ETHJ Vol-35 No-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayor Calls for Appointed School Board

THE Your want ad The Zip Code is easy to place * for Lihden is -Phone 636-7700 which became a Suburban Publblishinj C6rm newspoper on July 2, 1964 07036 An Official Newspopeir Linden PdWefcW la ck Tt>i»«4»y by ln W tw C>»y. VOL. 14-NO. 31 LINDEN. N.J., THURSDAY. JANUARY 12,1978 Subscription 8 *t* *» SOY to n y 25c por co p y l i t Mertfc j»ee4 Ltndmm, N. JL 07034 Second CI*m eottae* Pttd at Lineon, N J Mayor calls for appointed school board Burke issues show-cause on racial plan Suggests change in Current Dates, times are fixed poiicy not message for council sessions Campaign starting new football coach The City Council, during its July 17. 7:30 p.m . conference: July W »nil— lelN telW M IiirtiH rtsrhtog pnlHia itlM eW p organization meeting on Jan. 4. passed' 18. 7:30 p.m , conference, 8 p m . for referendum proper a resolution fixing the times and dates regular k M u t m w NN| m p ie. jtwNh| to TWb m Ltmg. ssotofato Bv RICH ARD LI ONGO of conference and regular meetings Aug. 14. 7:30 p m , conference; Aug ■ totow tol to scbssfa. Mayor John T Gregorio has called during 1978 15. 7:30 pm . conference, 8 p m . I V pwidw to far to* 1STS-TS k M y**r. I V m w twdi *fl r^toct 'Racial balance' for a return to an appointed Board of stops* his taschtoM csstofag pasts at toe The dates are as follows: regular Education to replace the current Jan 3, 7:30 p.m., conference Sept 18. -

Ranching Catalogue

Catalogue Ten –Part Four THE RANCHING CATALOGUE VOLUME TWO D-G Dorothy Sloan – Rare Books box 4825 ◆ austin, texas 78765-4825 Dorothy Sloan-Rare Books, Inc. Box 4825, Austin, Texas 78765-4825 Phone: (512) 477-8442 Fax: (512) 477-8602 Email: [email protected] www.sloanrarebooks.com All items are guaranteed to be in the described condition, authentic, and of clear title, and may be returned within two weeks for any reason. Purchases are shipped at custom- er’s expense. New customers are asked to provide payment with order, or to supply appropriate references. Institutions may receive deferred billing upon request. Residents of Texas will be charged appropriate state sales tax. Texas dealers must have a tax certificate on file. Catalogue edited by Dorothy Sloan and Jasmine Star Catalogue preparation assisted by Christine Gilbert, Manola de la Madrid (of the Autry Museum of Western Heritage), Peter L. Oliver, Aaron Russell, Anthony V. Sloan, Jason Star, Skye Thomsen & many others Typesetting by Aaron Russell Offset lithography by David Holman at Wind River Press Letterpress cover and book design by Bradley Hutchinson at Digital Letterpress Photography by Peter Oliver and Third Eye Photography INTRODUCTION here is a general belief that trail driving of cattle over long distances to market had its Tstart in Texas of post-Civil War days, when Tejanos were long on longhorns and short on cash, except for the worthless Confederate article. Like so many well-entrenched, traditional as- sumptions, this one is unwarranted. J. Evetts Haley, in editing one of the extremely rare accounts of the cattle drives to Califor- nia which preceded the Texas-to-Kansas experiment by a decade and a half, slapped the blame for this misunderstanding squarely on the writings of Emerson Hough. -

“Hauntology Man”

