Arxiv:0909.2359V3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observations of Wavefunction Collapse and the Retrospective Application of the Born Rule

Observations of wavefunction collapse and the retrospective application of the Born rule Sivapalan Chelvaniththilan Department of Physics, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka [email protected] Abstract In this paper I present a thought experiment that gives different results depending on whether or not the wavefunction collapses. Since the wavefunction does not obey the Schrodinger equation during the collapse, conservation laws are violated. This is the reason why the results are different – quantities that are conserved if the wavefunction does not collapse might change if it does. I also show that using the Born Rule to derive probabilities of states before a measurement given the state after it (rather than the other way round as it is usually used) leads to the conclusion that the memories that an observer has about making measurements of quantum systems have a significant probability of being false memories. 1. Introduction The Born Rule [1] is used to determine the probabilities of different outcomes of a measurement of a quantum system in both the Everett and Copenhagen interpretations of Quantum Mechanics. Suppose that an observer is in the state before making a measurement on a two-state particle. Let and be the two states of the particle in the basis in which the observer makes the measurement. Then if the particle is initially in the state the state of the combined system (observer + particle) can be written as In the Copenhagen interpretation [2], the state of the system after the measurement will be either with a 50% probability each, where and are the states of the observer in which he has obtained a measurement of 0 or 1 respectively. -

The Statistical Interpretation of Entangled States B

The Statistical Interpretation of Entangled States B. C. Sanctuary Department of Chemistry, McGill University 801 Sherbrooke Street W Montreal, PQ, H3A 2K6, Canada Abstract Entangled EPR spin pairs can be treated using the statistical ensemble interpretation of quantum mechanics. As such the singlet state results from an ensemble of spin pairs each with an arbitrary axis of quantization. This axis acts as a quantum mechanical hidden variable. If the spins lose coherence they disentangle into a mixed state. Whether or not the EPR spin pairs retain entanglement or disentangle, however, the statistical ensemble interpretation resolves the EPR paradox and gives a mechanism for quantum “teleportation” without the need for instantaneous action-at-a-distance. Keywords: Statistical ensemble, entanglement, disentanglement, quantum correlations, EPR paradox, Bell’s inequalities, quantum non-locality and locality, coincidence detection 1. Introduction The fundamental questions of quantum mechanics (QM) are rooted in the philosophical interpretation of the wave function1. At the time these were first debated, covering the fifty or so years following the formulation of QM, the arguments were based primarily on gedanken experiments2. Today the situation has changed with numerous experiments now possible that can guide us in our search for the true nature of the microscopic world, and how The Infamous Boundary3 to the macroscopic world is breached. The current view is based upon pivotal experiments, performed by Aspect4 showing that quantum mechanics is correct and Bell’s inequalities5 are violated. From this the non-local nature of QM became firmly entrenched in physics leading to other experiments, notably those demonstrating that non-locally is fundamental to quantum “teleportation”. -

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit Sasu Tuohino B. Sc. Thesis Department of Physical Sciences Theoretical Physics University of Oulu 2017 Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Classical network theory4 2.1 From electromagnetic fields to circuit elements.........4 2.2 Generalized flux and charge....................6 2.3 Node variables as degrees of freedom...............7 3 Hamiltonians for electric circuits8 3.1 LC Circuit and DC voltage source................8 3.2 Cooper-Pair Box.......................... 10 3.2.1 Josephson junction.................... 10 3.2.2 Dynamics of the Cooper-pair box............. 11 3.3 Transmon qubit.......................... 12 3.3.1 Cavity resonator...................... 12 3.3.2 Shunt capacitance CB .................. 12 3.3.3 Transmon Lagrangian................... 13 3.3.4 Matrix notation in the Legendre transformation..... 14 3.3.5 Hamiltonian of transmon................. 15 4 Classical dynamics of transmon qubit 16 4.1 Equations of motion for transmon................ 16 4.1.1 Relations with voltages.................. 17 4.1.2 Shunt resistances..................... 17 4.1.3 Linearized Josephson inductance............. 18 4.1.4 Relation with currents................... 18 4.2 Control and read-out signals................... 18 4.2.1 Transmission line model.................. 18 4.2.2 Equations of motion for coupled transmission line.... 20 4.3 Quantum notation......................... 22 5 Numerical solutions for equations of motion 23 5.1 Design parameters of the transmon................ 23 5.2 Resonance shift at nonlinear regime............... 24 6 Conclusions 27 1 Abstract The focus of this thesis is on classical dynamics of a transmon qubit. First we introduce the basic concepts of the classical circuit analysis and use this knowledge to derive the Lagrangians and Hamiltonians of an LC circuit, a Cooper-pair box, and ultimately we derive Hamiltonian for a transmon qubit. -

