PANNETT, D. (2008). the Ice Age Legacy in North Shropshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download a Leaflet with a Description of the Walk and A

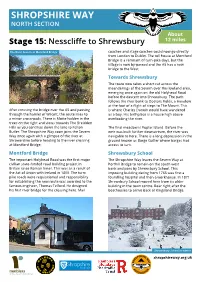

SHROPSHIRE WAY NORTH SECTION About Stage 15: Nesscliffe to Shrewsbury 12 miles The River Severn at Montford Bridge coaches and stage coaches could now go directly from London to Dublin. The toll house at Montford Bridge is a remnant of turn-pike days, but the village is now by-passed and the A5 has a new bridge to the West. Towards Shrewsbury The route now takes a short cut across the meanderings of the Severn over this lowland area, emerging once again on the old Holyhead Road before the descent into Shrewsbury. The path follows the river bank to Doctors Fields, a meadow at the foot of a flight of steps to The Mount. This After crossing the bridge over the A5 and passing is where Charles Darwin would have wandered through the hamlet of Wilcott, the route rises to as a boy. His birthplace is a house high above a minor crossroads. There is Motte hidden in the overlooking the river. trees on the right and views towards The Breidden Hills as you continue down the lane to Felton The final meadow is Poplar Island. Before the Butler. The Shropshire Way soon joins the Severn weir was built further downstream, the river was Way once again with a glimpse of the river at navigable to here. There is a long depression in the Shrawardine before heading to the river crossing ground known as Barge Gutter where barges had at Montford Bridge. access to turn. Montford Bridge Shrewsbury School The important Holyhead Road was the first major The Shropshire Way leaves the Severn Way at civilian state-funded road building project in Porthill Bridge to remain on the south-west Britain since Roman times. -

Special Symposium Edition the Ground Beneath Our Feet: 200 Years of Geology in the Marches

NEWSLETTER August 2007 Special Symposium Edition The ground beneath our feet: 200 years of geology in the Marches A Symposium to be held on Thursday 13th September 2007 at Ludlow Assembly Rooms Hosted by the Shropshire Geological Society in association with the West Midlands Regional Group of the Geological Society of London To celebrate a number of anniversaries of significance to the geology of the Marches: the 200th anniversary of the Geological Society of London the 175th anniversary of Murchison's epic visit to the area that led to publication of The Silurian System. the 150th anniversary of the Geologists' Association The Norton Gallery in Ludlow Museum, Castle Square, includes a display of material relating to Murchison's visits to the area in the 1830s. Other Shropshire Geological Society news on pages 22-24 1 Contents Some Words of Welcome . 3 Symposium Programme . 4 Abstracts and Biographical Details Welcome Address: Prof Michael Rosenbaum . .6 Marches Geology for All: Dr Peter Toghill . .7 Local character shaped by landscapes: Dr David Lloyd MBE . .9 From the Ground, Up: Andrew Jenkinson . .10 Palaeogeography of the Lower Palaeozoic: Dr Robin Cocks OBE . .10 The Silurian “Herefordshire Konservat-Largerstatte”: Prof David Siveter . .11 Geology in the Community:Harriett Baldwin and Philip Dunne MP . .13 Geological pioneers in the Marches: Prof Hugh Torrens . .14 Challenges for the geoscientist: Prof Rod Stevens . .15 Reflection on the life of Dr Peter Cross . .15 The Ice Age legacy in North Shropshire: David Pannett . .16 The Ice Age in the Marches: Herefordshire: Dr Andrew Richards . .17 Future avenues of research in the Welsh Borderland: Prof John Dewey FRS . -

Draft Bridgnorth Area Tourism Strategy and Action Plan

Draft Bridgnorth Area Tourism Strategy and Action Plan For Consultation May 2013 Prepared by the Research and Intelligence Team at Shropshire Council Draft Bridgnorth Area Tourism Strategy and Action Plan Research & Intelligence, Shropshire Council 1 Introduction In March 2013, the Shropshire Council visitor economy team commissioned the Shropshire Council Research and Intelligence unit to prepare a visitor economy strategy and action plan for the Bridgnorth area destination. The strategy and action plan are being prepared by: • Reviewing a variety of published material, including policy documents, research and promotional literature. • Consultation with the following in order to refine the findings of this review: • Bridgnorth and District Tourist Association • Shropshire Star Attractions • Local media (Shropshire Review, What’s What etc) • Virtual Shropshire • Visit Ironbridge • Shropshire Council – councillors and officers • Telford and Wrekin Council • Other neighbouring authorities (Worcestershire, Wyre Forest) • Town and Parish Councils • Town and Parish Plan groups • Local interest groups (historical societies or others with relevance) • Shropshire Tourism • Shropshire Hills and Ludlow Destination Partnership • Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust • Principal attractions and accommodation providers • Major events and activities We would welcome your contribution to this consultation. To complete our consultation form on‐line, please follow: http://www.surveymonkey.com/s/VT9TYMD Alternatively, please address your comments to Tim King, -

Ironbridge Interactive

Telford 15 min drive IRONBRIDGE Born to roam Discover one of Britain’s most exciting and powerful SEVERN GORGE SHROPSHIRE COUNTRYSIDE TRUST destinations, a place that inspired the modern world RAFT TOURS and sparked the industrial revolution. Welcome to the Ironbridge Gorge, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which Woodside attracts millions of visitors each year. Bursting with award- BLISTS HILL winning culture, heritage and the River Severn flowing VICTORIAN TOWN Madeley through artisan attractions, Ironbridge has a lot to offer. THE FURNACE, Click the icons below to find out more about some of the COALBROOKDALE great places you can visit while you are here. We look MERRYTHOUGHT LTD MUSEUM OF IRON forward to welcoming you. ENGLISH HERITAGE Coalbrookdale THE IRON BRIDGE WATERSIDE PUBS SHROPSHIRE WAY & & RESTAURANTS SEVERN VALLEY WAY BLISTS HILL SHROPSHIRE THE MUSEUM OF VICTORIAN TOWN RAFT TOURS THE GORGE MAWS CRAFT CENTRE MERRYTHOUGHT Ironbridge LT D & CREATIVE SPACES River Sev ern ENGLISH HERITAGE SEVERN GORGE COUNTRYSIDE TRUST SHROPSHIRE WAY & THE IRON BRIDGE SEVERN VALLEY WAY THE FURNACE, JACKFIELDTHESEVERNMAWSSHROPSHIREENGLISHMERRYTHOUGHTBLISTS MUSEUMFURNACE, CRAFT HILL GORGE HERITAGE TILE VICTORIAN WAYRAFT CENTREOF COALBROOKDALE COUNTRYSIDEMUSEUM THE LTD AND TOURS THE GORGE & SEVERN TOWNCREATIVEIRON BRIDGE TRUSTVALLEY SPACES WAY COALBROOKDALE MUSEUM OF IRON MUSEUM OF IRON JACKFIELD TILE JackfieldTheExploreIronbridgeMerrythoughtShropshireCommandingAt Blists River Hillthe Severn GorgeGorge wasVictorianRaft forests, the isonce Tours one -