HAUNTOLOGY MAN Adam Michael Wright Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2018 APPROVED: James M. Martin, Major Professor Ben Levin, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Committee Member Eugene Martin, Chair of the Department of Media Arts David Holdeman, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Wright, Adam Michael. “Hauntology Man.” Master of Fine Arts (Documentary Production and Studies), May 2018, 78 pp., works cited, 52 titles. Hauntology Man, a 48-minute documentary, follows former UNT professor, Dr. Shaun Treat, as he leads a walking ghost tour of downtown Denton, Texas. As the expedition moves from storefront to storefront, each stop elicits a new tale. But, as Dr. Treat points out, the uncertainties of history are the real ghosts. That is, rather than simply presenting a “haunted history” of Denton, it’s more accurate to say this movie’s center resides at the precipice of a “haunting history.” Not all ghost stories need spectres. Sometimes not knowing is ghost enough. Copyright 2018 By Adam Michael Wright ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. PROSPECTUS ..................................................................... 1 Overview..................................................................................... 1 Treatment ................................................................................... 5 Outline ...................................................................................... 15 Concerns -

Quarterlyaw I Fall 2013 Volume 62 Number 4 AW I Quarterly About the Cover

QuarterlyAW I Fall 2013 Volume 62 Number 4 AW I Quarterly About the Cover A goat stands next to a school bus at Prodigal Farm in Rougemont, North Carolina. Prodigal Farm is Animal Welfare Approved (AWA)—meaning the animals are raised in accordance with FOUNDER Christine Stevens the most rigorous and progressive farm animal care standards in the world. Finding an animal on pasture at an AWA farm isn’t surprising—continuous pasture access is required whether DIRECTORS Cynthia Wilson, Chair the animals are goats, cows, pigs, chickens or other. Finding a school bus in the field, however, John W. Boyd, Jr. is a little unique. The bus is the clever solution by owners Dave Crabbe and Kathryn Spann to Barbara K. Buchanan the problem of providing the goats with mobile shelter. When the goats are moved to a new Charles M. Jabbour paddock to take advantage of fresh browse, the shelter follows along. A closer look at Prodigal Mary Lee Jensvold, Ph.D. Cathy Liss Farm, as well as its owners, goats, and buses can be found on page 6. Michele Walter Photo by Mike Suarez OFFICERS Cathy Liss, President Cynthia Wilson, Vice President Charles M. Jabbour, CPA, Treasurer Barbara K. Buchanan, Secretary SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Anniversaries that Are Cause Gerard Bertrand, Ph.D. Roger Fouts, Ph.D. for Consternation Roger Payne, Ph.D. Samuel Peacock, M.D. HUMANITARIANS have been waiting for more than a year for action on Viktor Reinhardt, D.V.M., Ph.D. Hope Ryden two egregious situations—both reported previously in the Winter 2013 AWI Robert Schmidt, Ph.D. -

Wednesday Flurries MICHIGAN in War

Wednesday Flurries MICHIGAN In war . likely with a high of 33 degrees. Low tonight: 15 de . whichever side may call STATE grees. Thursday's outlook is itself the victor, there are no partly cloudy and cool. winners, but ail are losers. UNIVERSITY Neville Chamberlain East Lansing, Michigan March 6,1968 lkc Vol. 60 Number 141 ALONE ON N .H .BA LLO T Negro shooting N i x o n v o w s q u i c k e n d brings tension to O m a h a to Viet war under G O P OMAHA, Neb. (AP)-Tension mounted HAMPTON. N.H. (API-Former Vice energetic campaign days, a five-town " I do not suggest withdrawal from steadily in Omaha Tuesday following the President Richard M. Nixon, sole Re sprint, urging the voters to turn out Vietnam. early morning fatal shooting of a Negro publican campaigner for the nation's for the primary on March 12. "I am saying to you it is possible teen-ager during a series of disorders that opening presidential primary, pledged anew Gov. Romney, once his chief rival, that if we mobilize our economic and began when Former Gov. George Wal Tuesday that a GOP administration would has withdrawn as a candidate, although political and diplomatic leadership, it lace of Alabama came to town to launch end the war in Vietnam. his name will still be listed on the •can be ended." he said. "The failure his third party presidential campaign. Alone as a major on-the-ballot GOP New Hampshire ballot. There is a in Vietnam is not the failure of our Ernest Chambers, militant Omaha candidate. -

