Monopsony 2013: Still Not Truly Symmetric Presented and Authored By: Jonathan M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economics of Competition in the U.S. Livestock Industry Clement E. Ward

Economics of Competition in the U.S. Livestock Industry Clement E. Ward, Professor Emeritus Department of Agricultural Economics Oklahoma State University January 2010 Paper Background and Objectives Questions of market structure changes, their causes, and impacts for pricing and competition have been focus areas for the author over his entire 35-year career (1974-2009). Pricing and competition are highly emotional issues to many and focusing on factual, objective economic analyses is critical. This paper is the author’s contribution to that effort. The objectives of this paper are to: (1) put meatpacking competition issues in historical perspective, (2) highlight market structure changes in meatpacking, (3) note some key lawsuits and court rulings that contribute to the historical perspective and regulatory environment, and (4) summarize the body of research related to concentration and competition issues. These were the same objectives I stated in a presentation made at a conference in December 2009, The Economics of Structural Change and Competition in the Food System, sponsored by the Farm Foundation and other professional agricultural economics organizations. The basis for my conference presentation and this paper is an article I published, “A Review of Causes for and Consequences of Economic Concentration in the U.S. Meatpacking Industry,” in an online journal, Current Agriculture, Food & Resource Issues in 2002, http://caes.usask.ca/cafri/search/archive/2002-ward3-1.pdf. This paper is an updated, modified version of the review article though the author cannot claim it is an exhaustive, comprehensive review of the relevant literature. Issue Background Nearly 20 years ago, the author ran across a statement which provides a perspective for the issues of concentration, consolidation, pricing, and competition in meatpacking. -

Application of Game Theory in Swedish Raw Material Market Rami Al-Halabi 2020-06-12

Application of game theory in Swedish raw material market Rami Al-Halabi 2020-06-12 Application of game theory in Swedish raw material market Investigating the pulpwood market Rami Al-Halabi Dokumenttyp – Självständigt arbete på grundnivå Huvudområde: Industriell organisation och ekonomi GR (C) Högskolepoäng: 15 HP Termin/år: VT2020 Handledare: Soleiman M. Limaei Examinator: Leif Olsson Kurskod/registreringsnummer: IG027G Utbildningsprogram: Civilingenjör, industriell ekonomi i Application of game theory in Swedish raw material market Rami Al-Halabi 2020-06-12 Sammanfattning Studien går ut på att analysera marknadsstrukturen för två industriföretag (Holmen och SCA) under antagandet att båda konkurrerar mot varandra genom att köpa rå material samt genom att sälja förädlade produkter. Produktmarknaden som undersöks är pappersmarknaden och antas vara koncentrerad. Rå materialmarknaden som undersöks är massavedmarknaden och antas karaktäriseras som en duopsony. Det visade sig att Holmen och SCA köper massaved från en stor mängd skogsägare. Varje företag skapar varje månad en prislista där de bestämmer bud priset för massaved. Priset varierar beroende på region. Både SCA och Holmen väljer mellan två strategiska beslut, antigen att buda högt pris eller lågt pris. Genom spelteori så visade det sig att båda industriföretagen använder mixade strategier då de i vissa tillfällen budar högt och i andra tillfällen budar lågt. Nash jämviktslägen för mixade strategier räknades ut matematiskt och analyserades genom dynamisk spelteori. Marknadskoncentrationen för pappersmarknaden undersöktes via Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI). Porters femkraftsmodell användes för att analysera industri konkurrensen. Resultatet visade att produktmarknaden är koncentrerad då HHI testerna gav höga indexvärden mellan 3100 och 1700. Det existerade dessutom ett Nash jämviktsläge för mixade strategier som gav SCA förväntad lönsamhet 1651 miljoner kronor och Holmen 1295 miljoner kronor. -

The FTC and the Law of Monopolization

George Mason University School of Law Law and Economics Research Papers Series Working Paper No. 00-34 2000 The FTC and the Law of Monopolization Timothy J. Muris As published in Antitrust Law Journal, Vol. 67, No. 3, 2000 This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://papers.ssrn.com/paper.taf?abstract_id=235403 The FTC and the Law of Monopolization by Timothy J. Muris Although Microsoft has attracted much more attention, recent developments at the FTC may have a greater impact on the law of monopolization. From recent pronouncements, the agency appears to believe that in monopolization cases government proof of anticompetitive effect is unnecessary. In one case, the Commission staff argued that defendants should not even be permitted to argue that its conduct lacks an anticompetitive impact. This article argues that the FTC's position is wrong on the law, on policy, and on the facts. Courts have traditionally required full analysis, including consideration of whether the practice in fact has an anticompetitive impact. Even with such analysis, the courts have condemned practices that in retrospect appear not to have been anticompetitive. Given our ignorance about the sources of a firm's success, monopolization cases must necessarily be wide-ranging in their search for whether the conduct at issue in fact created, enhanced, or preserved monopoly power, whether efficiency justifications explain such behavior, and all other relevant issues. THE FTC AND THE LAW OF MONOPOLIZATION Timothy J. Muris* I. INTRODUCTION Most government antitrust cases involve collaborative activity. Collabo- ration between competitors, whether aimed at sti¯ing some aspect of rivalry, such as ®xing prices, or ending competition entirely via merger, is the lifeblood of antitrust. -

