Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment Austin Nichols, Josh Mitchell, and Stephan Lindner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Misused English Words and Expressions in EU Publications EN

EN 2016 1 EUROPEAN COURT OF AUDITORS Misused English words and expressions in EU publications 2 Preface to the May 2016 edition It has been over two years since I last updated this guide. During this period, I have conducted a number of talks and workshops and have been able to benefit from a good deal of feedback. At the risk of being repetitive, I would once again like to emphasise that I aim neither to criticise the work of EU authors nor to dictate how people should speak or write in their internal or private correspondence. In addition to providing guidance to readers who are unfamiliar with the EU parlance, my comments are mainly designed for those who, for reasons of character or personal taste, would like their English to be as correct as possible1, and those who need, or want, their output to be understood by people outside the European institutions, particularly in our two English-speaking member states. This takes up a principle that is clearly set out in the Court of Auditor’s performance audit manual: ‘In order to meet the addressees’ requirements, reports should be drafted for the attention of an interested but non-expert reader who is not necessarily familiar with the detailed EU [or audit] context’. Roughly translated, this means that we need to be aware of what constitutes our in-house jargon and attempt to avoid it, particularly in documents intended for publication. Of course, if a text is exclusively for internal consumption or it is not necessary for the ‘European citizen’ to be able to understand it, there may be grounds for ignoring the advice below. -

Unemployment Insurance and Macroeconomic Stabilization

153 Unemployment Insurance and Macroeconomic Stabilization Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Harvard University and the National Bureau of Economic Research John Coglianese, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Abstract Unemployment insurance (UI) provides an important cushion for workers who lose their jobs. In addition, UI may act as a macroeconomic stabilizer during recessions. This chapter examines UI’s macroeconomic stabilization role, considering both the regular UI program which provides benefits to short-term unemployed workers as well as automatic and emergency extensions of benefits that cover long-term unemployed workers. We make a number of analytic points concerning the macroeconomic stabilization role of UI. First, recipiency rates in the regular UI program are quite low. Second, the automatic component of benefit extensions, Extended Benefits (EB), has played almost no role historically in providing timely, countercyclical stimulus while emergency programs are subject to implementation lags. Additionally, except during an exceptionally high and sustained period of unemployment, large UI extensions have limited scope to act as macroeconomic stabilizers even if they were made automatic because relatively few individuals reach long-term unemployment. Finally, the output effects from increasing the benefit amount for short-term unemployed are constrained by estimated consumption responses of below 1. We propose five changes to the UI system that would increase UI benefits during recessions and improve the macroeconomic stabilization role: (I) Expand eligibility and encourage take-up of regular UI benefits. (II) Make EB fully federally financed. (III) Remove look-back provisions from EB triggers that make automatic extensions turn off during periods of prolonged unemployment. (IV) Add additional automatic extensions to increase benefits during periods of extremely high unemployment. -

The Neoclassical Economics of Consumer Contracts

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2007 The Neoclassical Economics of Consumer Contracts Richard A. Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Epstein, "The Neoclassical Economics of Consumer Contracts," 92 Minnesota Law Review 803 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exchange The Neoclassical Economics of Consumer Contracts Richard A. Epsteint There is little doubt that the major new theoretical ap- proach to law and economics in the past two decades does not come from either of these two fields. Instead it comes from the adjacent discipline of cognitive psychology, which has now morphed into behavioral economics. Starting with the path- breaking work of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s, the field has asked one question in a thousand guises: do ordinary people obey the principles of rational choice in making their decisions?' The usual answer given in the field is that in at least some domains they do not.2 The new law and economics literature uses these behavioral findings, especially in the study of cognitive bias, to open a new chapter in the long- standing debate over the extent to which market failures pave t The James Parker Hall Distinguished Service Professor of Law, The University of Chicago, and the Peter and Kirsten Bedford Senior Fellow, The Hoover Institution. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern Lima, Gerson P. Macroambiente 3 March 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/63135/ MPRA Paper No. 63135, posted 21 Mar 2015 13:54 UTC Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern Gerson P. Lima1 The present treatise is an attempt to present a modern version of old doctrines with the aid of the new work, and with reference to the new problems, of our own age (Marshall, 1890, Preface to the First Edition). 1. Introduction Many people are convinced that the contemporaneous mainstream economics is not qualified to explaining what is going on, to tame financial markets, to avoid crises and to provide a concrete solution to the poor and deteriorating situation of a large portion of the world population. Many economists, students, newspapers and informed people are asking for and expecting a new economics, a real world economic science. “The Keynes- inspired building-blocks are there. But it is admittedly a long way to go before the whole construction is in place. But the sooner we are intellectually honest and ready to admit that modern neoclassical macroeconomics and its microfoundationalist programme has come to way’s end – the sooner we can redirect our aspirations to more fruitful endeavours” (Syll, 2014, p. 28). Accordingly, this paper demonstrates that current mainstream monetarist economics cannot be science and proposes new approaches to economic theory and econometric method that after replication and enhancement may be a starting point for the creation of the real world economic theory. -

