Designing Novel Biochemical Pathways to Commodity Chemicals Using

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Feedstocks in Chemicals Manufacturing

Alternative Feedstocks in Chemicals Manufacturing Joanna McFarlane and Sharon Robinson Green Chemistry and Green Engineering Conference American Chemical Society Washington DC June 27, 2006 High Feedstock Prices Negatively Impact the Chemical Industry • The high cost of natural gas has eliminated the competitive advantage for U.S. chemical production • As fuel prices rise, chemical manufacturers are shutting down domestic production and moving plants to Asia & Middle East − 50% of methanol, 45% of ammonia, and 15% of ethylene capacities have been shut down in U.S. since 2000 − U.S. import of fertilizers increased to 45% from 10% in 1990 − In 2005 8,400 jobs were lost in the chemical industry − Industry went from an 80-yr trade surplus ($20B in 1995) to trade deficits beginning in 2002 Sources: Guide to the Business of Chemistry 2005 Chemicals IOF Annual Report 2004 June 27, 2006 Energy Independence Issue: Industrial Use of Petroleum & Natural Gas 30 25 20 15 Quads/yr 10 Petroleum 5 Natural Gas Feedstock Energy Usage 0 4% of Total U.S. Energy Consumption 3% of Total U.S. Natural Gas Consumption Petrochem Ind Other Industry Electric June 27, 2006 Residential Commercial Transportation Alternative Feedstock Options for Producing Large-Volume Chemicals • Coal – gasification and liquefaction • Biomass – thermochemical, biological processes, pyrolysis • Methane – stranded, unconventional, and hydrates • Unconventional petroleum – oil shale, tar sands, heavy oil • Novel pathways – CO2/H2O, methane, hydrogen to hydrocarbons June 27, 2006 Selected -

Diversity and Mechanisms of Bacterial Dehalogenation Reactions High Number of Halogen Substituents

O.B. Janssen, T. Bosma and G.J. Poelarends Diversity and Mechanisms of 8acterial Dehalogenation Reactions Abstract Halogenated aliphatic compounds occur widespread as environmental pollutants. Since many of these compounds are xenobiotics and show large dif ferences in degradability which can be correlated to critical steps in catabolic pathways, they are suitable for studies on the evolution of dehalogenating pathways. We have investigated the degradation of 1,2-dichloroethane and 1,3- dichloropropene in detail. For both compounds, the initial step is hydrolytic dehalogenation. The 1,2-dichloroethane and 1,3-dichloropropene dehalogenases we re found to belong to different groups of identical enzymes detected in bac teria isolated from various sites. Genetic analysis and adaptation experiments indicated th at the 1,2-dichloroethane degradation pathway may be of recent evolutionary origin. The large-scale use of 1,3-dichloropropene in agriculture may have contributed to the distribution of genes encoding hydrolytic dehalogenases in the environment. Introduction The biodegradation of synthetic chlorinated chemicals that enter the environ ment is dependent on the capacity of microbial enzymes to recognize these xenobiotic molecules and cleave or labilize carbon-halogen bonds (Janssen et al., 1994). Microbiological studies have led to the isolation of a range of organisms that degrade halogenated aliphatic compounds and use them as a carbon source for growth, and a several dehalogenating enzymes that directly act on carbon halogen bonds have now been identified (Leisinger and Bader 1993; Janssen et al., 1994; Fetzner and Lingens, 1994). In a few cases, the carbon-halogen bond is not directly cleaved but labilized by introduction of other functional groups (Ensley, 1991). -

The Top 50 Commodity. Chemicals: Impact of Catalytic Process Limitations on Energy, Environment, and Economics

,,. , I /. I; i :<. .' ,'- \ -. I, 'I ., ,I ' ''I PNL-10684 ' UC-60 1 The Top 50 Commodity. Chemicals: Impact of Catalytic Process Limitations on Energy, Environment, and Economics Anna Lee Y. Tonkovich, Ph.D. Mark A. Gerber August 1995 Prepared for the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Industrial Technology Biological Chemical Technologies(OR), Research @CTR) under contractand DE-ACO6-76RLO 1830 Program Pacific Northwest Laboratory * Richland, WA 99352 DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Executive Summary The production processes for the top 50 U. S. commodity chemicals waste energy, generate unwanted byproducts, and require more than a stoichiometric amount of feedstocks. Pacific Northwest Laboratorya has quantified this impact on energy, environment, and economics for the catalytically produced commodity chemicals. An. excess of 0.83 quads of energy per year in combined process and feedstock energy is required. The major component, approximately 54%, results from low per-pass yields and the subsequent separation and recycle of unreacted feedstocks. Furthermore, the production processes, either directly or through downstream waste treatment steps, release more than 20 billion pounds of carbon dioxide per year to the environment. The cost of the wasted feedstock exceeds 2 billion dollars per year. Process limitations resulting ‘from unselective catalysis and unfavorable reaction thermodynamic constraints are the major contributors to this waste. Advanced process concepts that address these problems in an integrated manner are needed to improve process efficiency, which would reduce energy and raw material consumption, and the generation of unwanted byproducts. -

