The Right to Farm Act in New Jersey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Costs for Beef Cattle, Cow-Calf Production

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AGRICULTURAL ISSUES CENTER UC DAVIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL AND RESOURCE ECONOMICS SAMPLE COSTS FOR BEEF CATTLE COW – CALF PRODUCTION 300 Head NORTHERN SACRAMENTO VALLEY 2017 Larry C. Forero UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Shasta County. Roger Ingram UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Placer and Nevada Counties. Glenn A. Nader UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Sutter/Yuba/Butte Counties. Donald Stewart Staff Research Associate, UC Agricultural Issues Center and Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Davis Daniel A. Sumner Director, UC Agricultural Issues Center, Costs and Returns Program, Professor, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Davis Beef Cattle Cow-Calf Operation Costs & Returns Study Sacramento Valley-2017 UCCE, UC-AIC, UCDAVIS-ARE 1 UC AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AGRICULTURAL ISSUES CENTER UC DAVIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL AND RESOURCE ECONOMICS SAMPLE COSTS FOR BEEF CATTLE COW-CALF PRODUCTION 300 Head Northern Sacramento Valley – 2017 STUDY CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 ASSUMPTIONS 3 Production Operations 3 Table A. Operations Calendar 4 Revenue 5 Table B. Monthly Cattle Inventory 6 Cash Overhead 6 Non-Cash Overhead 7 REFERENCES 9 Table 1. COSTS AND RETURNS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 10 Table 2. MONTHLY COSTS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 11 Table 3. RANGING ANALYSIS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 12 Table 4. EQUIPMENT, INVESTMENT AND BUSINESS OVERHEAD 13 INTRODUCTION The cattle industry in California has undergone dramatic changes in the last few decades. Ranchers have experienced increasing costs of production with a lack of corresponding increase in revenue. Issues such as international competition, and opportunities, new regulatory requirements, changing feed costs, changing consumer demand, economies of scale, and competing land uses all affect the economics of ranching. -

Change Climate: How Permaculture Revives Exhausted Soils for Food Production by Davis Buyondo

Change Climate: How Permaculture Revives Exhausted Soils For Food Production By Davis Buyondo Kyotera-Uganda Wilson Ssenyondo, a resident of Kabaale village, is among a few farmers in Kasasa sub-county, Kyotera district, Uganda, who have managed to restore their fatigued land for sustainable food production. He has managed to revive nearly two acres of land on which he grows banana, cassava, vegetables-egg plants, cabbages, sukuma wiki, beans, and groundnuts to list few. He renewed the land through permaculture, a form of farming where you recycle very element that creates life in the soil. You can simply add compost manure after soil loosening in addition to environment-friendly practices such as consistent mulching and carbon farming. Kabaale A is one of the communities in the district with a long history of being hard-hit by persistent dry spells. In such a situation crops wither and a few existing water sources dry up. At some point, the livestock farmers are forced to trek long distances in search for water and pasture. Others communities that share the same plight include Kabaale B, Nakagongo, Kyamyungu, Kabano A and Kabano B, Sabina, Bubango and Sanje villages. They are characterised by scorched and hardened soils, while others by sandy and stony terrain in addition to the high rate of deforestation. Considering that state, one does not expect to find much farming in these communities. But as you approach the villages, you cannot help but marvel at the lush green gardens containing different crops. But amid all these pressing challenges, some crop and livestock farmers have learnt how to adapt and look for ways for survival. -

