The World of Apu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48P

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48p. Rs.30 It Is the famous rhymes collection of Bengali Literature. 2. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 60p. Rs.30 It in the most popular Bengala Rhymes ener written. 3. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Dey's 1990; 48p. Rs.10 It is the most famous rhyme collection of Bengali Literature. 4. Aachin Paakhi Dutta, Asit : Nikhil Bharat Shishu Sahitya 2002; 48p. Rs.30 Eight-stories, all bordering on humour by a popular writer. 5. Aadhikar ke kake dei Mukhophaya, Sutapa Kolkata: A 'N' E Publishers 1999; 28p. Rs.16 8185136637 This book intend to inform readers on their Rights and how to get it. 6. Aagun - Pakhir Rahasya Gangopadhyay, Sunil Kolkata: Ananda Publishers 1996; 119p. Rs.30 8172153198 It is one of the most famous detective story and compilation of other fun stories. 7. Aajgubi Galpo Bardhan, Adrish (ed.) : Orient Longman 1989; 117p. Rs.12 861319699 A volume on interesting and detective stories of Adrish Bardhan. 8. Aamar banabas Chakraborty, Amrendra : Swarnakhar Prakashani 1993; 24p. Rs.12 It is nice poetry for childrens written by Amarendra Chakraborty. 9. Aamar boi Mitra, Premendra : Orient Longman 1988; 40p. Rs.6 861318080 Amar Boi is a famous Primer-cum-beginners book written by Premendra Mitra. 10. Aat Rahasya Phukan, Bandita New Delhi: Fantastic ; 168p. Rs.27 This is a collection of eight humour A Mystery Stories. 12. Aatbhuture Mitra, Khagendranath Kolkata: Ashok Prakashan 1996; 140p. Rs.25 A collection of defective stories pull of wonder & surprise. 13. Abak Jalpan lakshmaner shaktishel jhalapala Ray, Kumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 58p. -

APARAJITO (THE UNVANQUISHED) 1956 Satyajit Ray

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. APARAJITO (THE UNVANQUISHED) 1956 Satyajit Ray Bengali language OVERVIEW Aparajito is the second part of the Apu trilogy, based on the novels by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay. The first part (Pather Panchali) concludes with Apu (aged about six or seven) and his parents leaving their village in Bengal. This second part traces the story of Apu’s growth from a school boy to young man at college in Calcutta (with two different actors playing him in those two stages of life). Since his father dies early on, the core of the story is the heart-rending relationship between Apu and his mother. As with Pather Panchali, there is pathos with two key deaths, but there is also hope for Apu’s future. The movie is structured in three sections, moving from the city to the village and back to the city, and each one represents a crucial stage in the development of Apu as a young man. CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE Within India, Aparajito did not achieve the same success as the first section of the trilogy (Pather Panchali). One reason for this was that Ray deliberately darkened the mood, and deviated from the source- novel, by showing the complexity of the mother-son relationship, which is arguably the cornerstone of Indian society. Instead of being filled with pure devotion to one’s mother, Apu is indirectly, though not intentionally, responsible for her death. Over time, however, Indian audiences have come to agree with international critics, that this is another Ray masterpiece. Although not at poetic as Pather Panchali, it has an edge as it charts the progress of its hero, like a classic coming-of- age novel. -

BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY Department of Bengali Session: 2011-2012 and Onwards

BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY Department of Bengali Session: 2011-2012 and onwards In accordance with the decision of the Academic Council of the University, the Faculty of Arts is pleased to introduce Semester System from the session 2004-05 for the Post-Graduate Course. It is hoped that such a System will give a new direction and relevance to all the Post-Graduate Course. In the light of introduction of Semester, focus has been concentrated on the different aspects of literature. In view of existence of different departments teaching, Indian & Foreign language in B.H.U, emphasis has been made for teaching of comparative literature. However, the syllabus has been enriched to contain the different aspects of Bengali literature in the Deptt. of Bengali. The Two-years Postgraduate Course will be divisible within 4 Semesters with credit system. A credit consists of attending lectures, active participation in tutorials (class test), seminars (paper presentation), field works, viva-voce etc. A student will be required to complete 16 Courses within 4 Semesters (two years) with 80 Credits. There are three categories of Courses 1- CORE COURSES 2- MAJOR ELECTIVE COURSES 3- MINOR ELECTIVE COURSES Proposed Structure for Semester Courses in MA. Bengali M.A. Course in Bengali will comprise of 4 (four) Semesters. Each semester will have 4 Courses. In all, there will be 16 Courses with total 80 credits. Of these, 8 Courses will be treated as Core Courses of 5 credits each, 4 Courses as Major Elective Courses of 5 credits each and 4 Courses as Minor Elective Courses of 5 credits each. -

