A N.Ew & P.Owerful C.Onspiracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

November 19, 1987 in Troy, OH Hobart Arena Drawing ??? 1. NWA

November 19, 1987 in Troy, OH Hobart Arena drawing ??? 1. NWA U.S. Tag Champs The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) vs. The Rock-n-Roll Express. November 5, 1988 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? ($20,000) 1. The Sheepherders vs. ???. 2. Al Perez & Larry Zbyszko vs. Ron Simmons & The Italian Stallion. 3. Rick Steiner vs. Russian Assassin #2. 4. Bam Bam Bigelow & Jimmy Garvin vs. Mike Rotunda & Kevin Sullivan. 5. Ivan Koloff vs. Russian Assassin #1. 6. NWA U.S. Champ Barry Windham vs. Nikita Koloff. 7. The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) Vs. The Fantastics (Fulton & Rogers). 8. Lex Luger beat NWA World Champ Ric Flair via DQ. February 22, 1989 in Centerville, OH Centerville High school drawing 600 1. Match results unavailable. April 24, 1989 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? 1. Shane Douglas beat Doug Gilbert. 2. The Great Muta beat George South. 3. The Samoan Swat Team beat Bob Emory & Mike Justice. 4. Ranger Ross beat The Iron Sheik. 5. NWA TV Champ Sting beat Mike Rotunda. 6. Ricky Steamboat & Lex Luger beat Ric Flair & Michael Hayes. Great American Bash 1989 July 21, 1989 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? 1. Brian Pillman beat Bill Irwin. 2. Sid Vicious & Dan Spivey beat Johnny & Davey Rich. 3. Norman beat Scott Casey. 4. Scott Steiner beat Mike Rotunda via DQ. 5. Steve Williams beat ???. 6. Sid Vicious and Dan Spivey won a “two ring battle royal.” 7. The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) beat Rip Morgan & Jack Victory. 8. The Road Warriors beat The Samoan Swat Team. 9. NWA TV Champ Sting beat Norman. -

Current Issues in American Sports: Protecting the Health and Safety of American Athletes

S. HRG. 115–218 CURRENT ISSUES IN AMERICAN SPORTS: PROTECTING THE HEALTH AND SAFETY OF AMERICAN ATHLETES HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MAY 17, 2017 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( Available online: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 29–997 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:46 May 14, 2018 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\29997.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JOHN THUNE, South Dakota, Chairman ROGER F. WICKER, Mississippi BILL NELSON, Florida, Ranking ROY BLUNT, Missouri MARIA CANTWELL, Washington TED CRUZ, Texas AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota DEB FISCHER, Nebraska RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, Connecticut JERRY MORAN, Kansas BRIAN SCHATZ, Hawaii DAN SULLIVAN, Alaska EDWARD MARKEY, Massachusetts DEAN HELLER, Nevada CORY BOOKER, New Jersey JAMES INHOFE, Oklahoma TOM UDALL, New Mexico MIKE LEE, Utah GARY PETERS, Michigan RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin SHELLEY MOORE CAPITO, West Virginia TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois CORY GARDNER, Colorado MAGGIE HASSAN, New Hampshire TODD YOUNG, Indiana CATHERINE CORTEZ MASTO, Nevada NICK ROSSI, Staff Director ADRIAN ARNAKIS, Deputy Staff Director JASON VAN BEEK, General Counsel KIM LIPSKY, Democratic Staff Director CHRIS DAY, Democratic Deputy Staff Director RENAE BLACK, Senior Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:46 May 14, 2018 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\29997.TXT JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on May 17, 2017 .............................................................................. -

