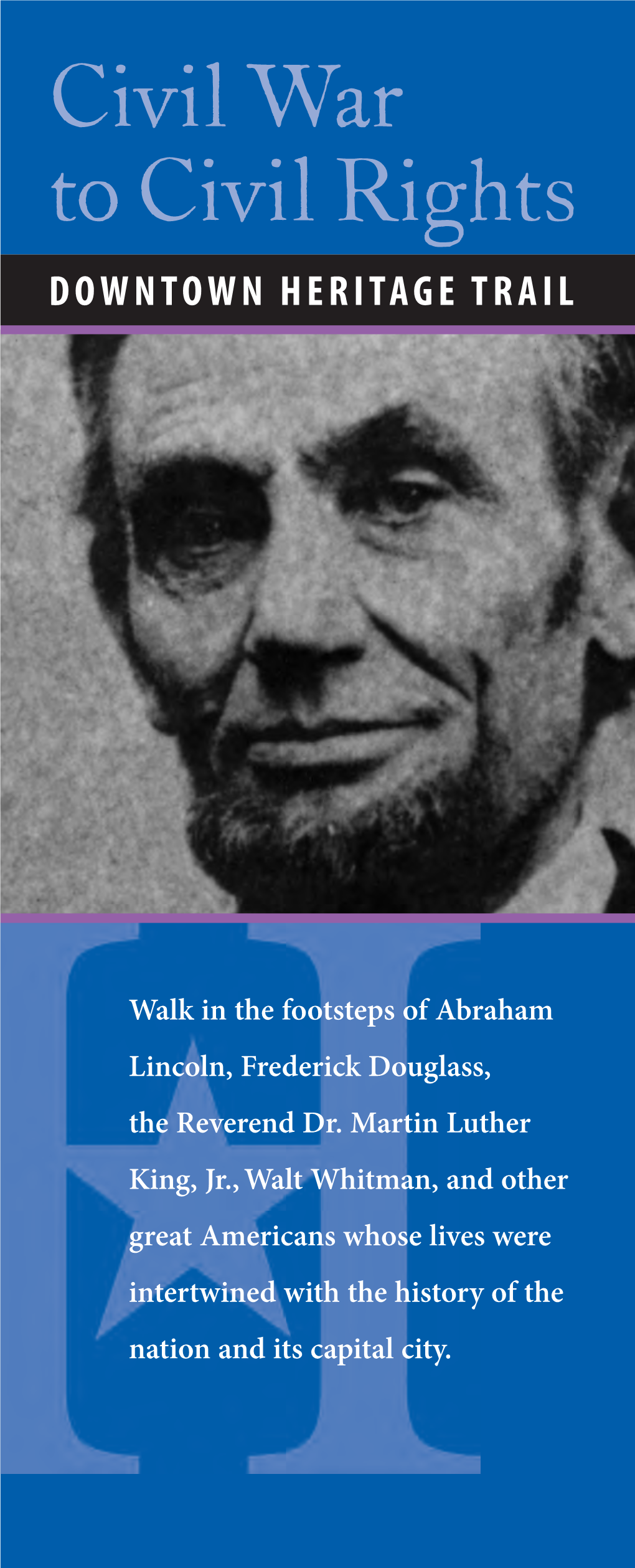

Civil War to Civil Rights Downtown Heritage Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village in the City Historic Markers Lead You To: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail – a Pre-Civil War Country Estate

On this self-guided walking tour of Mount Pleasant, Village in the City historic markers lead you to: MOUNT PLEASANT HERITAGE TRAIL – A pre-Civil War country estate. – Homes of musicians Jimmy Dean, Bo Diddley and Charlie Waller. – Senators pitcher Walter Johnson's elegant apartment house. – The church where civil rights activist H. Rap Brown spoke in 1967. – Mount Pleasant's first bodega. – Graceful mansions. – The first African American church on 16th Street. – The path President Teddy Roosevelt took to skinny-dip in Rock Creek Park. Originally a bucolic country village, Mount Pleasant has been a fashion- able streetcar suburb, working-class and immigrant neighborhood, Latino barrio, and hub of arts and activism. Follow this trail to discover the traces left by each succeeding generation and how they add up to an urban place that still feels like a village. Welcome. Visitors to Washington, DC flock to the National Mall, where grand monuments symbolize the nation’s highest ideals. This self-guided walking tour is the seventh in a series that invites you to discover what lies beyond the monuments: Washington’s historic neighborhoods. Founded just after the Civil War, bucolic Mount Pleasant village was home to some of the city’s movers and shakers. Then, as the city grew around it, the village evolved by turn into a fashionable streetcar suburb, a working-class neigh- borhood, a haven for immigrants fleeing political turmoil, a sometimes gritty inner-city area, and the heart of DC’s Latino community. This guide, summariz- ing the 17 signs of Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail, leads you to the sites where history lives. -

