The Battle for Yarrow Stadium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oakura July 2003

he akura essenger This month JULY 2003 Coastal Schools’ Education Development Group Pictures on page 13 The Minister of Education, Trevor Mallard, has signalled a review of schooling, to include Pungarehu, Warea, Newell, Okato Primary, Okato College, Oakura and Omata schools. The reference group of representatives from the area has been selected to oversee the process and represent the community’s perspective. Each school has 2 representatives and a Principal rep from the Primary and Secondary sector. Other representatives include, iwi, early childhood education, NZEI, PPTA, local politicians, Federated Farmers, School’s Trustee Association and the Ministry of Education in the form of a project manager. In general the objectives of the reference group are to be a forum for discussion of is- sues with the project manager. There will be plenty of opportunity for the local com- Card from the Queen for munities to have input. Sam and Tess Dobbin Page 22 The timeframe is to have an initial suggestion from the Project Manager by September 2003. Consultation will follow until December with a preliminary announcement from the Ministry of Education in January 2004. Further consultation will follow with the Minister’s final announcement likely in June 2004. This will allow for any develop- ment needed to be carried out by the start of the 2005 school year. The positive outcome from a review is that we continue to offer quality education for Which way is up? the children of our communities for the next 10 to 15 years as the demographics of our communities are changing. Nick Barrett, Omata B.O.T Chairperson Page 5 Our very own Pukekura Local artist “Pacifica of Land on Sea” Park? Page 11 exhibits in Florence Local artist Caz Novak has been invited to exhibit at the Interna- tional Biennale of Contemporary Art in Florence this year. -

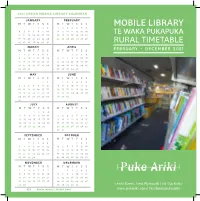

Mobile Library

2021 URBAN MOBILE LIBRARY CALENDAR JANUARY FEBRUARY M T W T F S S M T W T F S S MOBILE LIBRARY 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 TE WAKA PUKAPUKA 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 RURAL TIMETABLE MARCH APRIL M T W T F S S M T W T F S S FEBRUARY - DECEMBER 2021 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 MAY JUNE M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 31 JULY AUGUST M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 1 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 SEPTEMBER OCTOBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 NOVEMBER DECEMBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 1 Ariki Street, New Plymouth | 06-759 6060 KEY RURAL MOBILE LIBRARY DAYS www.pukariki.com | facebook/pukeariki Tuesday Feb 9, 23 Mar 9, 23 April 6 May 4, 18 TE WAKA PUKAPUKA June 1, 15, 29 July 27 Aug 10, 24 Sept 7, 21 Oct 19 Nov 2, 16, 30 Dec 14 Waitoriki School 9:30am – 10:15am Norfolk School 10:30am – 11:30am FEBRUARY - DECEMBER 2021 Ratapiko School 11:45am – 12:30pm Kaimata School 1:30pm – 2:30pm The Mobile Library/Te Waka Pukapuka stops at a street near you every second week. -

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Man Loose Forwards

ROD McKENZIE JACK FINLAY BRIAN FINLAY KEVIN EVELEIGH MANAWATU: MANAWATU: MANAWATU: MANAWATU: 1933-1939 (41 games) 1934-1946 (61 games) 1950-1960 (92 games) 1969-1978 Regarded as Finlay played for Finlay went from being (107 games) Manawatu’s finest Manawatu in positions the hunted to the hunter. Few players in New player pre-World War II. Capable of as diverse as prop and first After nearly nine seasons as a midfield Zealand rugby could match playing lock or loose forward, five-eighth. He makes the cut in this back, he was transformed into a flanker Eveleigh’s wholehearted approach. McKenzie got the full respect of selection at No 8, the position that for a Ranfurly Shield challenge against He was the scourge of opposition his team-mates with his took him into the All Black in 1946. Taranaki in New Plymouth in 1958. He backs as he launched himself off the commitment on the field. Finlay was great at keeping made life miserable for the Taranaki side of scrums and mercilessly McKenzie became an All Black passing movements going, and inside backs with his speed and chased them down. Hayburner’s in 1934, going on to play 34 was vice-captain of the “Kiwis” anticipation. His form on the flank for fitness regimen was legendary. He times. In 1938 he became Army team. When returning from Manawatu led to selection for the first was an All Black between 1974 and the only Manawatu player military service to play for 1959 test against the British Lions. 1977 and captained Manawatu to a to captain the All Blacks Manawatu in 1946,Finlay’s Injury curtailed his involvement in the 20-10 win over Australia in 1978. -