Language Development Language Development

Language Development rom their very first cries, human beings communicate with the world around them. Infants communicate through sounds (crying and cooing) and through body lan- guage (pointing and other gestures). However, sometime between 8 and 18 months Fof age, a major developmental milestone occurs when infants begin to use words to speak. Words are symbolic representations; that is, when a child says “table,” we understand that the word represents the object. Language can be defined as a system of symbols that is used to communicate. Although language is used to communicate with others, we may also talk to ourselves and use words in our thinking. The words we use can influence the way we think about and understand our experiences. After defining some basic aspects of language that we use throughout the chapter, we describe some of the theories that are used to explain the amazing process by which we Language9 A system of understand and produce language. We then look at the brain’s role in processing and pro- symbols that is used to ducing language. After a description of the stages of language development—from a baby’s communicate with others or first cries through the slang used by teenagers—we look at the topic of bilingualism. We in our thinking. examine how learning to speak more than one language affects a child’s language develop- ment and how our educational system is trying to accommodate the increasing number of bilingual children in the classroom. Finally, we end the chapter with information about disorders that can interfere with children’s language development. -

Parental Socioeconomic Status, Child Health, and Human Capital Janet

Parental Socioeconomic Status, Child Health, and Human Capital Janet Currie and Joshua Goodman ABSTRACT Parental socioeconomic status (SES) may affect a child’s educational outcomes through a number of pathways, one of which is the child’s health. This essay asks two questions: What evidence exists about the effect of parental SES on child health? And, what evidence exists about the effect of child health on future outcomes, such as education? We conclude that there is strong evidence of both links. Introduction Investments in education pay off in the form of higher future earnings, and differences in educational attainments explain a significant fraction of the adult variation in wages, incomes, and other outcomes. But what determines a child’s educational success? Most studies point to family background as the primary factor. But why does background matter? While many aspects are no doubt important, research increasingly implicates health as a potentially major factor. The importance of health for education and earnings suggests that if family background affects child health, then poor child health may in turn affect education and future economic status. What evidence exists about the effect of parental socioeconomic status (SES) on child health? And, what evidence exists about the effect of child health on future outcomes, such as education? A great deal of evidence shows that low SES in childhood is related to poorer future adult health (Davey Smith et al., 1998). The specific question at the heart of this review is whether low parental SES affects future outcomes through its effects on child health. In most of the studies cited, SES is defined by parental income or poverty status, though some measure SES through residential neighborhood or parental schooling attainment. -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

A Primer on Modern Monetary Theory

2021 A Primer on Modern Monetary Theory Steven Globerman fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive Summary / i 1. Introducing Modern Monetary Theory / 1 2. Implementing MMT / 4 3. Has Canada Adopted MMT? / 10 4. Proposed Economic and Social Justifications for MMT / 17 5. MMT and Inflation / 23 Concluding Comments / 27 References / 29 About the author / 33 Acknowledgments / 33 Publishing information / 34 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 35 Purpose, funding, and independence / 35 About the Fraser Institute / 36 Editorial Advisory Board / 37 fraserinstitute.org fraserinstitute.org Executive Summary Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a policy model for funding govern- ment spending. While MMT is not new, it has recently received wide- spread attention, particularly as government spending has increased dramatically in response to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and concerns grow about how to pay for this increased spending. The essential message of MMT is that there is no financial constraint on government spending as long as a country is a sovereign issuer of cur- rency and does not tie the value of its currency to another currency. Both Canada and the US are examples of countries that are sovereign issuers of currency. In principle, being a sovereign issuer of currency endows the government with the ability to borrow money from the country’s cen- tral bank. The central bank can effectively credit the government’s bank account at the central bank for an unlimited amount of money without either charging the government interest or, indeed, demanding repayment of the government bonds the central bank has acquired. In 2020, the cen- tral banks in both Canada and the US bought a disproportionately large share of government bonds compared to previous years, which has led some observers to argue that the governments of Canada and the United States are practicing MMT. -

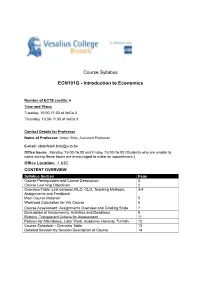

Course Syllabus ECN101G

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates.