The Continuum Hypothesis, Part I, Volume 48, Number 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set Theory, by Thomas Jech, Academic Press, New York, 1978, Xii + 621 Pp., '$53.00

BOOK REVIEWS 775 BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 3, Number 1, July 1980 © 1980 American Mathematical Society 0002-9904/80/0000-0 319/$01.75 Set theory, by Thomas Jech, Academic Press, New York, 1978, xii + 621 pp., '$53.00. "General set theory is pretty trivial stuff really" (Halmos; see [H, p. vi]). At least, with the hindsight afforded by Cantor, Zermelo, and others, it is pretty trivial to do the following. First, write down a list of axioms about sets and membership, enunciating some "obviously true" set-theoretic principles; the most popular Hst today is called ZFC (the Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms with the axiom of Choice). Next, explain how, from ZFC, one may derive all of conventional mathematics, including the general theory of transfinite cardi nals and ordinals. This "trivial" part of set theory is well covered in standard texts, such as [E] or [H]. Jech's book is an introduction to the "nontrivial" part. Now, nontrivial set theory may be roughly divided into two general areas. The first area, classical set theory, is a direct outgrowth of Cantor's work. Cantor set down the basic properties of cardinal numbers. In particular, he showed that if K is a cardinal number, then 2", or exp(/c), is a cardinal strictly larger than K (if A is a set of size K, 2* is the cardinality of the family of all subsets of A). Now starting with a cardinal K, we may form larger cardinals exp(ic), exp2(ic) = exp(exp(fc)), exp3(ic) = exp(exp2(ic)), and in fact this may be continued through the transfinite to form expa(»c) for every ordinal number a. -

GTI Diagonalization

GTI Diagonalization A. Ada, K. Sutner Carnegie Mellon University Fall 2017 1 Comments Cardinality Infinite Cardinality Diagonalization Personal Quirk 1 3 “Theoretical Computer Science (TCS)” sounds distracting–computers are just a small part of the story. I prefer Theory of Computation (ToC) and will refer to that a lot. ToC: computability theory complexity theory proof theory type theory/set theory physical realizability Personal Quirk 2 4 To my mind, the exact relationship between physics and computation is an absolutely fascinating open problem. It is obvious that the standard laws of physics support computation (ignoring resource bounds). There even are people (Landauer 1996) who claim . this amounts to an assertion that mathematics and com- puter science are a part of physics. I think that is total nonsense, but note that Landauer was no chump: in fact, he was an excellent physicists who determined the thermodynamical cost of computation and realized that reversible computation carries no cost. At any rate . Note the caveat: “ignoring resource bounds.” Just to be clear: it is not hard to set up computations that quickly overpower the whole (observable) physical universe. Even a simple recursion like this one will do. A(0, y) = y+ A(x+, 0) = A(x, 1) A(x+, y+) = A(x, A(x+, y)) This is the famous Ackermann function, and I don’t believe its study is part of physics. And there are much worse examples. But the really hard problem is going in the opposite direction: no one knows how to axiomatize physics in its entirety, so one cannot prove that all physical processes are computable. -

Set-Theoretic Geology, the Ultimate Inner Model, and New Axioms

Set-theoretic Geology, the Ultimate Inner Model, and New Axioms Justin William Henry Cavitt (860) 949-5686 [email protected] Advisor: W. Hugh Woodin Harvard University March 20, 2017 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Mathematics and Philosophy Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Author’s Note . .4 1.2 Acknowledgements . .4 2 The Independence Problem 5 2.1 Gödelian Independence and Consistency Strength . .5 2.2 Forcing and Natural Independence . .7 2.2.1 Basics of Forcing . .8 2.2.2 Forcing Facts . 11 2.2.3 The Space of All Forcing Extensions: The Generic Multiverse 15 2.3 Recap . 16 3 Approaches to New Axioms 17 3.1 Large Cardinals . 17 3.2 Inner Model Theory . 25 3.2.1 Basic Facts . 26 3.2.2 The Constructible Universe . 30 3.2.3 Other Inner Models . 35 3.2.4 Relative Constructibility . 38 3.3 Recap . 39 4 Ultimate L 40 4.1 The Axiom V = Ultimate L ..................... 41 4.2 Central Features of Ultimate L .................... 42 4.3 Further Philosophical Considerations . 47 4.4 Recap . 51 1 5 Set-theoretic Geology 52 5.1 Preliminaries . 52 5.2 The Downward Directed Grounds Hypothesis . 54 5.2.1 Bukovský’s Theorem . 54 5.2.2 The Main Argument . 61 5.3 Main Results . 65 5.4 Recap . 74 6 Conclusion 74 7 Appendix 75 7.1 Notation . 75 7.2 The ZFC Axioms . 76 7.3 The Ordinals . 77 7.4 The Universe of Sets . 77 7.5 Transitive Models and Absoluteness . -

Cardinality of Accumulation Points of Infinite Sets 1 Introduction

International Mathematical Forum, Vol. 11, 2016, no. 11, 539 - 546 HIKARI Ltd, www.m-hikari.com http://dx.doi.org/10.12988/imf.2016.6224 Cardinality of Accumulation Points of Infinite Sets A. Kalapodi CTI Diophantus, Computer Technological Institute & Press University Campus of Patras, 26504 Patras, Greece Copyright c 2016 A. Kalapodi. This article is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract One of the fundamental theorems in real analysis is the Bolzano- Weierstrass property according to which every bounded infinite set of real numbers has an accumulation point. Since this theorem essentially asserts the completeness of the real numbers, the notion of accumulation point becomes substantial. This work provides an efficient number of examples which cover every possible case in the study of accumulation points, classifying the different sizes of the derived set A0 and of the sets A \ A0, A0 n A, for an infinite set A. Mathematics Subject Classification: 97E60, 97I30 Keywords: accumulation point; derived set; countable set; uncountable set 1 Introduction The \accumulation point" is a mathematical notion due to Cantor ([2]) and although it is fundamental in real analysis, it is also important in other areas of pure mathematics, such as the study of metric or topological spaces. Following the usual notation for a metric space (X; d), we denote by V (x0;") = fx 2 X j d(x; x0) < "g the open sphere of center x0 and radius " and by D(x0;") the set V (x0;") n fx0g. -

![Arxiv:1901.02074V1 [Math.LO] 4 Jan 2019 a Xoskona Lrecrias Ih Eal Ogv Entv a Definitive a Give T to of Able Basis Be the Might Cardinals” [17]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4525/arxiv-1901-02074v1-math-lo-4-jan-2019-a-xoskona-lrecrias-ih-eal-ogv-entv-a-de-nitive-a-give-t-to-of-able-basis-be-the-might-cardinals-17-434525.webp)

Arxiv:1901.02074V1 [Math.LO] 4 Jan 2019 a Xoskona Lrecrias Ih Eal Ogv Entv a Definitive a Give T to of Able Basis Be the Might Cardinals” [17]

GENERIC LARGE CARDINALS AS AXIOMS MONROE ESKEW Abstract. We argue against Foreman’s proposal to settle the continuum hy- pothesis and other classical independent questions via the adoption of generic large cardinal axioms. Shortly after proving that the set of all real numbers has a strictly larger car- dinality than the set of integers, Cantor conjectured his Continuum Hypothesis (CH): that there is no set of a size strictly in between that of the integers and the real numbers [1]. A resolution of CH was the first problem on Hilbert’s famous list presented in 1900 [19]. G¨odel made a major advance by constructing a model of the Zermelo-Frankel (ZF) axioms for set theory in which the Axiom of Choice and CH both hold, starting from a model of ZF. This showed that the axiom system ZF, if consistent on its own, could not disprove Choice, and that ZF with Choice (ZFC), a system which suffices to formalize the methods of ordinary mathematics, could not disprove CH [16]. It remained unknown at the time whether models of ZFC could be found in which CH was false, but G¨odel began to suspect that this was possible, and hence that CH could not be settled on the basis of the normal methods of mathematics. G¨odel remained hopeful, however, that new mathemati- cal axioms known as “large cardinals” might be able to give a definitive answer on CH [17]. The independence of CH from ZFC was finally solved by Cohen’s invention of the method of forcing [2]. Cohen’s method showed that ZFC could not prove CH either, and in fact could not put any kind of bound on the possible number of cardinals between the sizes of the integers and the reals. -

Are Large Cardinal Axioms Restrictive?