Bridgnorth to Ironbridge to Bridgnorth

Leaflet Ref. No: NCN2D/July 2013 © Shropshire Council July 2013 July Council Shropshire © 2013 NCN2D/July No: Ref. Leaflet Designed by Salisbury SHROPSHIRE yarrington ltd, www.yarrington.co.uk © Shropshire CouncilJuly2013 ©Shropshire yarrington ltd,www.yarrington.co.uk Stonehenge Marlborough Part funded by the Department for Transport for Department the by funded Part 0845 113 0065 113 0845 www.wiltshire.gov.uk www.wiltshire.gov.uk % 01225 713404 01225 Swindon www.sustrans.org.uk www.sustrans.org.uk Wiltshire Council Wiltshire call: or visit Supporter, a become to how and Sustrans For more information on routes in your area, or more about about more or area, your in routes on information more For gov.uk/cycling by the charity Sustrans. charity the by Cirencester www.gloucestershire. This route is part of the National Cycle Network, coordinated coordinated Network, Cycle National the of part is route This % 01452 425000 01452 National Cycle Network Cycle National County Council County Gloucestershire Gloucestershire Gloucester PDF format from our website. our from format PDF All leaflets are available to download in in download to available are leaflets All 253008 01743 gov.uk/cms/cycling.aspx www.worcestershire. Shropshire Council Council Shropshire Worcester % 01906 765765 01906 ©Rosemary Winnall ©Rosemary www.travelshropshire.co.uk County Council County Worcestershire Worcestershire Bewdley www.telford.gov.uk % 01952 380000 380000 01952 Council Telford & Wrekin Wrekin & Telford Bridgnorth co.uk www.travelshropshire. Bridgnorth to Ironbridge -

Ton Constantine, Shrewsbury, SY5 6RD

3 Lower Longwood Cottages, Eaton Constantine, Shrewsbury, SY5 6RD 3 Lower Longwood Cottages a semi- detached property situated just outside Eaton Constantine with stunning views of the landscape. It has two bedrooms, one reception room, kitchen and bathroom. Externally there is large lawned garden and off-road parking. The property is available to let now. Viewings by appointment with the Estate Office only and can be conducted in person or by video. Semi- Detached Off Road Parking Two Bedrooms Available immediately One Reception Room Large Garden To Let: £695 per Calendar Month reasons unconnected with the above, then your Situation and Amenities holding deposit will be returned within 7 days. Market Town of Shrewsbury 8 miles. New Town of Telford 10 miles. The Wrekin part of Insurance Shropshire Hills AONB 6 miles. Christ Church C Tenants are required to insure their own of E Primary, Cressage 3.5 miles. Buildwas contents. Academy 5 miles. Village shops within 5 miles and Shrewsbury and Telford offer supermarkets Smoking and chain stores. Wellington Train Station 8 Smoking is prohibited inside the property. miles, M54 motorway junction 5 miles. Please note all distances are approximate. Pets Pets shall not be kept at the property without the Description prior written consent of the landlord. All requests 3 Lower Longwood Cottages is a two bedroom will be considered and will be subject to separate semi-detached property with accommodation rental negotiation. briefly comprising of; Ground floor an entrance hallway, Bathroom including shower cubicle, Council Tax sink, heated towel rail and vinyl flooring, Kitchen For Council Tax purposes the property is banded which includes fitted wall and base units with B within the Shropshire County Council fitted worktops, tiled splashbacks, stainless steel authority. -

Analysis of 2008 CPA the Scale of Things

Analysis of 2008 CPA The Scale of Things Councillor Newton Wood Chair Overview and Scrutiny 23 JULY 2008 1 FOREWORD The contents of this report have the approval of the Overview and Scrutiny Coordinating Group for presentation to the full Overview and Scrutiny Committee meeting for their consideration on Wednesday 23 rd July 2008. It is important that this report identifies, for officers, members and the community, the exact position Teesdale is in, that is in relation to the scale of performance within our own county, County Durham and in the bigger picture that is in the country as a whole. Without being aware of where we are, we are unlikely to know where we are going! Unitary status is on the horizon. Durham County Council is a 4 star authority and has compared itself to other single tier councils in the country. Beyond doubt, with such expertise, acknowledged skills and professionalism the new authority will serve to compliment and improve upon the quality of services for the Teesdale community. However, as many weaknesses have been identified by the 2008 CPA inspection, our position in relation to the rest of the country has already been determined by The Audit Commission. This report highlights:- • Where we are at this point in time • Areas which need attention • Those weaknesses which can be handed over to county methods and procedures. • Some areas which need urgent attention by Teesdale District Council • The new county councillors representing Teesdale will now, hopefully, be aware of where we are in the scale of things and the work they have ahead of them to bring us in line with our fellow districts in County Durham. -

