Ethics, Politics, and Alterity in Selected Plays and Other Works by Harold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PMQ400-E Dumbwaiter Planning Guide.Indd

Planning Guide Cable-Waiter™ Paca-Waiter® Dumbwaiters W E CABLE-WAITER™ & PACA-WAITER® PLANNING GUIDE PMQ0400.1 W E CABLE-WAITER™ & PACA-WAITER® PLANNING GUIDE PMQ0400.2 We are a proud member of the Accessibility Equipment Manufacturers Association. This symbol assures you of our commitment to high quality and accessibility to everyone. Waupaca Elevator Mission Statement Our company’s mission is to supply and service products that meet W E or exceed our customers’ expectations of high quality, value, delivery and longevity. Our success is a direct refl ection of our employees’ involvement and commitment to excellence. We strive to continuously improve our products to ensure meeting the future requirements of our customers and facilitate competitive growth. CSI 3-Part Specifi cations Customize and download CSI 3-Part Specifi cations by logging on to: www.arcat.com - specify Waupaca Elevator as the requested manufacturer www.waupacaelevator.com - go to “Architect Section” click on linking icon Table of Contents Introduction & Planning Steps ...................................................................... 4 Dumbwaiter Reference Chart ........................................................................ 5 Car Gate Reference Chart ................................................................................ 6 Commercial Hoistway Door Reference Chart .......................................... 7 Hoistway Layout ...........................................................................................8-14 Elevation Layout .........................................................................................15-17 -

Improvement Codes Building Attributes

IMPROVEMENT CODES CODE TYPE IMPROVEMENT CODE TYPE IMPROVEMENT CODE TYPE IMPROVEMENT BD1 Light Boat Dock FP Fire Place MAA Main Area Addition or Mobile Home BD2 Medium Boat Dock FP1 Fire Place Class 1 MBH Masonry Boat House BD3 Heavy Boat Dock FP2 Fire Place Class 2 MUB Masonry Utility Building BW Breezeway FUB Metal or Frame Utility Building OB Out Building CA Central Air GA Attached Garage OP Open Porch CH Central Heat GH Greenhouse SP Screen Porch CP1 Carport 1, Wood/Concrete HE Heatalator SPA Spa CP2 Carport 2, Wood/Dirt HO Hoist SPOOL Small Pool CP3 Carport 3, Metal/Dirt HT Hot Tub / Jacuzzi ST Storage (Attached to House) CP4 Carport 4, Under Beach House LPOOL Large Pool STG Storage (Detached from House) CPY Canopy MA Main Area 1 Story SV Salvage DG Detached Garage MA1 Main Area 1.5 Story WD Wood Deck EP Enclosed Porch MA2 Main Area 2 Story XPOOL Extra Large Pool FBH Metal or Frame Boat House MA2.5 Main Area 2.5 Story ELV Dumbwaiter or Elevator MA3 Main Area 3 Story BUILDING ATTRIBUTES CONSTRUCTION STYLE EXTERIOR FINISH FOUNDATION SF-M Single Family Modern BV Brick Veneer CS Concrete Slab SF-C Single Family Conventional WF Wood Frame PB Pier & Beam SF-S Single Family Spanish COMP Composition WPR Wood Piers MF-C Multi Family Conventional ST Stucco WOK Wood Pilings R-CT Recreation - Comp Type CB Concrete Blocks PT Post Tension Concrete L-CM Light Commercial AS Asbestos BW Brick & Wood INTERIOR FINISH SV Stone SR Sheetrock ROOF STYLE SI Sheet Iron PA Panel HP Hip SS Structural Steel WP Wallpaper GA Gable WS Wood Shingle FLOORING CS Composition -

2017 Florida Building Code - Residential, Sixth Edition (First Printing: Jul 2017) SECTION R 321 ELEVATORS and PLATFORM LIFTS R321.1 Elevators

2017 Florida Building Code - Residential, Sixth Edition (First Printing: Jul 2017) SECTION R 321 ELEVATORS AND PLATFORM LIFTS R321.1 Elevators. Where provided, passenger elevators, limited-use and limited-application elevators or private residence elevators shall comply with ASME A17.1/CSA B44. R321.2 Platform lifts. Where provided, platform lifts shall comply with ASME A18.1. R321.3 Accessibility. Reserved. R321.4 Clearance requirements between elevator doors for elevators inside a private residence. R321.4.1 For elevators installed in a private residence: 1. (a)The distance between the hoistway face of the hoistway doors and the hoistway edge of the 3 1 landing sill may not exceed /4 inch for swinging doors and 2 /4 inches for sliding doors. 2. (b) 1. 1.Horizontal sliding car doors and gates shall be designed and installed to withstand a force of 75 pounds applied horizontally on an area 4 inches by 4 inches at right angles to and at any location on the car door without permanent deformation. The deflection may not 3 exceed /4 inch and may not displace the door from its guides or tracks. The force must be applied while the door is in the fully closed position. 2. 2.Folding car doors shall be designed and installed to withstand a force of 75 pounds applied horizontally using a 4-inch-diameter sphere at any location within the folds on the car door 3 without permanent deformation. The deflection may not exceed /4 inch and may not displace the door from its guides or tracks. The force must be applied while the door is in the fully closed position. -

Inclinator Dumbwaiter Brochure

INCLINATOR® DUMBWAITERS Commercial grade to home use Commercial Dumbwaiters Providing convenience and safety for employees. Stop carrying heavy or bulky items D up and down stairs. A Reduce the risk of back strain, aching muscles and even accidents by installing B an Inclinator Dumbwaiter. For businesses, a Workers’ Comp claim could easily exceed the cost of a Dumbwaiter. Can be used as counter-loading or floor-loading. The commercial dumbwaiter is great for restaurants, hospitals, medical practices, office buildings and other public buildings. The energy-efficient drive system requires just 220V electrical. DUMBWAITER C • Custom sizes up to 36” x 36” x 48” (91.4 cm x 91.4 cm x 121.9 cm) • Weight capacities: 200 lb. (90 kg), 300 lb. (136 kg) and 500 lb. (226 kg) • Travel: up to 27 ft. (8.2 m) on 200 lb. (90 kg) model, up to 47 ft. (14.3 m) on 300 lb. (136 kg) and 500 lb. (226 kg) models Hoistway Doors Call Buttons • Up to 6 stops • Automatic controls from any level A • Can accommodate openings on 1, 2 C or 3 sides • Painted steel cab or optional stainless steel • 220V electrical Bi-parting Slide-up Swing Cab Gates Arrival Gong D B Bi-parting Slide-up Collapsible (where allowable by law) Residential Dumbwaiters Walk up and down stairs empty-handed. Move things from floor to floor easily and safely. Inclinator’s Homewaiter® residential dumbwaiter is ideal for transporting groceries from garage to kitchen, laundry from bedrooms to utility room, bottles and cases from/to a wine cellar, and hauling firewood from ground level to living space. -

The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter

Ben Ferber The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter I have no doubt that history will recognize Harold Pinter as one of the most influential dramatists of all time, a perennial inspiration for the way we look at modern theater. If other playwrights use characters and plots to put life under a microscope for audiences, Pinter hands them a kaleidoscope and says, “Have at it.” He crafts multifaceted plays that speak to the depth of his reality and teases and threatens his audience with dangerous truths. In No Man’s Land, Pinter has Hirst attack Spooner, who may or may not be his old friend: “This is outrageous! Who are you? What are you doing in my house?”1 Hirst then launches into a monologue beginning: “I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it which might remind you of your own, of what you once were.”2 Pinter never fully resolves Spooner’s identity, but the mens’ actions towards each other are perfectly clear: with exacting language and wit, Pinter has constructed a magnificent struggle between the two for power and identity. In 1958, early in his career, Pinter wrote The Hothouse, an incredibly funny play based on a traumatic personal experience as a lab rat at London’s Maudsley Hospital, proudly founded as a modern psychiatric institution, rather than an asylum. The story of The Hothouse, set in a mental hospital of some sort, is centered around the death of one patient, “6457,” and the unexplained pregnancy of another, “6459.” Details around both incidents are very murky, but varying amounts of culpability for both seem to fall on the institution’s leader, Roote, and his second-in- command, Gibbs. -

