Bohmian Mechanics and the Quantum Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Lattice Structure of Quantum Logic

BULL. AUSTRAL. MATH. SOC. MOS 8106, *8IOI, 0242 VOL. I (1969), 333-340 On the lattice structure of quantum logic P. D. Finch A weak logical structure is defined as a set of boolean propositional logics in which one can define common operations of negation and implication. The set union of the boolean components of a weak logical structure is a logic of propositions which is an orthocomplemented poset, where orthocomplementation is interpreted as negation and the partial order as implication. It is shown that if one can define on this logic an operation of logical conjunction which has certain plausible properties, then the logic has the structure of an orthomodular lattice. Conversely, if the logic is an orthomodular lattice then the conjunction operation may be defined on it. 1. Introduction The axiomatic development of non-relativistic quantum mechanics leads to a quantum logic which has the structure of an orthomodular poset. Such a structure can be derived from physical considerations in a number of ways, for example, as in Gunson [7], Mackey [77], Piron [72], Varadarajan [73] and Zierler [74]. Mackey [77] has given heuristic arguments indicating that this quantum logic is, in fact, not just a poset but a lattice and that, in particular, it is isomorphic to the lattice of closed subspaces of a separable infinite dimensional Hilbert space. If one assumes that the quantum logic does have the structure of a lattice, and not just that of a poset, it is not difficult to ascertain what sort of further assumptions lead to a "coordinatisation" of the logic as the lattice of closed subspaces of Hilbert space, details will be found in Jauch [8], Piron [72], Varadarajan [73] and Zierler [74], Received 13 May 1969. -

Relational Quantum Mechanics

Relational Quantum Mechanics Matteo Smerlak† September 17, 2006 †Ecole normale sup´erieure de Lyon, F-69364 Lyon, EU E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this internship report, we present Carlo Rovelli’s relational interpretation of quantum mechanics, focusing on its historical and conceptual roots. A critical analysis of the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen argument is then put forward, which suggests that the phenomenon of ‘quantum non-locality’ is an artifact of the orthodox interpretation, and not a physical effect. A speculative discussion of the potential import of the relational view for quantum-logic is finally proposed. Figure 0.1: Composition X, W. Kandinski (1939) 1 Acknowledgements Beyond its strictly scientific value, this Master 1 internship has been rich of encounters. Let me express hereupon my gratitude to the great people I have met. First, and foremost, I want to thank Carlo Rovelli1 for his warm welcome in Marseille, and for the unexpected trust he showed me during these six months. Thanks to his rare openness, I have had the opportunity to humbly but truly take part in active research and, what is more, to glimpse the vivid landscape of scientific creativity. One more thing: I have an immense respect for Carlo’s plainness, unaltered in spite of his renown achievements in physics. I am very grateful to Antony Valentini2, who invited me, together with Frank Hellmann, to the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, in Canada. We spent there an incredible week, meeting world-class physicists such as Lee Smolin, Jeffrey Bub or John Baez, and enthusiastic postdocs such as Etera Livine or Simone Speziale. -

Why Feynman Path Integration?

Journal of Uncertain Systems Vol.5, No.x, pp.xx-xx, 2011 Online at: www.jus.org.uk Why Feynman Path Integration? Jaime Nava1;∗, Juan Ferret2, Vladik Kreinovich1, Gloria Berumen1, Sandra Griffin1, and Edgar Padilla1 1Department of Computer Science, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA 2Department of Philosophy, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA Received 19 December 2009; Revised 23 February 2010 Abstract To describe physics properly, we need to take into account quantum effects. Thus, for every non- quantum physical theory, we must come up with an appropriate quantum theory. A traditional approach is to replace all the scalars in the classical description of this theory by the corresponding operators. The problem with the above approach is that due to non-commutativity of the quantum operators, two math- ematically equivalent formulations of the classical theory can lead to different (non-equivalent) quantum theories. An alternative quantization approach that directly transforms the non-quantum action functional into the appropriate quantum theory, was indeed proposed by the Nobelist Richard Feynman, under the name of path integration. Feynman path integration is not just a foundational idea, it is actually an efficient computing tool (Feynman diagrams). From the pragmatic viewpoint, Feynman path integral is a great success. However, from the founda- tional viewpoint, we still face an important question: why the Feynman's path integration formula? In this paper, we provide a natural explanation for Feynman's path integration formula. ⃝c 2010 World Academic Press, UK. All rights reserved. Keywords: Feynman path integration, independence, foundations of quantum physics 1 Why Feynman Path Integration: Formulation of the Problem Need for quantization. -

