Savannah River Basin, Wilderness Abounds and Diversity Astounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT ROBINSON, JASON LESLEY. Discontinuities in Fish Assemblages and Efficacy of Thermal Restoration in Toxaway River, NC

ABSTRACT ROBINSON, JASON LESLEY. Discontinuities in fish assemblages and efficacy of thermal restoration in Toxaway River, NC (Under the direction of Peter S. Rand) Biogeographical studies in the Toxaway and Horsepasture Rivers, (Transylvania County, NC) were initiated along with the creation of a state park in the area. This region is noted for extreme topographic relief, high annual rainfall totals and many rare and endemic plants and animals. The study area encompasses a portion of the Blue Ridge Escarpment and the associated Brevard Fault Zone. These geologic features are important factors in determining the distribution of stream habitats and organisms. I hypothesize that major waterfalls and cascade complexes have acted to discourage invasion and colonization by fishes from downstream. This hypothesis is supported by longitudinal fish assemblage patterns in study streams. Fish species richness in Toxaway River increased from 4 to 23 between Lake Toxaway and Lake Jocassee, a distance of 10 river kilometers. No species replacement was observed in the study area, but additions of up to 7 species were observed in assemblages below specific waterfalls. A second component of the research examines the efficacy of a rapid bioassessment procedure in detecting thermal and biological changes associated with a reservoir mitigation project in an upstream site on Toxaway River. The mitigation project began in the winter of 2000 with the installation of a hypolimnetic siphon to augment the overflow release with cooler water during summer months. I record a greater summer temperature difference on Toxaway River below Lake Toxaway (comparison of pre- vs. post-manipulation), relative to control sites. -

AGENDA 6:00 PM, MONDAY, NOVEMEBR 20Th, 2017 COUNCIL CHAMBERS OCONEE COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE COMPLEX

AGENDA 6:00 PM, MONDAY, NOVEMEBR 20th, 2017 COUNCIL CHAMBERS OCONEE COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE COMPLEX 1. Call to Order 2. Invocation by County Council Chaplain 3. Pledge of Allegiance 4. Approval of Minutes a. November 6th, 2017 5. Public Comment for Agenda and Non-Agenda Items (3 minutes) 6. Staff Update 7. Election of Chairman To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 8. Discussion on Planning Commission Schedule for 2018 To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 9. Discussion on the addition of the Traditional Neighborhood Development Zoning District To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 10. Discussion on amending the Vegetative Buffer [To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 11. Discussion on the Comprehensive Plan review To include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required. a. Discussion by Commission b. Commission Recommendation 12. Old Business [to include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required] 13. New Business [to include Vote and/or Action on matters brought up for discussion, if required] 14. Adjourn Anyone wishing to submit written comments to the Planning Commission can send their comments to the Planning Department by mail or by emailing them to the email address below. Please Note: If you would like to receive a copy of the agenda via email please contact our office, or email us at: [email protected]. -

Stream-Temperature Characteristics in Georgia

STREAM-TEMPERATURE CHARACTERISTICS IN GEORGIA By T.R. Dyar and S.J. Alhadeff ______________________________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4203 Prepared in cooperation with GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Atlanta, Georgia 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 3039 Amwiler Road, Suite 130 Denver Federal Center Peachtree Business Center Box 25286 Atlanta, GA 30360-2824 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 2 Previous investigations. 2 Station-identification system . 3 Stream-temperature data . 3 Long-term stream-temperature characteristics. 6 Natural stream-temperature characteristics . 7 Regression analysis . 7 Harmonic mean coefficient . 7 Amplitude coefficient. 10 Phase coefficient . 13 Statewide harmonic equation . 13 Examples of estimating natural stream-temperature characteristics . 15 Panther Creek . 15 West Armuchee Creek . 15 Alcovy River . 18 Altamaha River . 18 Summary of stream-temperature characteristics by river basin . 19 Savannah River basin . 19 Ogeechee River basin. 25 Altamaha River basin. 25 Satilla-St Marys River basins. 26 Suwannee-Ochlockonee River basins . 27 Chattahoochee River basin. 27 Flint River basin. 28 Coosa River basin. 29 Tennessee River basin . 31 Selected references. 31 Tabular data . 33 Graphs showing harmonic stream-temperature curves of observed data and statewide harmonic equation for selected stations, figures 14-211 . 51 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing locations of 198 periodic and 22 daily stream-temperature stations, major river basins, and physiographic provinces in Georgia. -