Draft Taranaki Regional Public Transport Plan 2020-2030

Draft Regional Public Transport Plan for Taranaki 2020/2030 Taranaki Regional Council Private Bag 713 Stratford Document No: 2470199 July 2020 Foreword (to be inserted) Table of contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Strategic context 2 2.1. Period of the Plan 4 3. Our current public transport system 5 4. Strategic case 8 5. Benefits of addressing the problems 11 6. Objectives, policies and actions 12 6.1. Network 12 6.2. Services 13 6.3. Service quality 14 6.4. Farebox recovery 17 6.5. Fares and ticketing 17 6.6. Process for establishing units 19 6.7. Procurement approach for units 20 6.8. Managing, monitoring and evaluating unit performance 22 6.9. Transport-disadvantaged 23 6.10. Accessibility 24 6.11. Infrastructure 25 6.12. Customer interface 26 7. Proposed strategic responses 28 Appendix A: Public transport services integral to the public transport network 31 Appendix B: Unit establishment 34 Appendix C: Farebox recovery policy 36 Appendix D: Significance policy 40 Appendix E: Land Transport Management Act 2003 requirements 42 1. Introduction The Taranaki Regional Public Transport Plan (RPTP or the plan), prepared by Taranaki Regional Council (the Council), is a strategic document that sets out the objectives and policies for public transport in the region, and contains details of the public transport network and development plans for the next 10 years (2020-2030). Purpose This plan provides a means for the Council, public transport operators and other key stakeholders to work together in developing public transport services and infrastructure. It is an instrument for engaging with Taranaki residents on the design and operation of the public transport network. -

Economic and Commercial Impact of 2011 Rugby World

EMBARGOED UNTIL 4PM (NZST), SEPTEMBER 13, 2011 ECONOMIC IMPACT REPORT ON GLOBAL RUGBY PART IV: RUGBY WORLD CUP 2011 Commissioned by MasterCard Worldwide Researched and prepared by the Centre for the International Business of Sport Coventry University Dr Simon Chadwick Professor of Sport Business Strategy and Marketing Dr. Anna Semens Research Fellow Dr. Dave Arthur CIBS Researcher Senior Lecturer in Sport Business Southern Cross University, Australia September 13, 2011 Economic Impact Report on Global Rugby Part IV: Rugby World Cup 2011 EMBARGOED UNTIL 4PM NZST ON 13 SEPTEMBER 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On Sunday, October 23rd the Rugby World Cup 2011 Final will take place at Eden Park, New Zealand and become the only venue to stage the event twice in the 24-year history of the Tournament. The six-week, 48-match Tournament promises to be a total Rugby experience for everybody involved, from the estimated cumulative global television audience of 4 billion to the 95,000 international visitors expected to attend and from the 20 competing nations to the range of sponsors and official suppliers. Given the scale and level of investment in the event and in challenging economic conditions, much interest has focused on the scale of the economic impact on both the local New Zealand economy and also the broader global sports economy. Rugby World Cup has grown markedly since its first iteration with a cumulative television audience of 300 million in 1987 growing to 4.2 billion1 for Rugby World 2007 and spectators increasing from 600,000 to 2.25 million. Participating countries has risen from 16 in 1987 to 94 in 2007 with the number of countries in which the Tournament is broadcast up from 17 to 202. -

MA10: Museums – Who Needs Them? Articulating Our Relevance and Value in Changing and Challenging Times