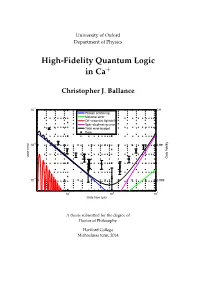

High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+

University of Oxford Department of Physics High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+ Christopher J. Ballance −1 10 0.9 Photon scattering Motional error Off−resonant lightshift Spin−dephasing error Total error budget Data −2 10 0.99 Gate error Gate fidelity −3 10 0.999 1 2 3 10 10 10 Gate time (µs) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Hertford College Michaelmas term, 2014 Abstract High-Fidelity Quantum Logic in Ca+ Christopher J. Ballance A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Michaelmas term 2014 Hertford College, Oxford Trapped atomic ions are one of the most promising systems for building a quantum computer – all of the fundamental operations needed to build a quan- tum computer have been demonstrated in such systems. The challenge now is to understand and reduce the operation errors to below the ‘fault-tolerant thresh- old’ (the level below which quantum error correction works), and to scale up the current few-qubit experiments to many qubits. This thesis describes experimen- tal work concentrated primarily on the first of these challenges. We demonstrate high-fidelity single-qubit and two-qubit (entangling) gates with errors at or be- low the fault-tolerant threshold. We also implement an entangling gate between two different species of ions, a tool which may be useful for certain scalable architectures. We study the speed/fidelity trade-off for a two-qubit phase gate implemented in 43Ca+ hyperfine trapped-ion qubits. We develop an error model which de- scribes the fundamental and technical imperfections / limitations that contribute to the measured gate error. -

![Arxiv:2002.00255V3 [Quant-Ph] 13 Feb 2021 Lem (BVP)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0853/arxiv-2002-00255v3-quant-ph-13-feb-2021-lem-bvp-370853.webp)

Arxiv:2002.00255V3 [Quant-Ph] 13 Feb 2021 Lem (BVP)

A Path Integral approach to Quantum Fluid Dynamics Sagnik Ghosh Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune-411008, India Swapan K Ghosh UM-DAE Centre for Excellence in Basic Sciences, University of Mumbai, Kalina, Santacruz, Mumbai-400098, India ∗ (Dated: February 16, 2021) In this work we develop an alternative approach for solution of Quantum Trajectories using the Path Integral method. The state-of-the-art technique in the field is to solve a set of non-linear, coupled partial differential equations (PDEs) simultaneously. We opt for a fundamentally different route. We first derive a general closed form expression for the Path Integral propagator valid for any general potential as a functional of the corresponding classical path. The method is exact and is applicable in many dimensions as well as multi-particle cases. This, then, is used to compute the Quantum Potential (QP), which, in turn, can generate the Quantum Trajectories. For cases, where closed form solution is not possible, the problem is formally boiled down to solving the classical path as a boundary value problem. The work formally bridges the Path Integral approach with Quantum Fluid Dynamics. As a model application to illustrate the method, we work out a toy model viz. the double-well potential, where the boundary value problem for the classical path has been computed perturbatively, but the Quantum part is left exact. Using this we delve into seeking insight in one of the long standing debates with regard to Quantum Tunneling. Keywords: Path Integral, Quantum Fluid Dynamics, Analytical Solution, Quantum Potential, Quantum Tunneling, Quantum Trajectories Submitted to: J. -

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit

Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamics in a Classical Transmon Circuit Sasu Tuohino B. Sc. Thesis Department of Physical Sciences Theoretical Physics University of Oulu 2017 Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Classical network theory4 2.1 From electromagnetic fields to circuit elements.........4 2.2 Generalized flux and charge....................6 2.3 Node variables as degrees of freedom...............7 3 Hamiltonians for electric circuits8 3.1 LC Circuit and DC voltage source................8 3.2 Cooper-Pair Box.......................... 10 3.2.1 Josephson junction.................... 10 3.2.2 Dynamics of the Cooper-pair box............. 11 3.3 Transmon qubit.......................... 12 3.3.1 Cavity resonator...................... 12 3.3.2 Shunt capacitance CB .................. 12 3.3.3 Transmon Lagrangian................... 13 3.3.4 Matrix notation in the Legendre transformation..... 14 3.3.5 Hamiltonian of transmon................. 15 4 Classical dynamics of transmon qubit 16 4.1 Equations of motion for transmon................ 16 4.1.1 Relations with voltages.................. 17 4.1.2 Shunt resistances..................... 17 4.1.3 Linearized Josephson inductance............. 18 4.1.4 Relation with currents................... 18 4.2 Control and read-out signals................... 18 4.2.1 Transmission line model.................. 18 4.2.2 Equations of motion for coupled transmission line.... 20 4.3 Quantum notation......................... 22 5 Numerical solutions for equations of motion 23 5.1 Design parameters of the transmon................ 23 5.2 Resonance shift at nonlinear regime............... 24 6 Conclusions 27 1 Abstract The focus of this thesis is on classical dynamics of a transmon qubit. First we introduce the basic concepts of the classical circuit analysis and use this knowledge to derive the Lagrangians and Hamiltonians of an LC circuit, a Cooper-pair box, and ultimately we derive Hamiltonian for a transmon qubit. -

Theoretical Physics Group Decoherent Histories Approach: a Quantum Description of Closed Systems

Theoretical Physics Group Department of Physics Decoherent Histories Approach: A Quantum Description of Closed Systems Author: Supervisor: Pak To Cheung Prof. Jonathan J. Halliwell CID: 01830314 A thesis submitted for the degree of MSc Quantum Fields and Fundamental Forces Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Mathematical Formalism9 2.1 General Idea...................................9 2.2 Operator Formulation............................. 10 2.3 Path Integral Formulation........................... 18 3 Interpretation 20 3.1 Decoherent Family............................... 20 3.1a. Logical Conclusions........................... 20 3.1b. Probabilities of Histories........................ 21 3.1c. Causality Paradox........................... 22 3.1d. Approximate Decoherence....................... 24 3.2 Incompatible Sets................................ 25 3.2a. Contradictory Conclusions....................... 25 3.2b. Logic................................... 28 3.2c. Single-Family Rule........................... 30 3.3 Quasiclassical Domains............................. 32 3.4 Many History Interpretation.......................... 34 3.5 Unknown Set Interpretation.......................... 36 4 Applications 36 4.1 EPR Paradox.................................. 36 4.2 Hydrodynamic Variables............................ 41 4.3 Arrival Time Problem............................. 43 4.4 Quantum Fields and Quantum Cosmology.................. 45 5 Summary 48 6 References 51 Appendices 56 A Boolean Algebra 56 B Derivation of Path Integral Method From Operator -

Are Non-Boolean Event Structures the Precedence Or Consequence of Quantum Probability?

Are Non-Boolean Event Structures the Precedence or Consequence of Quantum Probability? Christopher A. Fuchs1 and Blake C. Stacey1 1Physics Department, University of Massachusetts Boston (Dated: December 24, 2019) In the last five years of his life Itamar Pitowsky developed the idea that the formal structure of quantum theory should be thought of as a Bayesian probability theory adapted to the empirical situation that Nature’s events just so happen to conform to a non-Boolean algebra. QBism too takes a Bayesian stance on the probabilities of quantum theory, but its probabilities are the personal degrees of belief a sufficiently- schooled agent holds for the consequences of her actions on the external world. Thus QBism has two levels of the personal where the Pitowskyan view has one. The differences go further. Most important for the technical side of both views is the quantum mechanical Born Rule, but in the Pitowskyan development it is a theorem, not a postulate, arising in the way of Gleason from the primary empirical assumption of a non-Boolean algebra. QBism on the other hand strives to develop a way to think of the Born Rule in a pre-algebraic setting, so that it itself may be taken as the primary empirical statement of the theory. In other words, the hope in QBism is that, suitably understood, the Born Rule is quantum theory’s most fundamental postulate, with the Hilbert space formalism (along with its perceived connection to a non-Boolean event structure) arising only secondarily. This paper will avail of Pitowsky’s program, along with its extensions in the work of Jeffrey Bub and William Demopoulos, to better explicate QBism’s aims and goals. -

Simulation of the Bell Inequality Violation Based on Quantum Steering Concept Mohsen Ruzbehani

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Simulation of the Bell inequality violation based on quantum steering concept Mohsen Ruzbehani Violation of Bell’s inequality in experiments shows that predictions of local realistic models disagree with those of quantum mechanics. However, despite the quantum mechanics formalism, there are debates on how does it happen in nature. In this paper by use of a model of polarizers that obeys the Malus’ law and quantum steering concept, i.e. superluminal infuence of the states of entangled pairs to each other, simulation of phenomena is presented. The given model, as it is intended to be, is extremely simple without using mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics. However, the result completely agrees with prediction of quantum mechanics. Although it may seem trivial, this model can be applied to simulate the behavior of other not easy to analytically evaluate efects, such as defciency of detectors and polarizers, diferent value of photons in each run and so on. For example, it is demonstrated, when detector efciency is 83% the S factor of CHSH inequality will be 2, which completely agrees with famous detector efciency limit calculated analytically. Also, it is shown in one-channel polarizers the polarization of absorbed photons, should change to the perpendicular of polarizer angle, at very end, to have perfect violation of the Bell inequality (2 √2 ) otherwise maximum violation will be limited to (1.5 √2). More than a half-century afer celebrated Bell inequality 1, nonlocality is almost totally accepted concept which has been proved by numerous experiments. Although there is no doubt about validity of the mathematical model proposed by Bell to examine the principle of the locality, it is comprehended that Bell’s inequality in its original form is not testable. -