The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2006 Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction Miya G. Abbot University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Abbot, Miya G., "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1487 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. Abbot entitled "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of , with a major in English. Miriam Thaggert, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary Jo Reiff, Janet Atwill Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. -

Discover Woman American History

soei D g American Democracy et. 07 How Women Shaped American Life and Culture Prepared by Susan Sullivan Lagon,Ph.D., Historian, The Jefferson, Washington, DC The Jefferson, Washington, DC • 1200 16th St. NW • Washington DC, 20036 1 The Jefferson, Washington, DC • 1200 16th St. NW • Washington DC, 20036 How Women Shaped American Life and Culture Prepared by Susan Sullivan Lagon, Ph.D., Historian, The Jefferson, Washington, DC John Adams, whose bust is opposite Thomas Jefferson’s in the lobby, was a faithful correspondent with his wife Abigail while she remained in Massachusetts. In a famous letter from Abigail to her husband on March 31, 1776, she wrote: “I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.” Day One Walking Tour From the hotel, head south on 16th St. to Lafayette Square. The large building at H St. and Madison Place is Dolley Madison House. The stately home was built in 1820 by Congressman Richard Cutts who was married to Dolley Madison’s sister Anna. -

In Memoriam Frederick Dougla

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection CANNOT BE PHOTOCOPIED * Not For Circulation Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection / III llllllllllll 3 9077 03100227 5 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection jFrebericfc Bouglass t Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection fry ^tty <y /z^ {.CJ24. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Hn flDemoriam Frederick Douglass ;?v r (f) ^m^JjZ^u To live that freedom, truth and life Might never know eclipse To die, with woman's work and words Aglow upon his lips, To face the foes of human kind Through years of wounds and scars, It is enough ; lead on to find Thy place amid the stars." Mary Lowe Dickinson. PHILADELPHIA: JOHN C YORSTON & CO., Publishers J897 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Copyright. 1897 & CO. JOHN C. YORSTON Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection 73 7^ In WLzmtxtrnm 3fr*r**i]Ch anglais; "I have seen dark hours in my life, and I have seen the darkness gradually disappearing, and the light gradually increasing. One by one, I have seen obstacles removed, errors corrected, prejudices softened, proscriptions relinquished, and my people advancing in all the elements I that make up the sum of general welfare. remember that God reigns in eternity, and that, whatever delays, dis appointments and discouragements may come, truth, justice, liberty and humanity will prevail." Extract from address of Mr. -

Where to Go Camping

There was a statement in an older version of the Boy Scout Handbook that said: “Have you ever dreamed of hiking the wilderness trails that were worn down under moccasins hundreds of years ago? Do you hear in your imagination the almost soundless dip, dip of Indian canoe paddles or the ring of the axe of an early pioneer hewing a home out of the American wilderness? Have you followed with you mind’s eye the covered wagon on the trek across our continent? Yes, it’s fun to be a Boy Scout! It’s fun to go hiking and camping with your best friends…..to swim, to dive, to paddle a canoe, to wield the axe…..to follow in the footsteps of the pioneers who led the way through the wilderness…..to stare into the glowing embers of the campfire and dream of the wonders of the lift that is in store for you…” This is the heart of Scouting, but we don’t always know the best place to go on these outings. How better can the Order of the Arrow fulfill a part of their responsibility of service to others than to make this camping guide available? A great guide to the best camping, boating, hiking and sightseeing both in and out of the Council, but, of course, one of the best places to do real camping is at one of the Council’s reservations. Richard A. Henson or Rodney Scout Reservation, both long term camping during the summer months, or weekends through the year, affords a maximum of program. -

Introduction

Introduction R. J. Ellis One of the most influential books ever written, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly was also one of the most popular in the nineteenth century. Stowe wrote her novel in order to advance the anti-slavery cause in the ante-bellum USA, and rooted her attempt to do this in a ‘moral suasionist’ approach — one designed to persuade her US American compatriots by appealing to their God-given sense of morality. This led to some criticism from immediate abolitionists — who wished to see slavery abolished immediately rather than rely upon [per]suasion. Uncle Tom's Cabin was first published in 1852 as a serial in the abolitionist newspaper National Era . It was then printed in two volumes in Boston by John P. Jewett and Company later in 1852 (with illustrations by Hammatt Billings). The first printing of five thousand copies was exhausted in a few days. Title page, with illustration by Hammatt Billings, Uncle Tom’s Cabin Vol. 1, Boston, John P. Jewett and Co., 1852 During 1852 several reissues were printed from the plates of the first edition; each reprinting also appearing in two volumes, with the addition of the words ‘Tenth’ to ‘One Hundred and Twentieth Thousand’ on the title page, to distinguish between each successive re-issue. Later reprintings of the two-volume original carried even higher numbers. These reprints appeared in various bindings — some editions being quite lavishly bound. One-volume versions also appeared that same year — most of these being pirated editions. From the start the book attracted enormous attention. -

Individual Projects

PROJECTS COMPLETED BY PROLOGUE DC HISTORIANS Mara Cherkasky This Place Has A Voice, Canal Park public art project, consulting historian, http://www.thisplacehasavoice.info The Hotel Harrington: A Witness to Washington DC's History Since 1914 (brochure, 2014) An East-of-the-River View: Anacostia Heritage Trail (Cultural Tourism DC, 2014) Remembering Georgetown's Streetcar Era: The O and P Streets Rehabilitation Project (exhibit panels and booklet documenting the District Department of Transportation's award-winning streetcar and pavement-preservation project, 2013) The Public Service Commission of the District of Columbia: The First 100 Years (exhibit panels and PowerPoint presentations, 2013) Historic Park View: A Walking Tour (booklet, Park View United Neighborhood Coalition, 2012) DC Neighborhood Heritage Trail booklets: Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail (2006); Battleground to Community: Brightwood Heritage Trail (2008); A Self-Reliant People: Greater Deanwood Heritage Trail (2009); Cultural Convergence: Columbia Heights Heritage Trail (2009); Top of the Town: Tenleytown Heritage Trail (2010); Civil War to Civil Rights: Downtown Heritage Trail (2011); Lift Every Voice: Georgia Avenue/Pleasant Plains Heritage Trail (2011); Hub, Home, Heart: H Street NE Heritage Trail (2012); and Make No Little Plans: Federal Triangle Heritage Trail (2012) “Mount Pleasant,” in Washington at Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital (Kathryn Schneider Smith, editor, Johns Hopkins Press, 2010) Mount -

White House U.S

Connecticut Department To Farragut West of Veterans To McPherson Square Metro station Ave Affairs Metro station blue, orange, and silver lines St. John’s blue, orange, and silver lines 16th Street Church Ave Vermont H Street Decatur Von Steuben Kosciuszko House statue statue White House U.S. Court of Historical LAFAYETTE Appeals and Association Baruch U.S. Court Bench of of Claims New Executive Inspiration Jackson Office Building statue White House Conference Pennsylvania Ave PARK Center Treasury Jackson Place Renwick Blair-Lee Rochambeau Lafayette Madison Place Annex Gallery House statue statue New York Ave Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest Northeast Gate Gate Gallatin G Street NORTH LAWN statue G Street To Metro Center Metro station blue, orange, silver, and red lines Dwight D. Eisenhower Department 17th Street Executive Office of the Treasury 15th Street Building White House Liberty Bell Replica F Street F Street East Executive Park West Executive Ave West To SOUTH Octagon Hamilton House statue Pennsylvania Ave State Place Alexander Hamilton North Southwest Southeast Gate Place New York Ave Gate Enter here for tours by SHERMAN reservation only First Division PERSHING PARK Monument Sherman statue To Federal Triangle Corcoran Metro station Gallery of Art LAWN blue, orange, and PARK silver lines E Street E Street Pennsylvania Ave E Street South Butt–Millet Ellipse Visitor American Fountain Pavilion White House Visitor Center National Zero Red Cross Milestone Enter under blue awnings National Christmas Tree D Street Daughters of Boy Scout the American Memorial Revolution ELLIPSE Original Patentees C Street Memorial Department of Commerce Organization of American States Second Division Bulfinch Memorial Bulfinch Gatehouse Gatehouse Haupt Fountains Haupt Fountains To Lincoln and To Smithsonian Vietnam Veterans Institution Memorials Constitution Avenue Lock To World War II, To Washington Monument Keepers F. -

7350 NBM Blueprnts/REV

MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Washington: Symbol and City The name almost succeeds: District of institutions and places of interest that make Columbia. The last word soars. Hail this a world-class city. This exhibition traces Columbia, happy land, the gem of the a range of stories that are fascinating for ocean discovered by the admiral from both the local and the visitor, illuminating Genoa, Cristoforo Colombo, the Admiral the sometimes forgotten connections of the Ocean Seas. But the word district between the heroic and the mundane aspects has all the wrong connotations, as in of the city. water and sewer district or garment dis- The show takes a particular trict or district jail; the term is inherently look at the occasional conflicts that under- local and provincial, devoid of the dignity standably arise from this curious circum- accorded to a state. — from Washington stance. Administered directly by the feder- Itself, by E.J. Applewhite al government for much of its history, the Chase W. Rynd In the first lines of his estimable District of Columbia has at times been a book on Washington, Mr. Applewhite got political pawn. Even today, with a locally right to the heart of the paradox that is the elected mayor and city council, the District nation’s capital. Born of geographical and must constantly negotiate a careful path political compromise, Washington has with Congress and numerous federal agen- always had a split personality. It is a place cies that retain substantial power over the of grand public buildings and elegant neigh- city’s destiny. -