MA10: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? Articulating our relevance and value in changing and challenging times HOST ORGANISATIONS MAJOR SPONSORS MA10: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? Articulating our relevance and value in changing and challenging times WEDNESDAY 14 – FRIDAY 16 APRIL, 2010 HOSTED BY PUKE ARIKI AND GOVETt-BREWSTER ART GALLERY VENUE: TSB SHOWPLACE, NEW PLYMOUTH THEME: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? MA10 will focus on four broad themes that will be addressed by leading international and national keynote speakers, workshops and case studies: Social impact and creative capital: what is the social relevance and contribution of museums and galleries within a broader framework? Community engagement: how do we undertake audience development, motivate stakeholders as advocates, and activate funders? Economic impact and cultural tourism: how do we demonstrate our economic value and contribution, and how do we develop economic collaborations? Current climate: how do we meet these challenges in the current economic climate, the changing political landscape nationally and locally, and mediate changing public and visitor expectations? INTERNATIONAL SPEAKERS INCLUDE MUSEUMS AOTEAROA Tony Ellwood Director, Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art Museums Aotearoa is New Zealand’s Elaine Heumann Gurian Museum Advisor and Consultant independent professional peak body for museums and those who work Michael Houlihan Director General, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales in or have an interest in museums. Chief Executive designate, Te Papa Members include museums, public art galleries, historical societies, Michael Huxley Manager of Finance, Museums & Galleries NSW science centres, people who work within these institutions and NATIONAL SPEAKERS INCLUDE individuals connected or associated Barbara McKerrow Chief Executive Officer, New Plymouth District Council with arts, culture and heritage in New Zealand. -

TSB COMMUNITY TRUST REPORT 2016 SPREAD FINAL.Indd

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CHAIR’S REPORT Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa Greetings, greetings, greetings to you all The past 12 months have been highly ac ve for the Trust, As part of the Trust’s evolu on, on 1 April 2015, a new Group marked by signifi cant strategic developments, opera onal asset structure was introduced, to sustain and grow the improvements, and the strengthening of our asset base. Trust’s assets for future genera ons. This provides the Trust All laying stronger founda ons to support the success of with a diversifi ca on of assets, and in future years, access to Taranaki, now and in the future. greater dividends. This year the Trust adopted a new Strategic Overview, As well as all this strategic ac vity this year we have including a new Vision: con nued our community funding and investment, and To be a champion of posi ve opportuni es and an agent of have made a strong commitment to the success of Taranaki benefi cial change for Taranaki and its people now and in communi es, with $8,672,374 paid out towards a broad the future range of ac vi es, with a further $2,640,143 commi ed and yet to be paid. Our new Vision will guide the Trust as we ac vely work with others to champion posi ve opportuni es and benefi cial Since 1988 the Trust has contributed over $107.9 million change in the region. Moving forward the Trust’s strategic dollars, a level of funding possible due to the con nued priority will be Child and Youth Wellbeing, with a focus on success of the TSB Bank Ltd. -

Escribe Agenda Package

Council Briefing Agenda Date: Tuesday, 26 November, 2019 Time: 9:00 am Location: Council Chamber Forum North, Rust Avenue Whangarei Elected Members: Her Worship the Mayor Sheryl Mai (Chairperson) Cr Gavin Benney Cr Vince Cocurullo Cr Nicholas Connop Cr Ken Couper Cr Tricia Cutforth Cr Shelley Deeming Cr Jayne Golightly Cr Phil Halse Cr Greg Innes Cr Greg Martin Cr Anna Murphy Cr Carol Peters Cr Simon Reid For any queries regarding this meeting please contact the Whangarei District Council on (09) 430-4200. Pages 1. Apologies 2. Reports 2.1 2020 - 2021 Annual Plan and the Corporate Planning Cycle 1 2.2 Governance of the Northland Events Centre 3 3. Closure of Meeting 1 2.1 2020 – 2021 Annual Plan and the Corporate Planning Cycle Meeting: Council Briefing Date of meeting: 26 November 2019 Reporting officer: Dominic Kula (General Manager – Strategy and Democracy) 1 Purpose The purpose of the briefing is to provide Elected Members with an overview of the 2020 – 2021 Annual Plan process. 2 Background The corporate planning cycle revolves around the Long Term Plan (adopted every three years), the Annual Plan (adopted every year, except the year the Long Term Plan is adopted) and the Annual Report (adopted every year). The 2018-2028 Long Term Plan (LTP) was adopted on the 28 June 2018. It establishes the budget baseline for the 2020-2021 financial year. As such, the starting point for the Annual Plan process is a review of Year 3 of the LTP considering: New information impacting the budget; Council resolutions that impact the budget; and Timing variances of LTP projects that impact the Plan budget/work programme 3 Discussion The Annual Plan for the 2020-2021 year (1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021) will be the last one before the new LTP. -