Permaculture Design Plan Alderleaf Farm

PERMACULTURE DESIGN PLAN FOR ALDERLEAF FARM Alderleaf Farm 18715 299th Ave SE Monroe, WA 98272 Prepared by: Alderleaf Wilderness College www.WildernessCollege.com 360-793-8709 [email protected] January 19, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 What is Permaculture? 1 Vision for Alderleaf Farm 1 Site Description 2 History of the Alderleaf Property 3 Natural Features 4 SITE ELEMENTS: (Current Features, Future Plans, & Care) 5 Zone 0 5 Residences 5 Barn 6 Indoor Classroom & Office 6 Zone 1 7 Central Gardens & Chickens 7 Plaza Area 7 Greenhouses 8 Courtyard 8 Zone 2 9 Food Forest 9 Pasture 9 Rabbitry 10 Root Cellar 10 Zone 3 11 Farm Pond 11 Meadow & Native Food Forest 12 Small Amphibian Pond 13 Parking Area & Hedgerow 13 Well house 14 Zone 4 14 Forest Pond 14 Trail System & Tenting Sites 15 Outdoor Classroom 16 Flint-knapping Area 16 Zone 5 16 Primitive Camp 16 McCoy Creek 17 IMPLEMENTATION 17 CONCLUSION 18 RESOURCES 18 APPENDICES 19 List of Sensitive Natural Resources at Alderleaf 19 Invasive Species at Alderleaf 19 Master List of Species Found at Alderleaf 20 Maps 24 Frequently Asked Questions and Property Rules 26 Forest Stewardship Plan 29 Potential Future Micro-Businesses / Cottage Industries 29 Blank Pages for Input and Ideas 29 Introduction The permaculture plan for Alderleaf Farm is a guiding document that describes the vision of sustainability at Alderleaf. It describes the history, current features, future plans, care, implementation, and other key information that helps us understand and work together towards this vision of sustainable living. The plan provides clarity about each of the site elements, how they fit together, and what future plans exist. -

Farmer's Income

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Income in the United States, Its Amount and Distribution, 1909-1919, Volume II: Detailed Report Volume Author/Editor: Wesley Clair Mitchell, editor Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-001-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/mitc22-1 Publication Date: 1922 Chapter Title: Farmer's Income Chapter Author: Oswald W. Knauth Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c9420 Chapter pages in book: (p. 298 - 313) CHAPTER 24 FA1tiiERS' INCOME § 24a Introduction The information concerning farmers' income is fragmentary, butsuffi- cient in volume to justify the hope of attaining a fairly accurateestimate. Before this estimate is presented certain peculiarities of farmers'incomes and of the data concerning themmust be mentioned. (1) There is no other industry in which non-monetary income makesso large a proportion of the total as in farming. Besides the rental valuesof the farm homes occupied by owners, we must count in the value ofthe food and fuel which farmers producefor their own consumption. (2) Usually the farmer is not onlya producer but also a land speculator. Indeed, it is rather.upon the increasein the value of his land than sale of his produce that the upon the farmer rests whatever hopehe cherishes of growing rich. How large the growth in landvalues is appears from the Censuses of 1900 and 1910, which report an increase inthe value of farm lands of $15 billion in addition to an increase of $5 billion in thevalue of farm buildings, machinery, and live stock.'Fifteen billions for all farms in ten years means an average annual increase in thevalue of each farm amounting to $323.In the decade covered byour estimates the average increase must have been muchlarger, because of thegreat rise in the prices of farm lands which culminated in 1920.? Whena farmer realizes a profit by selling his land atan enhanced price, that profit constitutes him as an individual. -

Guide to Raising Dairy Sheep

A3896-01 N G A N I M S I A L A I S R — Guide to raising N F O dairy sheep I O T C C Yves Berger, Claire Mikolayunas, and David Thomas U S D U O N P R O hile the United States has a long Before beginning a dairy sheep enterprise, history of producing sheep for producers should review the following Wmeat and wool, the dairy sheep fact sheet, designed to answer many of industry is relatively new to this country. the questions they will have, to determine In Wisconsin, dairy sheep flocks weren’t if raising dairy sheep is an appropriate Livestock team introduced until the late 1980s. This enterprise for their personal and farm industry remains a small but growing goals. segment of overall domestic sheep For more information contact: production: by 2009, the number of farms in North America reached 150, Dairy sheep breeds Claire Mikolayunas Just as there are cattle breeds that have with the majority located in Wisconsin, Dairy Sheep Initiative been selected for high milk production, the northeastern U.S., and southeastern Dairy Business Innovation Center there are sheep breeds tailored to Canada. Madison, WI commercial milk production: 608-332-2889 Consumers are showing a growing interest n East Friesian (Germany) [email protected] in sheep’s milk cheese. In 2007, the U.S. n Lacaune (France) David L. Thomas imported over 73 million pounds of sheep Professor of Animal Sciences milk cheese, such as Roquefort (France), n Sarda (Italy) Manchego (Spain), and Pecorino Romano University of Wisconsin-Madison n Chios (Greece) Madison, Wisconsin (Italy), which is almost twice the 37 million n British Milksheep (U.K.) 608-263-4306 pounds that was imported in 1985. -

