Silence: the Reasons Why People May Not Communicate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Social Media and the Spiral of Silence: the Case of Kuwaiti Female Students’ Political Discourse on Twitter

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 16 | Issue 3 Article 4 Jul-2015 Social Media and the Spiral of Silence: The aC se of Kuwaiti Female Students Political Discourse on Twitter Ali A. Dashti Hamed H. Al-Abdullah Hasan A. Johar Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dashti, Ali A.; Al-Abdullah, Hamed H.; and Johar, Hasan A. (2015). Social Media and the Spiral of Silence: The asC e of Kuwaiti Female Students Political Discourse on Twitter. Journal of International Women's Studies, 16(3), 42-53. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol16/iss3/4 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2015 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Social Media and the Spiral of Silence: The Case of Kuwaiti Female Students’ Political Discourse on Twitter By Ali A. Dashti1, Hamed H Al-Abdullah2 and Hasan A Johar3 Abstract The theory of the Spiral of Silence (Noelle-Neumann, 1984), explained why the view of a minority is not presented when the majority view dominates the public sphere. For years the theory of the spiral of silence was used to describe the isolation of minority opinions when seeking help from traditional media, which play a significant role in increasing the isolation. -

The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works Theresa A. Incampo Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Incampo, Theresa A., "The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/209 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical and Sonic Landscapes within the Short Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Submitted by Theresa A. Incampo May 4, 2012 Trinity College Department of Theater and Dance Hartford, CT 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 I: History Time, Space and Sound in Beckett’s short dramatic works 7 A historical analysis of the playwright’s theatrical spaces including the concept of temporality, which is central to the subsequent elements within the physical, metaphysical and sonic landscapes. These landscapes are constructed from physical space, object, light, and sound, so as to create a finite representation of an expansive, infinite world as it is perceived by Beckett’s characters.. II: Theory Phenomenology and the conscious experience of existence 59 The choice to focus on the philosophy of phenomenology centers on the notion that these short dramatic works present the theatrical landscape as the conscious character perceives it to be. The perceptual experience is explained by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as the relationship between the body and the world and the way as to which the self-limited interior space of the mind interacts with the limitless exterior space that surrounds it. -

The Use of Silence As a Political Rhetorical Strategy (TITLE)

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2003 The seU of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy Timothy J. Anderson Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Speech Communication at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Anderson, Timothy J., "The sU e of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy" (2003). Masters Theses. 1434. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1434 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS/FIELD EXPERIENCE PAPER REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library~r research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date thesis4.form The Use of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy (TITLE) BY Timothy J. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

12-96 Shelby County V. Holder (06/25/2013)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2012 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus SHELBY COUNTY, ALABAMA v. HOLDER, ATTORNEY GENERAL, ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT No. 12–96. Argued February 27, 2013—Decided June 25, 2013 The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was enacted to address entrenched racial discrimination in voting, “an insidious and pervasive evil which had been perpetuated in certain parts of our country through unremitting and ingenious defiance of the Constitution.” South Carolina v. Kat- zenbach, 383 U. S. 301, 309. Section 2 of the Act, which bans any “standard, practice, or procedure” that “results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen . to vote on account of race or color,” 42 U. S. C. §1973(a), applies nationwide, is permanent, and is not at issue in this case. Other sections apply only to some parts of the country. Section 4 of the Act provides the “coverage formula,” de- fining the “covered jurisdictions” as States or political subdivisions that maintained tests or devices as prerequisites to voting, and had low voter registration or turnout, in the 1960s and early 1970s. -

Running Head: Social Media and the Spiral of Silence 1

Running Head: Social Media and the Spiral of Silence 1 Social Media and the Spiral of Silence Lauren E. Sale Boston University Author Note: This paper was prepared for Introduction to Emerging Media taught by Dr. Shanahan at the College of Communication Running Head: Social Media and the Spiral of Silence 2 Abstract This paper explores Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann's theory of the Spiral of Silence and it's application to social media. Through out the paper, modern day examples of social or civic issues linked to the Spiral of Silence theory. Furthermore, the paper looks at analyses of Noelle-Neumann's theory in an attempt to look at the modern day relevance of the theory. Keywords: Spiral of Silence, Social Media, Ferguson, opinion expression Running Head: Social Media and the Spiral of Silence 3 Most people have seen these scenarios: 1) A friend's Facebook rant about a current news event that gets dozens of likes, comments, or shares. 2) A Twitter discussion with numerous comments bashing the opinion of the original Tweet. 3) Dozens of Facebook friends suddenly sharing the same opinion on some social or political event. What is the explanation behind these occurrences? In today's hyper-connected world, the expression of opinions is at a high. Social media acts as a strong platform for 'voicing' these opinions. However, it is debatable if social media empowers those with unpopular opinions to share them. In fact, some research indicates that only the dominant opinion can thrive on social media. Introduction Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann's iconic book, The Spiral of Silence, analyzes how people and the climate shape opinion formation and sharing (1984). -

TIMES, BETRAYAL and a KIND of ALASKA PEREIRA, Luís Alberto

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-93132002000100005 MEMORY AS DISCOURSE IN HAROLD PINTER’S OLD LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude. Tristes Trópicos. Lisboa: Edições 70. 2004. TIMES, BETRAYAL AND A KIND OF ALASKA PEREIRA, Luís Alberto. Drama biográfico – “Hans Staden”. Coprodução luso-brasileira. 1999. Carla Ferreira de Castro RIBEIRO, Darcy. O Povo Brasileiro – a formação e o sentido do Brasil. São Universidade de Évora Portugal Paulo: Companhia das Letras. 2.ª Edição. 1995. [email protected] ROUCH, Jean. “Les Maîtres Fous”. Documentário/filme. 1955. Consultado a 15 de Maio de 2012: Abstract http://www.veoh.com/watch/v14179347tanDtaPa?h1=Jean+Rouch+%3 A+Les+ma%C3%AEtres+fous+-+The+mad+masters This paper aims at developing the topic of identity and the narration of SANTIAGO, Silviano. “Mário, Oswald e Carlos, intérpretes do Brasil”. ALCEU – v.5 – n.10 – Jan./Jun. 2005. P.p. 5 – 17. Consultado a 15 de Maio de the self through the other in Harold Pinter’s plays Old Times, Betrayal and A Kind . In these plays Pinter deploys strategies to convey multiple implications 2012: of Alaska which are based on the power of memory in which the structure of the plays is http://revistaalceu.com.puc-rio.br/media/alceu_n10_santiago.pdf concocted. STADEN, Hans. 1520-ca 1565. Viagem ao Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Academia Brasileira, 1930. 186 P. Consultado a 15 de Maio de 2012: http://purl.pt/151 Pinter, Language, Silence, Memory, Time STOLLER, Paul. “Artaud, rouch, and The cinema of Cruelty”. 1992. Key words: Visual Anthropology Review. Volume 8, n. º 2. “Every genuinely important step forward is accompanied by a return to the beginning...more precisely to a renewal of the beginning. -

Breaking the Wall of Silence Practitioners’ Responses to Trafficked Children and Young People

Breaking the wall of silence Practitioners’ responses to trafficked children and young people Jenny J. Pearce, Patricia Hynes and Silvie Bovarnick June 2009 www.nspcc.org.uk/inform Pearce, J.J., Hynes, P. and Bovarnick, S. Breaking the wall of silence Acknowledgements We would like to thank all those who contributed time to this research project by participating in the focus groups and interviews as well as allowing access to case information. Past and present members of the advisory group played an invaluable role in supporting, inspiring and steering this research through to its conclusion. Members are or have been Silvie Bovarnick (NSPCC Fresh Start), Sue Bradshaw (ACPO), Wendy DuChesne (BIA), Jane Dykins (Refugee Council), Sarah Field (University of Bedfordshire), Zoe Hilton (NSPCC), Patricia Hynes (NSPCC Fresh Start), Mandy John-Baptiste (NSPCC National Child Trafficking Advice and Information Line, NSPCC Fresh Start), Aarti Kapoor (CEOP), Susanne McGregor (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine), Andrea Marie (NSPCC), David McDonald (Home Office), Louise Moore (DCSF), Amanda Palmer (UKHTC), Nasima Patel (NSPCC), Nicola Payne (UKBA), Jenny Pearce (University of Bedfordshire), Jo Phoenix (Durham University), Victoria Presland (UKBA) and Lorraine Radford (NSPCC). Particular acknowledgements are given to the range of staff at the three research sites. Their time, effort and support have been invaluable. Many thanks go to the NSPCC National Child Trafficking Advice and Information Line (CTAIL) Young Persons Advisory Group who provided insightful feedback on the findings to the research team. Others who have provided crucial assistance include Heaven Crawley (University of Swansea) and Nadine Finch (Garden Court Chambers). We would also like to acknowledge Margaret Melrose (University of Bedfordshire) for her work on this project and Wendy Roberts (Fresh Start, NSPCC) for her idea of a “road map” in gaining disclosure from children and young people who have been trafficked. -

Review Title Review Rating Created Date

CoEnzyme Q-10 200mg Rating and review summary as of 07/09/19 from HSN website Review Title Review Rating Created_Date June Easy to swallow capsules ,i being feeling much 5 7/7/2019 4:51:42 PM more healthy since taking this product.My blood flow in my legs has improved no more numbness.. IT WORKS! Taking the Q10 helped reduce my cholesterol. 5 7/7/2019 1:11:26 PM Love this product Andrew Lessman Co q-10 is a wonderful 5 6/16/2019 5:57:04 AM product. I am a repeat customer and have ordered other products from Andrew Lessman and love each and every one of them. This Co Q10 far exceeds any product over the counter in any store. Will be buying again and again. Good product I have taken this for years and can't say I feel a 5 6/14/2019 2:46:54 PM difference. I now have my husband taking it because of his statin med. I do feel it helps us in ways we don't realize and I believe what Andrew says about the benefits of taking it. He has alot of knowledge and because of his research and interest in making people's health better. Thank you Andrew. CoRnzyme Q 10 with 200 of vitamin D I love coEnzyme Q 10 200 w Vit D this product 5 4/26/2019 3:39:11 PM gives me energy for my day. Also love it with Vit B. Andrew please continue to bring this to Us Use every day This and the Omega 3 are very important to 5 4/23/2019 6:33:17 PM take. -

Dreams-041015 1.Pdf

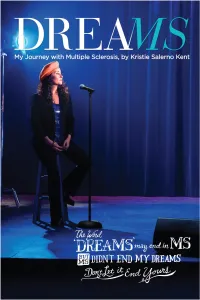

DREAMS My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis By Kristie Salerno Kent DREAMS: MY JOURNEY WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. Copyright © 2013 by Acorda Therapeutics®, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Author’s Note I always dreamed of a career in the entertainment industry until a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis changed my life. Rather than give up on my dream, following my diagnosis I decided to fight back and follow my passion. Songwriting and performance helped me find the strength to face my challenges and help others understand the impact of MS. “Dreams: My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis,” is an intimate and honest story of how, as people living with MS, we can continue to pursue our passion and use it to overcome denial and find the courage to take action to fight MS. It is also a story of how a serious health challenge does not mean you should let go of your plans for the future. The word 'dreams' may end in ‘MS,’ but MS doesn’t have to end your dreams. It has taken an extraordinary team effort to share my story with you. This book is dedicated to my greatest blessings - my children, Kingston and Giabella. You have filled mommy's heart with so much love, pride and joy and have made my ultimate dream come true! To my husband Michael - thank you for being my umbrella during the rainy days until the sun came out again and we could bask in its glow together. Each end of our rainbow has two pots of gold… our precious son and our beautiful daughter! To my heavenly Father, thank you for the gifts you have blessed me with.