Hearing on Oligopoly Markets, Note by the United States Submitted To

Unclassified DAF/COMP/WD(2015)45 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 12-Jun-2015 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________ English - Or. English DIRECTORATE FOR FINANCIAL AND ENTERPRISE AFFAIRS COMPETITION COMMITTEE Unclassified DAF/COMP/WD(2015)45 HEARING ON OLIGOPOLY MARKETS -- Note by the United States -- 16-18 June 2015 This document reproduces a written contribution from the United States submitted for Item 5 of the 123rd meeting of the OECD Competition Committee on 16-18 June 2015. More documents related to this discussion can be found at www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oligopoly-markets.htm. English English JT03378438 Complete document available on OLIS in its original format - This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of English Or. international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. DAF/COMP/WD(2015)45 UNITED STATES 1. Following on our submissions to previous OECD roundtables on oligopolies, notably the 1999 submission of the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission on Oligopoly (describing the theoretical and economic underpinnings of U.S. enforcement policy with regard to oligopolistic behavior),1 and the 2007 U.S. submission on facilitating practices in oligopolies,2 this submission focuses on certain approaches taken by the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) and the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division (“DOJ”) (together, “the Agencies”) to prevent the accumulation of unwarranted market power and address oligopoly issues. 2. Pursuant to U.S. -

Resale Price Maintenance in China – an Increasingly Economic Question

Resale Price Maintenance in China – an increasingly economic question Three recent decisions in China suggest that Resale Specifically, the Court was clear that since RPM was Price Maintenance cases will not be decided solely on a defined in the law as a “monopoly agreement”, it must be legal consideration but will also turn on the economic expected to have the impact of eliminating or restricting context of the agreements in question. competition in order to be found illegal. To determine whether the agreement had the impact of eliminating or Resale Price Maintenance (RPM) is a contractual restricting competition, the Court proposed four constituent commitment imposed by a supplier on its distributors not to economic questions: sell its product for less (or more) than a given price. It is very 1. Is competition in the relevant market “sufficient”? common in distribution contracts throughout the world, 2. Does the defendant have a “very strong” market especially in China because of the control that RPM position? provides over resale quality and the distribution chain. 3. What was the motive behind the RPM agreements? RPM is a particularly contentious area of competition law 4. What was the competitive effect of the RPM? since RPM clauses can be both beneficial and harmful to competition depending on the context in which they are implemented. For example, RPM may facilitate unlawful Specifically, the Court suggested that if competition in the collusion between suppliers by allowing them to control and market was sufficient then it would not have found the RPM monitor the final retail price. RPM may also be forced on agreement illegal. -

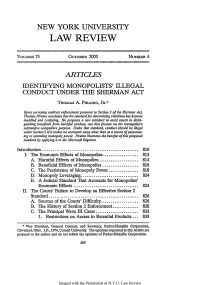

Identifying Monopolists' Illegal Conduct Under the Sherman Act

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 75 OCTOBER 2000 NUMBER 4 ARTICLES IDENTIFYING MONOPOLISTS' ILLEGAL CONDUCT UNDER THE SHERMAN ACT THOMAS A. Pmnn'io, JR.' Upon surveying antitrust enforcement pursuant to Section 2 of the Sherman Act, Thomas Pirainoconcludes that the standardfor determining violations has become muddled and confusing. He proposes a new standard to assist courts in distin- guishing beneficial from harmfid conduc; one that focuses on the monopolist's substantive competitive purpose. Under that standard, conduct should be illegal under Section 2 if it makes no economic sense other than as a means of perpetuat- ing or extending monopoly power. Pirainoillustrates the benefits of this proposed standard by applying it to the Microsoft litigation. Introduction .................................................... 810 I. The Economic Effects of Monopolies ................... 813 A. Harmful Effects of Monopolies ..................... 814 B. Beneficial Effects of Monopolies ................... 816 C. The Persistence of Monopoly Power ................ 818 D. Monopoly Leveraging ............................... 824 E. A Judicial Standard That Accounts for Monopolies' Economic Effects ................................... 824 II. The Courts' Failure to Develop an Effective Section 2 Standard ................................................ 826 A. Sources of the Courts' Difficulty .................... 826 B. The History of Section 2 Enforcement .............. 828 C. The Principal Wave III Cases ....................... 833 1. Restrictions on Access to Essential Products ... 833 * Vice President, General Counsel, and Secretary, Parker-Hannifin Corporation, Cleveland, Ohio. J.D., 1974, Cornell University. The opinions expressed in this Article are personal to the author and do not reflect the opinions of Parker-Hannifin Corporation. 809 Imaged with the Permission of N.Y.U. Law Review NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 75:809 2. Tying and Exclusive Dealing Arrangements ... -

