Dog Bite Investigation Worksheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Before You Get Your Puppy” by Ian Dunbar

BEFOREYouBEFORE Get Your Puppy Dr. Ian Dunbar James & Kenneth PUBLISHERS Omaha BEFORE You Get Your Puppy © 2001 Ian Dunbar First published in 2001 by: James & Kenneth Publishers 2140 Shattuck Avenue #2406 Berkeley, California 94704 1-800-784-5531 James & Kenneth—UK Cathargoed Isaf, Golden Grove Carmarthen, Dyfed SA32 8LY 01558-823237 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used in reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher. IBSN 1-888047-00-3 Reprinted by www.dogstardaily.com with permission of the author Dr. Ian Dunbar and James & Kenneth Publishers. This pdf may be duplicated and distributed for free. Contents Foreword...............................................6 Synopsis................................................8 Chapter One: Chapter Four: DEVELOPMENTAL DEADLINES ..12 ERRORLESS HOUSETRAINING....54 1. Your Doggy Education ...................17 When You Are Not at Home...............55 2. Evaluating Puppy's Progress ..........18 Long-term Confinement .....................57 3. Errorless Housetraining ..................19 When You Are at Home......................57 4. Socialization with People ...............20 Short-term Confinement .....................58 5. Bite Inhibition.................................21 Train Your Puppy to Train Himself....60 6. Preventing Adolescent Problems....22 Errorless Housetraining ......................60 Housetraining 1-2-3............................61 Chapter Two: So What's -

Pine Shadows Imprinting

® Today’s Breeder A Nestlé Purina Publication Dedicated to the Needs of Canine Enthusiasts Issue 73 BREEDER PROFILE Pine Shadows Kennel Sunup’s Kennels Warming Up Winter Learning the Ropes Rare Breeds at Purina Farms I especially enjoyed your article Edelweiss-registered dogs have “The Heyday of St. Louis Dog Shows” competed in conformation since the in Issue 72. The Saint Bernard pic- kennel began in 1894. tured winning Best in Show at the Thank you for bringing back mem- 1949 Mississippi Valley Kennel Club ories from our past. Dog Show is CH Gero-Oenz V. Edel - Kathy Knoles weiss, owned and han- Edelweiss Kennels dled by Frank Fleischli, Springfield, IL the second-generation Pro Club members Suzy and Chris owner of Edelweiss Ken - I loved reading about David Holleran feed their Bulldogs, nels. This dog won three Fitzpatrick and the Peke “Malachy” Michelle Gainsley poses her Pekingese, H.T. “Sassy,” above, and “Punkin’,” Bests in Show and the in Issue 72 of Today’s Breeder. I also Purina Pro Plan dog food. feed Purina Pro Plan to my Peke, H.T. Satin Doll, after going Best of Winners at the National Specialty before 2010 Pekingese Club of America National Satin Doll, or “Dolly.” In October, Thank you, Purina, for being blinded in a BB Specialty. “Dolly” also went Best of Opposite Sex. Dolly went Winners Bitch, Best of making Purina Pro Plan gun accident. Winners and Best of Opposite Sex I have been told by other exhibitors dog food. We are Walkin’ I am Frank’s grand- at the Pekingese National in New how wonderful Dolly’s coat is. -

New Jersey Animal Guidelines

New Jersey Animal Guidelines: Any of the following animals owned, kept by, in the care, custody or control of any occupants of the home are ineligible: 1. Any animal deemed dangerous, vicious or potentially dangerous under state statute. 2. Any exotic animal, wild or zoo animals (including but not limited to reptiles, primates, exotic cats and fowl). 3. Any of the following dogs: • Akita Inu • German Shepherd • Alaskan Malamute • Giant Schnauzer • American Bull Dog • Great Dane • American Eskimo Dog (member of the • Gull Dong (aka Pakistani Bull Dog) Spitz Family) • American Staffordshire Terrier • Gull terrier • American Put Bull Terrier • Husky or Siberian Husky • Beauceron • Japanese Tosa/Tosa Inu/Tosa Ken • Boerboel • Korean Jindo • Bull Mastiff/American Bandogge/Bully • Perro de Presa Canario Kutta (any other Mastiff breed) • Cane Corso • Perro de Presa Mallorquin • Caucasian Ovcharka (Mountain Dog) • “Pit Bull” • Chow Chow • Rottweiler • Doberman Pinsher (other than a • Rhodesian Ridgeback miniature Doberman • Dogo Argentino • Staffordshire Bull Terrier • English Bull Terrier • Thai Ridgeback • Fila Brasileiro (aka Brazilian Mastiff) • Wolf or Wolf Hybrid Or any mixed breed dog containing any of the aforementioned breeds. 4. A dog that has been trained as and/or used as a guard dog or attack dog. 5. A dog that has been trained or used by the military or police for enforcing public order by chasing and holding suspects by the threat of being released, either by direct apprehension or a method known as “Bark and Hold”. 6. A dog belonging to a breed that was historically bred for fighting. 7. A dog that has bitten anyone or has exhibited aggressive behavior towards people. -