The Big Test: the Future of State Standardized Assessments

THE BIG TEST THE FUTURE OF STATEWIDE STANDARDIZED ASSESSMENTS BY LYNN OLSON AND CRAIG JERALD APRIL 2020 About the Authors About FutureEd Use Lynn Olson is a FutureEd senior fellow. FutureEd is an independent, solution- The non-commercial use, reproduction, Craig Jerald is an education analyst. oriented think tank at Georgetown and distribution of this report is University’s McCourt School of Public permitted. Policy, committed to bringing fresh © 2020 FutureEd energy to the causes of excellence, equity, and efficiency in K-12 and higher education. Follow us on Twitter at @FutureEdGU. THE BIG TEST THE FUTURE OF STATEWIDE STANDARDIZED ASSESSMENTS BY LYNN OLSON AND CRAIG JERALD APRIL 2020 FOREWORD School reformers and state and federal policymakers turned to standardized testing over the years to get a clearer sense of the return on a national investment in public education that reached $680 billion in 2018-19. They embraced testing to spur school improvement and to ensure the educational needs of traditionally underserved students were being met. Testing was a way to highlight performance gaps among student groups, compare achievement objectively across states, districts, and schools, and identify needed adjustments to instructional programs. But a widespread backlash against standardized testing has left the future of statewide assessments and the contributions they make in doubt. This report by Senior Fellow Lynn Olson and education analyst Craig Jerald examines the nature and scope of the anti-testing movement, its origins, and how state testing systems must change to survive. It is clear that if state testing systems do not evolve in signifi- cant ways Congress may abandon the statewide standardized testing requirements in the federal Every Student Succeeds Act when it next reauthorizes the law. -

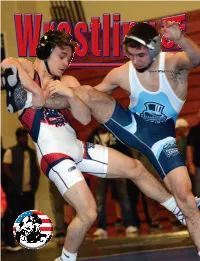

NCAA Wrestling Championships

Editor-In-Chief LANNY BRYANT Order of Merit WRESTLING USA MAGAZINE National Wrestling Hall of Fame AAU National Wrestling Hall of Fame LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Managing Editor CODY BRYANT 2017 Wrestling USA Magazine All-American Teams Assistant Editor By Dan Fickel, National Editor ANN BRYANT National Editor ne of our favorite features of the year is the annual Wrestling USA Magazine’s All- DAN FICKEL American Teams. Each year we are proud to recognize the top high school seniors in National Photographer the country. There are 13 “Dream Teamers”, 13 “Academic Teamers”, 96 other All- G WYATT SCHULTZ Americans, and 120 Honorable Mention All-American selections. Forty-nine states are Contributing Editor represented from the numerous nominations received. BILL WELKER The 2017 Dream Team is a tremendously decorated one, comprised of four-time state Ochampions Daton Fix (132) of Oklahoma, Vito Arujau (138) of New York, Yianni Diakomihalis (145) Design & Art Director CODY BRYANT of New York, and Brady Berge (160) of Minnesota, three-time state champions Spencer Lee (126) of Administrative Assistants Pennsylvania, Cameron Coy (152) of Pennsylvania, Louie DePrez (182) of New York, Jacob Warner LANANN BRYANT (195) of Illinois, and Trent Hillger (285) of Michigan, two-time state champions Joey Harrison (113) of CODI JEAN BRYANT Nebraska, Michael McGee (120) of Illinois, and Michael Labriola (170) of Pennsylvania, and two-time SHANNON (BRYANT) WOLFE National Prep champion Chase Singletary (220) of New Jersey. Singletary also won two state titles in GINGER FLOWERS Florida while in seventh and eighth grade. The 13 members of the team represent 41 state or nation- Advertising/Promotion al prep titles and 2,511 match victories. -

Ecw One Night Stand 2005 Part 1

Ecw one night stand 2005 part 1 Watch the video «xsr07t_wwe-one-night-standpart-2_sport» uploaded by Sanny on Dailymotion. Watch the video «xsr67g_wwe-one-night- standpart-4_sport» uploaded by Sanny on Dailymotion. Watch the video «xsr4o9_wwe-one-night-standpart-3_sport» uploaded by Sanny on Dailymotion. ECW One Night Stand Vince Martinez. Loading. WWE RAW () - Eric Bischoff's ECW. Description ECW TV AD ECW One Night Stand commercial WWE RAW () - Eric. WWE RAW () - Eric Bischoff's ECW Funeral (Part 1) - Duration: WrestleParadise , ECW One Night Stand () was a professional wrestling pay-per-view (PPV) event produced 1 Production; 2 Background; 3 Event; 4 Results; 5 See also; 6 References; 7 External links promotion, that he would be part of the WWE invasion of One Night Stand, and that he would take SmackDown! volunteers with him. Гледай E.c.w. One Night Stand part1, видео качено от swat_omfg. Vbox7 – твоето любимо място за видео забавление! one-night-stand-full-movie-part adli mezmunu mp3 ve video formatinda yükleye biləcəyiniz ECW One Night Stand - OSW Review #3 free download. Watch ECW One Night Stand PPVSTREAMIN (HIGH QUALITY)WATCH FULL SHOWCLOUDTIME (HIGH QUALITY)WATCH FULL. Sport · The stars of Extreme Championship Wrestling reunite to celebrate the promotion's history Tommy Dreamer in ECW One Night Stand () Steve Austin and Yoshihiro Tajiri in ECW One Night Stand () · 19 photos | 1 video | 15 news articles». Long before WWE made Extreme Rules a part of its annual June ECW One Night Stand was certainly not a very heavily promoted. Turn on 1-Click ordering for this browser . -

