An Investigation of Shopping Centres As Situational Influences on Consumer Behaviour in the Greater Durban Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON

THE PROVINCE OF DIE PROVINSIE VAN UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG IN GAUTENG Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2.50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3.25 PRETORIA Vol. 25 27 FEBRUARY 2019 No. 57 27 FEBRUARIE 2019 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1682-4525 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 00057 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 452005 2 No. 57 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, 27 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. CONTENTS GENERAL NOTICE No Page No 380 Gauteng Liqour Act, 2003 (Act No. 2 of 2003): Notice of applications for liquor licences in terms of section 24: Divided into the following regions: ............................................................................................................................................................. 10 Johannesburg ............................................................................................................................................................... 10 Tshwane ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

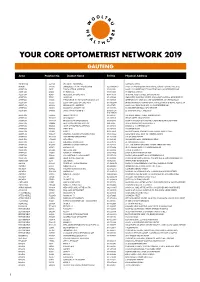

Your Core Optometrist Network 2019 Gauteng

YOUR CORE OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2019 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 9071046 SHOPS -

Mont D'or Bohemian House

FACT SHEET – MONT D’OR BOHEMIAN HOUSE ROOM TYPE King size beds Queen size beds ROOM TOTALS 2 8 • Check in 14:00 – 16:00 PM, Check out 10:00 AM • We accept all major credit cards, except Diners • GPS co-ordinates: -25.7887 Latitude & 28.2502 Longitude • Average temperatures in Pretoria: MONTH JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC Min (°C) 17 17 16 12 8 5 4 7 12 14 15 17 Max (°C) 29 29 27 25 23 20 20 23 27 28 28 29 IN-ROOM FACILITIES: • Housekeeping once daily • Bathrobes • Air-conditioning • Complimentary essential • Tea & Coffee making facilities toiletries/amenities • Mini fridge • Electronic safe • Hairdryer • All Rooms have an en-suite • Television bathroom BOUTIQUE HOTEL FACILITIES: • Dining room or veranda • 24-hour security • Free Wi-Fi • Day Spa • Swimming Pool with minibar • Walking distance from Waterkloof • Scan & Fax Facilities Heights (Restaurants) • Secure Parking THINGS TO DO IN PRETORIA: • The Rovos Rail (9km) • Sun Arena Times Square (2km) • Menlyn Park (4km) • The Blue Train (7km) CONFERENCE STYLES: (Inclusive of a white board and a TV screen with an HDMI Cable) • Intimate conference room – between 8 and 12 delegates www.montdorpta.co.za 389 Eridanus Street, Waterkloof Ridge Pretoria, South Africa, 0181 Tel: +27 72 654 4122 TRANSPORT: Nearest Airport: OR Tambo International Airport (38km) - Airport transfers are available on arrangement. Closest Gautrain Station: Pretoria/Hatfield DIRECTIONS TO MONT D’OR BOHEMIAN HOUSE • 18 minutes from The Blue Train | 34 minutes from OR Tambo Airport | 39 minutes from Rovos Rail • TRAVEL BY AIR The closest airport to Bohemian House is Lanseria International Airport, which is 52,4 km away or OR Tambo Airport which is 46,7 km away. -

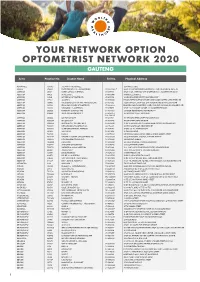

Your Network Option Optometrist Network 2020 Gauteng

YOUR NETWORK OPTION OPTOMETRIST NETWORK 2020 GAUTENG Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE AKASIA 478490 ENGELBRECHT A J A - WONDERPARK 012 5490086/7 SHOP 404 WONDERPARK SHOPPING C, CNR OF HEINRICH AVE & OL ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP U 142, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL, VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 141453 DU PLESSIS L C 011 8692488 99 MICHELLE AVENUE ALBERTON 145831 MEYERSDAL OPTOMETRISTS 011 8676158 10 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 177962 JANSEN N 011 9074385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR SWART KOPPIES & HEIDELBERG RD ALBERTON 192406 THEOLOGO R, DU TOIT M & PRINSLOO C M J 011 9076515 ALBERTON CITY, SHOP S03, CNR VOORTREKKER & DU PLESSIS ROAD ALBERTON 195502 ZELDA VAN COLLER OPTOMETRISTS 011 9002044 BRACKEN GARDEN SHOPPING CNTR, CNR DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR ALBERTON 266639 SIKOSANA J T - ALBERTON 011 9071870 SHOP 23-24 VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 280828 RAMOVHA & DOWLEY INC 011 9070956 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 348066 JANSE VAN RENSBURG C Y 011 8690754/ 25 PADSTOW STREET, RACEVIEW 072 7986170 ALBERTON 650366 MR IZAT SCHOLTZ 011 9001791 172 HENNIE ALBERTS STREET, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN P 011 9078745 1E FORE STREET, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7009259 BRACKEN CITY OPTOMETRISTS 011 8673920 SHOP 26 BRACKEN CITY, HENNIE ALBERTS ROAD, BRACKENHURST ALBERTON 7010834 NEW VISION OPTOMETRISTS CC 090 79235 19 NEW QUAY ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 7010893 I CARE OPTOMETRISTS ALBERTON 011 -

