Beethoven No. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

A Formal Analytical Approach Was Utilized to Develop Chart Analyses Of

^ DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 970 24 HE 000 764 .By-Hanson, John R. Form in Selected Twentieth-Century Piano Concertos. Final Report. Carroll Coll., Waukesha, Wis. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureauof Research. Bureau No-BR-7-E-157 Pub Date Nov 68 Crant OEC -0 -8 -000157-1803(010) Note-60p. EDRS Price tvw-s,ctso HC-$3.10 Descriptors-Charts, Educational Facilities, *Higher Education, *Music,*Music Techniques, Research A formal analytical approach was utilized to developchart analyses of all movements within 33 selected piano concertoscomposed in the twentieth century. The macroform, or overall structure, of each movement wasdetermined by the initial statement, frequency of use, andorder of each main thematic elementidentified. Theme groupings were then classified underformal classical prototypes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (ternary,sonata-allegro, 5-part or 7-part rondo, theme and variations, and others), modified versionsof these forms (three-part design), or a variety of free sectionalforms. The chart and thematic illustrations are followed by a commentary discussing each movement aswell as the entire concerto. No correlation exists between styles andforms of the 33 concertos--the 26 composers usetraditional,individualistic,classical,and dissonant formsina combination of ways. Almost all works contain commonunifying thematic elements, and cyclicism (identical theme occurring in more than1 movement) is used to a great degree. None of the movements in sonata-allegroform contain double expositions, but 22 concertos have 3 movements, and21 have cadenzas, suggesting that the composers havelargely respected standards established in theClassical-Romantic period. Appendix A is the complete form diagramof Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Appendix B has concentrated analyses of all the concertos,and Appendix C lists each movement accordog to its design.(WM) DE:802 FINAL REPORT Project No. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

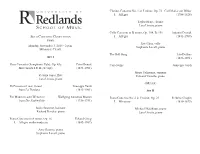

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart – Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Mozart entered this concerto in his catalog on February 10, 1785, and performed the solo in the premiere the next day in Vienna. The orchestra consists of one flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. At these concerts, Shai Wosner plays Beethoven’s cadenza in the first movement and his own cadenza in the finale. Performance time is approximately thirty-four minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20 were given at Orchestra Hall on January 14 and 15, 1916, with Ossip Gabrilowitsch as soloist and Frederick Stock conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on March 15, 16, and 17, 2007, with Mitsuko Uchida conducting from the keyboard. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 6, 1961, with John Browning as soloist and Josef Krips conducting, and most recently on July 8, 2007, with Jonathan Biss as soloist and James Conlon conducting. This is the Mozart piano concerto that Beethoven admired above all others. It’s the only one he played in public (and the only one for which he wrote cadenzas). Throughout the nineteenth century, it was the sole concerto by Mozart that was regularly performed—its demonic power and dark beauty spoke to musicians who had been raised on Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt. -

Chicago Presents Symphony Muti Symphony Center

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI zell music director SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS 17 cso.org1 312-294-30008 1 STIRRING welcome I have always believed that the arts embody our civilization’s highest ideals and have the power to change society. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a leading example of this, for while it is made of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians— PERFORMANCES. each individually skilled in his or her instrument—we achieve the greatest impact working together as one: as an orchestra or, in other words, as a community. Our purpose is to create the utmost form of artistic expression and in so doing, to serve as an example of what we can achieve as a collective when guided by our principles. Your presence is vital to supporting that process as well as building a vibrant future for this great cultural institution. With that in mind, I invite you to deepen your relationship with THE music and with the CSO during the 2017/18 season. SOUL-RENEWING Riccardo Muti POWER table of contents 4 season highlight 36 Symphony Center Presents Series Riccardo Muti & the Chicago Symphony Orchestra OF MUSIC. 36 Chamber Music 8 season highlight 37 Visiting Orchestras Dazzling Stars 38 Piano 44 Jazz 10 season highlight Symphonic Masterworks 40 MusicNOW 20th anniversary season 12 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Series 41 season highlight 34 CSO at Wheaton College John Williams Returns 41 CSO at the Movies Holiday Concerts 42 CSO Family Matinees/Once Upon a Symphony® 43 Special Concerts 13 season highlight 44 Muti Conducts Rossini Stabat mater 47 CSO Media and Sponsors 17 season highlight Bernstein at 100 24 How to Renew Guide center insert 19 season highlight 24 Season Grid & Calendar center fold-out A Tchaikovsky Celebration 23 season highlight Mahler 5 & 9 24 season highlight Symphony Ball NIGHT 27 season highlight Riccardo Muti & Yo-Yo Ma 29 season highlight AFTER The CSO’s Own 35 season highlight NIGHT. -