6110B10ee091a31e4bc115b0

ARENASARENAS In December 2016 HG Sports Turf installed its Eclipse Stabilised Turf system at Westpac Stadium in Wellington. The new surface had its first outing on New Year’s Day with an A-League clash between the Wellington Phoenix and Adelaide United IcingIcing onon thethe CakeCake TinTin PHOTOS COURTESY OF HG SPORTS TURF AND WESTPAC STADIUM TURF AND WESTPAC OF HG SPORTS PHOTOS COURTESY Affectionately dubbed the estpac Stadium, or Wellington Regional adequate to cater for international events due to its In addition to sporting events, Westpac Stadium stabilisation or reinforcement. This combined with Stadium, is a major sporting venue in age and location. A new stadium was also needed regularly hosts major events and concerts. Shortly an ever-increasing events strategy, and the need for ‘Cake Tin’ by the locals, W Wellington, New Zealand which was to provide a larger-capacity venue for One Day after opening in 2000, it hosted the Edinburgh the stadium to be a multi-functional events space for officially opened in early 2000. Residing one International cricket matches, due to the city’s Basin Military Tattoo, the first time the event was held sports and non-sports events, meant it needed a turf Westpac Stadium in New kilometre north of the Wellington CBD on reclaimed Reserve ground losing such matches to larger outside of Edinburgh, Scotland, while in 2006 it system that would be up to the challenge. railway land, it was constructed to replace Athletic stadia in other parts of the country. hosted WWE’s first ever New Zealand show in front HG Sports Turf (HGST), which had previously Zealand’s capital Wellington Park, the city’s long-standing rugby union venue. -

Contents Submission No: 3101 Alan Crawford

Contents Submission No: 3101 Alan Crawford ............................................................................................. 4038 Submission No: 3102 Ainslee Taikoko ........................................................................................... 4040 Submission No: 3103 Suzy Carswell ............................................................................................... 4041 Submission No: 3104 Derik ............................................................................................................ 4042 Submission No: 3105 Catherine Cheung ....................................................................................... 4043 Submission No: 3106 Kirsty Jane McMurray ................................................................................. 4045 Submission No: 3107 Anne Scott ................................................................................................... 4046 Submission No: 3108 Mary Southee .............................................................................................. 4047 Submission No: 3109 Aileen Ruddick............................................................................................. 4048 Submission No: 3110 Brendon Cook.............................................................................................. 4049 Submission No: 3111 Sandy Campbell ........................................................................................... 4050 Submission No: 3112 Cohin Thomason ........................................................................................ -

The Realised Economic Impact of the 2011 Rugby World Cup – a Host City Analysis

THE REALISED ECONOMIC IMPACT OF THE 2011 RUGBY WORLD CUP – A HOST CITY ANALYSIS Sam Richardson1 School of Economics and Finance College of Business Massey University Palmerston North New Zealand Brown Bag Seminar, December 2012 (Work in Progress) Abstract The 2011 Rugby World Cup, hosted by New Zealand, was projected to make an operational loss of NZ$39.3 million, of which taxpayers were to foot two‐thirds of the bill. This was in contrast to profits of A$48 million for the 2003 tournament in Australia and €30 million for the 2007 tournament in France. Part of the justification for incurring these losses was an expectation of significant economic benefits arising from the hosting of the tournament. This paper estimates the realised economic impact on host cities during the 2011 tournament. Estimates show that the aggregated realised impact was approximately 25% of pre‐event projections and the impacts were unevenly distributed across host cities. 1 E‐Mail: [email protected]; Telephone: +64 6 3569099 ext. 4583; Fax: +64 6 350 5660. 1 1. INTRODUCTION The 2011 Rugby World Cup (RWC) was hosted in New Zealand, and is the largest sporting event held in this country to date. One of the selling points of the successful bid for the tournament in 2005 was that the country was described as a “stadium of four million”, which subsequently became the catchphrase synonymous with the event. In all, 48 matches were played in 12 cities during September and October 2011, while other cities also acted as bases for the 20 competing teams throughout their stay.