Toxic Industrial Chemicals

J R Army Med Corps 2002; 148: 371-381 J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-148-04-06 on 1 December 2002. Downloaded from Toxic Industrial Chemicals Introduction location to another. Depending on the The first chemical warfare agent of the available routes of movement, and quantity modern era, chlorine, was released with of chemical to be moved, transport can occur devastating effect on 22 April 1915 at Ypres, by truck or rail tank cars, over water by barge Belgium. Along a 4 mile front, German or boat, over land through above- or below- soldiers opened the valves of 1,600 large and ground pipelines and by air. 4,130 small cylinders containing 168 tons of Toxic chemicals may be produced by the chlorine.The gas formed a thick white cloud burning of materials (e.g., the burning of that crossed the first allied trenches in less Teflon produces perfluoroisobutylene) or by than a minute.The allied line broke, allowing their reaction if spilled into water (e.g. silanes the Germans to advance deep into allied produce hydrogen chloride and cyanides, territory. If the Germans had been fully hydrogen cyanide). prepared to exploit this breakthrough, the course and possibly the outcome of WWI Toxic Industrial Chemicals may have been very different. (TICs) Chlorine is a commodity industrial A Toxic Industrial Chemical (TIC) is defined chemical with hundreds of legitimate uses; it as: is not a "purpose designed" chemical warfare an industrial chemical which has a LCt50 agent. Phosgene, another commodity value of less than 100,000 mg.min/m3 in industrial chemical, accounted for 80% of any mammalian species and is produced in the chemical fatalities during WWI. -

CONCAWE Review Vol. 23, No. 1

Petrochemical feedstocks: the cornerstone of competitiveness Future outlook While the chemicals The future of much of Europe’s chemical industry depends heavily upon the availability of affordable industry will remain petrochemical feedstocks. largely reliant on In the Middle East, where petrochemical feedstocks are petrochemical-based cheap, and in China, where demand is surging, pro- feedstocks for decades ducers are substantially increasing capacity for a wide range of petrochemicals including polypropylene and to come, the scope for polyethylene. In the USA, cheap shale gas and eco- greater use of nomic recovery are driving a chemical industry invest- ment bonanza. But demand growth in the European renewables as Union is weak and output growth is modest. feedstocks cannot be The challenge for the chemical industry is two-fold. First, ignored. Europe is highly dependent upon imported feedstock. including enzymes, vitamins, organic acids, amino Oil, the most important, is globally traded, and input acids, polymers and thickeners for industries ranging prices are competitive. But because European gas from advanced materials to the pharmaceutical, food prices are generally high, we are at a competitive disad- and feed industries. Animal fats and vegetable oils are vantage for chemicals that use natural gas as a feed- used in the production of detergents and coatings, and stock, such as ammonia, hydrogen and the precursors natural extracts are turned into additives for personal of polyamides and methanol. Second, many industrial care and cosmetics products. processes for petrochemicals are energy intensive: cheap gas or electricity elsewhere leaves European More recently, consumer demand has powered the chemical producers at a competitive disadvantage. -

Escaping from the Commodity Dependence Trap Through Technology and Innovation

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT COMMODITIES & DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2021 Escaping from the Commodity Dependence Trap through Technology and Innovation Geneva, 2021 © 2021, United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licences, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications 405 East 42nd Street New York, New York 10017 United States of America Email: [email protected] Website: https://shop.un.org/ The designations employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of any firm or licensed process does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/DITC/COM/2021/1 ISBN: 978-92-1-1130188 eISBN: 978-92-1-403046-1 ISSN: 2519-8580 eISSN: 2524-2709 Sales No.: E.21.II.D.14 COMMODITIES & DEVELOPMENT Escaping from the Commodity Dependence Trap through Technology and Innovation REPORT 2021 Acknowledgements The Commodities and Development Report 2021: Escaping from the Commodity Dependence Trap through Technology and Innovation was prepared by Janvier D. Nkurunziza (team leader), Stefan Csordás and Marco Fugazza, from the Commodities Branch of the Division on International Trade and Commodities of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). -