Bonnie and Clyde: the Making of a Legend by Karen Blumenthal, 2018, Viking Books for Young Readers

Discussion and Activity Guide Bonnie and Clyde: The Making of a Legend by Karen Blumenthal, 2018, Viking Books for Young Readers BOOK SYNOPSIS “Karen Blumenthal’s breathtaking true tale of love, crime, and murder traces Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow’s wild path from dirt-poor Dallas teens to their astonishingly violent end and the complicated legacy that survives them both. This is an impeccably researched, captivating portrait of an infamous couple, the unforgivable choices they made, and their complicated legacy.” (publisher’s description from the book jacket) ABOUT KAREN BLUMENTHAL “Ole Golly told me if I was going to be a writer I better write down everything … so I’m a spy that writes down everything.” —Harriet the Spy, Louise Fitzhugh Like Harriet M. Welsch, the title character in Harriet the Spy, award-winning author Karen Blumenthal is an observer of the world around her. In fact, she credits the reading of Harriet the Spy as a child with providing her the impetus to capture what was happening in the world around her and become a writer herself. Like most authors, Blumenthal was first a reader and an observer. She frequented the public library as a child and devoured books by Louise Fitzhugh and Beverly Cleary. She says as a child she was a “nerdy obnoxious kid with glasses” who became a “nerdy obnoxious kid with contacts” as a teen. She also loved sports and her hometown Dallas sports teams as a kid and, consequently, read books by sports writer, Matt Christopher, who inspired her to want to be a sports writer when she grew up. -

Book Reviews

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 38 Issue 2 Article 12 10-2000 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (2000) "Book Reviews," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 38 : Iss. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol38/iss2/12 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 78 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION Tales ofthe Sabine Borderlands: Early Louisiana and Texas Fiction, Theodore Pavie. Edited with an introduction and notes by Be~le Black Klier (Texas A&M University Press, 4354 TAMUS, College Station, TX 77843-4354) 1998. Contents. Tllus. Acknowledgments. "The Myth of the Sabine." Index. P.IIO. $25.95. Hardcover. Theodore Pavie was eighteen years old and a full-blown, wide-eyed Romantic in 1829 when he sailed from France to Louisiana to visit his uncle on a pJantatlon near Natchitoches. While there, Pavie was adventurous enough to explore the wilderness road between Natchitoches and Nacogdoches, and he was completely entranced by the people of the frontier wilderness on both sides of the Sabine River. He absorbed the whole Borderland panorama, ran the experience through the filter of The Romantic Age, and produced a semi fictional travel book and several short stories. The short stories. these Tales of the Sabine Borderlands. -

HERSTORY Dartmouth ‘61

HERSTORY Dartmouth ‘61 Edited by Nyla Arslanian June 2011 Introduction Table of Contents Thank you all for your generosity in sharing your stories My first reunion was the 10th and I fell in love. The beautiful cam- pus, the heritage and tradition was awesome to this California girl, but it was the people I met that year and at each successive reunion, who were Nyla Arslanian so wonderfully generous with their friendship. As Oscar's wife, I was in- Carol T. Baum stantly accepted and year after year, reunions, mini-reunions, we lived our Gene Below Bland lives apart but also “together” as we moved through our life's passages— Ruth Zimmerman Bleyler trials, tribulations and triumphs. Each reunion providing a touch stone as Marjorie (Marge) B. Boss we shared our stories and realized we were part of something special—the Betty Castor bridge or leading edge of the boom to follow. We embraced both swing DeVona (Dee) McLaughlin Cox * and rock ’n roll and were better for it. Kathy Hanegan Dayton * Friendships that began over 50 years ago have been sustained and new Jean LaRue DeHaven friendships that developed over the last 50 years continue to enrich our Kathy Eicke lives. Sara Evans Through the “Passages” tradition that began years ago, the Men of '61 Kathleen (Kathy) Newton Foote have included the women in the discussion, wisely listening and respect- Ricky Forester ing our views and opinions. Bonnie Gartner It is in that spirit that this collection of stories is dedicated to the Madge Ginn Women of Dartmouth '61 and their mates. -