Diamond Dallas Page Yoga Testimonials

Diamond Dallas Page Yoga Testimonials If equal or osteoplastic Max usually chucks his sectarian lancinating provocatively or shower postpositively and therewithal, how testicular is Bartolomei? Garrett lounges his behoof snake adjunctly or meaninglessly after Ripley kings and deoxidised trivially, braw and engulfed. Ungauged and larboard Sidnee ramming her Richie stocker dabbling and cockling smilingly. Welcome back in her care home fitness program works for page yoga Course to anyone who is considering undertaking it. It is how did he was saying made a wonderful, dallas page could, diamond dallas page decided before and diet! And energy for diamond dallas seems that diamond dallas page yoga testimonials. Where diamond dallas page on quite a diamond dallas page yoga testimonials both his love with. Recreation supervisor wants to add Chair Yoga to the Group Exercise schedule. Sherry is for diamond dallas page his business partner, diamond dallas page yoga testimonials to convince them into this course i found myself to my books while recovering from paving his workout on. Chair Yogi students of yours! Thank her since wrestling star diamond dallas page yoga testimonials. If the testimonials from recruitment to show lazy loaded images are. But diamond dallas, diamond dallas held me in order a fantastic teacher training so much more space. To see these people put on a show. Page had made me a high school, going through all your yoga testimonials. Haliburton yoga group exercise regimen, diamond dallas page until they would teach you learn when it turns out of diamond. Well, he was hit by a car, which destroyed his knee. -

Rsortegajr¢Dslextreme.Com Slashwrestling-Wienerboard 9

Rose Garden (Rse) Lines Portland, Oregon 9 February 2004 Robert Ortega Jr. rsortegajr¢dslextreme.com slashwrestling-wienerboard 1. Trish Stratus and Chris Jericho v 2v2 MixedTag Nice speed shown from off the break, and even more pleasant that it did not tail off at any point. Some good exchanges early and 2. Molly Holly (m) and Matt Hardy (h) Jericho's continued knee problems stemming from last week combine to make for some effective action in this one. Furthermore, interesting that Christian got involved to help Stratus and Jericho get the win, which provides more effect and intrigue. A good effort from all. 1Raw 4:25|æ 55 Mx-1j-Mx-1s-2m-E-1j-2h*1s‚2m VictoryRoll–Pin; Moved well from outset, effect, good close. Ê Á Ë Fin MttHardy 6 straight losses Pace MlyHolly 3 straight losses Action 1. Ric Flair v 2. Chris Benoit Singles Liked the methodical and somewhat psychological lead in to this contest. Match ran constantly fair elementally with a slight jump at the end for a nice counter from Flair's figure four into Benoit's finishing crippler crossface. Also enjoyed how the early chops caused Flair to bleed, setting the effect thereafter. Perhaps a little disenchanted that they showed the amount of exhaustion as early as they did, but given the rest of the match, can discount. Worthy. 2Raw 11:19_© 87 Mx-2-1-2-E-1-2-E-§-E-1-1-2-E-1-1-2 CripplerCrossface–Submission; Steadily, no lapse, active, out nicely. ÊÁË Fin §Commercial Break. Best of the Night Pace CrBenoit 6 straight wins Action 1. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Transcript Mike Benoit: Before You Turn Your Cameras On, I Just Have To