Attachment 8

Environmental Assessment for Food Contact Notification FCN 1641 http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/EnvironmentalDecisions/default.htm ATTACHMENT 8 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT 1. Date: February 10, 2016 2. Name of Applicant/Petitioner: Solvay Chemicals, Inc. 3. Address: 3333 Richmond Avenue Houston, Texas 77098 Lewis & Harrison LLC (Agent) 122 C Street NW Suite 505 Washington DC 20001 4. Description of Proposed Action: A. Requested Action This Food Contact Notification (FCN) requests the clearance of a food-contact substance (FCS) that is an aqueous solution containing peroxyacetic acid (PAA), hydrogen peroxide, acetic acid (AA), hydroxyethylidene 1,1-diphosphonic acid (HEDP), dipicolinic acid (DPA) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH). The FCS will be used in food processing facilities as an antimicrobial agent used in: 1) process water (processing aid) and ice used in the production and preparation of poultry products such as post-main chiller (air or water) secondary processing of whole birds, carcasses, parts and pieces, skin on or off and organs, in the washing, rinsing, cooling and processing of poultry products; and pre-air chiller dip tanks and post-main water chiller systems as finishing chillers; in spray, wash, rinse, dip, chiller water, low-temperature (e.g., less than 40oF) immersion baths, or scald water for whole or cut poultry carcasses, parts, trim, and organs; and, 2) Process water, ice, or brine used for washing, rinsing, or cooling of processed and pre formed meat as defined in 21 CFR 170.3(n)(29) and poultry -

Organic Commodity Chemicals from Biomass

CHAPTER 13 Organic Commodity Chemicals from Biomass I. INTRODUCTION Biomass is utilized worldwide as a source of many naturally occurring and some synthetic specialty chemicals and cellulosic and starchy polymers. High- value, low-volume products, including many flavorings, drugs, fragrances, dyes, oils, waxes, tannins, resins, gums, rubbers, pesticides, and specialty polymers, are commercially extracted from or produced by conversion of biomass feedstocks. However, biomass conversion to commodity chemicals, which includes the vast majority of commercial organic chemicals, polymers, and plastics, is used to only a limited extent. This was not the case up to the early 1900s. Chars, methanol, acetic acid, acetone, and several pyroligneous chemicals were manufactured by pyrolysis of hardwoods (Chapter 8). The naval stores industry relied upon softwoods as sources of turpentines, terpenes, rosins, pitches, and tars (Chapter 10). The fermentation of sugars and starches supplied large amounts of ethanol, acetone, butanol, and other organic chemi- cals (Chapter 11). Biomass was the primary source of organic chemicals up to the mid- to late 1800s when the fossil fuel era began, and was then gradually displaced by 495 496 Organic Commodity Chemicals from Biomass fossil raw materials as the preferred feedstock for most organic commodities. Aromatic chemicals began to be manufactured in commercial quantities as a by-product of coal coking and pyrolysis processes in the late 1800s. The production of liquid hydrocarbon fuels and organic chemicals by the destruc- tive hydrogenation of coal (Bergius process) began in Germany during World War I. The petrochemical industry started in 1917 when propylene in cracked refinery streams was used to manufacture isopropyl alcohol by direct hydration. -

Bio-Based Chemicals Overview

Bio-Based Chemicals Overview 2019 PCA International Conference Vancouver, B.C., Canada, 23 - 24 September 2019 Doris de Guzman Senior Consultant – Biomaterials [email protected] OUR CORE STRENGTHS Intermediates, Fibres & Specialty Resins Soda Ash Epichlorohydrin Epoxy Resins Bisphenol A Caustic Soda EDC VCM PVC Acetone Phenol Isocyanates Chlorine Peroxy PO Polyols Polyurethanes Polyester Film Chlorohydrin PO PET Resin Bio-Materials Derivatives EO Derivatives Ethylene Oxide MEG Polyester Fibre Acetic Acid PTA Polyester Polypropylene Fibre Paraxylene Vinyl Acetate Monomer DMT Caprolactam Acrylic Fibre Acrylonitrile Adiponitrile HMDA Polyamide 6 Polyamide Fibre Adipic Acid AH Salt Polyamide 66 Polyamide Resin Polyacetal ABS & SAN PBT Polycarbonate Methanol Isodecanol DIDP Orthoxylene Styrene Methyl Acrylate Isononanol DINP Phthalic Anhydride 1,4-Butanediol Ethyl Acrylate 2-PH DPHP Acrylic Acid Unsaturated Maleic Anhydride Polyester Resin 2-Ethylhexyl Acrylate 2-EH DOP Butyl Acrylate Butanols 2 BIO-MAT E R IAL S & INT E R ME DIAT E S A monthly publication reporting market trends, pricing, and feedstock for Bio-based chemicals and their Petrochemicals counterpart Started in 2007 & Inspired by an unwavering belief that we can and will do better www.greenchemicalsblog.com 3 Value additions of Bio-based Industry to US Economy Forest Products $364bn Bio-based $22bn Chemicals $3.5bn $45bn (NA) $106bn Enzymes Textiles Agriculture $35bn and $1.11bn Forestry Biorefining Bioplastic $506m bottles and packaging Source: USDA, PCA 4 Value additions -

