Bronx, Blacks, and the NFL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Senator Lehman As Fifth, Distinguished Lectu Will Deliver

:iVn-1,,TSW«a^ .-•tfinrf.V. .,+,. •"- • , --v Show ' • • V '•<•'' •• — * Page 3 '•"•:• ^U- Baruch School of Business and Public Administration City College of New York Vol: XXXVri!—No. 8 Tuesday. March 19. 1957 389 By Subscription -Only Former Senator Lehman Beginning Friday, the cafe- [tgria will be clooed at 3 evei> Friday- for the remainder of As Fifth, Distinguished Lectu [the term. Prior to this ruling, the cafeteria was closed &t 4:30. [The Cafeteria Committee, Will Deliver Address April 2 in [headed by Ed-ward Mamraen of By Gary J. Strum . -i| the Speech Department, made O the change due to lack of busi Herbert H. Lehman, former Governor and Senator f rom New York State, will be the fifth speaker in the Bernard ness after 3. There is no eve- M. Baruch Distinguished Lecturer series. " * " I ning session service Fridays. Lehman's talk will take place Tuesday, April 2, at 10:15 in Pauline Edwards Theatre. .•...•---. " ; / City College Buell G. Gallagher will officiate at the occasion and classes will be suspended to enable students to'afc- : tend the function. Prior to his election to the United States Senate in 1949, axe Divulges Plan Lehman worked as Director Gen-, eral of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administra tion. or New Cafeteria Lehman was born in New York Dean Emanuel Saxe announced Thursday night that a City March 28, 1878, and he re afeteria will be installed on the eleventh floor. ceived a BA degree from Wil The new dining area plan was part of a space survey liams College. -

Make a Good Deal

10938_Bergs_01.c.qxd 12/1/03 4:01 PM Page 1 CHAPTER 1 Make a Good Deal Finding the right location and lining up good lenders are some of the easier aspects to buying real estate. What’s tricky is negotiating a good deal. Patience is a virtue in the pursuit of getting what you want. But research, due diligence, planning, and flexibility are just as important. 1 10938_Bergs_01.c.qxd 12/1/03 4:01 PM Page 2 10938_Bergs_01.c.qxd 12/1/03 4:01 PM Page 3 hen it comes right down to it, the best advice for real estate Winvestors is to practice patience. Though there are many instances when it is necessary to act quickly, patience is a virtue even in situa- tions where time is of the essence. As one case in point, right after the dust cleared from Equity Office Properties’ initial public offering in 1997, the real estate investment trust’s chairman, Sam Zell, began planning a major expansion. Caught in his crosshairs was another real estate investment trust (REIT), Cornerstone Properties, which he wanted to own. Zell knew that although Cornerstone had managed to quickly grow its portfolio of properties, the New York–based REIT was smaller and would have trouble gaining access to the capital mar- kets. It took three years, but Zell finally snared his prey, buying the company for $4.6 billion. The key to this deal was persuading a Dutch pension fund, which owned about 30 percent of Cornerstone, to sell. Although Zell clearly coveted the company’s 15 million square feet of office space, much of which was located in the same cities where Equity Office Properties already had a presence, he took his time with the pension fund. -

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

Spec Sanders: a Memorable Runner in a Forgotten League

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 18, No. 5 (1996) SPEC SANDERS: A MEMORABLE RUNNER IN A FORGOTTEN LEAGUE by Stan Grosshandler (Originally published in Pro Football Digest) "During my career I saw about five or six men I would place in a special category," said Buddy Young, director of Player Relations in Commissioner Pete Rozelle's office. "I won't tell you who they are, but Spec Sanders is one of them. He was in a class by himself!" "He was one of the finest, most complete players I have ever seen. Spec was a late blossomer for he played in the shadow of Pete Layden at Texas and then spent three years in military service. He was a case of a late maturation factor". On Friday night, October 27, 1948, Spec Sanders put on one of the most spectacular and unforgettable shows ever seen on a professional gridiron. A tailback for the New York Yankees of the old All-America Football Conference, Spec carried the ball 24 times for an unsurpassed 225 yards against the Chicago Rockets. The Yankees took the opening kickoff and in 12 plays were on the scoreboard. Sanders went the last 20 yards after flattening a Rocket with a vicious straight arm. Spec accounted for the third TD with a perfect pass, and moments later as he faded for another pass, he was trapped. He squirmed loose and ran 70 yards through the entire Chicago team. "I really do not remember a great deal about the game," recalled Spec. "I do recall Buddy Young taking the opening kickoff of the second half back 95 yards for a touchdown. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