Violation of Bell Inequalities: Mapping the Conceptual Implications

International Journal of Quantum Foundations 7 (2021) 47-78 Original Paper Violation of Bell Inequalities: Mapping the Conceptual Implications Brian Drummond Edinburgh, Scotland. E-mail: [email protected] Received: 10 April 2021 / Accepted: 14 June 2021 / Published: 30 June 2021 Abstract: This short article concentrates on the conceptual aspects of the violation of Bell inequalities, and acts as a map to the 265 cited references. The article outlines (a) relevant characteristics of quantum mechanics, such as statistical balance and entanglement, (b) the thinking that led to the derivation of the original Bell inequality, and (c) the range of claimed implications, including realism, locality and others which attract less attention. The main conclusion is that violation of Bell inequalities appears to have some implications for the nature of physical reality, but that none of these are definite. The violations constrain possible prequantum (underlying) theories, but do not rule out the possibility that such theories might reconcile at least one understanding of locality and realism to quantum mechanical predictions. Violation might reflect, at least partly, failure to acknowledge the contextuality of quantum mechanics, or that data from different probability spaces have been inappropriately combined. Many claims that there are definite implications reflect one or more of (i) imprecise non-mathematical language, (ii) assumptions inappropriate in quantum mechanics, (iii) inadequate treatment of measurement statistics and (iv) underlying philosophical assumptions. Keywords: Bell inequalities; statistical balance; entanglement; realism; locality; prequantum theories; contextuality; probability space; conceptual; philosophical International Journal of Quantum Foundations 7 (2021) 48 1. Introduction and Overview (Area Mapped and Mapping Methods) Concepts are an important part of physics [1, § 2][2][3, § 1.2][4, § 1][5, p. -

Quantum Nonlocality Explained

Quantum Nonlocality Explained Ulrich Mohrhoff Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education Pondicherry 605002 India [email protected] Abstract Quantum theory's violation of remote outcome independence is as- sessed in the context of a novel interpretation of the theory, in which the unavoidable distinction between the classical and quantum domains is understood as a distinction between the manifested world and its manifestation. 1 Preliminaries There are at least nine formulations of quantum mechanics [1], among them Heisenberg's matrix formulation, Schr¨odinger'swave-function formu- lation, Feynman's path-integral formulation, Wigner's phase-space formula- tion, and the density-matrix formulation. The idiosyncracies of these forma- tions have much in common with the inertial reference frames of relativistic physics: anything that is not invariant under Lorentz transformations is a feature of whichever language we use to describe the physical world rather than an objective feature of the physical world. By the same token, any- thing that depends on the particular formulation of quantum mechanics is a feature of whichever mathematical tool we use to calculate the values of observables or the probabilities of measurement outcomes rather than an objective feature of the physical world. That said, when it comes to addressing specific questions, some formu- lations are obviously more suitable than others. As Styer et al. [1] wrote, The ever-popular wavefunction formulation is standard for prob- lem solving, but leaves the conceptual misimpression that [the] wavefunction is a physical entity rather than a mathematical tool. The path integral formulation is physically appealing and 1 generalizes readily beyond the domain of nonrelativistic quan- tum mechanics, but is laborious in most standard applications. -

Quantum Simulation of the Single-Particle Schrodinger Equation

Quantum simulation of the single-particle Schr¨odinger equation 1,2, 3, Giuliano Benenti ∗ and Giuliano Strini † 1CNISM, CNR-INFM & Center for Nonlinear and Complex Systems, Universit`adegli Studi dell’Insubria, Via Valleggio 11, 22100 Como, Italy 2Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Milano, via Celoria 16, 20133 Milano, Italy 3Dipartimento di Fisica, Universit`adegli Studi di Milano, Via Celoria 16, 20133 Milano, Italy (Dated: May 21, 2018) The working of a quantum computer is described in the concrete example of a quantum simulator of the single-particle Schr¨odinger equation. We show that a register of 6 − 10 qubits is sufficient to realize a useful quantum simulator capable of solving in an efficient way standard quantum mechanical problems. I. INTRODUCTION II. QUANTUM LOGIC 1,2 The elementary unit of quantum information is the During the last years quantum information has be- qubit (the quantum counterpart of the classical bit) and come one of the new hot topic field in physics, with the a quantum computer may be viewed as a many-qubit potential to revolutionize many areas of science and tech- system. Physically, a qubit is a two-level system, like nology. Quantum information replaces the laws of classi- 1 the two spin states of a spin- 2 particle, the polarization cal physics, applied to computation and communication, states of a single photon or two states of an atom. with the more fundamental laws of quantum mechanics. A classical bit is a system that can exist in two dis- This becomes increasingly important due to technological tinct states, which are used to represent 0 and 1, that progress reaching smaller and smaller scales.