B4380 Buildwas Speed Management Feasibility Report March 2017

B4380 Buildwas Speed Management Feasibility Report March 2017 Report Reference: 1076162 Prepared by: 2nd Floor, Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2 Site Description .................................................................................................... 2 3 Site Observations...………………….………………………………………………..…5 4 Personal Injury Collision (PIC) and Speed data…….……………………………..... 7 5 Conclusions and Recommendations..…………………………………………..……..8 Version Date Detail Prepared By Checked By Approved By March Issue Feasibility Report D Ross D Davies PF Williams 2017 This Report is presented to Shropshire Council in respect of the B4380 Buildwas Speed Management Feasibility Study and may not be used or relied on by any other person or by the client in relation to any other matters not covered specifically by the scope of this Report. Notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained in the report, Mouchel Limited is obliged to exercise reasonable skill, care and diligence in the performance of the services required by Shropshire Council and Mouchel Limited shall not be liable except to the extent that it has failed to exercise reasonable skill, care and diligence, and this report shall be read and construed accordingly. This report has been prepared by Mouchel Limited. No individual is personally liable in connection with the preparation of this Report. By receiving this Report and acting on it, the client or any other person accepts that no individual is personally liable whether in contract, tort, for breach of statutory duty or otherwise. 2 B4380 Buildwas Speed Management March 2017 1 Introduction 1.1 Buildwas village is situated on the B4380 road (between Shrewsbury and Ironbridge) close to its junction with the A4169 Ironbridge Bypass. -

2001 Census Report for Parliamentary Constituencies

Reference maps Page England and Wales North East: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 42 North West: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 43 Yorkshire & The Humber: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 44 East Midlands: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 45 West Midlands: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 46 East of England: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 47 London: County & Parliamentary Constituencies 48 South East: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 49 South West: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 50 Wales: Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies 51 Scotland Scotland: Scottish Parliamentary Regions 52 Central Scotland Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 53 Glasgow Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 54 Highlands and Islands Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 55 Lothians Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 56 Mid Scotland and Fife Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 57 North East Scotland Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 58 South of Scotland Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 59 West of Scotland Region: Parliamentary Constituencies 60 Northern Ireland Northern Ireland: Parliamentary Constituencies 61 41 Reference maps Census 2001: Report for Parliamentary Constituencies North East: Counties, Unitary Authorities & Parliamentary Constituencies Key government office region parliamentary constituencies counties -

History Notes Tileries, Caughley to Coalport Walks

Caughley China Works Broseley Tileries In 1772 Thomas Turner of Worcester came to Caughley Tile making in Broseley goes back along way, A 'tyle house' (kiln) was mentioned along with Ambrose Gallimore, a Staffordshire potter, as being on ‘priory land’ in 1545. High quality local clays were mined alongside to extend a factory that had been in existence there for coal and iron and by the C19th, and as cities grew there was a huge market for about 15 years. Known as the Salopian Porcelain bricks, roof and floor tiles. Said to have been established in 1760, in operation Manufactory the Caughley works made some of the from at least 1828, by 1838 the Broseley Tileries were the largest works in the finest examples of C18th English Porcelain, now highly Broseley and Jackfield area. By 1870 the firm produced tessellated and encaustic sought after by collectors. Turner used underglaze floor tiles as well as roof and plain floor tiles. Broseley Tileries were operated by printing to make tea and dessert sets and other wares. the Onions family until 1877 when they sold them to a new company, Broseley Printing from copperplate engravings enabled designs Tileries Co Ltd. Another works close by was the Dunge Brick and Tile Works , it to be mass produced at low cost by a ceramic transfer ceased manufacture in 1903. In 1889 the area's leading manufacturers of roof Look for the monument at process, alongside the expensive hand painted the site of the Caughley tiles, which for some years had been known by the generic name 'Broseley Tiles', porcelain. -