Hiking the Appalachian and Benton Mackaye Trails

10 MILES N # Chattanooga 70 miles Outdoor Adventure: NORTH CAROLINA NORTH 8 Nantahala 68 GEORGIA Gorge Hiking the Appalachian MAP AREA 74 40 miles Asheville co and Benton MacKaye Trails O ee 110 miles R e r Murphy i v 16 Ocoee 64 Benton MacKaye Trail Whitewater Center Appalachian Trail Big Frog 64 Wilderness 69 175 1 Springer Mountain (Trail Copperhill TENNESSEE NORTH CAROLINA Terminus for AT & BMT) GEORGIA GEORGIA McCaysville GEORGIA 75 2 Three Forks 15 Epworth spur 3 Long Creek Falls T 76 o 60 Hiwassee 2 c 2 5 c 129 4 Woody Gap Cohutta o Wilderness S BR Scenic RRa 60 Young F R Harris 288 5 Neels Gap, Walasi-Yi iv e Mineral r Center 14 Blu 2 6 Tesnatee Gap, Richard Mercier Brasstown Russell Scenic Hwy. Orchards F Bald S 64 13 Lake Morganton Blairsville 7 Unicoi Gap Blue 515 17 Ridge old 8 Toccoa River & Swinging Blue 76 Ridge 129 Bridge A s k a 60 9 Wilscot Gap, Hwy 60 R oa 180 Benton TrailMacKaye d 7 10 Shallowford Bridge 12 10 11 Stanley Creek Rd. 9 Vogel Cooper Creek State Park 11 Scenic Area 12 Fall Branch Falls Rich Mtn. 75 Dyer Gap Wilderness 13 515 8 180 5 14 Watson Gap Tocc 6 oa River 348 15 Jacks River Trail 52 BMT Trail Section Distances (miles) (6.0) Springer Mountain - Three Forks 19 Helen (Dally Gap) (1.1) Three Forks - Long Creek Falls 3 60 16 Thunder Rock (8.8) Three Forks - Swinging Bridge FS Ellijay (14.5) Swinging Bridge - Wilscot Gap 58 Suches Campground (7.5) Wilscot Gap - Shallowford Bridge F S Three (33.0) Shallowford Bridge - Dyer Gap 4 Forks 4 75 (24.1) Dyer Gap - US 64 2 2 Main Welcome Center Appalachian Trail -

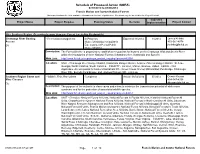

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2014 to 09/30/2014 Francis Marion and Sumter National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R8 - Southern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Chattooga River Boating - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:11/2014 11/2014 James Knibbs Access Notice of Initiation 07/24/2013 803-561-4078 EA Est. Comment Period Public [email protected] Notice 07/2014 Description: The Forest Service is proposing to establish access points for boaters on the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River within the boundaries of three National Forests (Chattahoochee, Nantahala and Sumter). Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=42568 Location: UNIT - Chattooga River Ranger District, Nantahala Ranger District, Andrew Pickens Ranger District. STATE - Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina. COUNTY - Jackson, Macon, Oconee, Rabun. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Access points for boaters:Nantahala RD - Green Creek; Norton Mill and Bull Pen Bridge; Chattooga River RD - Burrells Ford Bridge; and, Andrew Pickens RD - Lick Log. Southern Region Caves and - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Completed Actual: 06/02/2014 07/2014 Dennis Krusac Mine Closures 404-347-4338 CE [email protected] Description: The purpose of the action is to close caves and mines to minimize the transmission potential of white nose -