A Comprehensive Economic and Legal Analysis of Tying Arrangements

A Comprehensive Economic and Legal Analysis of Tying Arrangements Guy Sagi* I. INTRODUCTION The law of tying arrangements as it stands does not correspond with modern economic analysis. Therefore, and because tying arrangements are so widely common, the law is expected to change and extensive aca- demic writing is currently attempting to guide its way. In tying arrangements, monopolistic firms coerce consumers to buy additional products or services beyond what they intended to purchase.1 This pressure can be applied because a consumer in a monopolistic mar- ket does not have the alternative to buy the product or service from a competing firm. In the absence of such choice, the monopolistic firm can allegedly force the additional purchase on the consumer at non-beneficial terms. The “tying product” is the one the consumer wants to buy, and the product the firm attaches to the tying product is termed the “tied prod- 2 uct.” * Lecturer, Netanya Academic College; Adjunct Lecturer, The Hebrew University School of Law; LL.B., The Hebrew University School of Law; LL.M. and J.S.D. Columbia University School of Law. 1. In a competitive market, consumers can choose to buy from firms that do not tie products, as opposed to ones that do. The tying firm, in such a case, would then lose out. At the same time, it is possible that in a competitive market, some products would still be offered together because it would be beneficial to both producers and consumers. 2. It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between the tying of two separate products and the sale of two components forming a single whole product. -

A Proposal to Enhance Antitrust Protection Against Labor Market Monopsony Roosevelt Institute Working Paper

A Proposal to Enhance Antitrust Protection Against Labor Market Monopsony Roosevelt Institute Working Paper Ioana Marinescu, University of Pennsylvania Eric A. Posner, University of Chicago1 December 21, 2018 1 We thank Daniel Small, Marshall Steinbaum, David Steinberg, and Nancy Walker and her staff, for helpful comments. 1 The United States has a labor monopsony problem. A labor monopsony exists when lack of competition in the labor market enables employers to suppress the wages of their workers. Labor monopsony harms the economy: the low wages force workers out of the workforce, suppressing economic growth. Labor monopsony harms workers, whose wages and employment opportunities are reduced. Because monopsonists can artificially restrict labor mobility, monopsony can block entry into markets, and harm companies who need to hire workers. The labor monopsony problem urgently calls for a solution. Legal tools are already in place to help combat monopsony. The antitrust laws prohibit employers from colluding to suppress wages, and from deliberately creating monopsonies through mergers and other anticompetitive actions.2 In recent years, the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department have awoken from their Rip Van Winkle labor- monopsony slumber, and brought antitrust cases against employers and issued guidance and warnings.3 But the antitrust laws have rarely been used by private litigants because of certain practical and doctrinal weaknesses. And when they have been used—whether by private litigants or by the government—they have been used against only the most obvious forms of anticompetitive conduct, like no-poaching agreements. There has been virtually no enforcement against abuses of monopsony power more generally. -

Market Failure Guide

Market failure guide A guide to categorising market failures for government policy development and evaluation industry.nsw.gov.au Published by NSW Department of Industry PUB17/509 Market failure guide—A guide to categorising market failures for government policy development and evaluation An external academic review of this guide was undertaken by prominent economists in November 2016 This guide is consistent with ‘NSW Treasury (2017) NSW Government Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis, TPP 17-03, Policy and Guidelines Paper’ First published December 2017 More information Program Evaluation Unit [email protected] www.industry.nsw.gov.au © State of New South Wales through Department of Industry, 2017. This publication is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material provided that the wording is reproduced exactly, the source is acknowledged, and the copyright, update address and disclaimer notice are retained. To copy, adapt, publish, distribute or commercialise any of this publication you will need to seek permission from the Department of Industry. Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing July 2017. However, because of advances in knowledge, users are reminded of the need to ensure that the information upon which they rely is up to date and to check the currency of the information with the appropriate officer of the Department of Industry or the user’s independent advisor. Market failure guide Contents Executive summary -