Film & History: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies

Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies Volume 38, Issue 2, 2008, pp. 107-109 http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/film_and_history/toc/flm.38.2.html Gaston Roberge, Satyajit Ray: Essays 1970-2005, Manohar, New Delhi (India), 2007, 280 pp., hb , ISBN: 81-7304-735-9 Reviewed by Gëzim Alpion In its scope and depth, Gaston Roberge’s new book on Satyajit Ray, is one of the most important publications to appear on this great twentieth-century film director since his 1992 death. The book includes twenty-four essays, which were written between 1970 and 2005. The timeline is important to trace the growth and maturity of Ray’s art as well as Roberge’s admiration for and appreciation of his oeuvre. The essays were originally prompted by teaching assignments and requests for articles as well as by Roberge’s long-standing and growing interest in the work and talent of the Calcutta-born filmmaker. Only Essay 8, the discussion of Jana Aranya (The Middle Man, 1975), was written for this collection to ‘complement’ the book and ‘improve’ Roberge’s ‘perception of the evolution’ (p. 14) he seeks to describe from the Apu trilogy to the Heart trilogy. Some of the essays have been edited slightly by the author to avoid repetition and, more importantly, to reflect important changes in technology since the time the articles were first published. So, for instance, in Essay 13, which appeared in print initially in 1974, Roberge rightly argues that the editing was warranted by the fact that, in the digital era, the technology of film can no longer be defined solely as the succession of still images. -

Satyajit Ray at 100: Why Sharmila Tagore Considers 'Devi' Her Best

TALKING FILMS Satyajit Ray at 100: Why Sharmila Tagore considers ‘Devi’ her best collaboration with the master The 1960 classic, an examination of the tussle between blind faith and rationality, was one of five Ray productions to feature Tagore. Sharmila Tagore Jan 27, 2021 · 03:30 pm Sharmila Tagore in Satyajit Ray’s Devi (1960) | Satyajit Ray Productions Satyajit Ray arrived on the planet nearly a hundred years ago in 1921 and in the world of cinema with Pather Panchali in 1955. Devi, released in 1960, was his sixth feature, and followed the Apu Trilogy, Parash Pathar and Jalsaghar. Apur Sansar, the concluding chapter of the trilogy, introduced Soumitra Chatterjee and Sharmila Tagore. Both actors would become an indelible part of Ray’s cinematic universe. The haunting Devi, set in nineteenth-century Bengal and at the intersection of blind faith and rationality, was Tagore’s first lead role. She plays Doyamayee, a member of an aristocratic family who is declared to be the living embodiment of the goddess Kali by her father- in-law Kalikinkar (Chhabi Biswas). The gentle and tradition-bound Doyamayee is unable to resist the cult that builds up around her. Her husband Umaprasad (Soumitra Chatterjee) is equally unable to persuade his father that his wife is all too human. Adapted by Ray from a short story by Prabhat Kumar Mukherjee and beautifully shot by Subrata Mitra and designed by Bansi Chadragupta, Devi provides an early peek into Tagore’s estimable acting abilities. Then only 14 years old, Tagore delivered what she describes in the following essay as her “favourite performance”. -

Pather Panchali Aparajito the World of Apu Trois Couleurs: Bleu

Trilogies (of sorts) January 11, 2016 Pather Panchali (1955) 1:59 Dir. Satyajit Ray in Bengali The first of the Apu Trilogy — Impoverished priest, dreaming of a better English subtitles life for himself and his family, leaves his rural Bengal village in search (b&w) of work. January 25, 2016 Aparajito (1956) 1:50 Dir. Satyajit Ray in Bengali The second of the Apu Trilogy — Following his father's death, a boy English subtitles leaves home to study in Calcutta, while his mother must face a life (b&w) alone. February 8, 2016 The World of Apu (1959) 1:58 Dir. Satyajit Ray in Bengali Third and final film of the Apu Trilogy — Follows Apu's life as an English subtitles orphaned adult aspiring to be a writer as he lives through poverty, and (b&w) the unforeseen turn of events. February 22, 2016 Trois Couleurs: Bleu (1993) 1:38 Dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski in French A woman struggles to find a way to live her life after the death of her English subtitles husband and child. (color) All Movies 7:30 pm at the Dignity/Washington Center Trilogies (of sorts) March 7, 2016 Trois Couleurs: Blanc (1994) 1:31 Dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski in French Second of a trilogy of films dealing with contemporary French society English subtitles shows a Polish immigrant who wants to get even with his former wife. (color) March 21, 2016 Trois Couleurs: Rouge (1994) 1:39 Dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski in French Final entry in a trilogy of films dealing with contemporary French English subtitles society concerns a model who discovers her neighbor is keen on (color) invading people's privacy. -

