Drugs for the Treatment of Menopausal Symptoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

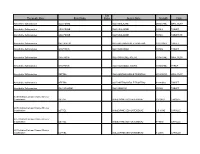

Therapeutic Class Brand Name P a Status Generic

P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 250MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET DR Absorbable Sulfonamides BACTRIM DS SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 800-160MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML SYRUP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 200-40MG/5 ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 400-80MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides SULFADIAZINE SULFADIAZINE 500MG TABLET ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-20MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 2.5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-20MG CAPSULE P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-40MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-40MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 10MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 20MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE -

And Active-Controlled Phase 3 Study of Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis

Christiansen et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2010, 11:130 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/11/130 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access SafetyResearch article of bazedoxifene in a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled phase 3 study of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis Claus Christiansen*1, Charles H Chesnut III2, Jonathan D Adachi3, Jacques P Brown4, César E Fernandes5, Annie WC Kung6, Santiago Palacios7, Amy B Levine8, Arkadi A Chines8 and Ginger D Constantine8 Abstract Background: We report the safety findings from a 3-year phase 3 study (NCT00205777) of bazedoxifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator under development for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Methods: Healthy postmenopausal osteoporotic women (N = 7,492; mean age, 66.4 years) were randomized to daily doses of bazedoxifene 20 or 40 mg, raloxifene 60 mg, or placebo for 3 years. Safety and tolerability were assessed by adverse event (AE) reporting and routine physical, gynecologic, and breast examination. Results: Overall, the incidence of AEs, serious AEs, and discontinuations due to AEs in the bazedoxifene groups was not different from that seen in the placebo group. The incidence of hot flushes and leg cramps was higher with bazedoxifene or raloxifene compared with placebo. The rates of cardiac disorders and cerebrovascular events were low and evenly distributed among groups. Venous thromboembolic events, primarily deep vein thromboses, were more frequently reported in the active treatment groups compared with the placebo group; rates were similar with bazedoxifene and raloxifene. Bazedoxifene showed a neutral effect on the breast and an excellent endometrial safety profile. The incidence of fibrocystic breast disease was lower with bazedoxifene 20 and 40 mg versus raloxifene or placebo. -

Postmenopausal Pharmacotherapy Newsletter

POSTMENOPAUSAL PHARMACOTHERAPY September, 1999 As Canada's baby boomers age, more and more women will face the option of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT). The HIGHLIGHTS decision can be a difficult one given the conflicting pros and cons. M This RxFiles examines the role and use of HRT, as well as newer Long term HRT carries several major benefits but also risks SERMS and bisphosphonates in post-menopausal (PM) patients. which should be evaluated on an individual and ongoing basis MContinuous ERT is appropriate for women without a uterus HRT MWomen with a uterus should receive progestagen (at least 12 HRT is indicated for the treatment of PM symptoms such as days per month or continuous low-dose) as part of their HRT vasomotor disturbances and urogenital atrophy, and is considered MLow-dose ERT (CEE 0.3mg) + Ca++ appears to prevent PMO primary therapy for prevention and treatment of postmenopausal MBisphosphinates (e.g. alendronate, etidronate) and raloxifene are osteoporosis (PMO).1 Contraindications are reviewed in Table 2. alternatives to HRT in treating and preventing PMO Although HRT is contraindicated in women with active breast or M"Natural" HRT regimens can be compounded but data is lacking uterine cancer, note that a prior or positive family history of these does not necessarily preclude women from receiving HRT.1 Comparative Safety: Because of differences between products, some side effects may be alleviated by switching from one product Estrogen Replacement Therapy (ERT) 2 to another, particularly from equine to plant sources or from oral to Naturally secreted estrogens include: topical (see Table 3 - Side Effects & Their Management). -

Affect Breast Cancer Risk

HOW HORMONES AFFECT BREAST CANCER RISK Hormones are chemicals made by the body that control how cells and organs work. Estrogen is a female hormone made mainly in the ovaries. It’s important for sexual development and other body functions. From your first monthly period until menopause, estrogen stimulates normal breast cells. A higher lifetime exposure to estrogen may increase breast cancer risk. For example, your risk increases if you start your period at a young age or go through menopause at a later age. Other hormone-related risks are described below. Menopausal hormone therapy Pills Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is The U.S. Food and Drug Administration also known as postmenopausal hormone (FDA) recommends women use the lowest therapy and hormone replacement dose that eases symptoms for the shortest therapy. Many women use MHT pills to time needed. relieve hot flashes and other menopausal Any woman currently taking or thinking symptoms. MHT should be used at the Birth control about taking MHT pills should talk with her lowest dose and for the shortest time pills (oral doctor about the risks and benefits. contraceptives) needed to ease menopausal symptoms. Long-term use can increase breast cancer Vaginal creams, suppositories Current or recent use risk and other serious health conditions. and rings of birth control pills There are 2 main types of MHT pills: slightly increases breast Vaginal forms of MHT do not appear to cancer risk. However, estrogen plus progestin and estrogen increase the risk of breast cancer. However, this risk is quite small alone. if you’ve been diagnosed with breast cancer, vaginal estrogen rings and suppositories are because the risk of Estrogen plus progestin MHT breast cancer for most better than vaginal estrogen creams. -

Tamoxifen, Raloxifene Upheld for Prevention

38 WOMEN’S HEALTH MAY 1, 2010 • FAMILY PRACTICE NEWS Tamoxifen, Raloxifene Upheld for Prevention BY KERRI WACHTER 9,736 on tamoxifen and 9,754 on ralox- 1.24, which was significant (P = .01). Both events) did not appear to be as effective ifene. The differences in numbers are due drugs reduced the risk of invasive breast as tamoxifen (57 events) in preventing WASHINGTON — Tamoxifen and to a combination of loss during follow- cancer by roughly 50% in the original re- noninvasive breast cancer (P = .052). raloxifene offer women at high risk of up or follow-up data becoming available port (median follow-up 47 months). “Now with additional follow-up, those developing breast cancer two effective for women who were lost to follow-up “We have estimated, however, that differences have narrowed,” he said. At options to prevent the disease, based on in the original report. Women on ta- this difference in the raloxifene-treated 8 years, there was no statistical signifi- 8 years of follow-up data for more than moxifen received 20 mg/day and those group represents 76% of tamoxifen’s cance between the two groups with a 19,000 women in the STAR trial. on raloxifene received 60 mg/day. chemopreventative benefit, which trans- risk ratio of 1.22 (P = .12). The relative While tamoxifen proved significantly At an average follow-up of 8 years, the lates into at 38% reduction in invasive risk of 1.22 favors tamoxifen, but ralox- more effective in preventing invasive breast relative risk of invasive breast cancer on breast cancers,” Dr. -

Alpha-Fetoprotein: the Major High-Affinity Estrogen Binder in Rat

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 73, No. 5, pp. 1452-1456, May 1976 Biochemistry Alpha-fetoprotein: The major high-affinity estrogen binder in rat uterine cytosols (rat alpha-fetoprotein/estrogen receptors) JOSE URIEL, DANIELLE BOUILLON, CLAUDE AUSSEL, AND MICHELLE DUPIERS Institut de Recherches Scientifiques sur le Cancer, Boite Postale No. 8, 94800 Villejuif, France Communicated by Frangois Jacob, February 3, 1976 ABSTRACT Evidence is presented that alpha-fetoprotein nates in hypotonic solutions, whereas in salt concentrations (AFP), a serum globulin, accounts mainly, if not entirely, for above 0.2 M the 4S complex is by far the major binding enti- the high estrogen-binding properties of uterine cytosols from immature rats. By the use of specific immunoadsorbents to ty. AFP and by competitive assays with unlabeled steroids and The relatively high levels of serum AFP in immature rats pure AFP, it has been demonstrated that in hypotonic cyto- prompted us to explore the contribution of AFP to the estro- sols AFP is present partly as free protein with a sedimenta- gen-binding capacity of uterine homogenates. The results tion coefficient of about 4-5 S and partly in association with obtained with specific anti-AFP immunoadsorbents (12, 13) some intracellular constituent(s) to form an 8S estrogen-bind- provided evidence that at low salt concentrations,'AFP ac-' ing entity. The AFP - 8S transformation results in a loss of antigenic reactivity to antibodies against AFP and a signifi- counts for most of the estrogen-binding capacity associated cant change in binding specificity. This change in binding with the 4-5S macromolecular complex. -