The United States Has a Market Concentration Problem Reviewing Concentration Estimates in Antitrust Markets, 2000-Present

THE UNITED STATES HAS A MARKET CONCENTRATION PROBLEM REVIEWING CONCENTRATION ESTIMATES IN ANTITRUST MARKETS, 2000-PRESENT ISSUE BRIEF BY ADIL ABDELA AND MARSHALL STEINBAUM1 | SEPTEMBER 2018 Since the 1970s, America’s antitrust policy regime has been weakening and market power has been on the rise. High market concentration—in which few firms compete in a given market—is one indicator of market power. From 1985 to 2017, the number of mergers completed annually rose from 2,308 to 15,361 (IMAA 2017). Recently, policymakers, academics, and journalists have questioned whether the ongoing merger wave, and lax antitrust enforcement more generally, is indeed contributing to rising concentration, and in turn, whether concentration really portends a market power crisis in the economy. In this issue brief, we review the estimates of market concentration that have been conducted in a number of industries since 2000 as part of merger retrospectives and other empirical investigations. The result of that survey is clear: market concentration in the U.S. economy is high, according to the thresholds adopted by the antitrust agencies themselves in the Horizontal Merger Guidelines. By way of background, recent studies of industry concentration conclude that it is both high and rising over time. For example, Grullon, Larkin, and Michaely conclude that concentration increased in 75% of industries from 1997 to 2012. In response to these and similar studies, the antitrust enforcement agencies recently declared that their findings are not relevant to the question of whether market concentration has increased because they study industrial sectors, not antitrust markets. Specifically, they wrote, “The U.S. -

Buyer Power: Is Monopsony the New Monopoly?

COVER STORIES Antitrust , Vol. 33, No. 2, Spring 2019. © 2019 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association. Buyer Power: Is Monopsony the New Monopoly? BY DEBBIE FEINSTEIN AND ALBERT TENG OR A NUMBER OF YEARS, exists—or only when it can also be shown to harm consumer commentators have debated whether the United welfare; (2) historical case law on monopsony; (3) recent States has a monopoly problem. But as part of the cases involving monopsony issues; and (4) counseling con - recent conversation over the direction of antitrust siderations for monopsony issues. It remains to be seen law and the continued appropriateness of the con - whether we will see significantly increased enforcement Fsumer welfare standard, the debate has turned to whether the against buyer-side agreements and mergers that affect buyer antitrust agencies are paying enough attention to monopsony power and whether such enforcement will be successful, but issues. 1 A concept that appears more in textbooks than in case what is clear is that the antitrust enforcement agencies will be law has suddenly become mainstream and practitioners exploring the depth and reach of these theories and clients should be aware of developments when they counsel clients must be prepared for investigations and enforcement actions on issues involving supply-side concerns. implicating these issues. This topic is not going anywhere any time soon. -

Investment Characteristics of Natural Monopoly Companies

Investment Characteristics of Natural Monopoly Companies Škapa Stanislav Abstract This paper explores the possibilities of investment by private investors in natural monopoly companies. The paper analyzes the broad issue of risk measurement with focus on downside risk measurement principle. The main scientific aim is to adopt a more sophisticated and theo- retically advanced statistical technique and apply them to the findings. The preferred method used for the estimation of selected characteristics and ratios was the robust statistical methods and a bootstrap method. Key words: natural monopoly, investor, investment, downside risk 1. INTRODUCTION Natural monopoly companies lead to a variety of economic performance problems: excessive prices, production inefficiencies, costly duplication of facilities, poor service quality and they have potentially undesirable distributional impacts. In the eyes of consumers, it is the high prices and poor service quality that they most probably perceive. However, the question that arises is: what brings the investment into the natural monopoly company to investors? 2. THEORETICAL SOLUTIONS 2.1 Natural monopoly Economists have been analyzing natural monopolies for more than 150 year. Sharkey (1982) provides an overview of the intellectual history of economic analysis of natural monopolies and he concludes that John Stuart Mill was the first to speak of natural monopolies in 1848. One of the main questions is how a natural monopoly should be defined. There are some characteristics which should help to understand what a natural monopoly mean. According Thomas Farrer (1902, referenced by Sharkey, 1982) a natural monopoly is associated with supply and demand of characteristics that include: the product or supplied service must be essential the products must be non-storable the supplier must have a favourable production location.