Download Brochure

Enjoy live narration of the underlying history and significance of the top Zohery Tours offers diversified monuments and main attractions. We offer transportation services to suit individual virtual tours of Washington DC (including and corporate needs. If you’re looking the Grand Tour and African American for transportation services in the DC Heritage), Alexandria and Mt. Vernon, and Metro Area, Zohery Tours is your #1 Treasures of Egypt - all at the comfort of choice! your home! Zohery Tours has been helping teachers take their students on personalized educational Tour Departures fieldtrips across the area for over 30 years. Traveling with us will ensure that you travel All tours depart from in safe and comfortable buses, all while having tons of fun. Student safety is our 400 New Jersey Ave NW number one priority. This is why Zohery Tours is a trusted name in student travel. Washington DC 20001 (2 ½ blocks away from the Union Station Metro) CELEBRATING OVER 30 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE IN SIGHTSEEING Lectured Tours and Transportation 202-554-4200 WWW.ZOHERY.COM Email: [email protected] Itinerary of the Daily Tours (excluding the Mount Vernon Tour) DAILY TOURS Grand Tour of Alexandria & Washington Mount Vernon $79 per person $59 per person (Entrance fee included) Departs at 10:30 AM Departs at 2:00 PM Approx. 3-4 hours Approx. 4-5 hours Washington Full Day Tour After Dark $59 per person $138 per person (Entrance fee included) Departs at 7:30 PM Departs at 10:30 AM Approx. 3-4 hours Approx. 8-9 hours Child: $39 (age 3-11) The Full Day Tour is a combination of the Grand Tour and the PRIVATE TOURS Alexandria & Mount Vernon Tour. -

Midcity at the Crossroads: Shaw Heritage Trail

On this self-guided walking Midcity at the Crossroads tour of Shaw, historic markers lead you to: SHAW HERITAGE TRAIL - Home of Carter G. Woodson, originator of Black History Month - Site of former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s high school - “Boss” Shepherd’s tragic mistake - Roots of Arena Stage - Site of the city’s first convention center - Alley life in Washington - Origins of DC’s Jewish Community Centers - Sites of the 1968 riots provoked by the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Shaw, the crossroads neighborhood at the edge of downtown, has been home to the newcomer and the old timer, the powerful and the poor, white and black. Follow this trail to discover Shaw’s scholars, politicians, alley dwellers, activists, barkeeps, merchants, artists, entertainers, and spiritual leaders. Welcome. Visitors to Washington, DC flock to the National Mall, where grand monuments symbolize the nation’s highest ideals. This self-guided walking tour is the sixth in a series that invites you to discover what lies beyond the monuments: Washington’s historic neighborhoods. The Shaw neighborhood you are about to explore is one of the city’s oldest, where traces can be found of nearly every group that has called Washington home. Shaw was partly disfigured by the riots following the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King,Jr.,in. Yet much of its rich past remains for you to see. This guide points you to the legacies of daily life in this Midcity neighborhood between downtown and uptown. Dance class at the YWCA, around 1940. Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University ©2006, Cultural Tourism DC All rights reserved. -

Extensions of Remarks E1755 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

December 10, 2015 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1755 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS MICROBEAD-FREE WATERS ACT OF HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO ESTHER fifty years to the service of our Western New 2015 ORTIZ CARDENAS York community. Mr. Curley was born and raised in Buffalo, SPEECH OF HON. WILL HURD New York. After graduating from Canisius OF TEXAS High School in 1959, where he was first team HON. CAROLYN B. MALONEY IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES all Catholic in tennis, he moved to Boston, where he graduated with an A.B. degree in OF NEW YORK Thursday, December 10, 2015 mathematics from Boston College in 1963. He IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Mr. HURD of Texas. Mr. Speaker, I rise then returned to Buffalo to pursue an M.S. de- today to recognize the 100th birthday of Es- gree from Canisius College. Monday, December 7, 2015 ther Ortiz Cardenas of Del Rio, Texas. He was an instructor at D’Youville and A beloved mother of 12 children, grand- Mrs. CAROLYN B. MALONEY of New York. Canisius Colleges, where he lectured in statis- mother of 29 grandchildren, 48 great-grand- Mr. Speaker, I rise in strong support of the tics, accounting, and business valuation tech- children and 8 great, great grandchildren, Mrs. Microbead-Free Waters Act. niques. Mr. Curley went on to work in banking Cardenas is a woman known for her devout at Marine Midland, before starting his own Microbeads, the small plastic particles con- faith, her hard work and her generous hospi- tained in many face washes and other cleans- business consulting company, St.