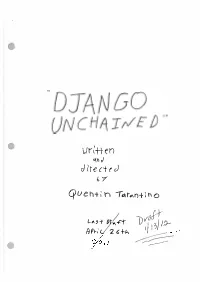

Django Unchained (2012) Screenplay

' \Jl't-H- en �'1 J drtecitJ b/ qu eh+; h -r�r... n+ l ho ,r Lo\5-t- () .<..+-t vof I 3/ I;)-- ftp�;L 2 t 1-h 1) \ I ' =------- I EXT - COUNTRYSIDE - BROILING HOT DAY As the film's OPENING CREDIT SEQUENCE plays, complete with its own SPAGHETTI WESTERN THEME SONG, we see SEVEN shirtless and shoeless BLACK MALE SLAVES connected together with LEG IRONS, being run, by TWO WHITE MALE HILLBILLIES on HORSEBACK. The location is somewhere in Texas. The Black Men (ROY, BIG SID, BENJAMIN, DJANGO, PUDGY RALPH, FRANKLYN, and BLUEBERRY) are slaves just recently purchased at The Greenville Slave Auction in Greenville Mississippi. The White Hillbillies are two Slave Traders called, The SPECK BROTHERS (ACE and DICKY). One of the seven slaves is our hero DJANGO.... he's fourth in the leg iron line. We may or may not notice a tiny small "r" burned into his cheek ("r" for runaway), but we can't help but notice his back which has been SLASHED TO RIBBONS by Bull Whip Beatings. As the operatic Opening Theme Song plays, we see a MONTAGE of misery and pain, as Django and the Other Men are walked through blistering sun, pounding rain, and moved along by the end of a whip. Bare feet step on hard rock, and slosh through mud puddles. Leg Irons take the skin off ankles. DJANGO Walking in Leg Irons with his six Other Companions, walking across the blistering Texas panhandle .... remembering... thinking ... hating .... THE OPENING CREDIT SEQUENCE end. EXT - WOODS - NIGHT It's night time and The Speck Brothers, astride HORSES, keep pushing their black skinned cargo forward. -

Road Chatter Road Chatter

ROAD CHATTER NORTHERN ILLINOIS REGIONAL GROUP #8 P.O. BOX 803 ARLINGTON HEIGHTS, ILLINOIS 60006 WEB SITE: www.nirgv8.org Volume 53 Issue #5 May 2019 UP NEXT… NIRG Meetings & Events May 05-21-19 Members Meeting 7:30 05-24-19 May 24-27 Spring Fling St. Joseph, Missouri June 06-15-19 Drive Your Ford V-8 Day; Rockford Tour 8:00 am 06-18-19 Members Meeting 7:30 Milestone Commemoration July 1939 Mercury 80th Anniversary 07-11-19 Board Meeting 7:30 This year marks the 80th anniversary of not only the 1939 Mercury but the 07-15-19 Driftless National Tour Mercury line of cars itself. Edsel Ford’s desire to offer a car that would be a step up from the Ford Deluxe and enter the lower medium price class came to 07–16-19 Members Meeting 7:30 fruition with the Mercury. The above 1939 Mercury Sport Convertible be- 07-28-19 NIRG Annual Picnic at longs to Roy Strom of Norman, OK and was photographed by Tom O’Don- nell at our 2014 Central National Meet. Timmermann’s Ranch See full story on Page 8. INSIDE… Monthly column by President Ron Steck ...Page 2 On the Horizon: Upcoming NIRG Events ...Page 3 Rich Harvest Tour Jerry Rich Car Collection ..Page 4 OTHER EVENTS Ford V-8 Cars are Stars of “The Highwaymen” ...Page 6 \ 1939 Mercury 80th Anniversary ...Page 8 May 26th, 2019 8:00am-3:00pm AACA Auto Show & SWAP April Meeting Minutes by Gary Osborne ...Page 10 Sandwich Fair Grounds Drive Down Memory Lane: V-8 Snap Shots ...Page 12 1401 Suydam Road Advertising Section ...Page 13 Sandwich, IL Back cover - Photo of the month: $15.00 entry fee 2019 OFFICERS President Ron Steck A Word From NIRG President Ron Steck Vice President John Scheve he month of May is upon us and spring is in Secretary T full swing. -

