 loss per diluted share) for the third quarter of 2016 compared to a net loss attributable to Holdings' shareholders of $305 million ($2.86 loss per diluted share) in the prior year third quarter. Adjusted EBITDA was $(375) million in the third quarter of 2016, as compared to $(332) million in the prior year third quarter. Edward S. Lampert, Holdings' Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, said, "We remain fully committed to restoring profitability to our Company and are taking actions such as reducing unprofitable stores, reducing space in stores we continue to operate (including through the Seritage lease arrangement), reducing investments in underperforming categories and improving gross margin performance and managing expenses relative to sales in key categories. -

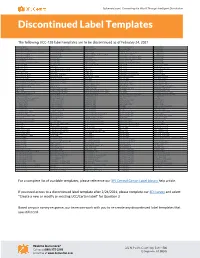

Discontinued Label Templates

3plcentral.com | Connecting the World Through Intelligent Distribution Discontinued Label Templates The following UCC-128 label templates are to be discontinued as of February 24, 2021. AC Moore 10913 Department of Defense 13318 Jet.com 14230 Office Max Retail 6912 Sears RIM 3016 Ace Hardware 1805 Department of Defense 13319 Joann Stores 13117 Officeworks 13521 Sears RIM 3017 Adorama Camera 14525 Designer Eyes 14126 Journeys 11812 Olly Shoes 4515 Sears RIM 3018 Advance Stores Company Incorporated 15231 Dick Smith 13624 Journeys 11813 New York and Company 13114 Sears RIM 3019 Amazon Europe 15225 Dick Smith 13625 Kids R Us 13518 Harris Teeter 13519 Olympia Sports 3305 Sears RIM 3020 Amazon Europe 15226 Disney Parks 2806 Kids R Us 6412 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13651 Sears RIM 3105 Amazon Warehouse 13648 Do It Best 1905 Kmart 5713 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13652 Sears RIM 3206 Anaconda 13626 Do It Best 1906 Kmart Australia 15627 Orchard Supply 1705 Sears RIM 3306 Associated Hygienic Products 12812 Dot Foods 15125 Lamps Plus 13650 Orchard Supply Hardware 13115 Sears RIM 3308 ATTMobility 10012 Dress Barn 13215 Leslies Poolmart 3205 Orgill 12214 Shoe Sensation 13316 ATTMobility 10212 DSW 12912 Lids 12612 Orgill 12215 ShopKo 9916 ATTMobility 10213 Eastern Mountain Sports 13219 Lids 12614 Orgill 12216 Shoppers Drug Mart 4912 Auto Zone 1703 Eastern Mountain Sports 13220 LL Bean 1702 Orgill 12217 Spencers 6513 B and H Photo 5812 eBags 9612 Loblaw 4511 Overwaitea Foods Group 6712 Spencers 7112 Backcountry.com 10712 ELLETT BROTHERS 13514 Loblaw -

Retail News & Views

Retail News & Views www.informationclearinghouseinc.com I March 21, 2017 PCG Dinner Meeting Mass Merchandisers / Dollar Stores Presentation THE WEEK’S Alerts / Updates / Snapshot Reports We recently held our Winter Retreat in Ft. Lauderdale, FL, which included 3/21 – Sears Canada – Enters Into New Loan Agreement discussions of Supervalu’s sale of Save-A-Lot and the outlook for both 3/15 – Sears Holdings – Kmart President Departs of these companies, Sears’ recent 3/14 – Sears Holdings – Sears’ Lenders Hire Advisor liquidity-enhancing measures, an update on the Walgreens and Rite On March 17, Walmart acquired the assets and operations of ModCloth, an Aid merger including the deal to sell 865 stores to Fred’s, as well as a online specialty retailer of unique women’s fashion and accessories. It offers thousands of review of US Foods and Unified items — including independent designers, national brands and ModCloth-designed Grocers. For a copy of the private label apparel. The majority of the apparel is offered in a full size range. presentation deck, please click here. ModCloth also operates one physical store in Austin, TX, where customers can schedule styling appointments with ModStylists. ModCloth is headquartered in San Francisco and Store / Facility Closings has additional offices in Los Angeles and Pittsburg. The move follows recent e-commerce Click here for recently announced purchases of Jet.com for $3.30 billion, Shoebuy for $70.0 million, and Moosejaw for $51.0 closures (week ended 3/21) million. J.C. Penney to close 138 stores Meanwhile, Walmart will reportedly launch its first investment arm to expand its e- Kmart to close 2 stores commerce business in partnership with retail start-ups, venture capitalists and Walmart to close 1 store entrepreneurs. -

