A Poetics of Interruption: Fugitive Speech Acts and the Politics of Noise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Urban Chora, from Pre-Ancient Athens to Postmodern Paris

China Media Research, 13(4), 2017 http://www.chinamediaresearch.net The Urban Chora, from Pre-Ancient Athens to Postmodern Paris Janell Watson Virginia Tech, USA Abstract: Jacques Derrida and Michel Serres challenge the binary logic of Western philosophy very differently, Derrida through a philosophy of discourse, Serres through a philosophy of things. Serres has begun to draw more international readers thanks to a recent shift in critical emphasis from words to things. The difference between deconstruction’s word-orientated acosmism and the newer versions of thing-oriented cosmism can be fruitfully explored by comparing Derrida to Serres on the basis of their readings of Plato’s cosmogony, focused on the figure of chora in Timaeus. [Janell Watson. The Urban Chora, from Pre-Ancient Athens to Postmodern Paris. China Media Research 2017; 13(4): 28-37]. 4 Keywords: Jacques Derrida, Michel Serres, Peter Eisenman, Plato, chora Jacques Derrida and Michel Serres share the critical concern about human-nonhuman relations ambition of overcoming the dualist, binary logic of non- manifests itself in ecocriticism, new materialism, contradiction which, they complain, has dominated animal studies, posthumanism, anthropocene studies, Western philosophy since Plato. However, they object-oriented continental philosophy, the challenge non-contradiction very differently, Derrida architecture of the fold, actor-network theory, and the through a philosophy of discourse, Serres through a concept of vibrant matter. Once again, matter matters. philosophy of things. These two thinkers, both born in As Serres puts it in his recently translated Geometry, 1930, overlapped at the École normale supérieure in the cosmos has returned as “philosophy’s paradigm, Paris, and thus come from the same intellectual time and its real model,” as in the time of the ancients, but with place. -

Fall 2013 UG Course Descriptions.Docx

UNDERGRADUATE SPRING 2019 COURSE DESCRIPTIONS PHI 100 (B, HUM) Concepts of the Person, Main Focus An historical introduction to philosophy through readings and discussions on topics such as human identity, human understanding, and human values. PHI 100.01 MWF 12:00-12:53 A. Bernstein In this class, we will ask the question, “What does it mean to be a person?” We will explore the question by making our way through challenging and fascinating texts, whether they are classically considered “philosophy” or not. The question of personhood is always broadly philosophical, but we will investigate whether that which is institutionally called “philosophy” is up to the task of answering the question. We will explore these things through the lenses of media, technology, culture, psychology, literature, and more. Through these interventions, we will try to get a handle on to what extent the concept of personal identity is even still sustainable in our postmodern, “post-truth” society. This class interrogates concepts of the person. PHI 100.02 MWF 10:00-10:53 J. Sares What is Thinking?: The Human Between Animal and Machine The course examines what it means to be a human being in terms of the capacity for conceptual thought and subjectivity. In part one, we will compare the human being to nonhuman animals, questioning whether there is a continuity or radical break between human and nature. Topics in this section may include: Aristotle’s definition of the human being as a ‘rational animal,’ Descartes’ substance dualism, Hobbes’ materialism, the philosophies of nature of Schelling and Hegel, and psychoanalytic accounts of the human being. -

Attached: the Object and the Collective

Bernhard Siegert Attached: The Object and the Collective 1 Cultural Techniques in 1983, 2000, 2020 As one of the reports written in the course of Friedrich Kittler’s Habilitation pro- cedure attests, in 1983 in the context of the humanities, the term “cultural tech- niques” carried the stigma of being unscientific. Kittler’s Aufschreibesysteme 1800/1900 (1985, translated as Discourse Networks 1800/1900) was regarded as belonging to a type of book that might be labeled “kulturtechnisch,” which included other works such as Hans-Dieter Bahr’s Über den Umgang mit Maschinen (1983, “On interacting with machines”), Jean Baudrillard’s L’Échange symbolique et la mort (1976, Symbolic Exchange and Death), Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge’s Geschichte und Eigensinn (1981, History and Obstinacy), Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s Geschichte der künstlichen Helligkeit im 19. Jahrhundert (1983, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century), or Jacques Derrida’s La carte postale (1980, The Post Card). What these books have in common (if nothing else) is that they appear to suspend “the proven foundations of scientific knowl- edge.”1 Kittler himself had made use of the term “cultural techniques” at the end of the summer of 1983 in the preface he was pressured to write (which was later suppressed) for Aufschreibesysteme 1800/1900. “Even écriture, which has in the meantime become a hermeneutic slogan, does not use the term ‘cultural tech- niques’ to mean cultural techniques.”2 Describing reading and writing as cultural techniques meant, -