Ic/\Ziz Bros:-1

IN ‘CHANGE OF HEART ‘EVER SINCE EVE’ To Present ‘Frolics’ BAN BENITO. May 25 — Pupil* Of BARROW TIP 0 IS REFORMATORY Markoleta Oreer Elstner from Brownsville to Harlingen wl’l par- ticipate In the annual Frolics of 1834 to be presented at the flivoll IS DENIED BY OPERATED ON INMATE SLAIN theater at 8:30 o’clock Friday night, I June 1. The Valley dancing teacher an- nually presents her pupils in a ABOARD spring recital and for this year she I DALLAS COPS BOAT BY AXBLOWS has a number of elaborate brought costumes to this section. More than 75 are expected May 25 —R A LOS ANGELES. May 25. (AV- GATES VILLE, May 28. UPy- pupils I^BdALLA8. to Schmid, Dallas county William Albert Robinson, wealthy Murder charges were filed against participate. The recital will be in connection said Friday that the of- explorer, was reported "doing as L D. Herrin Friday for the ax slay- with the of Stlngaree.* *’ho shot and killed Clyde well a« could be expected” Friday ing of Hobart Lee Hut?. 16-year-old showing ■|Kcers with Irene Dunn and Richard Dix. H^B“arro'*' and Bonnie Parker did not following an appendicitis operation Inmate of the state reformatory MB*V<L 8pecial information which performed by U. 8. Navy surgeons here. ■Efl'd them to a spot southwest of who made a 1,000-mile aerial dash “I aimed to do it last week but ipMhreyeport, La, Wednesday, but to his bedside at Tagus Cove in the the boys wouldn’t let me.” Herrin Retired Teacher It &gM?lectcd that location as the most lonely Galapagos Islands of the purported told a guard at the in- MMaeh' for the desperado couple’s Pacific. -

Wild West Photograph Collection

THE KANSAS CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY Wild West Photograph Collection This collection of images primarily relates to Western lore during the late 19th and parts of the 20th centuries. It includes cowboys and cowgirls, entertainment figures, venues as rodeos and Wild West shows, Indians, lawmen, outlaws and their gangs, as well as criminals including those involved in the Union Station Massacre. Descriptive Summary Creator: Brookings Montgomery Title: Wild West Photograph Collection Dates: circa 1880s-1960s Size: 4 boxes, 1 3/4 cubic feet Location: P2 Administrative Information Restriction on access: Unrestricted Terms governing use and reproduction: Most of the photographs in the collection are reproductions done by Mr. Montgomery of originals and copyright may be a factor in their use. Additional physical form available: Some of the photographs are available digitally from the library's website. Location of originals: Location of original photographs used by photographer for reproduction is unknown. Related sources and collections in other repositories: Ralph R. Doubleday Rodeo Photographs, Donald C. & Elizabeth Dickinson Research center, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. See also "Ikua Purdy, Yakima Canutt, and Pete Knight: Frontier Traditions Among Pacific Basin Rodeo Cowboys, 1908-1937," Journal of the West, Vol. 45, No.2, Spring, 2006, p. 43-50. (Both Canutt and Knight are included in the collection inventory list.) Acquisition information: Primarily a purchase, circa 1960s. Citation note: Wild West Photograph Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri. Collection Description Biographical/historical note The Missouri Valley Room was established in 1960 after the Kansas City Public Library moved into its then new location at 12th and Oak in downtown Kansas City.