“Dr” Dumbwaiter Maintenance & Parts Manual

AMBASSADOR “DR” DUMBWAITER MAINTENANCE & PARTS MANUAL Matot Inc., 2501 Van Buren, Bellwood, IL 60104 (708) 547-1888 Main (708) 547-1608 Fax (800) 369-1070 Sales Website: www.matot.com E-mail: [email protected] The maintenance of Matot Drum Dumbwaiters should only be performed by qualified, experienced, and trained elevator installers. Working in the dumbwaiter hoistway and on dumbwaiter equipment can be hazardous. All Safety Rules associated with installing elevator type equipment must be followed at all times. Proper protective equipment must be used at all times during maintenance and repair of the dumbwaiter equipment. Read this manual carefully. Be thoroughly familiar with all parts and procedures before attempting any maintenance or repair functions on this equipment. MATOT, INC. AMBASSADOR “DR” MAINTENANCE AND PARTS Table of Contents Page General Operation & Signals ……………………………………….. 1 Operation of Special Equipment …………………………………… 2 Suggested Maintenance ……………………………………………… 3–4 Reducer Information ………………………………………………… 5–10 Stearns Brake Information ………………………………………….. 11–18 Reverse Phase Data Sheet …………………………………………… 19-20 Pushbutton Detail ……………….…………………………………… 21 Slack Cable Identification……………………………………………. 22 Motor Overload Data Sheet …………………………………………. 23 Door Interlock ……………………………………………………….. 24-25 Power Gate & Door Adjustment Procedures & Diagrams ……….. 26–29 Power Gate Parts Identification……………………………………... 30-32 Power Gate Troubleshooting Guide ………………………………… 33 Dumbwaiter Troubleshooting Guide ……………………………….. 34 Replacement Parts Listing …………………………………………… 35–36 GENERAL OPERATION OF STANDARD ELECTRIC DUMBWAITERS: The dumbwaiter unit has a automatic call and send operation. Momentary pressure applied to the Pushbutton will operate the unit. There is typically a full bank of buttons at each landing for each floor served. These buttons are used to call and send the car to different floors. The car will stop automatically at the landing it is sent or called to by means of limit switches. -

Destination Medical Center Corporation Board of Directors Meeting

Destination Medical Center Corporation Board of Directors Meeting Wednesday, February 3, 2021 9:30 A.M. DESTINATION MEDICAL CENTER CORPORATION (DMCC) BOARD MEETING Wednesday, February 3, 2021 9:30 A.M.** Following the March 13, 2020 Declaration of Peacetime Emergency by Governor Walz (as may be amended), the Destination Medical Center Corporation (DMCC) is holding its regularly scheduled February 3, 2021 9:30 AM meeting by telephone or other electronic means, according to Minnesota Statutes, Section 13D.021. DMCC Chair Rybak has concluded that an in-person meeting and the regular meeting location for the DMCC are not practical or prudent because of the health pandemic declared under the Emergency Order and according to current guidance from the Minnesota Department of Health and the CDC. The public may monitor the meeting by calling the phone number listed below (#2) or on-line through the link below (#3). In addition, public comments may be offered by submitting written comments to [email protected], or by telephone or videoconference during the Public Comment item on the Agenda, as follows: 1. Sign up at least one hour before the meeting by sending your full name, telephone number and email address to [email protected]. 2. To join the meeting by telephone, dial 1-888-788-0099; when prompted, enter meeting ID 833 9479 8623. 3. To join the meeting by videoconference, use the following link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83394798623 AGENDA PAGE I. Call to Order II. Roll Call III. Approval of Agenda 1 IV. Approval of Minutes: November 19, 2020 3 V. -