ON HYPERSTTION in THEORY Armen Avanessian

REINVENTING HORIZONS nize the imbalanced nature of their relationship, so grows their ACCELERATING ACADEMIA: demand for equality and their technical capacity to be in charge of their destiny. This realization opens up a space for intervening ON HYPERSTTION in history and for creating new horizons of possibility.22 IN THEORY Armen Avanessian Recall that hype is the ratio of expected earnings to earnings (EE/E), whereas the above impressions are based on the ratio of capitalization to earnings (K/E). The latter number refects both hype and the discount rate (K/E = H/r), so un- less we know what capitalists expect, we remain unable to say anything specifc about hype. But we can speculate[…] —Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan1 The new realist and materialist philosophy and the new po- litical theory which it explicitly inspired, assert that reality can be known and that change is possible. Rather than spell out here what this entails in the various currents of thought that range from New Materialism via Speculative Realism to 22. A diferent version of this essay was originally presented as part of Ashkal Alwan’s Home 1. Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder, Works 7, a Forum on Cultural Practices in Beirut on November 18, 2015. (Milton Park: Routledge, 2009), 190. 76 77 REINVENTING HORIZONS AVANESSIAN—ACCELERATING ACADEMIA Accelerationism, I would like to look at the discursive framework logical. This common folkloristic mystifcation of the past is best and background information that have led to their engagement countered with an accelerationist perspective on the origins of with the scientifc and (fnancial-) economic phenomena that the modern research university. -

Primal Scream Juntam-Se Ao Cartaz Do Nos Alive'19

COMUNICADO DE IMPRENSA 02 / 04 / 2019 NOS apresenta dia 12 de julho PRIMAL SCREAM JUNTAM-SE AO CARTAZ DO NOS ALIVE'19 Os escoceses Primal Scream são a mais recente confirmação do NOS Alive’19. A banda liderada por Bobby Gillespie, figura incontornável da música alternativa, sobe ao Palco NOS dia 12 de julho juntando-se assim aos já anunciados Vampire Weekend, Gossip e Izal no segundo dia do festival. Com mais de 30 anos de carreira, Primal Scream trazem até ao Passeio Marítimo de Algés o novo álbum com data de lançamento previsto a 24 de maio, “Maximum Rock N Roll: The Singles”, trabalho que reúne os singles da banda desde 1986 até 2016 em dois volumes. A compilação começa com “Velocity Girl”, passando por temas dos dois primeiros álbuns como são exemplo "Ivy Ivy Ivy" e "Loaded". A banda que tinha apresentado em outubro de 2018 a mais recente compilação de singles originais do quarto álbum de 1994 com “Give Out But Don’t Give Up: The Original Memphis Recordings”, juntando-se ao lendário produtor Tom Dowd, a David Hood (baixo) e Roger Hawkins (bateria) no Ardent Studios em Memphis, está de volta às gravações e revelam algo nunca antes ouvido e uma banda que continua a surpreender. Primal Scream foi uma parte fundamental da cena indie pop dos anos 80, depois do galardoado disco "Screamadelica" vencedor do Mercury Prize em 1991, considerado um dos maiores de todos os tempos, a banda seguiu por influências de garage rock e dance music até ao último trabalho discográfico “Chaosmosis” lançado em 2016. -

Wiseman-Trowse20134950

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Book Section Title: The singer and the song: Nick Cave and the archetypal function of the cover version Creators: Wiseman-Trowse, N. J. B. R Example citation: Wiseman-Trowse, N. J. B. (2013) The singer and the song: Nick Cave and the archetypal function oAf the cover version. In: Baker, J. (ed.) The Art of Nick Cave: New Critical Essays. Bristol: Intellect. pp. 57-84. T Version: Final draft C NhttEp://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/4950/ The singer and the song: Nick Cave and the archetypal function of the cover version Nathan Wiseman-Trowse The University of Northampton A small proscenium arch of red light bulbs framing draped crimson curtains fills the screen. It is hard to tell whether the ramshackle stage is inside or outside but it appears to be set up against a wall made of corrugated metal. All else is black. The camera cuts to a close-up of the curtains, which are parted to reveal a pale young man with crow’s nest hair wearing a sequined tuxedo and a skewed bow tie. The man holds a lit cigarette and behind him, overseeing proceedings, is a large statue of the Virgin Mary. As the man with the crow’s nest hair walks fully through the arch he opens his mouth and sings the words ‘As the snow flies, on a cold and grey Chicago morn another little baby child is born…’. The song continues with the singer alternately shuffling as if embarrassed by the attention of the camera and then holding his arms aloft in declamation or fixing the viewer with a steely gaze. -