The Farmer and Minnesota History

THE FARMER AND MINNESOTA HISTORY' We stand at what the Indian called " Standing Rock." Rock is history. The nature of the earth before the coming of man he interprets as best he can from the records in rock. Rock in its varied formations is abundantly useful to man. It is of particular interest to the farmer as the soil he tills is com posed largely of finely divided rock. The great variation of soil is determined mainly by the rock from which it is derived. How fascinating that the student of the soil after reading the records of the rock finds by experi ment in certain cases that by adding rock to rock — as lime stone, nitrates, phosphate, or potassium to the soil — it may be made more responsive to the needs of man. Rock history then is quite engaging to the farmer, and if to him, to others also. Soil determines or may modify civilization. The role played by soil has determined the development of agriculture in the older countries of the world — Asia Minor, Spain, China, Greece, and Rome.^ Who would not say that the soil has been a major factor in the development of America? Hennepin made a pointed inference when, in the latter part of the sixteenth century, after exploring what he called " a vast country in America," he wrote: I have had an Opportunity to penetrate farther into that Unknown Continent than any before me; wherein I have discover'd New Countries, which may be justly call'd the Delights of that New World. They are larger than Europe, water'd with an infinite number of fine Rivers, the Course of one of which is above 800 ^ This paper was prepared for presentation at Castle Rock on June 16, 1926, as a feature of the fifth annual " historic tour" of the Minnesota Historical Society. -

Practical Farmers of Iowa Is Hiring a Livestock Coordinator

Practical Farmers of Iowa is Hiring a Livestock Coordinator Practical Farmers of Iowa is seeking an outgoing and dedicated professional to join our staff as livestock coordinator. For over 35 years, PFI has equipped farmers to build resilient farms and communities through farmer- to-farmer knowledge-sharing, on-farm research and strategic partnerships. This full-time position will work with PFI staff, farmers and members to design, coordinate and execute farmer-led educational events, and will serve as a relationship- and network-builder for livestock farmers in the Practical Farmers community. The livestock coordinator will work closely with many types of farmers, enterprises and systems, including conventional and organic, medium- and small-scale livestock farmers and graziers comprising beef, swine, sheep, goat, poultry and dairy farmers. The livestock coordinator will join a dynamic, innovative team at Practical Farmers of Iowa whose passion for Iowa’s ecosystems, communities, farms and rural livelihoods is mobilized though farmer-led work, servant leadership and grassroots movements for lasting landscape change. The livestock coordinator need not be an expert in livestock production and management, but must have experience with diversified livestock farmers, pasture-based systems and an ability to understand, discern and respond to their evolving needs and interests. Practical Farmers offers a flexible, fast-paced work environment with opportunities for independent initiative and professional development. Duties: • Plan, organize -

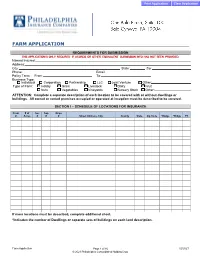

Farm Application

FARM APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS FOR SUBMISSION THIS APPLICATION IS ONLY REQUIRED IF ACORDS OR OTHER EQUIVALENT SUBMISSION INFO HAS NOT BEEN PROVIDED. Named Insured: Address: City: State: Zip: Phone: Email: Policy Term: From: To: Business Type: Individual Corporation Partnership LLC Joint Venture Other: Type of Farm: Hobby Grain Livestock Dairy Fruit Nuts Vegetables Vineyards Nursery Stock Other: ATTENTION: Complete a separate description of each location to be covered with or without dwellings or buildings. All owned or rented premises occupied or operated at inception must be described to be covered. SECTION I – SCHEDULE OF LOCATIONS FOR INSURANCE Prem # of Sec Twp Rnge # Acres # # # Street Address, City County State Zip Code *Dwlgs *Bldgs PC If more locations must be described, complete additional sheet. *Indicates the number of Dwellings or separate sets of buildings on each land description. Farm Application Page 1 of 16 02/2021 © 2021 Philadelphia Consolidated Holding Corp. SECTION II – ADDITIONAL INTEREST 1. Please check as applicable: Mortgagee Loss Payee Contract Holder Additional Insured Lessor of Leased Equipment 2. Name: Loan Number: 3. Address: City: State: Zip: 4. Applies to: 5. Please check as applicable: Mortgagee Loss Payee Contract Holder Additional Insured Lessor of Leased Equipment 6. Name: Loan Number: 7. Address: City: State: Zip: 8. Applies to: If additional lienholders needed, attach separate sheet. SECTION III – FARM LIABILITY COVERAGES LIMITS OF LIABILITY H. Bodily Injury & Property Damage $ I. Personal & Advertising Injury $ Basic Farm Liability Blanketed Acres Yes No Total Number of Acres Additional dwellings on insured farm location.owned by named insured or spouse Additional dwellings off insured farm location, owned by named insured or spouse and rented to others, but at least partly owner-occupied Additional dwellings off insured farm location, owned by named insured or spouse and rented to others with no part owner-occupied Additional dwellings on or off insured location, owned by a resident member of named insured’s household J. -

