Callala Bay Shared Path, Shoalhaven Lga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

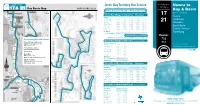

Jervis Bay Territory Bus Service Look for Bus Nowra to Numbers 17 & 21 Bus Route Map NOWRA COACHES Pty

LOOK FOR BUS Jervis Bay Territory Bus Service Look for bus Nowra to numbers 17 & 21 Bus Route Map NOWRA COACHES Pty. Ltd Transport initiative supplied by the Commonwealth of Australia and serviced by Nowra Coaches Bay & Basin Nowra Coaches Pty Ltd - Phone 4423 5244 Buses Servicing Wreck Bay Village to Vincentia – (Weekdays) 17 Departs Nowra Wreck Bay Village 6.25am 9.10am 11.10am 12.45pm 2.17pm Huskisson Summercloud Bay 6.30am 9.15am 11.15am 12.48pm 2.22pm 21 Green Patch 6.40am 9.25am 11.25am 12.58pm 2.32pm Vincentia Jervis Bay Village 6.47am 9.32am 11.32am 1.05pm 2.39pm HMAS Creswell 6.50am 9.35am 11.35am 1.08pm 2.42pm Bay & Basin Visitors Centre 6.55am 9.42am 11.41am 1.13pm 2.48pm Vincentia 7.08am 9.53am 11.51am 1.23pm 2.58pm Central Avenue Bus Departs Tomerong To Nowra (Via Huskisson) 7.10am 9.55am – 1.25pm** 3.00pm **Services Sanctuary Point, St. Georges Basin & Basin View only. Routes (Via Bay & Basin) – – 11.53am – 3.30pm Connecting Bus Operators 732 Wreck Bay Village to Vincentia – Saturday & Sunday Kennedy’s Bus and Coach Departs (Via Bay & Basin) 733 www.kennedystours.com.au See back cover for Tel: 1300 133 477 Wreck Bay Village 9.08am 1.20pm Summercloud Bay 9.13am 1.25pm detailed route descriptions Premier Motor Service Green Patch 9.23am 1.35pm www.premierms.com.au Jervis Bay Village 9.30am 1.42pm Price 50c Tel: 13 34 10 HMAS Creswell 9.33am 1.45pm Visitors Centre 9.38am 1.48pm Shoal Bus Tel: 02 4423 2122 Vincentia 9.48am 1.58pm Email: [email protected] Bus Departs To Nowra (Via Huskisson) 9.50am – Stuarts Coaches (Via -

Booderee National Park Management Plan 2015-2025

(THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK – INSIDE FRONT COVER) Booderee National Park MANAGEMENT PLAN 2015- 2025 Management Plan 2015-2025 3 © Director of National Parks 2015 ISBN: 978-0-9807460-8-2 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9807460-4-4 (Online) This plan is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Director of National Parks. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director of National Parks GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 This management plan sets out how it is proposed the park will be managed for the next ten years. A copy of this plan is available online at: environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/parks-australia/publications. Photography: June Andersen, Jon Harris, Michael Nelson Front cover: Ngudjung Mothers by Ms V. E. Brown SNR © Ngudjung is the story for my painting. “It's about Women's Lore; it's about the connection of all things. It's about the seven sister dreaming, that is a story that governs our land and our universal connection to the dreaming. It is also about the connection to the ocean where our dreaming stories that come from the ocean life that feeds us, teaches us about survival, amongst the sea life. It is stories of mammals, whales and dolphins that hold sacred language codes to the universe. It is about our existence from the first sunrise to present day. We are caretakers of our mother, the land. It is in balance with the universe to maintain peace and harmony. -

Changes to Driver Licence Sanctions in Your CLSD Region

Changes to Driver Licence Sanctions in Your CLSD Region In 2020, Revenue NSW introduced a hardship program focused on First Nations people and young people. As a result, the use of driver licence sanctions for overdue fine debt changed on Monday 28th September 2020 in some locations. How are overdue fines and driver licence sanctions related? If a person has overdue fines, their driver licence may be suspended. The driver licence suspension may be removed if the person: • pays a lump sum to Revenue NSW, or • enters a payment plan with Revenue NSW, or • is approved for a WDO. A driver licence suspension can be applied for multiple reasons, so even after being told that a driver licence suspension for unpaid fines has been removed, people should always double check that it is OK to drive by contacting Service NSW. Driver licence restrictions can also be put on interstate licences and cannot be removed easily. If you have a client in this situation, they should get legal advice. What has changed? Now, driver licence sanctions will not be imposed as a first response to unpaid fines for enforcement orders that were issued on or after 28 September 2020 to First Nations people and young people who live in the target locations. What are the target locations? Locations that the Australian Bureau of Statistics classifies as: • very remote, • remote • outer regional, and • Inner regional post codes where at least 9% of the population are First Nations People. Included target locations on the South Coast are the towns of Batemans Bay, Bega, Bodalla, Eden, Eurobodalla, Mogo, Narooma, Nowra Hill, Nowra Naval PO, Merimbula, Pambula, Tilba and Wallaga Lake. -