Antiestrogenic Action of Dihydrotestosterone in Mouse Breast

Antiestrogenic action of dihydrotestosterone in mouse breast. Competition with estradiol for binding to the estrogen receptor. R W Casey, J D Wilson J Clin Invest. 1984;74(6):2272-2278. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI111654. Research Article Feminization in men occurs when the effective ratio of androgen to estrogen is lowered. Since sufficient estrogen is produced in normal men to induce breast enlargement in the absence of adequate amounts of circulating androgens, it has been generally assumed that androgens exert an antiestrogenic action to prevent feminization in normal men. We examined the mechanisms of this effect of androgens in the mouse breast. Administration of estradiol via silastic implants to castrated virgin CBA/J female mice results in a doubling in dry weight and DNA content of the breast. The effect of estradiol can be inhibited by implantation of 17 beta-hydroxy-5 alpha-androstan-3-one (dihydrotestosterone), whereas dihydrotestosterone alone had no effect on breast growth. Estradiol administration also enhances the level of progesterone receptor in mouse breast. Within 4 d of castration, the progesterone receptor virtually disappears and estradiol treatment causes a twofold increase above the level in intact animals. Dihydrotestosterone does not compete for binding to the progesterone receptor, but it does inhibit estrogen-mediated increases of progesterone receptor content of breast tissue cytosol from both control mice and mice with X-linked testicular feminization (tfm)/Y. Since tfm/Y mice lack a functional androgen receptor, we conclude that this antiestrogenic action of androgen is not mediated by the androgen receptor. Dihydrotestosterone competes with estradiol for binding to the cytosolic estrogen receptor of mouse breast, […] Find the latest version: https://jci.me/111654/pdf Antiestrogenic Action of Dihydrotestosterone in Mouse Breast Competition with Estradiol for Binding to the Estrogen Receptor Richard W. -

Memorandum Date: June 6, 2014

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Memorandum Date: June 6, 2014 From: Bisphenol A (BPA) Joint Emerging Science Working Group Smita Baid Abraham, M.D. ∂, M. M. Cecilia Aguila, D.V.M. ⌂, Steven Anderson, Ph.D., M.P.P.€* , Jason Aungst, Ph.D.£*, John Bowyer, Ph.D. ∞, Ronald P Brown, M.S., D.A.B.T.¥, Karim A. Calis, Pharm.D., M.P.H. ∂, Luísa Camacho, Ph.D. ∞, Jamie Carpenter, Ph.D.¥, William H. Chong, M.D. ∂, Chrissy J Cochran, Ph.D.¥, Barry Delclos, Ph.D.∞, Daniel Doerge, Ph.D.∞, Dongyi (Tony) Du, M.D., Ph.D. ¥, Sherry Ferguson, Ph.D.∞, Jeffrey Fisher, Ph.D.∞, Suzanne Fitzpatrick, Ph.D. D.A.B.T. £, Qian Graves, Ph.D.£, Yan Gu, Ph.D.£, Ji Guo, Ph.D.¥, Deborah Hansen, Ph.D. ∞, Laura Hungerford, D.V.M., Ph.D.⌂, Nathan S Ivey, Ph.D. ¥, Abigail C Jacobs, Ph.D.∂, Elizabeth Katz, Ph.D. ¥, Hyon Kwon, Pharm.D. ∂, Ifthekar Mahmood, Ph.D. ∂, Leslie McKinney, Ph.D.∂, Robert Mitkus, Ph.D., D.A.B.T.€, Gregory Noonan, Ph.D. £, Allison O’Neill, M.A. ¥, Penelope Rice, Ph.D., D.A.B.T. £, Mary Shackelford, Ph.D. £, Evi Struble, Ph.D.€, Yelizaveta Torosyan, Ph.D. ¥, Beverly Wolpert, Ph.D.£, Hong Yang, Ph.D.€, Lisa B Yanoff, M.D.∂ *Co-Chair, € Center for Biologics Evaluation & Research, £ Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, ∂ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, ¥ Center for Devices and Radiological Health, ∞ National Center for Toxicological Research, ⌂ Center for Veterinary Medicine Subject: 2014 Updated Review of Literature and Data on Bisphenol A (CAS RN 80-05-7) To: FDA Chemical and Environmental Science Council (CESC) Office of the Commissioner Attn: Stephen M. -