Quantity of Livestock for Farm Deferral

Quantity of Livestock for Farm Deferral Factors Include: How many animals do you need to qualify for farm deferral? ▪ Soil Quality ▪ Use of Irrigation There is no simple answer to this question. Whether ▪ Time of Year you are trying to qualify for the farm deferral program ▪ Topography and Slope or simply remain in compliance, there are many ▪ Type and Size of Livestock underlying factors. ▪ Wooded Vs. Open Each property is unique in how many animals per acre it can support. The following general guidelines have been developed. This is a suggested number of animals, because it varies on weight, size, breed and sex of animal. Approximate Requirements for Adult Animals on Dry Pasture: This is a rough estimate of how many pounds per acre. Horses (Excluding personal/pleasure) 1 head per 2 acres Typically, 100-800 Cattle – 1 to 2 head per 2 acres pounds minimum on Llamas – 1 to 2 head per acre dry and 500-1000 on irrigated pasture. Sheep – 2 to 4 head per acre Goats – 3 to 5 head per acre Range Chickens – 100-300 per acre size Important to Remember: The portion of the property in farm deferral must be used fully and exclusively for a compliant farming practice with the primary intent of making a profit. It must contain quality forage and be free of invasive weeds and brush. The forage must be grazed by sufficient number of livestock to keep it eaten down during the growing season. If pasture has adequate livestock but is full of blackberry briars, noxious weeds like scotch broom and tansy ragwort, or is full of debris like scrap metal, it will NOT qualify for farm use. -

Scaling Sustainable Agriculture: the Farmer-To-Farmer Agroecology Movement in Cuba

Scaling sustainable agriculture The Farmer-to-Farmer Agroecology movement in Cuba This is the inspiring story of the Farmer-to-Farmer Agroecology Movement (MACAC) which has spread across Cuba and inspired over 200,000 farmers to take up agroecological farming practices. The case study shows that it possible for a social movement to take sustainable agroecological farming systems to scale. Their experience counters the logic of conventional top-down approaches of agricultural extension and shows that locally specific solutions developed and disseminated by farmers themselves can provide significant and sustainable benefits for food production, rural livelihoods and environmental restoration. The experience provides valuable insights about how agroecology can help improve farmers’ wellbeing while simultaneously restoring the ecological health of the environment on which people’s livelihoods depend, increasing climate resilience and reducing carbon emissions from agriculture. www.oxfam.org OXFAM CASE STUDY – JANUARY 2021 OXFAM’S INSPIRING BETTER FUTURES CASE STUDY SERIES The case study forms part of Oxfam’s Inspiring Better Futures series which aims to inspire inform, and catalyse action to build a fairer, more caring and environmentally sustainable future. The 18 cases show how people are already successfully creating better futures, benefitting millions of people, even against the odds in some of the world’s toughest contexts in lower-income countries. The cases, which range from inspirational to strongly aspirational have all achieved impact at scale by successfully addressing underlying structural causes of the converging economic, climate and gender crises. In a COVID-changed world they provide compelling examples of how to achieve a just and green recovery and build resilience to future shocks. -