15A Ncac 02B .0100-.0300

NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Division of Water Resources Administrative Code Section: 15A NCAC 02B .0100: Procedures for Assignment of Water Quality Standards 15A NCAC 02B .0200: Classifications and Water Quality Standards Applicable to Surface Waters and Wetlands of North Carolina 15A NCAC 02B .0300: Assignment of Stream Classifications Amended Effective: November 1, 2019 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT COMMISSION RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA This document available at: https://files.nc.gov/ncdeq/csrrb/tri_rev_17to19/15A_NCAC_02B_.0100- .0300.pdf SUBCHAPTER 02B - SURFACE WATER AND WETLAND STANDARDS SECTION .0100 - PROCEDURES FOR ASSIGNMENT OF WATER QUALITY STANDARDS 15A NCAC 02B .0101 GENERAL PROCEDURES (a) The rules contained in Sections .0100, .0200 and .0300 of this Subchapter, which pertain to the series of classifications and water quality standards, shall be known as the "Classifications and Water Quality Standards Applicable to the Surface Waters and Wetlands of North Carolina." (b) The Environmental Management Commission (hereinafter referred to as the Commission), prior to classifying and assigning standards of water quality to any waters of the State, shall proceed as follows: (1) The Commission, or its designee, shall determine waters to be studied for the purpose of classification and assignment of water quality standards on the basis of user requests, petitions, or the identification of existing or attainable water uses, as defined by Rule .0202 of this Subchapter, not presently included in the water classification. (2) In determining the best usage of waters and assigning classifications of such waters, the Commission shall consider the criteria specified in G.S. 143-214.1(d). In determining whether to revise a designated best usage for waters through a revision to the classifications, the Commission shall follow the requirements of 40 CFR 131.10 which is incorporated by reference including subsequent amendments and editions. -

Watershed Organizations in the Southeast Handout Watershed Organizations in the Southeast Handout

E | Attachment E: in the Organizations Watershed Southeast Handout Southeast Watershed Organizations in the Southeast Handout • Lake Lanier Handout - Alternative Nutrient Strategies Brown and Caldwell Alternative Nutrient Strategies This brochure provides information on watershed based collaboration for protecting and enhancing water quality and quantity. Examples from the southeastern United States are presented to show possibilities for further cooperation in the Lake Lanier watershed. Lake Lanier is a vital resource for its immediate restore compliance. These plans may be called neighbors and beyond, including portions of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs). The plans Georgia, Florida, and Alabama. Lake Lanier may be developed with the use of models and provides water supply and multiple recreation may impose limitations on point sources and/or opportunities including boating and fishing. nonpoint sources. Protecting the lake is important to all stakeholders, especially now regarding nutrients. Since before the lake was created in the 1950s, stakeholders have worked to protect the lake Since the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, through water conservation, sophisticated the water quality and biological health of thousands wastewater treatment, stormwater management, of waterbodies have been evaluated. State and/or river cleanup events, and other efforts. As growth federal environmental agencies set a water use continues in the watershed, additional efforts will be classification for each waterbody, such as fishing, necessary to -

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

Tourism Asset Inventory

Asset Asset Management Overview Natural/Scenic Asset Details Cultural/Historic Asset Details Event Asset Details Type: Brief Description Potential Market Draw: Access: Uses: Ownership Supporting Critical Asset is Key Tourism Opportunities are Land Visitor Use Management Interpretation Ranger at Site Visitor Potential Land Protection Species Represents the Type of Cultural Representation has Promotion of event Attendance of Event Event results Event has a NGOs Management marketed through Impact Indicators provided to businesses, Management Policy or Plan Plans Included at Site Facilities at Hazards Status Protection cultural heritage of the Heritage Represented: the support of a is primarily: event is Duration: in increased specific Natural, Cultural, Day Visit, Overnight, 1 = difficult Hiking, Biking, Issues Destination are Being visitors, and community Plan in Place Stakeholder Site Status region diverse group of primarily: overnight marketing Historic, Scenic, Extended 5 = easy Paddling, Marketing Monitored on a members to donate Input Tangible, Intangible, stakeholders Locally, Regionally, One Day, stays in strategy and Event, Educational, Interpretation, Organization / Regular Basis time, money, and/or Both Nationally, Locally, Multiple Days destination economic Informational etc. TDA and Reported to other resources for Internationally, All Regionally, impact TDA asset protection Nationally, indicators Internationally, All Pisgah National Forest Natural Established in 1916 and one of the first national Day Visit, Overnight, 5; PNF in Hiking, Biking, U.S. Federal Pisgah Overcrowding Yes Yes, in multiple ways Nantahalla and y,n - name, year Yes; National At various placs at various At various Any hazard Federally protected See Forest forests in the eastern U.S., Pisgah stretches across Extended Transylvania Rock Climbing, Government Conservancy, at some popular through multiple Pisgah forest Forest listed below locations below locations below associated with public lands for Management several western North Carolina counties. -

0306010606 Augusta Canal-Savannah River HUC 8 Watershed: Middle Savannah

Georgia Ecological Services U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2/9/2021 HUC 10 Watershed Report HUC 10 Watershed: 0306010606 Augusta Canal-Savannah River HUC 8 Watershed: Middle Savannah Counties: Burke, Columbia, Richmond Major Waterbodies (in GA): McBean Creek, Savannah River, Butler Creek, Boggy Gut Creek, Reed Creek, Newberry Creek, Rocky Creek, Phinizy Swamp, Fort Gordon Reservoir, Bennock Millpond, Lake Olmstead, Millers Pond Federal Listed Species: (historic, known occurrence, or likely to occur in the watershed) E - Endangered, T - Threatened, C - Candidate, CCA - Candidate Conservation species, PE - Proposed Endangered, PT - Proposed Threatened, Pet - Petitioned, R - Rare, U - Uncommon, SC - Species of Concern. Shortnose Sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum) US: E; GA: E Occurrence; Please coordinate with National Marine Fisheries Service. Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus) US: E; GA: E Occurrence; Please coordinate with National Marine Fisheries Service. Wood Stork (Mycteria americana) US: T; GA: E Potential Range (county); Survey period: early May Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis) US: E; GA: E Occurrence; Survey period: habitat any time of year or foraging individuals: 1 Apr - 31 May. Frosted Flatwoods Salamander (Ambystoma cingulatum) US: T; GA: T Potential Range (county); Survey period: for larvae 15 Feb - 15 Mar. Canby's Dropwort (Oxypolis canbyi) US: E; GA: E Potential Range (soil type); Survey period: for larvae 15 Feb - 15 Mar. Relict Trillium (Trillium reliquum) US: E; GA: E Occurrence; Survey period: flowering 15 Mar - 30 Apr. Use of a nearby reference site to more accurately determine local flowering period is recommended. Updated: 2/9/2021 0306010606 Augusta Canal-Savannah River 1 Georgia Ecological Services U.S. -

Yadkin River Huc 03040201

BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT UNIT BASINWIDE ASSESSMENT REPORT SAVANNAH RIVER BASIN NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Water Quality Environmental Sciences Section November 2010 This page was intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page INTRODUCTION TO PROGRAM METHODS .............................................................................................. 4 BASIN DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................................................. 4 SAVANNAH RIVER HU 03060101 – SENECA RIVER ................................................................................ 6 River and Stream Assessment .............................................................................................................. 6 Special Studies ...................................................................................................................................... 7 SAVANNAH RIVER HU 03060102 – TUGALOO RIVER ............................................................................. 8 River and Stream Assessment .............................................................................................................. 8 GLOSSARY ................................................................................................................................................ 10 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix Page B-1. Summary of benthic macroinvertebrate data, sampling methods and criteria. ................................12 S-1. Benthic site -

Section 305(B) Assessment and Reporting

State of South Carolina Integrated Report for 2012 Part II: Section 305(b) Assessment and Reporting May 24, 2012 PREFACE The South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (SCDHEC) prepared this report as a requirement of Section 305(b) of Public Law 100-4, last reauthorized and commonly known as The Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1987, and as a public information document. The report presents a general assessment of water quality conditions and water pollution control programs in South Carolina. SCDHEC has published Watershed Water Quality Management Assessments (WWQA), that contain information pertaining to the specific watersheds and give a more complete picture of the waters referenced in this document. While the title page states that this is an integrated report, Section 303(d) of the CWA requirements are submitted separately as a companion document. The determinations of surface water quality were based on data collected by SCDHEC at ambient water quality monitoring stations, point source permit required monitoring, and evaluation of nonpoint source (NPS) data. Other information in this report was obtained from SCDHEC programs associated with water quality monitoring and water pollution control. i TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE........................................................................................................................................ i TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................................