Agenda of Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group

Meeting Agenda Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group Meeting Date: Monday, 10 May, 2021 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Please note: Council’s Code of Meeting Practice permits the electronic recording and broadcast of the proceedings of meetings of the Council which are open to the public. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies 2. Confirmation of Minutes • Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group - 24 March 2021 ............................................. 1 3. Presentations TA21.11 Rockclimbing - Rob Crow (Owner) - Climb Nowra A space in the agenda for Rob Crow to present on Climbing in the region as requested by STAG. 4. Reports TA21.12 Tourism Manager Update ............................................................................ 3 TA21.13 Election of Office Bearers............................................................................ 6 TA21.14 Visitor Services Update ............................................................................. 13 TA21.15 Destination Marketing ............................................................................... 17 TA21.16 Chair's Report ........................................................................................... 48 TA21.17 River Festival Update ................................................................................ 50 TA21.18 Event and Investment Report ................................................................... -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Agenda of Strategy and Assets Committee

Meeting Agenda Strategy and Assets Committee Meeting Date: Tuesday, 18 May, 2021 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Membership (Quorum - 5) Clr John Wells - Chairperson Clr Bob Proudfoot All Councillors Chief Executive Officer or nominee Please note: The proceedings of this meeting (including presentations, deputations and debate) will be webcast and may be recorded and broadcast under the provisions of the Code of Meeting Practice. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies / Leave of Absence 2. Confirmation of Minutes • Strategy and Assets Committee - 13 April 2021 ........................................................ 1 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Mayoral Minute 5. Deputations and Presentations 6. Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice SA21.73 Notice of Motion - Creating a Dementia Friendly Shoalhaven ................... 23 SA21.74 Notice of Motion - Reconstruction and Sealing Hames Rd Parma ............. 25 SA21.75 Notice of Motion - Cost of Refurbishment of the Mayoral Office ................ 26 SA21.76 Notice of Motion - Madeira Vine Infestation Transport For NSW Land Berry ......................................................................................................... 27 SA21.77 Notice of Motion - Possible RAAF World War 2 Memorial ......................... 28 7. Reports CEO SA21.78 Application for Community -

Redistribution of New South Wales Into Electoral Divisions FEBRUARY 2016

Redistribution of New South Wales into electoral divisions FEBRUARY 2016 Report of the augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in 18 languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-44-2 © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 © State of New South Wales 2016 The report should be cited as augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales, Redistribution of New South Wales into electoral divisions. 15_0526 The augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales (the augmented Electoral Commission) has undertaken a redistribution of New South Wales. In developing and considering the impacts of the redistribution, the augmented Electoral Commission has satisfied itself that the electoral divisions comply with the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The augmented Electoral Commission commends its redistribution for New South Wales. This report is prepared to fulfil the requirements of section 74 of the Electoral Act. -

Regional Overview

1 Regional Overview Population: 172,650 persons (2016 est. resident population) Growth Rate: 3.74% (2011 – 2016) 0.51% average annual growth Key Industries: Retail, Health Care and Social Assistance, Construction, Manufacturing, Defence, Tourism and Agriculture Number of Businesses by Industry – (top 10 shown) Construction 2484 Agriculture, forestry and fishing 1250 Rental, hiring and real estate services 1165 Retail trade 1101 Professional, scientific and technical services 989 Tourism 863 Financial and insurance services 647 Health care and social assistance 638 Transport, postal and warehousing 631 Other services 613 Total Businesses FSC (2014) 12,123 Council Areas: City of Shoalhaven, Eurobodalla Shire and Bega Valley Shire Location & Environment The Far South Coast (FSC) of NSW is a region covering 14,230sqkm of coastal land from Berry in the north to the NSW/ Victoria border in the south. 2 It is made up of three local government areas – Shoalhaven City, Eurobodalla Shire and Bega Valley Shire. The FSC is strategically located between the nation’s main capital cities, approximately 2-5 hours from Sydney, 6-10 hours from Melbourne and just 2 hours from Canberra. The FSC is renowned for its natural beauty with nearly 400 km of coastline; numerous marine parks, thirty one national park areas and extensive areas of state parks. The region generally has mild, pleasant weather. The summers are warm with an average maximum of 27°C while the winters generally have a minimum range from 1°C to 12°C. (Bureau of Meteorology). People & Community The estimated resident population of the FSC as at 30 June 2016 was 172,500 persons. -