Papers of Surrealism, Issue 8, Spring 2010 1

© Lizzie Thynne, 2010 Indirect Action: Politics and the Subversion of Identity in Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s Resistance to the Occupation of Jersey Lizzie Thynne Abstract This article explores how Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore translated the strategies of their artistic practice and pre-war involvement with the Surrealists and revolutionary politics into an ingenious counter-propaganda campaign against the German Occupation. Unlike some of their contemporaries such as Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon who embraced Communist orthodoxy, the women refused to relinquish the radical relativism of their approach to gender, meaning and identity in resisting totalitarianism. Their campaign built on Cahun’s theorization of the concept of ‘indirect action’ in her 1934 essay, Place your Bets (Les paris sont ouvert), which defended surrealism in opposition to both the instrumentalization of art and myths of transcendence. An examination of Cahun’s post-war letters and the extant leaflets the women distributed in Jersey reveal how they appropriated and inverted Nazi discourse to promote defeatism through carnivalesque montage, black humour and the ludic voice of their adopted persona, the ‘Soldier without a Name.’ It is far from my intention to reproach those who left France at the time of the Occupation. But one must point out that Surrealism was entirely absent from the preoccupations of those who remained because it was no help whatsoever on an emotional or practical level in their struggles against the Nazis.1 Former dadaist and surrealist and close collaborator of André Breton, Tristan Tzara thus dismisses the idea that surrealism had any value in opposing Nazi domination. -

Demonstration and Interpretation

Serres, M. Demonstration and Interpretation pp. 77-123 Michel Serres with Bruno Latour. Transl. by Roxanne Lapidus, (1996) Conversations on science, culture, and time Univ. of Michigan Press Staff and students of University of Warwick are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: • access and download a copy; • print out a copy; Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material and should not download and/or print out a copy. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by University of Warwick. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

Thinking With, Through and for Nature – Michel Serres, Branches (2020). London: Bloomsbury

Johnson, P. (2020). Thinking With, Through and For Nature – Michel Serres, Branches (2020). London: Bloomsbury. Anthropocenes – Human, Inhuman, Posthuman, 1(1): 15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16997/ahip.34 REVIEW Thinking With, Through and For Nature – Michel Serres, Branches (2020). London: Bloomsbury Peter Johnson Branches is Michel Serres’ latest book to be translated into English. The title is a pertinent description of his overall philosophical thought and practice which spread in multiple directions, working from different but overlapping stems, involving the human, the inhuman and the nonhuman. Serres became a bestselling author in France but has been largely neglected in Anglophone scholarship. Branches is a good a place as any to start to navigate and provide a glimpse of his lucidly inclusive and complex thought. Keywords: Michel Serres; ecology; climate crisis; Anthropocene; trandisciplinarity Michel Serres is an uncomfortable philosopher with Serres’ stochastic practice likewise strays, meanders, an uncomfortable philosophy. Although he wrote over opens, sets adrift, matching how things of the world, living sixty transdisciplinary books from the 1960s to the year and inert, move, divert, flourish and deteriorate. He finds of his death in 2019, many of which concern political evidence for this in the ancient philosophy of Lucretius ecology and the Anthropocene from a decentred human which he audaciously claims anticipates, or in fact is perspective, he has been largely ignored in Anglophone isomorphic with, advanced sciences such as chaos theory, scholarship. Why has he been neglected? His thought is an idea explicitly acknowledged by Prigogine and Stengers utterly impossible to pigeon-hole; he mixes styles, points in their ground-breaking Order out of Chaos (2018). -

Covert Plants

COVERT PLANTS Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contributions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our adventure is not possible without your support. Vive la open-access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) Covert Plants Vegetal Consciousness and Agency in an Anthropocentric World Edited by Prudence Gibson & Baylee Brits Brainstorm Books Santa Barbara, California covert plants: Vegetal Consciousness and Agency in an anthropocentric world. Copyright © 2018 by the editors and authors. This work carries a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform, and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors and editors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2018 by Brainstorm Books A division of punctum books, Earth, Milky Way www.punctumbooks.com isbn-13: 978-1-947447-69-1 (print) isbn-13: 978-1-947447-70-7 (epdf) lccn: 2018948912 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Interior design: Vincent W.J. -

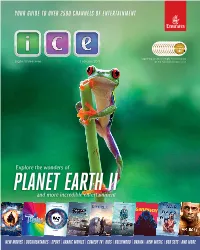

Your Guide to Over 2500 Channels of Entertainment

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment Digital Widescreen February 2017 for the 12th consecutive year! PLANET Explore the wonders ofEARTH II and more incredible entertainment NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE ENTERTAINMENT An extraordinary experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. 496 movies Information… Communication… Entertainment… THE LATEST MOVIES Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 STAY CONNECTED ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS Connect to the OnAir Wi-Fi 4 103 network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s Move around 1 Choose a channel using the games Go straight to your chosen controller pad programme by typing the on your handset channel number into your and select using 2 3 handset, or use the onscreen the green game channel entry pad button 4 1 3 Swipe left and right like Search for movies, a tablet. Tap the arrows TV shows, music and ĒĬĩĦĦĭ onscreen to scroll system features ÊÉÏ 2 4 Create and access Tap Settings to Português, Español, Deutsch, 日本語, Français, ̷͚͑͘͘͏͐, Polski, 中文, your own playlist adjust volume and using Favourites brightness Many movies are available in up to eight languages.