A B C a B C D a B C D A

24 go symphonyorchestra chica symphony centerpresent BALL SYMPHONY anne-sophie mutter muti riccardo orchestra symphony chicago 22 september friday, highlight season tchaikovsky mozart 7:00 6:00 Mozart’s fiery undisputed queen ofviolin-playing” ( and Tchaikovsky’s in beloved masterpieces, including Rossini’s followed by Riccardo Muti leading the Chicago SymphonyOrchestra season. Enjoy afestive opento the preconcert 2017/18 reception, proudly presents aprestigious gala evening ofmusic and celebration The Board Women’s ofthe Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Gala package guests will enjoy postconcert dinner and dancing. rossini Suite from Suite 5 No. Concerto Violin to Overture C P s oncert reconcert Reception Turkish The Sleeping Beauty Concerto. The SleepingBeauty William Tell conducto The Times . Anne-Sophie Mutter, “the (Turkish) William Tell , London), performs London), , media sponsor: r violin Overture 10 Concerts 10 Concerts A B C A B 5 Concerts 5 Concerts D E F G H I 8 Concerts 5 Concerts E F G H 5 Concerts 6 Conc. 5 Concerts THU FRI FRI SAT SAT SUN TUE 8:00 1:30 8:00 2017/18 8:00 8:00 3:00 7:30 ABCABCD ABCDAAB Riccardo Muti conductor penderecki The Awakening of Jacob 9/23 9/26 Anne-Sophie Mutter violin tchaikovsky Violin Concerto schumann Symphony No. 2 C A 9/28 9/29 Riccardo Muti conductor rossini Overture to William Tell 10/1 ogonek New Work world premiere, cso commission A • F A bruckner Symphony No. 4 (Romantic) A Alain Altinoglu conductor prokoFIEV Suite from The Love for Three Oranges Sandrine Piau soprano poulenc Gloria Michael Schade tenor gounod Saint Cecilia Mass 10/5 10/6 Andrew Foster-Williams 10/7 C • E B bass-baritone B • G Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe chorus director 10/26 10/27 James Gaffigan conductor bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront James Ehnes violin barber Violin Concerto B • I A rachmaninov Symphonic Dances Sir András Schiff conductor mozart Serenade for Winds in C Minor 11/2 11/3 and piano bartók Divertimento for String Orchestra 11/4 11/5 A • G C bach Keyboard Concerto No. -

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao's Piano Concerto, Op. 53

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao’s Piano Concerto, Op. 53: A Comparison with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lin-Min Chang, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Anna Gowboy Dr. Kia-Hui Tan Copyright by Lin-Min Chang 2018 2 ABSTRACT One of the most prominent Taiwanese composers, Tyzen Hsiao, is known as the “Sergei Rachmaninoff of Taiwan.” The primary purpose of this document is to compare and discuss his Piano Concerto Op. 53, from a performer’s perspective, with the Second Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Hsiao’s preferences of musical materials such as harmony, texture, and rhythmic patterns are influenced by Romantic, Impressionist, and 20th century musicians incorporating these elements together with Taiwanese folk song into a unique musical style. This document consists of four chapters. The first chapter introduces Hsiao’s biography and his musical style; the second chapter focuses on analyzing Hsiao’s Piano Concerto Op. 53 in C minor from a performer’s perspective; the third chapter is a comparison of Hsiao and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos regarding the similarities of orchestration and structure, rhythm and technique, phrasing and articulation, harmony and texture. The chapter also covers the differences in the function of the cadenza, and the interaction between solo piano and orchestra; and the final chapter provides some performance suggestions to the practical issues in regard to phrasing, voicing, technique, color, pedaling, and articulation of Hsiao’s Piano Concerto from the perspective of a pianist. -

A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels Achareeya Fukiat Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Fukiat, Achareeya, "A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels" (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5630. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5630 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF SELECTED PIANO CONCERTI FOR ELEMENTARY, INTERMEDIATE, AND EARLY-ADVANCED LEVELS Achareeya Fukiat A Doctoral Research Project submitted to College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance James Miltenberger, -

Univeristy of California Santa Cruz Cultural Memory And

UNIVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CULTURAL MEMORY AND COLLECTIVITY IN MUSIC FROM THE 1991 PERSIAN GULF WAR A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by Jessica Rose Loranger December 2015 The Dissertation of Jessica Rose Loranger is approved: ______________________________ Professor Leta E. Miller, chair ______________________________ Professor Amy C. Beal ______________________________ Professor Ben Leeds Carson ______________________________ Professor Dard Neuman ______________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Jessica Rose Loranger 2015 CONTENTS Illustrations vi Musical Examples vii Tables viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Purpose Literature, Theoretical Framework, and Terminology Scope and Limitations CHAPTER 2: BACKGROUND AND BUILDUP TO THE PERSIAN GULF WAR 15 Historical Roots Desert Shield and Desert Storm The Rhetoric of Collective Memory Remembering Vietnam The Antiwar Movement Conclusion CHAPTER 3: POPULAR MUSIC, POPULAR MEMORY 56 PART I “The Desert Ain’t Vietnam” “From a Distance” iii George Michael and Styx Creating Camaraderie: Patriotism, Country Music, and Group Singing PART II Ice-T and Lollapalooza Michael Franti Ani DiFranco Bad Religion Fugazi Conclusion CHAPTER 4: PERSIAN GULF WAR SONG COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 116 Yellow Ribbons: Symbols and Symptoms of Cultural Memory Parents and Children The American Way Hussein and Hitler Antiwar/Peace Songs Collective -

Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter's 'Self-Reinvention' and the Early

Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter’s ‘Self-Reinvention’ and the Early Cold War Daniel Guberman A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved By, Brigid Cohen, chair Allen Anderson Annegret Fauser Mark Katz Severine Neff © 2012 Daniel Guberman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT DANIEL GUBERMAN: Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter’s ‘Self-Reinvention’ and the Early Cold War (Under the direction of Brigid Cohen) In this dissertation I examine Elliott Carter’s development from the end of the Second World War through the 1960s arguing that he carefully constructed his postwar compositional identity for Cold War audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. The majority of studies of Carter’s music have focused on technical aspects of his methods, or roots of his thoughts in earlier philosophies. Making use of published writings, correspondence, recordings of lectures, compositional sketches, and a drafts of writings, this is one of the first studies to examine Carter’s music from the perspective of the contemporary cultural and political environment. In this Cold War environment Carter emerged as one of the most prominent composers in the United States and Europe. I argue that Carter’s success lay in part due to his extraordinary acumen for developing a public persona. And his presentation of his works resonated with the times, appealing simultaneously to concert audiences, government and private foundation agents, and music professionals including impresarios, performers and other composers. -

R Obert Schum Ann's Piano Concerto in AM Inor, Op. 54

Order Number 0S0T795 Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 54: A stemmatic analysis of the sources Kang, Mahn-Hee, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 U MI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 ROBERT SCHUMANN S PIANO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, OP. 54: A STEMMATIC ANALYSIS OF THE SOURCES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mahn-Hee Kang, B.M., M.M., M.M. The Ohio State University 1992 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Lois Rosow Charles Atkinson - Adviser Burdette Green School of Music Copyright by Mahn-Hee Kang 1992 In Memory of Malcolm Frager (1935-1991) 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the late Malcolm Frager, who not only enthusiastically encouraged me In my research but also gave me access to source materials that were otherwise unavailable or hard to find. He gave me an original exemplar of Carl Relnecke's edition of the concerto, and provided me with photocopies of Schumann's autograph manuscript, the wind parts from the first printed edition, and Clara Schumann's "Instructive edition." Mr. Frager. who was the first to publish information on the textual content of the autograph manuscript, made It possible for me to use his discoveries as a foundation for further research. I am deeply grateful to him for giving me this opportunity. I express sincere appreciation to my adviser Dr. Lois Rosow for her patience, understanding, guidance, and insight throughout the research.