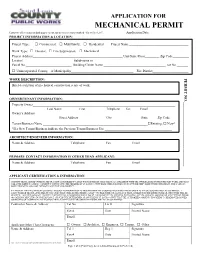

Mechanical Permit Application

APPLICATION FOR MECHANICAL PERMIT Complete all sections on both pages except for the two sections marked “For Office Use”. Application Date_____________________________ PROJECT INFORMATION & LOCATION: Project Type: □ Commercial, □ Multifamily, □ Residential Project Name:____________________________________ Work Type: □ Elevator, □ Fire Suppression, □ Mechanical Project Address_______________________________________________________ Unit/Suite/Floor_________ Zip Code__________ Locator/ Subdivision or Parcel No.____________________________ Building/Center Name ______________________________________ Lot No._______ □ Unincorporated County, or Municipality______________________________________ Fire District______________________ WORK DESCRIPTION: NO. PERMIT Brief description of mechanical construction scope of work: OWNER/TENANT INFORMATION: ____________________________________ Property Owner_______________________________________________________________________________________ Last Name First Telephone Fax Email Owner’s Address ______________________________________________________________________________________ Street Address City State Zip Code Tenant/Business Name ________________________________________________________________□Existing, □ New* *If a New Tenant/Business indicate the Previous Tenant/Business Use _________________________________________ ARCHITECT/ENGINEER INFORMATION: Name & Address Telephone Fax Email If New Tenant/Business Indicate The Previous Tenant/Business Use _____________________________________ PRIMARY CONTACT -

An Art Center for Wellesley College Thesis Report for Degree of Master in Architecture

AN ART CENTER FOR WELLESLEY COLLEGE THESIS REPORT FOR DEGREE OF MASTER IN ARCHITECTURE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MAY 12, 1950 RICHARD C. REECE L. B. ANDERSON, HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE T- The Graduate House Cambridge 39, Massachusetts May 12, 1950 Prof. L. B. Anderson Head of Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge 39, Massachusetts Dear Prof. Anderson: As partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Architecture, I submit this thesis entitled "An Art Center for Wellesley College." Respectfully yours, Richard C. Reece ACKNOWLEDGMENT, with appreciation, is given to the following groups: Faculty and staff members: School of Architeoture and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Art Department, Wellesley College Administration, Wellesley College School of Architecture, Harvard University Art Department, Vassar College Staff members: Fogg Museum, Cambridge Metropolitan Museum, New York City TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD 1 ABOUT WELLESLEY: THE PREPARATION AND THE PRODUCT 2 The 75th Anniversary Fund 7 THE GROWTH OF THE COLLEGE 9 The Present Art Building 16 ART EDUCATION 19 Members of the Art Department 21 The Curriculum 22 MORE GOTHIC? 35 Resistance to What? 43 Nothing Watered-Down 45 THE SITE 48 PROGRAM FOR A NEW ART BUILDING 52 REVISIONS AND ADDITIONS 60 Zone I: The library 60 Miscellaneous 62 Zone II: Classrooms 63 Zone IV: The gallery 63 Miscellaneous 67 B IBLIOGRAPHY 68 FOREWORD The present art building at Wellesley College is inadequate and unsuitable for the teaching of art in its various forms. The College proposes to build a new art center on nearly the same site as the old, a decision agreeably in accordance with the choice of a professional site selector. -

Dumbwaiter Installation Guide

Quick Serve 200 DumBwaiter Installation Guide QS-200 Required Tools: • Impact driver • Drill • Sawzall/Miter Saw (to cut aluminum track to length) • RuBBer mallet • Ratchets, sockets, wrenches- ½”, 7/16”, 9/16”, ¾” • Screw drivers- small wiring screwdriver, standard #2 phillips head • adapters for impact • Ladder Introduction: • The QS-200 has a maximum load capacity of 200Lbs and travels at approximately 32 fpm. • The car may be called or sent to any floor level, from any floor level. • The doors will only open when the car is present, and it will only move if all doors are closed. • The QS-200 is a dumBwaiter designed and manufactured in compliance with ASME A17.1 standards. The track and car frame are machined aluminum equipped with roller guides and a broken cable safety system. The car is equipped with Bi-parting doors, a removable shelf, and is available in white laminate, pre-finished Birch, or marine grade plastic. This dumBwaiter is intended to transport Non-Living cargo only, absolutely no passengers are permitted. • The system requires a 110 vac circuit, 15amp. The power source should Be located where the motor is intended to mount (top or Bottom). The controller is shipped with a standard cord end to plug into a standard 15amp outlet. Some jurisdictions may require a disconnect-in which case it will Be necessary to remove the cord end and hardwire directly to the disconnect. • When possiBle, it is significantly easier to install this dumBwaiter with the front wall of the dumbwaiter shaft open, or at least the very top or very Bottom section. -