Dog Bite Prevention

www.dog-bite-prevention.com Page 1 3/23/2005 How to Stop Your Puppy or Older Dog from Biting World Class Trainers Tips To Raising a Well Behaved Dog. Compiled by Lateef Olajide www.dog-bite-prevention.com http://aggressive-dog-behavior-training.blogspot.com www.dog-bite-prevention.com Page 2 3/23/2005 How to Stop Your Puppy or Older Dog from Biting. (c) 2005 Success Brothers Enterprises. No part of this book may be reproduced or redistributed in any form or by any means. Making copies of any part of this book for any purpose other than your own personal use is a violation of United States and international copyright laws. www.dog-bite-prevention.com Page 3 3/23/2005 Dedicated To All Dog Attack Victims. www.dog-bite-prevention.com Page 4 3/23/2005 CONTENT Reasons Why Puppy Bite. ………………………………….…. 7 Dog Bite: The underlying causes. ………………………………. 12 How to recognize warning signs? ………………………………..14 How you can get a puppy to stop biting ..………………………. 16 More on puppy biting: Stop Puppy from Biting. Puppy Biting - Have Patience My Puppy Keeps Chewing What Do I Do? Teaching Puppies Not To Bite How To Prevent Dog Bites: ………………………………………27 Preventive measures applicable to potential dog owners. Preventive measures for dog owners. Preventive measures for parents. Preventive measures for general Adults. How to Socialize - Critical stage for puppy …………………….. 31 www.dog-bite-prevention.com Page 5 3/23/2005 More on Socialization Techniques: Puppy Dog Socialization. Dog Bite Injury prevention - Socialization tips for Puppy owners. Seven things you should do if your dogs bite…. -

Genetics of Canine Behavior

ACTA VET. BRNO 2007, 76: 431-444; doi:10.2754/avb200776030431 Review article Genetics of Canine Behavior K.A. HOUPT American College of Veterinary Behaviorists, Animal Behavior Clinic, Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA Received February 6, 2007 Accepted June 5, 2007 Abstract Houpt K.A.: Genetics of Canine Behavior. Acta Vet. Brno 2007, 76: 431-444. Canine behavioral genetics is a rapidly moving area of research. In this review, breed differences in behavior are emphasized. Dog professionals’ opinions of the various breeds on many behavior traits reveal factors such as reactivity, aggression, ease of training and immaturity. Heritability of various behaviors – hunting ability, playfulness, and aggression to people and other dogs – has been calculated. The neurotransmitters believed to be involved in aggression are discussed. The gene for aggression remains elusive, but identifi cation of single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with breed-specifi c behavior traits are leading us in the right direction. The unique syndrome of aggression found in English Springer Spaniels may be a model for detecting the gene involved. Dog aggression, heritability, temperament Behavior is a result of nature (genetics) and nurture (learning or experience). We shall review the history of canine behavioral genetics and explore the latest fi ndings. The publication of the canine genome allows us to make some inferences (Kirkness et al. 2003). Foxes One of the most thorough studies of canid behavioral genetics deals with foxes, not dogs. Selection for a tame and for an aggressive strain of silver foxes over 30 years by Dmitry Belyaev and Lyudmila Trut resulted in large differences in behavior and in morphology (Trut et al. -

Everything You Need to Know About Pit Bulls, and More!

Pit Bulls: A Guide Everything you need to know about pit bulls, and more! Getting to know the breeds The term "pit bull" applies to several different breeds of medium-sized fighting terriers originally created through experimental crosses with bulldogs and terriers, originating in the 18th and 19th century Europe and America. The aim of these crosses was to combine the strength and bite of a bulldog with the athleticism, gameness, and courage of a terrier to create an all-purpose farm dog that could catch and drive cattle and hogs, clear the barn of vermin, hunt, and just do miscellaneous frontier era ranching tasks while also being a great family companion and babysitter for the kids. Later, especially after the banning of bull baiting as a sport, the focus was taken off of them as all-purpose farm dogs and they were developed and standardized as the fighting dogs we know them as today. These breeds include: The American Pit Bull Terrier: The APBT is what one generally thinks of when they think "pit bull." They are a moderate, medium sized dog that should weigh between 20 and 55 pounds, though the preferred range is probably closer to 35-50 pounds. They are happy, cheerful, athletic, eager to please goofballs that love everyone but can work their butts when called on to do so. This is why they make awesome search and rescue or hunting dogs. This breed is the original Bull and Terrier, the dog that started it all, created from crosses of old-school bulldogs and English White Terriers and standardized in 1898. -