Portrayal of Environment in Cinema: a Comparative Study of 'Pather Panchali'

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 3; Issue 5; May 2017; Page No. 45-48 Portrayal of environment in cinema: A comparative study of ‘Pather panchali’ & ‘Dreams’ Ram Prakash Dwivedi Department of Hindi journalism & Mass Communication, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India Abstract Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) and Akira Kurosawa (1910-198) are the world-famous filmmakers. Coincidentally, they were contemporary and friends. They were also sources of inspiration for each other. Their films are a landmark example of creative cine-language. In most of their movies, nature and the environment are as important as the human characters. Rather, the human being is guided by the nature to act upon. Their movies incorporate nature as an essential component for human activities. Portrayal of nature, in Ray’s movies, is different from that of Kurosawa. To Ray’s films environment and nature comes as part of daily life or seasonal change, whereas Kurosawa represents nature as phenomena like rain, volcanic eruptions, tsunami and earthquakes. This difference is the result of separate geographical conditions of India and Japan. Japan is environmentally very sensitive country, whereas India, due to its larger landmass, does not feel such sensitivity. Pather Panchali (1955) is considered as a masterpiece of parallel cinema and reflects reality. The film was made with on location shooting technique. This film, therefore, depicts the nature and environment of Bengal. In Dreams (1990) imagination is more important than reality. -

Artist Recreates Satyajit Ray S Film Posters on 100Th Birth Anniversary

Artist recreates Satyajit Ray's film posters on 100th birth anniversary to depict Covid crisis An artist marked 100 years of legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray by recreating his iconic film posters to depict the Covid-19 crisis in India. Krishna Priya Pallavi Writer [email protected] If I am not writing on fashion, places you can travel to for that perfect holiday, mental health, trending topics, I am probably escaping the city for a vacation, eating a scrumptious meal at a quaint cafe, and so much more in between. Love to travel (obviously), dance, explore new places, read extensively and try out new and exciting dishes. Works as Senior Sub-Editor at India Today Digital. Aniket Mitra used posters from Satyajit Ray's iconic films to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India Photo: Facebook/Aniket Mitra Satyajit Ray had an inedible mark on the Indian cinema. His films are admired by cinephiles all over the world. May 2 marks 100 years since Satyajit Ray was born, and to celebrate his 100th birth anniversary, an artist paid the legendary filmmaker a poignant and relevant tribute. A Mumbai-based artist named Aniket Mitra celebrated the historic day by reimagining Satyajit Ray's iconic film posters amid the Covid times. ARTIST RECREATES SATYAJIT RAY'S FILM POSTERS TO DEPICT COVID CRISIS Aniket Mitra used ten films by Satyajit Ray to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India. Posters of films like Pather Panchali, Devi, Nayak, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya, Mahanagar, Ashani Sanket and more, were used to show the citizens' struggle during the second wave of the deadly virus. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

Intermedialtranslation As Circulation

Journal of World Literature 5 (2020) 568–586 brill.com/jwl Intermedial Translation as Circulation Chu Tien-wen, Taiwan New Cinema, and Taiwan Literature Jessica Siu-yin Yeung soas University of London, London, UK [email protected] Abstract We generally believe that literature first circulates nationally and then scales up through translation and reception at an international level. In contrast, I argue that Taiwan literature first attained international acclaim through intermedial translation during the New Cinema period (1982–90) and was only then subsequently recognized nationally. These intermedial translations included not only adaptations of literature for film, but also collaborations between authors who acted as screenwriters and film- makers. The films resulting from these collaborations repositioned Taiwan as a mul- tilingual, multicultural and democratic nation. These shifts in media facilitated the circulation of these new narratives. Filmmakers could circumvent censorship at home and reach international audiences at Western film festivals. The international success ensured the wide circulation of these narratives in Taiwan. Keywords Taiwan – screenplay – film – allegory – cultural policy 1 Introduction We normally think of literature as circulating beyond the context in which it is written when it obtains national renown, which subsequently leads to interna- tional recognition through translation. In this article, I argue that the contem- porary Taiwanese writer, Chu Tien-wen (b. 1956)’s short stories and screenplays first attained international acclaim through the mode of intermedial transla- tion during the New Cinema period (1982–90) before they gained recognition © jessica siu-yin yeung, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24056480-00504005 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by 4.0Downloaded license. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

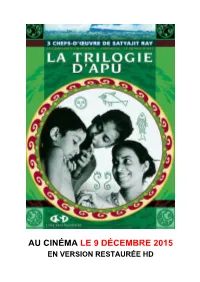

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray.