Samuel Zyman's Concerto for Cello and Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

Themenkatalog »Musik Verfolgter Und Exilierter Komponisten«

THEMENKATALOG »Musik verfolgter und exilierter Komponisten« 1. Alphabetisches Verzeichnis Babin, Victor Capriccio (1949) 12’30 3.3.3.3–4.3.3.1–timp–harp–strings 1908–1972 for orchestra Concerto No.2 (1956) 24’ 2(II=picc).2.2.2(II=dbn)–4.2.3.1–timp.perc(3)–strings for two pianos and orchestra Blech, Leo Das war ich 50’ 2S,A,T,Bar; 2(II=picc).2.corA.2.2–4.2.0.1–timp.perc–harp–strings 1871–1958 (That Was Me) (1902) Rural idyll in one act Libretto by Richard Batka after Johann Hutt (G) Strauß, Johann – Liebeswalzer 3’ 2(picc).1.2(bcl).1–3.2.0.0–timp.perc–harp–strings Blech, Leo / for coloratura soprano and orchestra Sandberg, Herbert Bloch, Ernest Concerto Symphonique (1947–48) 38’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(3):cyms/tam-t/BD/SD 1880–1959 for piano and orchestra –cel–strings String Quartet No.2 (1945) 35’ Suite Symphonique (1944) 20’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc:cyms/BD–strings Violin Concerto (1937–38) 35’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(2):cyms/tgl/BD/SD– harp–cel–strings Braunfels, Walter 3 Chinesische Gesänge op.19 (1914) 16’ 3(III=picc).2(II=corA).3.2–4.2.3.1–timp.perc–harp–cel–strings; 1882–1954 for high voice and orchestra reduced orchestraion by Axel Langmann: 1(=picc).1(=corA).1.1– Text: from Hans Bethge’s »Chinese Flute« (G) 2.1.1.0–timp.perc(1)–cel(=harmonium)–strings(2.2.2.2.1) 3 Goethe-Lieder op.29 (1916/17) 10’ for voice and piano Text: (G) 2 Lieder nach Hans Carossa op.44 (1932) 4’ for voice and piano Text: (G) Cello Concerto op.49 (c1933) 25’ 2.2(II=corA).2.2–4.2.0.0–timp–strings -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

11 7 Thseason

2016- 17 (117TH SEASON) Repertoire Bach Cantata No. 150, “Nach Dir, Herr, verlanget Feb. 23-25, 2017 mich”* Violin Concerto No. 1 Mar. 15-16, 2017 Bartók Bluebeard’s Castle Mar. 2-4, 2017 Bates Alternative Energy* Apr. 6-9, 2017 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 Feb. 2-4, 2017 Selections from The Creatures of Prometheus Apr. 6-9, 2017 Symphony No. 2 Dec. 8-10, 2016 Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) Mar. 10-12, 2017 Symphony No. 6 (“Pastoral”) Nov. 25-27, 2016 Violin Concerto Nov. 3-5, 2016 Berg Violin Concerto Mar. 10-12, 2017 Berlioz Le Corsaire Overture Oct. 7-8, 2016 Harold in Italy Jan. 26-27, 2017 Symphonie fantastique Sep. 22-24, 2016; Oct. 7-8, 2016 Bernstein Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs Mar. 30-Apr. 1, 2017 Symphony No. 1 (“Jeremiah”) May 3-6, 2017 Brahms Symphony No. 1 Oct. 27-29, 2016 Symphony No. 2 Nov. 3-5, 2016 Symphony No. 3 Feb. 17-19, 2017 Symphony No. 4 Feb. 23-25, 2017 Brahms/transcr. Selections from Eleven Choral Preludes Feb. 23-25, 2017 Glanert (world premiere of transcriptions) Britten War Requiem Mar. 23-25, 2017 Canteloube Selections from Songs of the Auvergne Jan. 12-14, 2017 Chabrier Joyeuse Marche** Jan. 12-14, 2017 – more – January 2016—All programs and artists subject to change. PAGE 2 The Philadelphia Orchestra 2016-17 Season Repertoire Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 Jan. 19-24, 2017 Piano Concerto No. 2 Sep. 22-24, 2016 Dutilleux Métaboles Oct. 27-29, 2016 Dvořák Symphony No. 8 Mar. 15-16, 2017 Symphony No. -

Playlist 12 - Wednesday, June 24Th, 2020

Legato in Times of Staccato Playlist 12 - Wednesday, June 24th, 2020 Curated by Music Director, Fouad Fakhouri William Dawson: Negro Folk Symphony William Dawson was a renowned African American composer, choir director, and professor who incorporated African American themes and melodies into his music. With the Negro Folk Symphony, Dawson aimed to “write a symphony in the Negro folk idiom, based on authentic folk music but in the same symphonic form used by the composers of the [European] romantic-nationalist school.” The work consists of three movements, each with its own programmatic subtitle. Dvorak: Serenade for Strings & Wind Dvořák composed his entire Serenade in E major for string orchestra in less than two weeks in May 1875. The piece is in five movements, and in the finale, the main theme from the first movement is quoted before the coda, effectively unifying the work. Overall, the piece is light and carefree, reflecting a happy and productive time in Dvořák’s life. The Serenade in D minor for wind instruments was also composed in just two weeks in January 1878. The winds play atop a foundation of cello and string bass, and like in the Serenade for Strings, the opening theme is quoted in the final movement to unify the piece. The work is Classical in form but Czech in character as Dvořák incorporated folk melodies and rhythms from his native Bohemian culture. The piece was dedicated to music critic Louis Ehlert who promoted Dvořák’s famous Slavonic Dances and helped to advance Dvořák’s musical career. Haydn: Cello Concerto No. 1 Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. -

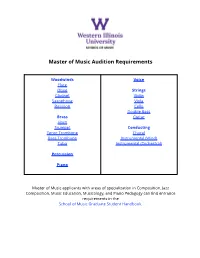

Audition Requirements

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. -

Cellist Zuill Bailey with Helen Kim and the KSU Symphony Orchestra

SCHOOL of MUSIC where PASSION is Zuill Bailey,heard Cello featuring Helen Kim, Violin Robert Henry, Piano KSU Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director and Conductor Wednesday, October 9, 2019 | 8:00 PM Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall musicKSU.com 1 heard Program LUKAS FOSS (1922-2009) CAPRICCIO MAX BRUCH (1838-1920) KOL NIDREI, OPUS 47 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) VARIATIONS ON A ROCOCO THEME, OPUS 33 Zuill Bailey, Cello Robert Henry, Piano –INTERMISSION– JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) CONCERTO FOR VIOLIN, CELLO, AND ORCHESTRA IN A MINOR, OPUS 102 I. ALLEGRO II. ANDANTE III. VIVACE NON TROPPO Zuill Bailey, Cello Helen Kim, Violin Kennesaw State University Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Conductor We welcome all guests with special needs and offer the following services: easy access, companion seating locations, accessible restrooms, and assisted listening devices. Please contact a patron services representative at 470-578-6650 to request services. 2 Kennesaw State University School of Music KSU Symphony Orchestra Personnel Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director & Conductor Personnel listed alphabetically to emphasize the importance of each part. Rotational seating is used in all woodwind, brass, and percussion sections. Flute Violin Cello Don Cofrancesco Melissa Ake^, Garrett Clay Lorin Green concertmaster Laci Divine Jayna Burton Colin Gregoire^, principal Oboe Abigail Carpenter Jair Griffin Emily Gunby Robert Cox^ Joseph Grunkmeyer, Robert Simon Mary Catherine Davis associate principal -

Franz Anton Hoffmeister’S Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in D Major a Scholarly Performance Edition

FRANZ ANTON HOFFMEISTER’S CONCERTO FOR VIOLONCELLO AND ORCHESTRA IN D MAJOR A SCHOLARLY PERFORMANCE EDITION by Sonja Kraus Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Emilio Colón, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Kristina Muxfeldt ______________________________________ Peter Stumpf ______________________________________ Mimi Zweig September 3, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Sonja Kraus iii Acknowledgements Completing this work would not have been possible without the continuous and dedicated support of many people. First and foremost, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my teacher and mentor Prof. Emilio Colón for his relentless support and his knowledgeable advice throughout my doctoral degree and the creation of this edition of the Hoffmeister Cello Concerto. The way he lives his life as a compassionate human being and dedicated musician inspired me to search for a topic that I am truly passionate about and led me to a life filled with purpose. I thank my other committee members Prof. Mimi Zweig and Prof. Peter Stumpf for their time and commitment throughout my studies. I could not have wished for a more positive and encouraging committee. I also thank Dr. Kristina Muxfeldt for being my music history advisor with an open ear for my questions and helpful comments throughout my time at Indiana University. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

UCLA Symphony Programs 2005-2019

UCLA SYMPHONY 2005 - 2019 November 30, 2005 Haydn Symphony No. 88 Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 102 Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, Op. 17 (Little Russian) Neal Stulberg, conductor and pianist Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * March 6, 2006 Stravinsky Suite No. 2 for Small Orchestra Mozart Clarinet Concerto, K. 622 Beethoven Symphony No. 1, Op. 21 Denexxel Domingo, clarinet Masters and doctoral students of Donald Neuen, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * June 9, 2006 Fauré Suite from Pélléas et Mélisande Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations, Op. 33 Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade, Op. 35 Isaac Melamed, cello John Carter and Daniel Cummings, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * November 29, 2006 Bernstein Overture to Candide Haydn Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Cello, Oboe and Bassoon, Op. 84 Puccini Preludio Sinfonico Liszt Les Préludes (Symphonic Poem No. 3) Mary Hofman, violin Isaac Melamed, cello Michelle An, oboe Amy Gillick, bassoon Daniel Cummings, Georgios Kountouris, Neal Stulberg, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * March 14, 2007 DANCE PARTY! Dvorak Slavonic Dance No. 7 in C major, Op. 72 Saint-Saens Danse Macabre, Op. 40 Falla Ritual Fire Dance from El Amor Brujo Piazzolla Tangazo Tchaikowsky Three Dances from Swan Lake Debussy Danse Sacrée et Danse Profane for harp and strings Glière Russian Sailors' Dance from The Red Poppy Copland Hoedown from Rodeo Sousa Hands Across the Sea Lindsay Strand-Polyak, violin Jacque Marshall, harp Masters and doctoral students of Donald Neuen, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * May 30, 2007 Mozart Symphony No. 35 (Haffner), K. 385 Ney Rosauro Concerto for Marimba and String Orchestra Moussorgsky/Ravel Pictures from an Exhibition Jamie Strowbridge, marimba Daniel Cummings and Georgios Kountouris, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA December 5, 2007 Mozart Overture to Don Giovanni Rheinberger Concerto for Organ No.