Not About Madonna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

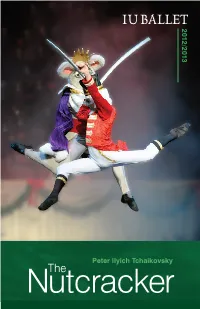

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

Syntactic Variations of African-American Vernacular English (Aave) Employed by the Main Character in Hustle & Flow

SYNTACTIC VARIATIONS OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN VERNACULAR ENGLISH (AAVE) EMPLOYED BY THE MAIN CHARACTER IN HUSTLE & FLOW A THESIS Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Attainment of a Sarjana Sastra Degree in English Language & Literature By: DESTYANA PRASTITASARI 07211144026 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE STUDY PROGRAM ENGLISH EDUCATION DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS YOGYAKARTA STATE UNIVERSITY 2013 MOTTOS Stay focus, work very hard, and do your best. (Farah Quinn) There’s no reason to say ‘I cannot do it’ because ‘I can do it’ I can get the tired and desperate feelings but they cannot occur in more than 24 hours Always smile, greet for everyone, and everything gonna be alright (Mottos of my life) Everybody gotta have a dream (Hustle & Flow) v DEDICATIONS I dedicate this thesis to: My beloved mama (Mrs.Bingartin), My papa (Mr.Sumarno) who always give me love , pray, support and deep understanding, My beloved sweetheart, who always gives me spirit and patience, and My younger brother Ardhi ‘Hwang Kichu’ who always supports and accompanies me in writing this thesis. vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Alhamdulillah, all praise be to Allah SWT, the Almighty, the Most Gracious and the Most Merciful, without which I would never have finished this thesis. In accomplishing this thesis, I owe to many people for the support, guidance, assistance, and help. I would like to express my deepest gratitude and thanks to RA Rahmi Dipayanti Andayani, M.Pd., my first consultant and Titik Sudartinah, M.A., my second consultant, for their endless support, advice, patience and great guidance in helping me throughout this thesis. -

Danc Scapes Choreographers 2015

dancE scapes Choreographers 2015 Amy Cain was born in Jacksonville, Florida and grew up in The Woodlands/Spring area of Texas. Her 30+ years of dance training include working with various instructors and choreographers nationwide and abroad. She has also been coached privately and been inspired for most of her dance career by Ken McCulloch, co-owner of NHPA™. Amy is in her 22nd year of partnership in directing NHPA™, named one of the “Top 50 Studios On the Move” by Dance Teacher Magazine in 2006, and has also been co-director of Revolve Dance Company for 10 years. She also shares her teaching experience as a jazz instructor for the upper level students at Houston Ballet Academy. Amy has danced professionally with Ad Deum, DWDT, and Amy Ell’s Vault, and her choreographic works have been presented in Italy, Mexico, and at many Houston area events. In June 2014 Amy’s piece “Angsters”, performed by Revolve Dance Company, was presented as a short film produced by Gothic South Productions at the Dance Camera estW Festival in L.A. where it received the “Audience Favorite” award. This fall “Angsters” will be screened on Opening Night at the San Francisco Dance Film Festival in California, and on the first screening weekend at the Sans Souci Festival of Dance Cinema in Boulder, Colorado. Dawn Dippel (co-owner) has been dancing most of her life and is now co-owner of NHPA™, co-Director and founding member of Revolve Dance Company, and a former member of the Dominic Walsh Dance Theatre. She grew up in the Houston area, graduated from Houston’s High School for the Performing & Visual Arts Dance Department, and since then has been training in and outside of Houston. -