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Enhance CNS Remyelination Independent of Estrogen Receptors

This Accepted Manuscript has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. Research Articles: Cellular/Molecular Selective estrogen receptor modulators enhance CNS remyelination independent of estrogen receptors Kelsey A. Rankin1, Feng Mei1, Kicheol Kim1, Yun-An A. Shen1, Sonia R. Mayoral1, Caroline Desponts2, Daniel S. Lorrain2, Ari J. Green1, Sergio E. Baranzini1, Jonah R. Chan1 and Riley Bove1 1University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, Department of Neurology 2Inception Sciences, San Diego, CA https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1530-18.2019 Received: 11 June 2018 Revised: 17 January 2019 Accepted: 20 January 2019 Published: 29 January 2019 Author contributions: K.R., Y.-A.A.S., A.J.G., J.R.C., and R.B. designed research; K.R., F.M., K.K., Y.- A.A.S., S.R.M., C.D., D.S.L., and S.B. performed research; K.R. analyzed data; K.R. wrote the first draft of the paper; K.R., J.R.C., and R.B. edited the paper; K.R. wrote the paper; F.M. and J.R.C. contributed unpublished reagents/analytic tools. Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests. We would like to thank the Innovation Program for Remyelination and Repair at the Weill Institute for Neurosciences at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [R01NS062796, R01NS097428, R01NS095889, R01NS088155], the National Multiple Sclerosis Society [RG5203A4], The Adelson Medical Research Foundation: ANDP (A130141), the Heidrich Family and Friends and the Rachleff Family Endowments. -

Bazedoxifene–Conjugated Estrogens for Treating Endometriosis Endometriosis: Nina S

Endometriosis: Case Report Bazedoxifene–Conjugated Estrogens Teaching Points for Treating Endometriosis 1. The estrogen receptor (ER) is a definitive down- stream target in endometriosis. As an endometrial ER antagonist, bazedoxifene assures not only block- Valerie A. Flores, MD, ade of estrogen binding, but it also has the ability to Nina S. Stachenfeld, PhD, degrade the receptor. This unique property of baze- and Hugh S. Taylor, MD doxifene blocks estrogen action and makes it an attractive treatment option for endometriosis. 2. Conjugated estrogens paired with bazedoxifene do BACKGROUND: Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder not require a progestin to block endometrial affecting 6–10% of reproductive-aged women. First-line growth, thus avoiding the side effects associated therapies are progestin-based regimens; however, failure with progestin-based regimens. 08/19/2018 on BhDMf5ePHKbH4TTImqenVGLGjjqParD6K7Nl5tTGGFqgjMmLRmuIlIgbkUbgVXoQ by http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal from Downloaded rates are high, often requiring alternative hormonal agents, each with unfavorable side effects. Bazedoxifene with con- ’ 1 Downloaded that can have a significant effect on patients lives. jugated estrogens is approved for treatment of menopausal Treatment consists of agents that induce atrophy of symptoms, and use in animal studies has demonstrated from regression of endometriotic lesions. As such, it represents endometriotic lesions. There is tremendous need for http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal a potential treatment option for endometriosis. therapies that are effective, have favorable side effect profiles, and can be used long term in women with CASE: A patient with stage III endometriosis referred for symptomatic endometriosis, especially for those not management of dysmenorrhea and cyclic pelvic pain was treated with 20 mg bazedoxifene and 0.45 mg conjugated responding to progestin-based regimens. -