See the Sights, Hear the Sounds TSHWANE EXPERIENCE BUCKET LIST the CAPITAL EXPERIENCES DISCOVER THINGS to ESSENTIAL ADVENTURE TRAVEL INFO ACTIVITIES SEE & DO

A VISITORS’ GUIDE See the sights, hear the sounds TSHWANE EXPERIENCE BUCKET LIST THE CAPITAL EXPERIENCES DISCOVER THINGS TO ESSENTIAL ADVENTURE TRAVEL INFO ACTIVITIES SEE & DO discovertshwane.com @DISCOVERTSHWANE www.DiscoverTshwane.com - 4 - CONTENTS Experience Discover Jacaranda the Capital 6 our Gems16 City 20 Adventure Things To Bucketlist Activities18 See and Do30 Experiences38 -8- -9- -10- -12- -22- About City of Map of Essential Discover Tshwane Wonders Tshwane Travel Info Mamelodi -27- -46- -48- -52- -54- Tshwane Tshwane Taste of Travelling 10 Reasons Neighbourhoods on a Budget Tshwane in Tshwane to invest in Tshwane DISCOVER TSHWANE - 5 - FOREWORD GREETINGS FROM THE CAPITAL CITY! Welcome to our very first issue Immerse yourself in Tshwane’s of the Discover Tshwane visitors’ diverse tourism experiences and guide, the go-to magazine that then begin planning your next trip provides visitors with information on to our warm, vibrant and welcoming the City of Tshwane and its tourism city. offering. For more comprehensive Many people always ask what information about our destination, makes our city & region different, please access our website on: the answer to that question lies discovertshwane.com or get in touch in-between the covers of this with us through #discovertshwane magazine. on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter. It is full of great tips and ideas Enjoy your time in the City of that will help you maximize your Tshwane! experience of Tshwane when you get to visit. Through it, you will fall in love with our rich natural, cultural Immerse yourself and heritage resources, a number of in Tshwane’s beautiful buildings and attractions - “ from Church Square to the Palace of diverse tourism Justice, The Voortrekker Monument, experiences. -

Preferred Provider Pharmacies

PREFERRED PROVIDER PHARMACIES Practice no Practice name Address Town Province 6005411 Algoa Park Pharmacy Algoa Park Shopping Centre St Leonards Road Algoapark Eastern Cape 6076920 Dorans Pharmacy 48 Somerset Street Aliwal North Eastern Cape 346292 Medi-Rite Pharmacy - Amalinda Amalinda Shopping Centre Main Road Amalinda Eastern Cape Shop 1 Major Square Shopping 6003680 Beaconhurst Pharmacy Cnr Avalon & Major Square Road Beacon Bay Eastern Cape Complex 213462 Clicks Pharmacy - Beacon Bay Shop 26 Beacon Bay Retail Park Bonza Bay Road Beacon Bay Eastern Cape 192546 Clicks Pharmacy - Cleary Park Shop 4 Cleary Park Centre Standford Road Bethelsdorp Eastern Cape Cnr Stanford & Norman Middleton 245445 Medi-Rite Pharmacy - Bethelsdorp Cleary Park Shopping Centre Bethelsdorp Eastern Cape Road 95567 Klinicare Bluewater Bay Pharmacy Shop 6-7 N2 City Shopping Centre Hillcrest Drive Bluewater Bay Eastern Cape 6067379 Cambridge Pharmacy 18 Garcia Street Cambridge Eastern Cape 6082084 Klinicare Oval Pharmacy 17 Westbourne Road Central Eastern Cape 6078451 Marriott and Powell Pharmacy Prudential Building 40 Govan Mbeki Avenue Central Eastern Cape 379344 Provincial Westbourne Pharmacy 84C Westbourne Road Central Eastern Cape 6005977 Rink Street Pharmacy 4 Rink Street Central Eastern Cape 6005802 The Medicine Chest 77 Govan Mbeki Avenue Central Eastern Cape 376841 Klinicare Belmore Pharmacy 433 Cape Road Cotswold Eastern Cape 244732 P Ochse Pharmacy 17 Adderley Street Cradock Eastern Cape 6003567 Watersons Pharmacy Shop 4 Spar Complex Ja Calata Street -