Shropshire Way Festival of Walks Programme 18-25 September 2021

Shropshire Way Festival of Walks Programme 18-25 September 2021 PLEASE BOOK A PLACE IN ADVANCE. SOME WALKS HAVE LIMITED NUMBERS PLEASE WEAR APPROPRIATE CLOTHING AND FOOTWEAR AND BRING REFRESHMENTS AS NECESSARY. PLEASE NO DOGS EVERY EFFORT WILL BE MADE TO POST ANY LAST MINUTE CHANGES TO WALKS ON THE WEBSITE shropshireway.org.uk Organising Walk Group / Walk Walk Details Booking Information / Further Details No Leader Saturday 18 September A varied 8.5 mile ramble with 1150 feet of ascent amidst the wild and rolling countryside of south west Shropshire. The route visits the southern section of the Stiperstones then heads west to Love The Hills, 1 Mucklewick Hill and Flenny Bank before Contact the walk leader, Marshall Cale, 07484 868323 Marshall Cale returning via the hamlet of Tankerville. A mix of rocky paths, tracks and quiet country lanes with mostly easy ascents. Fabulous views and points of interest. Meet 10:00 at The Bog car park SJ355979 A 9.5 mile circular walk from Craven Arms Railway Station following the Shropshire Way to Stokesay Court and returning to Craven Arms via Whettleton Rail Rambles, Nigel Hill, Nortoncamp Wood and Whettleton. From 10:00 Sunday 12 September visit the website 2 Hotchkiss & John If travelling to and from Shrewsbury https://www.railrambles.org/programme/ Mattocks Railway Station, bus replaces train departing 09:15 and returns from Craven Arms at 16:25. Otherwise meet at Craven Arms Railway Station for walk start at 10:10 A 12.5 mile walk to Little Wenlock, mainly by the Telford T50, then part of the Little Wenlock bench walks to the Wellington Walkers lunch stop by the pool in Little Wenlock. -

Think Property, Think Savills

Telford Open Gardens PRINT.indd 1 PRINT.indd Gardens Open Telford 01/12/2014 16:04 01/12/2014 www.shropshirehct.org.uk www.shropshirehct.org.uk out: Check savills.co.uk Registered Charity No. 1010690 No. Charity Registered [email protected] Email: 2020 01588 640797 01588 Tel. Pam / 205967 07970 Tel. Jenny Contact: [email protected] 01952 239 532 239 01952 group or on your own, all welcome! all own, your on or group Beccy Theodore-Jones Beccy to raise funds for the SHCT. As a a As SHCT. the for funds raise to [email protected] Please join us walking and cycling cycling and walking us join Please 01952 239 500 239 01952 Ride+Stride, 12 September, 2020: 2020: September, 12 Ride+Stride, ony Morris-Eyton ony T 01746 764094 01746 operty please contact: please operty r p a selling or / Tel. Tel. / [email protected] Email: Dudley Caroline from obtained If you would like advice on buying buying on advice like would you If The Trust welcomes new members and membership forms can be be can forms membership and members new welcomes Trust The 01743 367166 01743 Tel. / [email protected] very much like to hear from you. Please contact: Angela Hughes Hughes Angela contact: Please you. from hear to like much very If you would like to offer your Garden for the scheme we would would we scheme the for Garden your offer to like would you If divided equally between the Trust and the parish church. parish the and Trust the between equally divided which offers a wide range of interesting gardens, the proceeds proceeds the gardens, interesting of range wide a offers which One of the ways the Trust raises funds is the Gardens Open scheme scheme Open Gardens the is funds raises Trust the ways the of One have awarded over £1,000,000 to Shropshire churches.