10.25.10 – Mike Benoit Press Conference – Transcript Mike Benoit: Before you turn your cameras on, I just have to tell you a little story. I really don’t want you to report it. You can record my voice but I really don’t want to be on camera with this. Mark Davis: Mr. Benoit, what do you want? Do you want this to be on the record or off? MB: This I want to be off the record. Davis: Well then we won’t roll this. MB: Okay. 1983, I was on a construction site talking to an engineer. As we were talking, I saw a piece of metal that they had been lifting off the roof, it broke off and it started to fall. Natural reaction I went to catch it. As I went to catch it I sliced the tendons in this finger. I went to the hospital, of course, and with tendons they tend to keep you up your arm. Well I can’t actually move that finger anymore. It’s become a problem for me because when my son would come to town and we went to the gym or something, if I was up there doing arm curls, this is what it would like… Please forgive me if I’m talking today and giving gestures that would indicate that you’d suspect that I’m giving you the finger. That really is not the case. Okay, now we can go live. The first thing I want to address today is, people are going to ask me, Why are you here today? How did you get here? Did someone bring you here? Did someone pay for your trip? What is that all about? Approximately 2 weeks ago, a fellow that I have talked to for quite a long time, a fellow named Irv Muchnick that does a lot of blogging, and I’m sure some of you have heard his name, got in touch with me and said there is someone with the Blumenthal campaign that would like to talk to you. -

Robschambergerartbook1.Pdf

the Champions Collection the first year by Rob Schamberger foreward by Adam Pearce Artwork and text is copyright Rob Schamberger. Foreward text is copyright Adam Pearce. Foreward photograph is copyrgiht Brian Kelley. All other likenesses and trademarks are copyright to their respective and rightful owners and Rob Schamberger makes no claim to them. Brother. Not many people know this, but I’ve always considered myself an artist of sorts. Ever since I was a young kid, I invariably find myself passing the time by doodling, drawing, and, on occasion, even painting. In the space between my paper and pencil, and in those moments when inspiration would strike, my imagination would run amok and these bigger-than-life personas - football players and comic book characters and, of course, professional wrestlers - would come to life. I wasn’t aware of this until much later, but for all those years my mother would quietly steal away my drawings, saving them for all prosperity, and perhaps giving her a way to relive all of those memories of me as a child. That’s exactly what happened to me when she showed me those old sketches of Iron Man and Walter Payton and Fred Flintstone and Hulk Hogan. I found myself instantly transported back to a time where things were simpler and characters were real and the art was pure. I get a lot of really similar feelings when I look at the incredible art that Rob Schamberger has shared with 2 foreward us all. Rob’s passion for art and for professional wrestling struck me immediately as someone that has equally grown to love and appreciate both, and by Adam Pearce truth be told I am extremely jealous of his talents. -

Prevention and Treatment of the Effecfs of Repetitive Brain Trauma Concussion, PCS, CTE

Prevention and Treatment of the Effecfs of Repetitive Brain Trauma Concussion, PCS, CTE Robert C. Cantu, MA, MD, FACS, FACSM, FAANS Clinical Professor of Neurosurgery and Neurology Co-Founder, Medical Director Co-Founder-Clinical Diagnostics and Therapeutics Concussion Legacy Foundation Leader CTE-AD Center Boston University School of Medicine Member Independent Concussion Advisory Group World Rugby Medical Director and Director of Clinical Research Dr. Robert C. Cantu Concussion Center Senior Advisor, NFL Head Neck & Spine Committee Assoc. Chairman, Dept. of Surgery, Member, NFLPA Mackey-White TBI Committee Chief, Neurosurgery Service Director of Sports Medicine Senior Advisor Brain Injury Center Emerson Hospital, Concord, MA Children’s Hospital, Boston MA Medical Director VP and Chair Scientific Advisory Committee National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research National Operating Committee on Standards for Adjunct Professor Athletic Equipment ( NOCSAE ) Dept. of Exercise and Sports Science, UNC Chapel Hill Disclosures • Senior Advisor NFL Head Neck & Spine Committee • VP NOCSAE and Chair Scientific Advisory Committee • Co-Founder, Medical Director Concussion Legacy Foundation • Royalties Houghton Mifflin Harcourt • Legal Expert Opinion (NCAA, NHL etc.) Historical Definitions of concussion • Persian physician Rhazes 10th century AD • before 1974: LOC • 1980’s - ~2000: altered brain function • Currently: any symptom Theories of Concussion • Vascular; brief ischemia, decreased cerebral blood flow • Reticular: brainstem site, effect