SIMULATED INTERPRETATION of QUANTUM MECHANICS Miroslav Súkeník & Jozef Šima

SIMULATED INTERPRETATION OF QUANTUM MECHANICS Miroslav Súkeník & Jozef Šima Slovak University of Technology, Radlinského 9, 812 37 Bratislava, Slovakia Abstract: The paper deals with simulated interpretation of quantum mechanics. This interpretation is based on possibilities of computer simulation of our Universe. 1: INTRODUCTION Quantum theory and theory of relativity are two fundamental theories elaborated in the 20th century. In spite of the stunning precision of many predictions of quantum mechanics, its interpretation remains still unclear. This ambiguity has not only serious physical but mainly philosophical consequences. The commonest interpretations include the Copenhagen probability interpretation [1], many-words interpretation [2], and de Broglie-Bohm interpretation (theory of pilot wave) [3]. The last mentioned theory takes place in a single space-time, is non - local, and is deterministic. Moreover, Born’s ensemble and Watanabe’s time-symmetric theory being an analogy of Wheeler – Feynman theory should be mentioned. The time-symmetric interpretation was later, in the 60s re- elaborated by Aharonov and it became in the 80s the starting point for so called transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics. More modern interpretations cover a spontaneous collapse of wave function (here, a new non-linear component, causing this collapse is added to Schrödinger equation), decoherence interpretation (wave function is reduced due to an interaction of a quantum- mechanical system with its surroundings) and relational interpretation [4] elaborated by C. Rovelli in 1996. This interpretation treats the state of a quantum system as being observer-dependent, i.e. the state is the relation between the observer and the system. Relational interpretation is able to solve the EPR paradox. -

Derivation of the Born Rule from Many-Worlds Interpretation and Probability Theory K

Derivation of the Born rule from many-worlds interpretation and probability theory K. Sugiyama1 2014/04/16 The first draft 2012/09/26 Abstract We try to derive the Born rule from the many-worlds interpretation in this paper. Although many researchers have tried to derive the Born rule (probability interpretation) from Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI), it has not resulted in the success. For this reason, derivation of the Born rule had become an important issue of MWI. We try to derive the Born rule by introducing an elementary event of probability theory to the quantum theory as a new method. We interpret the wave function as a manifold like a torus, and interpret the absolute value of the wave function as the surface area of the manifold. We put points on the surface of the manifold at a fixed interval. We interpret each point as a state that we cannot divide any more, an elementary state. We draw an arrow from any point to any point. We interpret each arrow as an event that we cannot divide any more, an elementary event. Probability is proportional to the number of elementary events, and the number of elementary events is the square of the number of elementary state. The number of elementary states is proportional to the surface area of the manifold, and the surface area of the manifold is the absolute value of the wave function. Therefore, the probability is proportional to the absolute square of the wave function. CONTENTS 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Subject .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 The importance of the subject ......................................................................................... -

1 Does Consciousness Really Collapse the Wave Function?

Does consciousness really collapse the wave function?: A possible objective biophysical resolution of the measurement problem Fred H. Thaheld* 99 Cable Circle #20 Folsom, Calif. 95630 USA Abstract An analysis has been performed of the theories and postulates advanced by von Neumann, London and Bauer, and Wigner, concerning the role that consciousness might play in the collapse of the wave function, which has become known as the measurement problem. This reveals that an error may have been made by them in the area of biology and its interface with quantum mechanics when they called for the reduction of any superposition states in the brain through the mind or consciousness. Many years later Wigner changed his mind to reflect a simpler and more realistic objective position, expanded upon by Shimony, which appears to offer a way to resolve this issue. The argument is therefore made that the wave function of any superposed photon state or states is always objectively changed within the complex architecture of the eye in a continuous linear process initially for most of the superposed photons, followed by a discontinuous nonlinear collapse process later for any remaining superposed photons, thereby guaranteeing that only final, measured information is presented to the brain, mind or consciousness. An experiment to be conducted in the near future may enable us to simultaneously resolve the measurement problem and also determine if the linear nature of quantum mechanics is violated by the perceptual process. Keywords: Consciousness; Euglena; Linear; Measurement problem; Nonlinear; Objective; Retina; Rhodopsin molecule; Subjective; Wave function collapse. * e-mail address: [email protected] 1 1. -

Quantum Trajectory Distribution for Weak Measurement of A

Quantum Trajectory Distribution for Weak Measurement of a Superconducting Qubit: Experiment meets Theory Parveen Kumar,1, ∗ Suman Kundu,2, † Madhavi Chand,2, ‡ R. Vijayaraghavan,2, § and Apoorva Patel1, ¶ 1Centre for High Energy Physics, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, India 2Department of Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science, Tata Institue of Fundamental Research, Mumbai 400005, India (Dated: April 11, 2018) Quantum measurements are described as instantaneous projections in textbooks. They can be stretched out in time using weak measurements, whereby one can observe the evolution of a quantum state as it heads towards one of the eigenstates of the measured operator. This evolution can be understood as a continuous nonlinear stochastic process, generating an ensemble of quantum trajectories, consisting of noisy fluctuations on top of geodesics that attract the quantum state towards the measured operator eigenstates. The rate of evolution is specific to each system-apparatus pair, and the Born rule constraint requires the magnitudes of the noise and the attraction to be precisely related. We experimentally observe the entire quantum trajectory distribution for weak measurements of a superconducting qubit in circuit QED architecture, quantify it, and demonstrate that it agrees very well with the predictions of a single-parameter white-noise stochastic process. This characterisation of quantum trajectories is a powerful clue to unraveling the dynamics of quantum measurement, beyond the conventional axiomatic quantum -

Collapse Theories

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PhilSci Archive Collapse Theories Peter J. Lewis The collapse postulate in quantum mechanics is problematic. In standard presentations of the theory, the state of a system prior to a measurement is a sum of terms, with one term representing each possible outcome of the measurement. According to the collapse postulate, a measurement precipitates a discontinuous jump to one of these terms; the others disappear. The reason this is problematic is that there are good reasons to think that measurement per se cannot initiate a new kind of physical process. This is the measurement problem, discussed in section 1 below. The problem here lies not with collapse, but with the appeal to measurement. That is, a theory that could underwrite the collapse process just described without ineliminable reference to measurement would constitute a solution to the measurement problem. This is the strategy pursued by dynamical (or spontaneous) collapse theories, which differ from standard presentations in that they replace the measurement-based collapse postulate with a dynamical mechanism formulated in terms of universal physical laws. Various dynamical collapse theories of quantum mechanics have been proposed; they are discussed in section 2. But dynamical collapse theories face a number of challenges. First, they make different empirical predictions from standard quantum mechanics, and hence are potentially empirically refutable. Of course, testability is a virtue, but since we have no empirical reason to think that systems ever undergo collapse, dynamical collapse theories are inherently empirically risky. Second, there are difficulties reconciling the dynamical collapse mechanism with special relativity. -

Quantum Theory: Exact Or Approximate?

Quantum Theory: Exact or Approximate? Stephen L. Adler§ Institute for Advanced Study, Einstein Drive, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA Angelo Bassi† Department of Theoretical Physics, University of Trieste, Strada Costiera 11, 34014 Trieste, Italy and Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Trieste Section, Via Valerio 2, 34127 Trieste, Italy Quantum mechanics has enjoyed a multitude of successes since its formulation in the early twentieth century. It has explained the structure and interactions of atoms, nuclei, and subnuclear particles, and has given rise to revolutionary new technologies. At the same time, it has generated puzzles that persist to this day. These puzzles are largely connected with the role that measurements play in quantum mechanics [1]. According to the standard quantum postulates, given the Hamiltonian, the wave function of quantum system evolves by Schr¨odinger’s equation in a predictable, de- terministic way. However, when a physical quantity, say z-axis spin, is “measured”, the outcome is not predictable in advance. If the wave function contains a superposition of components, such as spin up and spin down, which each have a definite spin value, weighted by coe±cients cup and cdown, then a probabilistic distribution of outcomes is found in re- peated experimental runs. Each repetition gives a definite outcome, either spin up or spin down, with the outcome probabilities given by the absolute value squared of the correspond- ing coe±cient in the initial wave function. This recipe is the famous Born rule. The puzzles posed by quantum theory are how to reconcile this probabilistic distribution of outcomes with the deterministic form of Schr¨odinger’s equation, and to understand precisely what constitutes a “measurement”. -

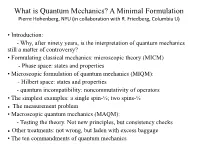

What Is Quantum Mechanics? a Minimal Formulation Pierre Hohenberg, NYU (In Collaboration with R

What is Quantum Mechanics? A Minimal Formulation Pierre Hohenberg, NYU (in collaboration with R. Friedberg, Columbia U) • Introduction: - Why, after ninety years, is the interpretation of quantum mechanics still a matter of controversy? • Formulating classical mechanics: microscopic theory (MICM) - Phase space: states and properties • Microscopic formulation of quantum mechanics (MIQM): - Hilbert space: states and properties - quantum incompatibility: noncommutativity of operators • The simplest examples: a single spin-½; two spins-½ ● The measurement problem • Macroscopic quantum mechanics (MAQM): - Testing the theory. Not new principles, but consistency checks ● Other treatments: not wrong, but laden with excess baggage • The ten commandments of quantum mechanics Foundations of Quantum Mechanics • I. What is quantum mechanics (QM)? How should one formulate the theory? • II. Testing the theory. Is QM the whole truth with respect to experimental consequences? • III. How should one interpret QM? - Justify the assumptions of the formulation in I - Consider possible assumptions and formulations of QM other than I - Implications of QM for philosophy, cognitive science, information theory,… • IV. What are the physical implications of the formulation in I? • In this talk I shall only be interested in I, which deals with foundations • II and IV are what physicists do. They are not foundations • III is interesting but not central to physics • Why is there no field of Foundations of Classical Mechanics? - We wish to model the formulation of QM on that of CM Formulating nonrelativistic classical mechanics (CM) • Consider a system S of N particles, each of which has three coordinates (xi ,yi ,zi) and three momenta (pxi ,pyi ,pzi) . • Classical mechanics represents this closed system by objects in a Euclidean phase space of 6N dimensions. -

Stochastic Quantum Potential Noise and Quantum Measurement

Chapter 7 Stochastic Quantum Potential Noise and Quantum Measurement Wei Wen Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.74253 Abstract Quantum measurement is the greatest problem in quantum theory. In fact, different views for the quantum measurement cause different schools of thought in quantum theory. The quandaries of quantum measurement are mainly concentrated in “stochastic measurement space”, “instantaneous measurement process” and “basis-preferred measurement space.” These quandaries are incompatible with classical physical laws and discussed many years but still unsolved. In this chapter, we introduce a new theory that provided a new scope to interpret the quantum measurement. This theory tells us the quandaries of quantum mea- surement are due to the nonlocal correlation and stochastic quantum potential noise. The quantum collapse had been completed by the noised world before we looked, and the moon is here independent of our observations. Keywords: quantum measurement, quantum collapse, quantum potential noise, Feynman path integral 1. Introduction Schrödinger cat was born from the thought experiment of Schrödinger in 1935. However, after more than 80 years, we still do not know whether it is dead or alive in its sealed box. According to the modern quantum mechanics, based on Copenhagen interpretation, the fate of this cat is entangled with the Geiger counter monitor in its box, and the cat is in a “mixed state”—both dead and alive—if we do not open the box to look at it. It is a miserable and mystical cat, which seems its fate depends on our look. -

Quantum Trajectories for Measurement of Entangled States

Quantum Trajectories for Measurement of Entangled States Apoorva Patel Centre for High Energy Physics, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 1 Feb 2018, ISNFQC18, SNBNCBS, Kolkata 1 Feb 2018, ISNFQC18, SNBNCBS, Kolkata A. Patel (CHEP, IISc) Quantum Trajectories for Entangled States / 22 Density Matrix The density matrix encodes complete information of a quantum system. It describes a ray in the Hilbert space. It is Hermitian and positive, with Tr(ρ)=1. It generalises the concept of probability distribution to quantum theory. 1 Feb 2018, ISNFQC18, SNBNCBS, Kolkata A. Patel (CHEP, IISc) Quantum Trajectories for Entangled States / 22 Density Matrix The density matrix encodes complete information of a quantum system. It describes a ray in the Hilbert space. It is Hermitian and positive, with Tr(ρ)=1. It generalises the concept of probability distribution to quantum theory. The real diagonal elements are the classical probabilities of observing various orthogonal eigenstates. The complex off-diagonal elements (coherences) describe quantum correlations among the orthogonal eigenstates. 1 Feb 2018, ISNFQC18, SNBNCBS, Kolkata A. Patel (CHEP, IISc) Quantum Trajectories for Entangled States / 22 Density Matrix The density matrix encodes complete information of a quantum system. It describes a ray in the Hilbert space. It is Hermitian and positive, with Tr(ρ)=1. It generalises the concept of probability distribution to quantum theory. The real diagonal elements are the classical probabilities of observing various orthogonal eigenstates. The complex off-diagonal elements (coherences) describe quantum correlations among the orthogonal eigenstates. For pure states, ρ2 = ρ and det(ρ)=0. Any power-series expandable function f (ρ) becomes a linear combination of ρ and I .