Friday Night Cypher Lyrics – Big Sean Feat. Eminem | Funmeloud

Friday Night Cypher Lyrics – Big Sean Feat. Eminem | FunMeLoud Friday Night Cypher Lyrics – Big Sean : At almost a ten-minute run-time, this collaboration brings together rappers with very different styles, as well as individuals who have previously had disagreements – notablyEminem and Tee Grizzley, which Big Sean addressed in an interview with Vulture: Song : Friday Night Cypher Artist : Big Sean : Kash Doll, Payroll Giovanni, Royce da 5’9″, Sada Featuring Baby, Drego, Boldy James, 42 Dugg, Eminem, Cash Kidd & Tee Grizzley Produced by : KeY Wane, Jay John Henry, Helluva Beats & Hit-Boy Album : Detroit 2 Friday Night Cypher Lyrics [Intro: Tee Grizzley] Ayy, ayy, ayy Ayy, ayy, ayy (Hit-Boy) Ayy, this that Clipse sample, ayy Fuck that talkin’, let the clip slam ’em [Verse 1: Tee Grizzley] Friday Night Cypher Lyrics Yellow bands around them hundreds, you know how much that is (Tens) Too much to give me cash, they had to wire me the backend (Send it) Niggas in here lookin’ tough, you know that I got mag in (What?) Ask me am I only rappin’, you know I got that bag in (You see it) Bandman like Lonnie (Lonnie), want my head? Come find me (Come get it) Lil’ bro in that bitch chillin’, he ain’t tryna come home cocky (He chillin’) He comin’ home to a dollar (Dollar), and a mansion and a chopper (What else?) In the desert on a dirt bike (Skrrt), VLONE shirt and the Pradas (Fresh) Big nigga fresher than you, fuck you and your stylist (Woah) Paid ninety for my grill, then lost it, that’s why I ain’t smilin’ (Damn) You got Sean, you got Hit, you got -

The Soraya Joins Martha Graham Dance Company and Wild up for the June 19 World Premiere of a Digital Dance Creation

The Soraya Joins Martha Graham Dance Company and Wild Up for the June 19 World Premiere of a Digital Dance Creation Immediate Tragedy Inspired by Martha Graham’s lost solo from 1937, this reimagined version will feature 14 dancers and include new music composed by Wild Up’s Christopher Rountree (New York, NY), May 28, 2020—The ongoing collaboration by three major arts organizations— Martha Graham Dance Company, the Los Angeles-based Wild Up music collective, and The Soraya—will continue June 19 with the premiere of a digital dance inspired by archival remnants of Martha Graham’s Immediate Tragedy, a solo she created in 1937 in response to the Spanish Civil War. Graham created the solo in collaboration with composer Henry Cowell, but it was never filmed and has been considered lost for decades. Drawing on the common experience of today’s immediate tragedy – the global pandemic -- the 22 artists creating the project are collaborating from locations across the U.S. and Europe using a variety of technologies to coordinate movement, music, and digital design. The new digital Immediate Tragedy, commissioned by The Soraya, will premiere online Friday, June 19 at 4pm (Pacific)/7pm (EST) during Fridays at 4 on The Soraya Facebook page, and Saturday, June 20 at 11:30am/2:30pm at the Martha Matinee on the Graham Company’s YouTube Channel. In its new iteration, Immediate Tragedy will feature 14 dancers and 6 musicians each recorded from the safety of their homes. Martha Graham Dance Company’s Artistic Director Janet Eilber, in consultation with Rountree and The Soraya’s Executive Director, Thor Steingraber, suggested the long-distance creative process inspired by a cache of recently rediscovered materials—over 30 photos, musical notations, letters and reviews all relating to the 1937 solo. -

Dance, American Dance

DA CONSTAANTLYN EVOLVINGCE TRADITION AD CONSTAANTLY NEVOLVINGCE TRADITION BY OCTAVIO ROCA here is no time like the Michael Smuin’s jazzy abandon, in present to look at the future of Broadway’s newfound love of dance, American dance. So much in every daring bit of performance art keeps coming, so much is left that tries to redefine what dance is behind, and the uncertainty and what it is not. American dancers Tand immense promise of all that lies today represent the finest, most ahead tell us that the young century exciting, and most diverse aspects of is witnessing a watershed in our country’s cultural riches. American dance history. Candid The phenomenal aspect of dance is shots of American artists on the that it takes two to give meaning to move reveal a wide-open landscape the phenomenon. The meaning of a of dance, from classical to modern dance arises not in a vacuum but in to postmodern and beyond. public, in real life, in the magical Each of our dance traditions moment when an audience witnesses carries a distinctive flavor, and each a performance. What makes demands attention: the living American dance unique is not just its legacies of George Balanchine and A poster advertises the appearance of New distinctive, multicultural mix of Antony Tudor, the ever-surprising York City Ballet as part of Festival Verdi influences, but also the distinctively 2001 in Parma, Italy. genius of Merce Cunningham, the American mix of its audiences. That all-American exuberance of Paul Taylor, the social mix is even more of a melting pot as the new commitment of Bill T. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Megan Thee Stallion : Good News | No.1 Lyrics Bros