Estrone-Compound-Pal-011921

ESTRONE COMPOUND What is this medicine? Estrone (es-trohn) E1 Estrone is a hormone derived from yams and may be given to women who no longer produce a sufficient amount on their own. It may be used to reduce menopause symptoms (e.g., hot flashes, vaginal dryness). It may be used to help prevent bone loss. It may also be used for other conditions as determined by your doctor. Compounded Drug Forms: BLA tablet, sublingual tablet, fast-burst sublingual tablet, vaginal tablet, troche, vaginal suppository, cream, gel What should I tell my health care provider before I take this medicine? Allergy to estrone Pregnant or breastfeeding Have undiagnosed severe vaginal bleeding Active cancer of the breast or uterus A history of blood clots, stroke or heart attacks Smoking while using this medication may increase your risk of blood clots. Have liver dysfunction or disease How should I use this medicine? Follow the package directions provided by Belmar Pharmacy and by your prescriber. Your dosage is based on your medical condition and response to therapy. Follow the dosing schedule provided carefully. Oral tablets may be taken with or without food, if it upsets your stomach take it with a small meal. Sublingual tablets and fast-burst sublingual tablets should be placed under the tongue or between the cheek and gums and held in place until fully dissolved. Avoid swallowing saliva to ensure best absorption into the blood stream. Avoid eating or drinking 15 minutes before or after taking sublingual tablet. Topical products can be applied to the inner arm, upper thigh, back of the knee, tops of the feet and inner wrists. -

Estrogen Agents, Oral-Transdermal

GEORGIA MEDICAID FEE-FOR-SERVICE ESTROGEN AGENTS, ORAL - TRANSDERMAL PA SUMMARY Preferred Non-Preferred Oral Estrogens Estradiol generic n/a Menest (esterified estrogens) Premarin (estrogens, conjugated) Oral Estrogen/Progestin Combinations Angeliq (drospirenone/estradiol) Bijuva (estradiol/progesterone) Estradiol/norethindrone and all generics for Activella Norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol and all generics for Femhrt Low Dose 0.5/2.5 (norethindrone/ethinyl Femhrt Low Dose estradiol) Jinteli and all generics for Femhrt 1/5 (norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol) Prefest (estradiol/norgestimate) Premphase (conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone) Prempro (conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone) Topical Estrogens Alora (estradiol transdermal patch) Divigel (estradiol topical gel) Estradiol transdermal patch (generic Climara) Elestrin (estradiol topical gel) Evamist (estradiol topical spray solution) Estradiol transdermal patch (generic Vivelle-Dot) Menostar (estradiol transdermal patch) Minivelle (estradiol transdermal patch) Vivelle-Dot (estradiol transdermal patch) Topical Estrogens/Progestin Combination Climara Pro (estradiol/levonorgestrel transdermal patch) n/a Combipatch (estradiol/norethindrone transdermal patch) Oral Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERMs) Raloxifene generic Duavee (conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene) Osphena (ospemifene) LENGTH OF AUTHORIZATION: 1 year PA CRITERIA: Bijuva ❖ Approvable for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause in women with an intact uterus who have experienced inadequate response, allergies, contraindications, drug-drug interactions or intolerable side effects to at least two preferred oral estrogen/progestin combination products. Revised 6/29/2020 Norethindrone/Ethinyl Estradiol and All Generics for Femhrt Low Dose ❖ Prescriber must submit a written letter of medical necessity stating the reasons at least two preferred oral estrogen/progestin combination products, one of which must be brand Femhrt Low Dose, are not appropriate for the member.