Title III Regulations

NOTICE: The title III regulation was modified by the Pool Extension Final Rule, the ADA Amendments Act Final Rule, and the Movie Captioning and Audio Description Final Rule, which can be found in the Title III Regulation Supplement. This document and the supplement should be read together for the most up-to-date regulation. Alternatively, the fully updated regulation is available in html. Americans with Disabilities Act Title III Regulations Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability by Public Accommodations and in Commercial Facilities Department of Justice September 15, 2010 Contents 1 Supplementary Information.....………...……... 1 Revised Final Title III Regulation 2 with Integrated Text........................................ 29 2010 Guidance and 3 Section-by-Section Analysis......................... 65 1991 Preamble and 4 Section-by-Section Analysis....................... 199 i ii Department of Justice Title IIIIII Regulations Regulations Supplementary Information Department of Justice Department of Justice Department of Justice 28 CFR Part 36 DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE of Justice, at (202) 307–0663 (voice or TTY). This is not a toll-free number. Information may also be 28 CFR Part 36 obtained from the Department’s toll-free ADA In- formation Line at (800) 514–0301 (voice) or (800) [CRT Docket No. 106; AG Order No. 3181– 514–0383 (TTY). 2010] This rule is also available in an accessible for- mat on the ADA Home Page at http://www.ada. RIN 1190–AA44 gov. You may obtain copies of this rule in large print or on computer disk by calling the ADA In- Nondiscrimination on the Basis of formation Line listed above. Disability by Public Accommodations and in Commercial Facilities SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: AGENCY: Department of Justice, Civil The Roles of the Access Board and the Depart- Rights Division. -

Socialization and Bite Inhibition

SOCIALIZATION AND BITE INHIBITION What is the Socialization Period? √ Between the age of 4-14 weeks your puppy is in her most important developmental stage. √ Within this time, your puppy develops the seek-avoidance blueprint she will use for the rest of her life when encountering novelty. √ Your puppy’s personality will not only be determined by her breed characteristics and parentage but almost equally by her socialization period. √ The experiences your puppy has during this important window of development will directly affect her personality as an adult. How Do I Socialize My Puppy? It is your responsibility to introduce your puppy to as many experiences as possible and to make each experience pleasant. Your puppy runs the risk of being frightened or aggressive toward objects or situations that she was not exposed to or had a scary encounter with during her socialization period. Think of the socialization that you do now as “vaccinating your puppy against scary things”. 1. Your puppy’s thought process is pretty simple: food =good. 2. During your puppy’s socialization period never be without a food treat. Carry them in your pockets, purse, car, baby stroller or backpack. 3. Allow your puppy to approach, investigate and observe new experiences at her own speed. 4. Talk confidently to your puppy when she encounters a new object (something as simple as a leaf blowing across the sidewalk can be scary to a puppy!), person or event and give her one of the many treats you have in your pocket. What Should I Do If My Puppy is Fearful of Something? If your puppy becomes fearful during an encounter be careful about what you may be communicating to her when she is afraid. -

21 Ways to Love Your Swissy Written by Dori Likevich

21 Ways to Love Your Swissy Written by Dori Likevich 1) UNDERSTAND THE BREED. Swissys are categorized in the Working Group of dogs, as are Rottweilers, Akitas, Mastiffs, Saint Bernards, Great Pyrenees, Kuvaszok, Doberman Pinschers and 12 other AKC-recognized breeds. Characteristically, working breeds have a tendency toward displays of dominance in their natures. Dominance is not necessarily a bad trait, if kept in check and channeled into constructive avenues. Dominance can provide a dog with “drive.” Working breeds possess drive. It is what makes them capable of performing the functions for which they were bred. However, if dominant displays are allowed to escalate into acts of aggression, whether toward people or other animals, this inappropriate and dangerous behavior is indicative that the dog is in control and not the human. 2) CRATE TRAIN YOUR SWISSY. One way to exercise control over your Swissy is to establish a crate routine from the time you acquire your Swissy. In fact, the breeder of your Swissy may have already begun crate training with the litter of puppies before they traveled to their new homes. The advantages to crate training a dog are numerous. There are many excellent articles about why you should crate train your dog and how to go about a method of training suitable to you and your lifestyle. One of the best reasons to crate train your Swissy is to hasten the process of housetraining. Swissys are, characteristically, slow to house train. It is not unusual to learn that your Swissy may not be entirely reliable in the house until it is 8 months to 1 year of age. -

Less Than Exciting Behaviors Associated with Unneutered

1 c Less Than Exciting ASPCA Behaviors Associated With Unneutered Male Dogs! Periodic binges of household destruction, digging and scratching. Indoor restlessness/irritability. N ATIONAL Pacing, whining, unable to settle down or focus. Door dashing, fence jumping and assorted escape behaviors; wandering/roaming. Baying, howling, overbarking. Barking/lunging at passersby, fence fighting. Lunging/barking at and fighting with other male dogs. S HELTER Noncompliant, pushy and bossy attitude towards caretakers and strangers. Lack of cooperation. Resistant; an unwillingness to obey commands; refusal to come when called. Pulling/dragging of handler outdoors; excessive sniffing; licking female urine. O UTREACH Sexual frustration; excessive grooming of genital area. Sexual excitement when petted. Offensive growling, snapping, biting, mounting people and objects. Masturbation. A heightened sense of territoriality, marking with urine indoors. Excessive marking on outdoor scent posts. The behaviors described above can be attributed to unneutered male sexuality. The male horomone D testosterone acts as an accelerant making the dog more reactive. As a male puppy matures and enters o adolescence his primary social focus shifts from people to dogs; the human/canine bond becomes g secondary. The limited attention span will make any type of training difficult at best. C a If you are thinking about breeding your dog so he can experience sexual fulfillment ... don’t do it! This r will only let the dog ‘know what he’s missing’ and will elevate his level of frustration. If you have any of e the problems listed above, they will probably get worse; if you do not, their onset may be just around the corner. -

US Police and Citizen Shootings of Pit Bulls 2008

Report: U.S. Police and Citizen Shootings of Pit Bulls 2008 by DogsBite.org | June 1, 2009 Summary: To evaluate the numerous U.S. media reports on pit bulls and their mixes shot for public safety reasons, DogsBite.org and contributor David Monroe recorded these incidences over the 12-month period of 2008. The 20-page report documents 373 incidences that involved dangerous pit bulls shot by U.S. law enforcement officers and citizens. The report tracked 12 data aspects per incident. Of the tracked incidences, 626 bullets were fired and 319 pit bulls were killed. 148 people suffered bite injury in these incidences as well. In at least three instances, the bite injury resulted in amputation. In six instances, the bite injury resulted in death. The findings also show that firearm intervention may have prevented at least eight deaths by a pit bull mauling. Information for this report was gathered through online media sources at the time of the shooting. Through the combination of Google News Alerts and web searches, 373 cited incidences are documented in this report. Additional information about the data collection process and how to access the related source documentation is located on page III. DogsBite.org 4742 42nd Ave SW #267 Seattle, WA 98116 www.dogsbite.org [email protected] DogsBite.org: Some dogs don't let go. I Report: U.S. Police and Citizen Shootings of Pit Bulls 2008 Objectives: 1.) Demonstrate the number of occurrences, the bite injury resulted in death U.S. media reports within a 12-month period including: Isis Krieger, 6 (Anchorage, AK), of law enforcement officers and citizens that Kelli Chapman, 24 (Longville, LA), Luna were forced to shoot a dangerous pit bull to McDaniel, 83 (Ville Platte, LA) Cenedi prevent an attack or to stop an ongoing Carey, 4 months (Las Vegas, NV) Tanner attack. -

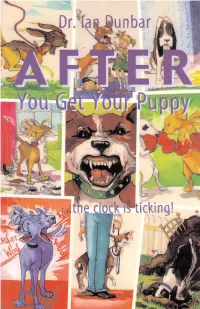

After You Get Your Puppy (PDF)

puppy training AFTER You Get Your Puppy Dr. Ian Dunbar This eBook is provided courtesy of: James & Kenneth PUBLISHERS AFTER YOU GET YOUR PUPPY The Remaining Three Developmental Deadlines The 4th Developmental Deadline Socialization with People The Most Urgent Priority—by 12 weeks of age The 5th Developmental Deadline Learning Bite Inhibition The Most Important Priority—by 18 weeks of age The 6th Developmental Deadline Preventing Adolescent Problems The Most Enjoyable Priority—by five months of age The most urgent priority is to socialize your puppy to a wide variety of people, especially children, men, and strangers, before he is twelve weeks old. Well-socialized puppies grow up to be wonderful companions, whereas antisocial dogs are difficult, time-consuming, and potentially dangerous. Your puppy needs to learn to enjoy the company of all people and to enjoy being handled by all people, especially children and strangers. As a rule of thumb, your puppy needs to meet at least a hundred people before he is three months old. Since your puppy is still too young to venture out on the streets, you'll need to start inviting people to your home right away. Basically, you'll need to have lots of puppy parties and invite friends over to handfeed your pup and train him for you. www.dogstardaily.com 6 DEVELOPMENTAL DEADLINES The most important priority is that your puppy learns reliable bite inhibition and develop a soft mouth before he is eighteen weeks old. Whenever a dog bites a person or fights with another dog, the seriousness of the problem depends on the seriousness of the injury.