Go Crazy Lyrics – Megan Thee Stallion : Good News | No.1 Lyrics Bros Go Crazy Lyrics – Megan Thee Stallion : Good News : “Go Crazy” is a track with high volume backtalk and character. With Megan Thee Stallion putting her weave up to give these girls a beating, this was sure to be a classy hit. Song : Go Crazy Artist : Megan Thee Stallion Featuring : Big Sean & 2 Chainz Produced by : Nicki Pooyandeh, Benjamin Lasnier & J.R. Rotem Album : Good News Go Crazy Lyrics Megan Thee Stallion [Intro: Megan Thee Stallion] Yeah Ah Real hot girl shit Mwah Go Crazy Lyrics [Verse 1: Megan Thee Stallion] Okay, the hate turned me to a monster, so I guess I’m evil now (I’m evil now) Woke up and I blacked out everything so I can see it now (See it now) I’m on that demon time, it’s only right I cop the Hellcat (Skrrt) They always hit me where it hurt, but this time, I felt that (Ow) Why I gotta prove myself to bitches that I’m better than? (Huh?) As if I wasn’t at radio stations goin’ Super Saiyan (Super Saiyan) As if this fuckin’ body isn’t everything they buyin’ (‘Thing they buyin’) And as if a nigga didn’t shoot me and they pickin’ sides (Baow) [Chorus: Megan Thee Stallion] Go Crazy Lyrics I’ll be back, I’m ’bout to go crazy I ain’t pullin’ up ‘less them hoes finna pay me (‘Less them hoes finna pay me) Bitch, I’m the shit, and I ain’t gotta prove it (I ain’t gotta prove it) Finna go dumb since these hoes think I’m stupid I’m ’bout to go crazy, crazy I’m ’bout to go crazy, crazy Bitch, I’m ’bout to go [Verse 2: Big Sean] I hit once, I hit twice, now it’s -

Graham 2 2019 New York Season May 30–June 2, 2019

Graham 2 2019 New York Season May 30–June 2, 2019 New York, NY, May 1, 2019 – Graham 2 announces its 2019 New York season featuring works by Martha Graham and a world premiere by guest choreographer Brice Mousset. Performances are May 30–June 2 (Thursday through Saturday at 7pm, and Sunday at 3pm), at the Martha Graham Studio Theater, 55 Bethune Street, 11th floor, in Manhattan. Graham 2 Director Virginie Mécène has selected a program reflecting on the Martha Graham Dance Company’s season theme, The Eve Project, which explores the many facets of womanhood. Performed by Graham 2’s exceedingly talented young dancers, the program provides ways to consider Graham’s complex, multifaceted characters through dances that evoke innocence, seduction, erotic love, empowerment, rejection, resilience, and more. The program will feature Heretic (1929), excerpts from Embattled Garden (1958) and El Penitente (1940), Conversation of Lovers from Acts of Light (1981), Appalachian Spring Suite (1944), the newly revived Secular Games (1962), and a new work by French choreographer Brice Mousset, set to the music of composer Mike Sheridan. The opening night on May 30 will be a special night for Graham 2 alumni. The troupe is now 36 years old, and the performance will include media featuring many generations of Graham 2 dancers. General tickets are $25 in advance, $30 at the door. Students $15 in advance/$20 at the door. Special alumni ticket price: $20 in advance/$25 at the door. Tickets can be purchased online at marthagraham.org/graham2. About choreographer Brice Mousset Brice Mousset is founder, artistic director, and choreographer of OUI DANSE, a New York City project-based dance company. -

Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age.” I Am Grateful This Is the First 2020 Issue JHHS Is Publishing

Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Travis Harris Managing Editor Shanté Paradigm Smalls, St. John’s University Associate Editors: Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, Georgia State University Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Willie "Pops" Hudson, Azusa Pacific University Javon Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Elliot Powell, University of Minnesota Books and Media Editor Marcus J. Smalls, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Conference and Academic Hip Hop Editor Ashley N. Payne, Missouri State University Poetry Editor Jeffrey Coleman, St. Mary's College of Maryland Global Editor Sameena Eidoo, Independent Scholar Copy Editor: Sabine Kim, The University of Mainz Reviewer Board: Edmund Adjapong, Seton Hall University Janee Burkhalter, Saint Joseph's University Rosalyn Davis, Indiana University Kokomo Piper Carter, Arts and Culture Organizer and Hip Hop Activist Todd Craig, Medgar Evers College Aisha Durham, University of South Florida Regina Duthely, University of Puget Sound Leah Gaines, San Jose State University Journal of Hip Hop Studies 2 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/1 2 Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Elizabeth Gillman, Florida State University Kyra Guant, University at Albany Tasha Iglesias, University of California, Riverside Andre Johnson, University of Memphis David J. Leonard, Washington State University Heidi R. Lewis, Colorado College Kyle Mays, University of California, Los Angeles Anthony Nocella II, Salt Lake Community College Mich Nyawalo, Shawnee State University RaShelle R. -

ASSOCIATION for JEWISH STUDIES 37TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Hilton Washington, Washington, DC December 18–20, 2005

ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES 37TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Hilton Washington, Washington, DC December 18–20, 2005 Saturday, December 17, 2005, 8:00 PM Farragut WORKS IN PROGRESS GROUP IN MODERN JEWISH STUDIES Co-chairs: Leah Hochman (University of Florida) Adam B. Shear (University of Pittsburgh) Sunday, December 18, 2005 GENERAL BREAKFAST 8:00 AM – 9:30 AM International Ballroom East (Note: By pre-paid reservation only.) REGISTRATION 8:30 AM – 6:00 PM Concourse Foyer AJS ANNUAL BUSINESS MEETING 8:30 AM – 9:30 AM Lincoln East AJS BOARD OF 10:30 AM Cabinet DIRECTORS MEETING BOOK EXHIBIT (List of Exhibitors p. 63) 1:00 PM – 6:30 PM Exhibit Hall Session 1, Sunday, December 18, 2005 9:30 AM – 11:00 AM 1.1 Th oroughbred INSECURITIES AND UNCERTAINTIES IN CONTEMPORARY JEWISH LIFE Chair and Respondent: Leonard Saxe (Brandeis University) Eisav sonei et Ya’akov?: Setting a Historical Context for Catholic- Jewish Relations Forty Years after Nostra Aetate Jerome A. Chanes (Brandeis University) Judeophobia and the New European Extremism: La trahison des clercs 2000–2005 Barry A. Kosmin (Trinity College) Living on the Edge: Understanding Israeli-Jewish Existential Uncertainty Uriel Abulof (Th e Hebrew University of Jerusalem) 1.2 Monroe East JEWISH MUSIC AND DANCE IN THE MODERN ERA: INTERSECTIONS AND DIVERGENCES Chair and Respondent: Hasia R. Diner (New York University) Searching for Sephardic Dance and a Fitting Accompaniment: A Historical and Personal Account Judith Brin Ingber (University of Minnesota) Dancing Jewish Identity in Post–World War II America: -

Joe's Cozy Powell Collection

Joe’s Cozy Powell Collection Cozy POWELL singles Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {UK}<7”> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {UK / Belgium}<export 7”, p/s (1), orange lettering> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {UK / Belgium}<export blue vinyl 7”, p/s (1), orange / white lettering> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {UK / Denmark}<export 7”, different p/s (2)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Germany}<7”, different p/s (3)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Holland}<7”, different p/s (4)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Holland}<7”, reissue, different p/s (5)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {EEC}<7”, Holland different p/s (6)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Mexico}<7”, different p/s (7)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Spain}<7”, different p/s (8)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Italy}<7”, different p/s (9)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {France}<7”, different p/s (10)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Turkey}<7”, different p/s (11)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Yugoslavia}<7”, different p/s (12)> Dance With The Drums / And Then There Was Skin {South Africa}<7”> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Ireland}<7”> Dance With The Devil [mono] / Dance With The Devil [stereo] {USA}<promo 7”> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {USA}<7”> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Sweden}<7”> Dance With The