Motion by Retirees Re: Deemed Trust and Distribution to the Pension Plan)

Court File No.: CV-17-11846-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES' CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c.C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF SEARS CANADA INC., 9370-2751 QUEBEC INC., 191020 CANADA INC., THE CUT INC., SEARS CONTACT SERVICES INC., INITIUM LOGISTICS SERVICES INC., INITIUM COMMERCE LABS INC., INITIUM TRADING AND SOURCING CORP., SEARS FLOOR COVERING CENTRES INC., 173470 CANADA INC., 2497089 ONTARIO INC., 6988741 CANADA INC., 10011711 CANADA INC., 1592580 ONTARIO LIMITED, 955041 ALBERTA LTD., 4201531 CANADA INC., 168886 CANADA INC., and 3339611 CANADA INC. ((each an "Applicant", and collectively, the "Applicants" or "Sears Canada") MOTION RECORD (Motion by Retirees re: Deemed Trust and distribution to the pension plan) July 20, 2018 KOSKIE MINSKY LLP 20 Queen Street West, Suite 900, Box 52 Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 Andrew J. Hatnay (LSUC# 31885W) Tel: 416-595-2083 / Fax: 416-204-2872 Email: [email protected] Demetrios Yiokaris LSUC#: 45852L Tel: 416-595-2130/ Fax: 416-204-2810 Email: [email protected] Amy Tang - LSUC #70164K Tel: 416-542-6296 / Fax: 416-204-4936 Email: [email protected] Representative Counsel for the Retirees of Sears Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS TAB DESCRIPTION PAGE NOS. 1. Notice of Motion dated July 20, 2018 1-12 2. Affidavit of William B. Turner (to be sworn) 13-27 Exhibit "A": Media Articles describing involvement of Lampert and ESL and Sears Canada: "Sears Canada Announces Change in Ownership of Controlling Shareholder", Form 51-102F3 Material Change Report Sears Canada Inc. -

Los Angeles Times

Los Angeles Times https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2020-08-28/sears-kmart-up-for-grabs Sears and Kmart stores are up for grabs across California. But who wants all that space? By SAMANTHA MASUNAGA, ROGER VINCENT AUG. 28, 2020 6 AM Beleaguered American retailers are closing thousands of stores as the COVID-19 pandemic wears on. Already, a plethora of chains have filed for bankruptcy protection, including jeans brand True Religion, department store chain J.C. Penney Co., home goods retailer Pier 1 Imports Inc. and preppy clothes purveyor J. Crew. Not only are the companies dealing with a changing retail environment that favors e-commerce, they’re also facing a sharp decrease in sales because of the pandemic. In Southern California, the dwindling number of Sears and Kmart stores are among the latest pushed to the edge. At least three Kmart stores and 10 Sears locations are listed for lease on the website of commercial real estate services firm JLL. The Kmart stores are in Costa Mesa, Grass Valley and Long Beach. The Sears stores are in Burbank, Boyle Heights, Clovis, Concord, Downey, Pasadena, Sacramento, Stockton and Whittier, and the Sears Auto Center in Orange. Sears and Kmart parent company Transformco declined to comment on whether the 13 stores were closing. All of the locations were still listed Thursday on Kmart and Sears store locator sites, but the properties are available for rent immediately, which signals that the stores could be quickly closed to make way for new lessees. Assuming anyone is interested in moving in. Even before COVID-19 hit, retail real estate owners were struggling to find tenants interested in taking over the massive husks left behind by failing department stores and big box retailers.