Dumbwaiters for Homes, Offices, Medical Practices, Stores, Restaurants, Banks, Libraries and Many Other Applications

Inclinator’s innovation and reliability can be found in our line of Dumbwaiters for homes, offices, medical practices, stores, restaurants, banks, libraries and many other applications. Reduce the risk of back strain, aching muscles and even accidents. Stop carrying heavy or bulky items up and down stairs and install an Inclinator Dumb - waiter. For businesses, a Workers’ Comp claim could easily exceed the cost of a Dumbwaiter. Built to perform … and last. Inclinator is known for providing custom lift solutions, so give us your requirements – however unique they may be – and we’ll deliver an ideal design. Besides functionality, Inclinator Dumbwaiters feature solid construction and proven reliability. Dumbwaiter For commercial and • 220V electrical with flexible power Safety & Reliability residential use unit location FEATURES • Rolled steel rail mounted to 2” x 12” • Custom sizes up to 36” x 36” x 48” plank • • Up to 500 lb. capacity Energy-efficient cable drum drive • • Can be installed at counter or floor level Broken cable safety device and slack cable disconnect • Maximum travel distance of 50 ft. • Meets all code requirements for • Automatic controls from any floor safety • Can accommodate openings on 1, 2 or • All door options meet 1.5-hour (B) fire 3 sides rating from UL • Hoistway door options include slide • Knock-down construction standard Car cam and roller Key lock and door open up, bi-parting, swing, machine access position shut-off switch shut-off switch meet all • 2-year warranty meet all industry codes as industry codes for a • Car gate options include collapsible a dumbwaiter door safety machine room access and bi-parting • Made in the USA interlock. -

204 Church Street (Residence of Architect Arnout Cannon)

Statement of Significance: 204 Church Street (Residence of architect Arnout Cannon) Prepared by: Design Historian Holly Wahlberg on behalf of City Councilman Chris Petsas Date: September 26, 2014 Criteria: identified with historic personages; embodies the distinguishing characteristics of an architectural style; is the work of a designer whose work has significantly influenced Poughkeepsie’s architectural heritage 204 Church Street was built in 1887 by Poughkeepsie architect Arnout Cannon, Jr. (1839-1898) as Cannon’s personal home and office. As the son of a prominent Poughkeepsie builder, Cannon served a four year carpentry apprenticeship starting at age 15 under his father’s training followed by two years of architectural study in the New York City office of architect Frederick Diaper. (All four of Cannon’s brothers - Charles, George, William, and Cornelius - became carpenters, and Can- non frequently partnered with his brother Cornelius throughout his career.) Except for a period of distinguished service in the Union army during the Civil War where he served as Lieutenant Colonel of the 97th United States Colored Infantry, Cannon remained in Poughkeepsie his entire life practicing residential, school, church, and commercial architecture in his native city and throughout the Hudson Valley in places such as Rhinebeck, Red Hook, Highland, New Paltz, Newburgh, Milton, Marlborough, Yonkers, and Beacon. One architect who got his start on Can- non’s staff, Percival Lloyd, went on to design some of Poughkeepsie’s finest buildings. At the start of his career, Cannon supplemented his architectural practice by acting as a builder. His work as a builder includes some of Poughkeepsie’s most notable landmarks: Vassar Brothers Old Men’s Home (Cunneen-Hackett), Vassar Col- lege Chemistry Laboratory Building, the John P.