796.33263 lie LL991 f CENTRAL CIRCULATION '- BOOKSTACKS r '.- - »L:sL.^i;:f j:^:i:j r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was borrowed on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutllotlen, UNIVERSITY and undarllnlnfl of books are reasons OF for disciplinary action and may result In dismissal from ILUNOIS UBRARY the University. TO RENEW CAll TEUPHONE CENTEK, 333-8400 AT URBANA04AMPAIGN UNIVERSITY OF ILtlNOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN APPL LiFr: STU0i£3 JAN 1 9 \m^ , USRARy U. OF 1. URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CONTENTS 2 Division of Intercollegiate 85 University of Michigan Traditions Athletics Directory 86 Michigan State University 158 The Big Ten Conference 87 AU-Time Record vs. Opponents 159 The First Season The University of Illinois 88 Opponents Directory 160 Homecoming 4 The Uni\'ersity at a Glance 161 The Marching Illini 6 President and Chancellor 1990 in Reveiw 162 Chief llliniwek 7 Board of Trustees 90 1990 lUinois Stats 8 Academics 93 1990 Game-by-Game Starters Athletes Behind the Traditions 94 1990 Big Ten Stats 164 All-Time Letterwinners The Division of 97 1990 Season in Review 176 Retired Numbers intercollegiate Athletics 1 09 1 990 Football Award Winners 178 Illinois' All-Century Team 12 DIA History 1 80 College Football Hall of Fame 13 DIA Staff The Record Book 183 Illinois' Consensus All-Americans 18 Head Coach /Director of Athletics 112 Punt Return Records 184 All-Big Ten Players John Mackovic 112 Kickoff Return Records 186 The Silver Football Award 23 Assistant -

National College Football Awards Association

College Football Icons among Presenters for The Home Depot College Football Awards Airing Thursday, Dec. 8, at 9 p.m. ET on ESPN Presenters for this year’s The Home Depot College Football Awards - live on Thursday, Dec. 8, at 9 p.m. ET on ESPN – include five College Football Hall of Fame inductees and three former The Home Depot College Football Award winners. The show features the live presentation of nine player awards; the National College Football Awards Association (NCFAA) Contribution to College Football Award to Roy Kramer; The Home Depot Coach of the Year Award; The Allstate AFCA Good Works Team; the Disney Spirit Award; and student-athletes selected to the Walter Camp All-America Team. Presenters include: AWARD PRESENTER FINALISTS Matt Millen Dont’a Hightower, Alabama Chuck Bednarik Award Penn State, Tyrann Mathieu. LSU College Defensive Player of the Year ESPN College Football Analyst Devon Still, Penn State Fred Biletnikoff* Justin Blackmon, Oklahoma State* Biletnikoff Award Florida State, Ryan Broyles, Oklahoma Nation’s Most Outstanding Receiver Pro Football Hall of Fame Robert Woods, USC Judd Groza Randy Bullock, Texas A&M Lou Groza Collegiate Place-Kicker Ohio State, Dustin Hopkins, Florida State Nation’s Most Outstanding Placekicker Son of Lou Groza Caleb Sturgis, Florida Ray Guy* Ray Guy Award Southern Mississippi Ryan Allen, Louisiana Tech Nation’s Most Outstanding Punter Three-time Super Bowl Champion Steven Clark, Auburn Jackson Rice, Oregon Herschel Walker* Andrew Luck, Stanford Maxwell Award 1982 winner, Kellen Moore, -

06FB Guide P151-190.Pmd

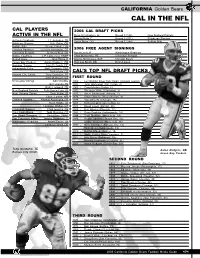

CALIFORNIA Golden Bears CAL IN THE NFL CAL PLAYERS 2006 CAL DRAFT PICKS ACTIVE IN THE NFL Ryan O’Callaghan, OL Round 5 (136) New England Patriots Marvin Philip, C Round 6 (201) Pittsburgh Steelers Arizona Cardinals J.J. Arrington, TB Aaron Merz, OG Round 7 (248) Buffalo Bills Baltimore Ravens Kyle Boller, QB Buffalo Bills Wendell Hunter, LB Carolina Panthers Lorenzo Alexander, DT 2006 FREE AGENT SIGNINGS Cincinnati Bengals Deltha O’Neal, CB David Lonie, P Washington Redskins Dallas Cowboys L.P. Ladouceur, SNAP Chris Manderino, FB Cincinnati Bengals Detroit Lions Nick Harris, P Donnie McCleskey, SAF Chicago Bears Green Bay Packers Aaron Rodgers, QB Harrison Smith, DB Detroit Lions Houston Texans Jerry DeLoach, DE Indianapolis Colts Matt Giordano, SAF Tarik Glenn, OT CAL’S TOP NFL DRAFT PICKS Kansas City Chiefs Tony Gonzalez, TE John Welbourn, OT FIRST ROUND Minnesota Vikings Adimchinobe 1952 - Les Richter (New York Yanks, 2nd pick overall) Echemandu, TB 1953 - John Olszewski (Chi. Cards, 4) Ryan Longwell, PK 1965 - Craig Morton (Dallas, 6) New England Patriots Tully Banta-Cain, LB 1972 - Sherman White (Cincinnati, 2) New Orleans Saints Scott Fujita, LB 1975 - Steve Bartkowski (Atlanta, 1) Chase Lyman, WR 1976 - Chuck Muncie (New Orleans, 3) Oakland Raiders Nnamdi Asomugha, CB 1977 - Ted Albrecht (Chicago, 15) Ryan Riddle, LB 1981 - Rich Campbell (Green Bay, 6) Langston Walker, OT 1984 - David Lewis (Detroit, 20) Pittsburgh Steelers Chidi Iwuoma, CB 1988 - Ken Harvey (Phoenix, 12) Saint Louis Rams Todd Steussie, OT 1993 - Sean Dawkins (Indianapolis, -

HEAD COACHES MOST COACHING WINS Name Years W L T Pct Bowl Wins NATIONAL COACH of the YEAR D

HEAD COACHES MOST COACHING WINS Name Years W L T Pct Bowl Wins NATIONAL COACH OF THE YEAR D. C. Walker 1937-50 (14) 77 51 6 .597 1 (‘46 Gator) Jim Grobe 2001-13 (13) 77 82 0 .484 3 (‘02 Seattle, ‘07 Meineke, ‘08 EagleBank) Dave Clawson 2014-pres. (6) 36 40 0 .474 3 (‘16 Military, ‘17 Belk, ‘18 Birmingham) Bill Dooley 1987-92 (6) 29 36 2 .448 1 (‘92 Independence) Jim Caldwell 1993-00 (8) 26 63 0 .292 1 (‘99 Aloha) Al Groh 1981-86 (6) 26 40 0 .394 LONGEST TENURES Name Years W L T Pct Bowl Games JIM GROBE D. C. Walker 1937-50 (14) 77 51 6 .597 2 (‘46 Gator, ‘49 Dixie) 2006 Jim Grobe 2001-13 (13) 77 82 0 .484 5 (‘02 Seattle, ‘07 FedEx Orange, ‘07 Meineke, ‘08 EagleBank, ‘11 Music City) American Football Coaches Associ- Jim Caldwell 1993-00 (8) 26 63 0 .292 1 (‘99 Aloha) ation Dave Clawson 2014-pres. (6) 36 40 0 .474 4 (‘16 Military, ‘17 Belk, ‘18 Birmingham, ‘19 Pinstripe) Associated Press Al Groh 1981-86 (6) 26 40 0 .394 Bobby Dodd Foundation Bill Dooley 1987-92 (6) 29 36 2 .448 1 (‘92 Independence) CBS Sportsline Sporting News OVERALL RECORD ACC RECORD Name Years W L T Pct W L T Pct W. C. Dowd* (Wake Forest ‘89) 1888 (1) 1 0 0 1.000 W. C. Riddick (Lehigh ‘90) 1889 (1) 3 3 0 .500 W. E. Sikes (Wake Forest ‘91) 1891-93 (3) 6 2 1 .722 Unknown 1895 (1) 0 0 1 .500 JOHN MACKOVIC A. -

Umass Notes.Indd

DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS MEDIA RELATIONS OFFICE 1 College Street, Worcester, MA 01610 Phone: (508) 793-2583 • Fax: (508) 793-2309 2011 Holy Cross Football Holy Cross (0-0, 0-0 PL) vs. #25 Massachusetts (0-0, 0-0 CAA) September 1, 2011 • 8:00 p.m. Fitton Field (23,500) • Worcester, Mass. Let There Be Light Game Day Quick Facts The season-opening game against Massachusetts will mark the fi rst-ever contest to take place under the lights at Fitton Field. In the previous 115 years of Crusader football, there has never been a night game played on Television: CBS Sports Network; James Bates, play-by-play; Aaron the Holy Cross campus. Even though this will be the fi rst home night game Taylor, color; Brooke Collins, sidelines for the Crusaders, the players are not strangers to playing games under the Holy Cross Radio: WTAG 580 AM & 94.9 FM, Worcester; Bob lights. Holy Cross has played three night games over the last three seasons, Fouracre, play-by-play; Gordie Lockbaum, color; www.GoHoly- including contests last season at UMass and Harvard. The Crusaders have Cross.com, internet taken part in a total of 15 night games in their history which are on record, Holy Cross Student Radio: WCHC 88.1 FM, Worcester with the fi rst coming at Louisiana State on Oct. 5, 1940. Series Record: Massachusetts leads, 21-23-5 Last Meeting: Massachusetts 31, Holy Cross 7; Sept. 11, 2010; Amherst, Mass. The Series With Massachusetts This will be the 50th meeting between the Crusaders and the Minutemen on the gridiron, with Massachusetts leading the all-time series 23-21-5. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign !~he Quad s the :enter of :ampus ife 3 . H«H» H 1 i % UI 6 U= tiii L L,._ L-'IA-OHAMPAIGK The 1990 Illinois Football Media Guide • The University of Illinois . • A 100-year Tradition, continued ~> The University at a Glance 118 Chronology 4 President Stanley Ikenberrv • The Athletes . 4 Chancellor Morton Weir 122 Consensus All-American/ 5 UI Board of Trustees All-Big Ten 6 Academics 124 Football Captains/ " Life on Campus Most Valuable Players • The Division of 125 All-Stars Intercollegiate Athletics 127 Academic All-Americans/ 10 A Brief History Academic All-Big Ten 11 Football Facilities 128 Hall of Fame Winners 12 John Mackovic 129 Silver Football Award 10 Assistant Coaches 130 Fighting Illini in the 20 D.I.A. Staff Heisman Voting • 1990 Outlook... 131 Bruce Capel Award 28 Alpha/Numerical Outlook 132 Illini in the NFL 30 1990 Outlook • Statistical Highlights 34 1990 Fighting Illini 134 V early Statistical Leaders • 1990 Opponents at a Glance 136 Individual Records-Offense 64 Opponent Previews 143 Individual Records-Defense All-Time Record vs. Opponents 41 NCAA Records 75 UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 78 UI Travel Plans/ 145 Freshman /Single-Play/ ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN Opponent Directory Regular Season UNIVERSITY OF responsible for its charging this material is • A Look back at the 1989 Season Team Records The person on or before theidue date. 146 Ail-Time Marks renewal or return to the library Sll 1989 Illinois Stats for is $125.00, $300.00 14, Top Performances minimum fee for a lost item 82 1989 Big Ten Stats The 149 Television Appearances journals. -

1956 Topps Football Checklist

1956 Topps Football Checklist 1 John Carson SP 2 Gordon Soltau 3 Frank Varrichione 4 Eddie Bell 5 Alex Webster RC 6 Norm Van Brocklin 7 Packers Team 8 Lou Creekmur 9 Lou Groza 10 Tom Bienemann SP 11 George Blanda 12 Alan Ameche 13 Vic Janowicz SP 14 Dick Moegle 15 Fran Rogel 16 Harold Giancanelli 17 Emlen Tunnell 18 Tank Younger 19 Bill Howton 20 Jack Christiansen 21 Pete Brewster 22 Cardinals Team SP 23 Ed Brown 24 Joe Campanella 25 Leon Heath SP 26 49ers Team 27 Dick Flanagan 28 Chuck Bednarik 29 Kyle Rote 30 Les Richter 31 Howard Ferguson 32 Dorne Dibble 33 Ken Konz 34 Dave Mann SP 35 Rick Casares 36 Art Donovan 37 Chuck Drazenovich SP 38 Joe Arenas 39 Lynn Chandnois 40 Eagles Team 41 Roosevelt Brown RC 42 Tom Fears 43 Gary Knafelc Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Joe Schmidt RC 45 Browns Team 46 Len Teeuws RC, SP 47 Bill George RC 48 Colts Team 49 Eddie LeBaron SP 50 Hugh McElhenny 51 Ted Marchibroda 52 Adrian Burk 53 Frank Gifford 54 Charles Toogood 55 Tobin Rote 56 Bill Stits 57 Don Colo 58 Ollie Matson SP 59 Harlon Hill 60 Lenny Moore RC 61 Redskins Team SP 62 Billy Wilson 63 Steelers Team 64 Bob Pellegrini 65 Ken MacAfee 66 Will Sherman 67 Roger Zatkoff 68 Dave Middleton 69 Ray Renfro 70 Don Stonesifer SP 71 Stan Jones RC 72 Jim Mutscheller 73 Volney Peters SP 74 Leo Nomellini 75 Ray Mathews 76 Dick Bielski 77 Charley Conerly 78 Elroy Hirsch 79 Bill Forester RC 80 Jim Doran 81 Fred Morrison 82 Jack Simmons SP 83 Bill McColl 84 Bert Rechichar 85 Joe Scudero SP 86 Y.A. -

Mcafee Takes a Handoff from Sid Luckman (1947)

by Jim Ridgeway George McAfee takes a handoff from Sid Luckman (1947). Ironton, a small city in Southern Ohio, is known throughout the state for its high school football program. Coach Bob Lutz, head coach at Ironton High School since 1972, has won more football games than any coach in Ohio high school history. Ironton High School has been a regular in the state football playoffs since the tournament’s inception in 1972, with the school winning state titles in 1979 and 1989. Long before the hiring of Bob Lutz and the outstanding title teams of 1979 and 1989, Ironton High School fielded what might have been the greatest gridiron squad in school history. This nearly-forgotten Tiger squad was coached by a man who would become an assistant coach with the Cleveland Browns, general manager of the Buffalo Bills and the second director of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The squad featured three brothers, two of which would become NFL players, in its starting eleven. One of the brothers would earn All-Ohio, All-American and All-Pro honors before his enshrinement in Canton, Ohio. This story is a tribute to the greatest player in Ironton High School football history, his family, his high school coach and the 1935 Ironton High School gridiron squad. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the undefeated and untied Ironton High School football team featuring three players with the last name of McAfee. It was Ironton High School’s first perfect football season, and the school would not see another such gridiron season until 1978.