Strengthening Farm-Agribusiness Linkages in Africa Iii

$*6) 2FFDVLRQDO 3DSHU 6WUHQJWKHQLQJ IDUPDJULEXVLQHVV OLQNDJHVLQ$IULFD 6XPPDU\UHVXOWVRIILYH FRXQWU\VWXGLHVLQ*KDQD 1LJHULD.HQ\D8JDQGDDQG 6RXWK$IULFD $*6) 2FFDVLRQDO 3DSHU 6WUHQJWKHQLQJ IDUPDJULEXVLQHVV OLQNDJHVLQ$IULFD 6XPPDU\UHVXOWVRIILYH FRXQWU\VWXGLHVLQ*KDQD 1LJHULD.HQ\D8JDQGDDQG 6RXWK$IULFD E\ $QJHOD'DQQVRQ$FFUD*KDQD &KXPD(]HGLQPD,EDGDQ1LJHULD 7RP5HXEHQ:DPEXD1MXUX.HQ\D %HUQDUG%DVKDVKD0DNHUHUH8QLYHUVLW\8JDQGD -RKDQQ.LUVWHQDQG.XUW6DWRULXV3UHWRULD6RXWK$IULFD (GLWHGE\$OH[DQGUD5RWWJHU $JULFXOWXUDO0DQDJHPHQW0DUNHWLQJDQG)LQDQFH6HUYLFH $*6) $JULFXOWXUDO6XSSRUW6\VWHPV'LYLVLRQ )22'$1'$*5,&8/785(25*$1,=$7,212)7+(81,7('1$7,216 5RPH 5IFEFTJHOBUJPOTFNQMPZFEBOEUIFQSFTFOUBUJPOPGNBUFSJBM JOUIJTJOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUEPOPUJNQMZUIFFYQSFTTJPOPGBOZ PQJOJPOXIBUTPFWFSPOUIFQBSUPGUIF'PPEBOE"HSJDVMUVSF 0SHBOJ[BUJPO PG UIF 6OJUFE /BUJPOT DPODFSOJOH UIF MFHBM PS EFWFMPQNFOUTUBUVTPGBOZDPVOUSZ UFSSJUPSZ DJUZPSBSFBPSPG JUTBVUIPSJUJFT PSDPODFSOJOHUIFEFMJNJUBUJPOPGJUTGSPOUJFSTPS CPVOEBSJFT "MM SJHIUT SFTFSWFE 3FQSPEVDUJPO BOE EJTTFNJOBUJPO PG NBUFSJBM JO UIJT JOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUGPSFEVDBUJPOBMPSPUIFSOPODPNNFSDJBMQVSQPTFTBSF BVUIPSJ[FEXJUIPVUBOZQSJPSXSJUUFOQFSNJTTJPOGSPNUIFDPQZSJHIUIPMEFST QSPWJEFEUIFTPVSDFJTGVMMZBDLOPXMFEHFE3FQSPEVDUJPOPGNBUFSJBMJOUIJT JOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUGPSSFTBMFPSPUIFSDPNNFSDJBMQVSQPTFTJTQSPIJCJUFE XJUIPVUXSJUUFOQFSNJTTJPOPGUIFDPQZSJHIUIPMEFST"QQMJDBUJPOTGPSTVDI QFSNJTTJPOTIPVMECFBEESFTTFEUPUIF$IJFG 1VCMJTIJOH.BOBHFNFOU4FSWJDF *OGPSNBUJPO%JWJTJPO '"0 7JBMFEFMMF5FSNFEJ$BSBDBMMB 3PNF *UBMZ PSCZFNBJMUPDPQZSJHIU!GBPPSH ª'"0 Strengthening farm-agribusiness -

Introduction to Whole Farm Planning • Marketing • Whole Farm Business Management and Planning • Land Acquisition and Tenure • Sustainable Farming Practices

www.vabeginningfarmer.org Virginia Whole Farm Planning: An Educational Program for Farm Startup and Development Sustainable Farming Practices: Animal Husbandry The purpose of the Sustainable Farming Practices: Animal Husbandry module is to help beginning farmers and ranchers in Virginia learn the basic fundamental production practices and concepts necessary to make informed decisions for whole farm planning. This is one of five modules designed to guide you in developing the whole farm plan by focusing on the following areas: • Introduction to Whole Farm Planning • Marketing • Whole Farm Business Management and Planning • Land Acquisition and Tenure • Sustainable Farming Practices Each module is organized at the introductory to intermediate stage of farming knowledge and experience. At the end of each module, additional resources and Virginia service provider contact information are available to help continue the farm planning process. Authors: Cindy Wood Virginia Tech, Department of Animal and Poultry Science Cindi Shelley Virginia Cooperative Extension programs and employment are open to all, SUNY Cobleskill, Department of Animal and regardless of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. An equal Plant Sciences opportunity/affirmative action employer. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Virginia State University, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating. Edwin J. Jones, Director, Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg; Jewel E. Hairston, Administrator, 1890 Extension Program, Virginia State, Petersburg. Funding for this curriculum is sponsored by the Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program (BFRDP) of the USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Award # 2010-49400.