BOAT RAMPS in the SHOALHAVEN

BOAT RAMPS in the SHOALHAVEN All ramps are concrete unless stated otherwise Location Waterway Notes BASIN VIEW Basin View Parade into St. Georges Basin Jetty BAWLEY POINT Tingira Avenue (Bawley Beach) into sea Natural ramp – 4WD BENDALONG Washerwoman’s Beach into sea BERRY Coolangatta Road into Broughton Creek BOMADERRY Off Bolong Road into Bomaderry Creek Low level landing BURRILL LAKE Kendall Crescent into Burrill Lake BURRILL LAKE Maria Avenue into Burrill Lake Floating pontoon BURRILL LAKE Moore Street into Burrill Lake Natural ramp CALLALA BAY Watt Street into Jervis Bay CROOKHAVEN HEADS Prince Edward Avenue Low level landing CULBURRA BEACH West Crescent into Lake Wollumboola Natural ramp – light boats CUNJURONG POINT York Street into Lake Conjola Light boats, 4WD CURRARONG Warrain Crescent into creek CURRARONG Yalwal Street to ocean Day time use only DURRAS NORTH Bundilla Park into Durras Lake Natural ramp – light boats EROWAL BAY Naval Parade into St. Georges Basin FISHERMAN’S PARADISE Off Anglers Parade into Lake Conjola GREENWELL POINT West Street into Crookhaven River GREENWELL POINT Adelaide Street into Crookhaven River Floating pontoon GREENWELL POINT Haiser Road into Crookhaven River (Private Facility) Bowling Club HONEYMOON BAY Bindijine Beach (Defence land) Natural ramp – across sand HYAMS BEACH Off Cyrus Street into Jervis Bay Hand Launching Only KILLARNEY Off Killarney Road into Lake Conjola (Private Facility) Fees apply KINGS POINT Off Edward Avenue into Burrill Lake (Ulladulla Ski Club) (daily tariff) KIOLOA Scerri -

Independent Review Panel

INDEPENDENT REVIEW PANEL SOUTH COAST SENSITIVE URBAN LANDS REVIEW _________________________________________________________________________ REPORT TO THE HONOURABLE FRANK SARTOR MP MINISTER FOR PLANNING OCTOBER 2006 SOUTH COAST INDEPENDENT REVIEW PANEL The Hon Frank Sartor MP Minister for Planning Level 34, Governor Macquarie Tower 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Minister, RE: SOUTH COAST INDEPENDENT REVIEW PANEL Following the release of the Draft South Coast Regional Strategy, you appointed me to chair a Panel to investigate the suitability for development of some sixteen sites in the region. We received some 188 submissions and held public hearings over six days in the towns of Nowra, Batemans Bay and Bega as well as in Sydney. Fifty one people appeared at the public hearings. Having given due regard to all the submissions, we present our report, with recommendations, on each of the sites. It is important to read the recommendations along with the body of the report, especially the planning assessment and the environmental assessment sections of each site’s evaluation. We have also suggested some planning issues for further discussion that arose during our investigations and deliberations. My colleagues on the Panel, Mr Vince Berkhout and Dr David Robertson have brought considerable experience and expertise to the task, and we are unanimous in our recommendations. Of the total area already zoned for potential development (about 2200ha) we recommended less than 30% to be developed. Of all the land investigated (about 5900ha) we recommended that almost 30% be for environmental conservation. We were very ably assisted in all the preparations for our meetings and public hearings and preparation of the report by Mr Paul Freeman. -

Race Information

RACE INFORMATION Welcome from the New South Wales Government A warm welcome to athletes and supporters visiting Jervis Bay on the beautiful South Coast of NSW for the 2015 XTERRA Asia-Pacific Championships. The NSW Government proudly secured this event until 2016, through its tourism and major events agency Destination NSW. The XTERRA Asia-Pacific Championship takes the traditional triathlon off-road, and welcomes some of the world’s best and toughest athletes who will test their skills and endurance on the region’s beaches and trails. The weekend-long festival also gives casual participants the opportunity to compete in a sprint distance off-road triathlon, trail run, or relay team competition. The NSW South Coast is a haven for surfers, cyclists, runners and nature lovers, and a fitting location to host this event. Competitors will take in some spectacular scenery en route, and visitors will be charmed by the local hospitality and the area’s beautiful natural attractions including Jervis Bay Marine Park and Booderee National Park, as well as its headlands, cliff top walking trails and native forests. Best of luck to all competitors for the 2015 XTERRA Asia-Pacific Championships, and have a wonderful stay in Jervis Bay. Thank you for joining the XTERRA global family at the 2nd annual XTERRA Asia-Pacific Championship. We look forward to seeing you in Jervis Bay. The following Race Information has everything you will need to know to prepare for the race and have a great race day. Our team is available to answer any additional queries you have so please do not hesitate to contact us. -

5 Bunaan Close WRECK BAY JBT 2540

5 Bunaan Close WRECK BAY JBT 2540 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 3 WBACC location ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Organisational Chart ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Purposes........................................................................................................................................................... 6 WBACC’s Vision .......................................................................................................................................... 6 WBACC’s Goals ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Provide more Housing and Improve Living Standards .................................................................. 7 Continue to maintain Good Governance Principles ......................................................................... 7 Obtain Sole Ownership of Land and Waters of Jervis Bay ........................................................ 8 Undertake Skills Analysis and Skills Training ................................................................................ 8 Implement New Management Structure ........................................................................................