Purification and Characterization of a Haloalkane

APPLIED AND ENVIRONMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY, Sept. 1997, p. 3707–3710 Vol. 63, No. 9 0099-2240/97/$04.0010 Copyright © 1997, American Society for Microbiology Purification and Characterization of a Haloalkane Dehalogenase of a New Substrate Class from a g-Hexachlorocyclohexane- Degrading Bacterium, Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26 YUJI NAGATA,1* KEISUKE MIYAUCHI,1 JIRI DAMBORSKY,2 KATKA MANOVA,2 2 1 ALENA ANSORGOVA, AND MASAMICHI TAKAGI Department of Biotechnology, The University of Tokyo, Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113, Japan,1 and Laboratory of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, Masaryk University, Kotlarska 2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic2 Received 30 December 1996/Accepted 10 June 1997 The linB gene product (LinB), 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-1,4-cyclohexadiene halidohydrolase, which is involved in the degradation of g-hexachlorocyclohexane in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26 (Y. Nagata, T. Nariya, R. Ohtomo, M. Fukuda, K. Yano, and M. Takagi, J. Bacteriol. 175:6403–6410, 1993), was overproduced in E. coli and purified to homogeneity. The molecular mass of LinB was deduced to be 30 kDa by gel filtration chromatography and 32 kDa by electrophoresis on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel, indicating that LinB is a monomeric enzyme. The optimal pH for activity was 8.2. Not only monochloroalkanes (C3 to C10) but also dichloroalkanes, bromoalkanes, and chlorinated aliphatic alcohols were good substrates for LinB, sug- gesting that LinB is a haloalkane dehalogenase with a broad range of substrate specificity. These results indicate that LinB shares properties with another haloalkane dehalogenase, DhlA (S. Keuning, D. B. Janssen, and B. Witholt, J. Bacteriol. 163:635–639, 1985), which shows significant similarity to LinB in primary structure (D. -

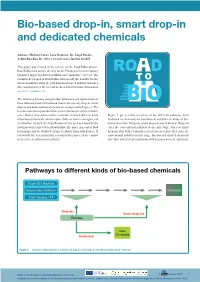

Bio-Based Drop-In, Smart Drop-In and Dedicated Chemicals

Bio-based drop-in, smart drop-in and dedicated chemicals Authors: Michael Carus, Lara Dammer, Dr. Ángel Puente, Achim Raschka, Dr. Oliver Arendt, nova-Institut GmbH This paper was created in the context of the RoadToBio-project. RoadToBio aims to pave the way for the European chemical industry towards a larger bio-based portfolio and competitive success. The roadmap developed in RoadToBio will specify the benefits for the T O chemical industry along the path from fossil-based industry towards a bioeconomy to meet the societal needs in 2030 (for more information see www.roadtobio.eu) The following briefing text provides definitions and explanations of three different kinds of bio-based chemicals, namely drop-in, smart drop-in and dedicated/novel chemicals, as depicted in Figure 1. The text does not aim to provide finite exact definitions in a strict scientific sense. Rather, it intends to outline a structure in which different kinds Figure 1 gives a first overview of the different pathways from of bio-based chemicals, which require different market strategies, can feedstock to chemicals for fossil-based and different kinds of bio- be classified. As such, the classification will be used as a basis for the based chemicals: Drop-ins, smart drop-ins and dedicated. Drop-ins roadmap work carried out in RoadToBio. The paper is meant as food enter the conventional pathway at an early stage, whereas smart for thought and we would welcome feedback from stakeholders. If drop-ins start with a biomass-related process before they enter the you would like to send us your reaction to this paper, please contact conventional pathway at a late stage. -

University of Groningen Bacterial Growth on Halogenated

University of Groningen Bacterial Growth on Halogenated Aliphatic Hydrocarbons Janssen, Dick B.; Oppentocht, Jantien E.; Poelarends, Gerrit J. Published in: EPRINTS-BOOK-TITLE IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2003 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Janssen, D. B., Oppentocht, J. E., & Poelarends, G. J. (2003). Bacterial Growth on Halogenated Aliphatic Hydrocarbons: Genetics and Biochemistry. In EPRINTS-BOOK-TITLE Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 Chapter 7 BACTERIAL GROWTH ON HALOGENATED ALIPHATIC HYDROCARBONS: GENETICS AND BIOCHEMISTRY DICK B. JANSSEN, JANTIEN E. OPPENTOCHT AND GERRIT J. POELARENDS Biochemical Laboratory, Groningen Biomolecular Sciences and Biotechnology Institute, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands 1. INTRODUCTION Many synthetically produced halogenated aliphatic compounds are xenobiotic chemicals in the sense that they do not naturally occur on earth at biologically significant concentrations.