Dis-Chem Clinics Offering Imupro, Ige and Lipidpro Sample Collections

Dis-Chem Clinics Offering ImuPro, IgE and LipidPro Sample Collections Please call ahead and ask to speak to the clinic sister to make a booking for your sample to be taken. Cape Town Shop E2 -E3 Bayside Mall, Cnr Blaauwberg Road & West Coast, Table View Cape Town Bayside Mall Western Cape South Africa 7441 021 522 6140 Shop F206 Blue Route Mall, 16 Tokai Road, Tokai Cape Town Blue Route Western Cape South Africa 7945 021 710 1230 Shop G41 Canal Walk Shopping Centre, Century Pl Boulevard Cape Town Canal Walk Western Cape South Africa 7441 021 551 5551 Shop G1 Standard Bank Galleria, 178-182 Main Road, Claremont Cape Town Claremont/Cavendish Western Cape South Africa 7700 021 673 1480 Shop 15 Sunvalley, Cnr Ou Kaapse Weg and Noordhoek Main Road Cape Town Noordhoek Western Cape South Africa 7975 021 784 4400 Paarl Mall Shop 95 Paarl Mall, Cnr Cecilla & New Vlei Road Paarl Western Cape South Africa 7620 021 863 5060 Shop 310 Somerset Mall, Cnr R44 & N2, Somerset West Cape Town Somerset Mall Western Cape South Africa 7130 021 850 5940 Shop 6 The Point Mall, 76 Regent Road, Sea Point The Point Cape Town Centre/Seapoint Western Cape South Africa 8005 021 430 2100 Pretoria Shop 206 Centurion Lake Mall, Heuwel Road Centurion Centurion Gauteng South Africa 0083 012 663-9363 Shop 35 Hillcrest Boulevard, Cnr Lynwood & Duxbury Road, Hatfield Pretoria Lynwood Gauteng South Africa 0083 012 362 3633 Shop U79 Kolonnade Shopping Centre, Cnr Dr van der Merwe & Sefako Makgatho Drive, Montana Montana Pretoria Gauteng South Africa 0182 012 523 9120 Shop 267 Woodlands Boulevard, Cnr Garsfontein Road & De Villabois Maruil Drive, Pretorius Park Ext. -

Wooltru Healthcare Fund Optical Network List Gauteng

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND OPTICAL NETWORK LIST GAUTENG PRACTICE TELEPHONE AREA PROVIDER NAME ADDRESS NUMBER NUMBER ACTONVILLE 195103 SUMAIYA ESSOP OPTOMETRIST 011 845 3644 688 ELLEMDEEN STREET ACTONVILLE 456640 ACTONVILLE OPTOMETRISTS 084 672 9235 1539 MAYET DRIVE ADDERLEY STREET 7009267 NURDEN & KIESER 011 8827000 150 JOHANNESBURG ROAD, HEERENGRACHT AKASIA 478490 TORGA OPTICAL WONDERPARK 012 549 0086/7 SHOP 404, WONDERPARK SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR BRITS ROAD & HEINRICH AVENUE AKASIA 748986 VISION WORKS WONDERPARK 012 549 4303 SHOP 530 WONDERPARK CENTRE, HEINRICH & OLD BRITS ROAD, KARENPARK AKASIA 766585 TORGA OPTICAL WONDERPARK 012 549 0086 SHOP 540 ENTRANCE 5, WONDERPARK CHARENE JANSE VAN RENSBURG LOW VISION ALBERANTE 348066 011 869 7106/7 1 DANIE THERON STREET SPECIALIST ALBERANTE 439584 E BOLT OPTOMETRIST 011 907 2034 1 DANIE THERON STREET ALBERTON 58017 TORGA OPTICAL ALBERTON 011 8691918 SHOP 69, ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING MALL ALBERTON 78484 AUDIENCE OPTOMETRIST 011 907 0956 SHOP 1A LIBERTAS BUILDING, 53 VOORTREKKER ROAD ALBERTON 177962 NARINDI JANSEN OPTOMETRIST 011 907 4385 LEMON TREE SHOPPING CENTRE, CNR. SWARTKOPPIES & HEIDELBERG ROAD ALBERTON 192406 SPEC SAVERS ALBERTON 011 907 6515 SHOP S0-3, LOWER LEVEL, ALBERTON CITY, VOORTREKKERSTRAAT STANLEY & DE KOCK OPTOMETRIST BRACKEN ALBERTON 195502 011 900 2044/83 CNR. DELPHINIUM & HENNIE ALBERTS STR, BRACKEN GARDENS SHOPPING CENTRE GARDENS ALBERTON 266639 EYEQUE OPTOMETRISTS 011 907 1870 SHOP23-24, VILLAGE SQUARE, 46 VOORTREKKER STREET ALBERTON 290416 M F CHABEDI OPTOMETRIST 011 867 7127 28 -

Store Locator

VISIT YOUR NEAREST EDGARS STORE TODAY! A CCOUNT Gauteng EDGARS BENONI LAKESIDE EDGARS WOODLANDS BLVD LAKESIDE MALL BENONI WOODLANDS BOULEVARD PRETORIUS PARK EDGARS BLACKHEATH CRESTA MAC MALL OF AFRICA CRESTA SHOPPING CENTRE CRESTA MALL OF AFRICA WATERFALL CITY EDGARS BROOKLYN EDGARS ALBERTON CITY BROOKLYN MALL AND DESIGN SQUARE NIEUW MUCKLENEUK ALBERTON CITY SHOPPING CENTRE ALBERTON EDGARS MALL AT CARNIVAL EDGARS SPRING MALL MALL AT CARNIVAL BRAKPAN SPRINGS MALL1 SPRINGS EDGARS CHRIS HANI CROSSING EDGARS CENTURION CENTRE CHRIS HANI CROSSING VOSLOORUS CENTURION MALL AND CENTURION BOULEVARD CENTURION EDGARS CLEARWATER MALL EDGARS CRADLE STONE MALL CLEARWATER MALL ROODEPOORT CRADLESTONE MALL KRUGERSDORP EDGARS EAST RAND EDGARS GREENSTONE MALL EAST RAND MALL BOKSBURG GREENSTONE SHOPPING CENTRE MODDERFONTEIN EDGARS EASTGATE EDGARS HEIDELBERG MALL EASTGATE SHOPPING CENTRE BEDFORDVIEW HEIDELBERG MALL HEIDELBERG EDGARS FESTIVAL MALL EDGARS JABULANI MALL FESTIVAL MALL KEMPTON PARK JABULANI MALL JABULANI EDGARS FOURWAYS EDGARS JUBILEE MALL FOURWAYS MALL FOURWAYS JUBILEE MALL HAMMANSKRAAL EDGARS KEYWEST EDGARS MALL OF AFRICA KEY WEST KRUGERSDORP MALL OF AFRICA WATERFALL EDGARS KOLONNADE EDGARS MALL OF THE SOUTH SHOP G 034 MALL OF THE SOUTH BRACKENHURST KOLONNADE SHOPPING CENTRE MONTANA PARK EDGARS MAMELODI CROSSING EDGARS MALL REDS MAMS MALL MAMELODI THE MALL AT REDS ROOIHUISKRAAL EXT 15 EDGARS RED SQUARE DAINFERN EDGARS MAPONYA DAINFERN SQUARE DAINFERN MAPONYA MALL KLIPSPRUIT EDGARS SOUTHGATE EDGARS MENLYN SOUTHGATE MALL SOUTHGATE MENLYN PARK SHOPPING -

479 4-11-2015 Gautengliquor

THE PROVINCE OF DIE PROVINSIE VAN UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG IN GAUTENG Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2.50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3.25 PRETORIA Vol. 21 No. 479 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1682-4525 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 00479 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 452005 2 No. 479 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, 4 NOVEMBER 2015 Government Printing Works No1-ice.submission dedLtn&s Government Printing Works has over the last few months implemented rules for completing and submitting the electronic Adobe Forms when you, the customer, submit your notice request. In line with these business rules, GPW has revised the notice submission deadlines for all gazettes. Please refer to the below table to familiarise yourself with the new deadlines. Government Gazette Type Publishing FrequencyPublication Date Submission Deadline Cancellations Deadline Tuesday, 12h00 - 3 days prior to National Gazette Weekly Friday Friday 15h00 for next Friday publication Friday 15h00, to be published Tuesday, 12h00 - 3 days prior to Regulation Gazette Weekly Friday the following Friday publication First Wednesday Petrol Price Gazette As required One week before publication 3 days prior to publication of the month Thursday 15h00, to be published Road Carrier Permits Weekly Friday 3 days prior to publication -

Edgars Active SHOP 3 RHINO PLAZA Eastern Cape Edgars Active 65

Edgars Active SHOP 3 RHINO PLAZA Eastern Cape Edgars Active 65 CATHCART RD Eastern Cape Edgars Active G52 METLIFE MALL Eastern Cape Edgars Active 1 DEVEREUX AVENUE Eastern Cape Edgars Active 91 HIGH STREEET Eastern Cape Edgars Active SHOP 6 SHOPRITE CENTRE Eastern Cape Edgars Active SHOP 110 GREENACRES MALL Eastern Cape (PE) Edgars Active Cnr Voortrekker & Du Plessis Free State Edgars Active SHOP 33 Free State Edgars Active SHOP 9 DIEPSLOOT MALL CNR WILLIAM Gauteng NICOL &PLUM STREET Edgars Active SHOP 3 Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 14 VINEYARD MALL Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 13 ATLYN MALL Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 2 Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 21 Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 33 Gauteng Edgars Active Shop 128, Menlyn Hyperama, Atterbury Gauteng Road, Menlyn Park, Edgars Active EDGARS ACTIVE COSMOCITY MALL Gauteng Edgars Active CLEARWATER MALL Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 12 MAYFIELD SQUARE Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 38 DAVEYTON MALL Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 2A ALKIALM BUILDING Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 40 DOBSONVILLE SHOPPING Gauteng CENTRE Edgars Active SHOP 3 GOLDENWALK MALL VICTORIA Gauteng STREET Edgars Active SHOP75 - 77 Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 14 SONTONGA MALL Gauteng Edgars Active THABONG SHOPPING CENTRE, UNIT 10, Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP 23 EDENDALE MALL Gauteng Edgars Active SHOP B SHOPRITE CENTRE KwaZulu-Natal Edgars Active 104 CHURCH STREET KwaZulu-Natal Edgars Active SHOP 50 MARUIS KRUGER STREET KwaZulu-Natal Edgars Active 321 MAIN ROAD KwaZulu-Natal Edgars Active SHOP 18 KwaZulu-Natal Edgars Active SHOP 21 MTUBA TAXI CITY -

Download Issue 10

Y R T N U O C B U A CL PRETORI PRETORIA COUNTRY CLUB PRETORIA COUNTRY TENNIS SECTION 04 Message from the Chairman CLUB 32 Tennis coaching 06 From the General Manager 22 110 years’ memories 24 Families first INTERVIEW GOLF SECTION 34 George Coetzee SQUASH SECTION 10 Men’s Golf 26 “Best Squash Club” PARTNERSHIP 15 Ladies Golf second year running PROGRAMME 36 Discount offers SNOOKER SECTION WINE FRATERNITY 18 Don’t sink the white 28 Wine evenings at PCC CORPORATE MEMBERS PRETORIA CLUB BOWLS SECTION 41 Twenty and counting... 20 Conviviality and good cheer 30 Did you know...? RECIPROCITY 46 Our international friends IMPORTANT CONTACT DETAILS RECEPTION OPERATING HOURS N9NE CATERING 012 460 6241/2/3/4 012 346 1707 Monday: 07h00 – 18h00 [email protected] Tuesday to Saturday: 07h00 – 19h00 Sunday: 08h00 – 17h00 BLU SAFFRON 012 346 0223/4 OFFICE OPERATING HOURS [email protected] 012 460 6241/2/3/4 Monday to Thursday: 08h00 – 16h30 You can contact any of the management team Friday: 08h00 – 16h00 or make an appointment with them. They are situated in the main Clubhouse on the premises. PRO SHOP/ GOLF DIRECTORS 012 460 3372 [email protected] PRIVACY POLICY [email protected] Pretoria Country Club is sensitive about the confidentiality of our members’ information and GOLF MANAGER we assure you that your details will not be made [email protected] available to any third parties whatsoever. value and participation, as soon as practically Everything we do and plan to do is to ensure that, possible.