Are Large Cardinal Axioms Restrictive? Neil Barton∗ 24 June 2020y Abstract The independence phenomenon in set theory, while perva- sive, can be partially addressed through the use of large cardinal axioms. A commonly assumed idea is that large cardinal axioms are species of maximality principles. In this paper, I argue that whether or not large cardinal axioms count as maximality prin- ciples depends on prior commitments concerning the richness of the subset forming operation. In particular I argue that there is a conception of maximality through absoluteness, on which large cardinal axioms are restrictive. I argue, however, that large cardi- nals are still important axioms of set theory and can play many of their usual foundational roles. Introduction Large cardinal axioms are widely viewed as some of the best candi- dates for new axioms of set theory. They are (apparently) linearly ordered by consistency strength, have substantial mathematical con- sequences for questions independent from ZFC (such as consistency statements and Projective Determinacy1), and appear natural to the ∗Fachbereich Philosophie, University of Konstanz. E-mail: neil.barton@uni- konstanz.de. yI would like to thank David Aspero,´ David Fernandez-Bret´ on,´ Monroe Eskew, Sy-David Friedman, Victoria Gitman, Luca Incurvati, Michael Potter, Chris Scam- bler, Giorgio Venturi, Matteo Viale, Kameryn Williams and audiences in Cambridge, New York, Konstanz, and Sao˜ Paulo for helpful discussion. Two anonymous ref- erees also provided helpful comments, and I am grateful for their input. I am also very grateful for the generous support of the FWF (Austrian Science Fund) through Project P 28420 (The Hyperuniverse Programme) and the VolkswagenStiftung through the project Forcing: Conceptual Change in the Foundations of Mathematics. -

17 Axiom of Choice

Math 361 Axiom of Choice 17 Axiom of Choice De¯nition 17.1. Let be a nonempty set of nonempty sets. Then a choice function for is a function f sucFh that f(S) S for all S . F 2 2 F Example 17.2. Let = (N)r . Then we can de¯ne a choice function f by F P f;g f(S) = the least element of S: Example 17.3. Let = (Z)r . Then we can de¯ne a choice function f by F P f;g f(S) = ²n where n = min z z S and, if n = 0, ² = min z= z z = n; z S . fj j j 2 g 6 f j j j j j 2 g Example 17.4. Let = (Q)r . Then we can de¯ne a choice function f as follows. F P f;g Let g : Q N be an injection. Then ! f(S) = q where g(q) = min g(r) r S . f j 2 g Example 17.5. Let = (R)r . Then it is impossible to explicitly de¯ne a choice function for . F P f;g F Axiom 17.6 (Axiom of Choice (AC)). For every set of nonempty sets, there exists a function f such that f(S) S for all S . F 2 2 F We say that f is a choice function for . F Theorem 17.7 (AC). If A; B are non-empty sets, then the following are equivalent: (a) A B ¹ (b) There exists a surjection g : B A. ! Proof. (a) (b) Suppose that A B. -

Georg Cantor English Version

GEORG CANTOR (March 3, 1845 – January 6, 1918) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK, Germany There is hardly another mathematician whose reputation among his contemporary colleagues reflected such a wide disparity of opinion: for some, GEORG FERDINAND LUDWIG PHILIPP CANTOR was a corruptor of youth (KRONECKER), while for others, he was an exceptionally gifted mathematical researcher (DAVID HILBERT 1925: Let no one be allowed to drive us from the paradise that CANTOR created for us.) GEORG CANTOR’s father was a successful merchant and stockbroker in St. Petersburg, where he lived with his family, which included six children, in the large German colony until he was forced by ill health to move to the milder climate of Germany. In Russia, GEORG was instructed by private tutors. He then attended secondary schools in Wiesbaden and Darmstadt. After he had completed his schooling with excellent grades, particularly in mathematics, his father acceded to his son’s request to pursue mathematical studies in Zurich. GEORG CANTOR could equally well have chosen a career as a violinist, in which case he would have continued the tradition of his two grandmothers, both of whom were active as respected professional musicians in St. Petersburg. When in 1863 his father died, CANTOR transferred to Berlin, where he attended lectures by KARL WEIERSTRASS, ERNST EDUARD KUMMER, and LEOPOLD KRONECKER. On completing his doctorate in 1867 with a dissertation on a topic in number theory, CANTOR did not obtain a permanent academic position. He taught for a while at a girls’ school and at an institution for training teachers, all the while working on his habilitation thesis, which led to a teaching position at the university in Halle. -

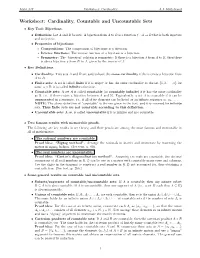

Worksheet: Cardinality, Countable and Uncountable Sets

Math 347 Worksheet: Cardinality A.J. Hildebrand Worksheet: Cardinality, Countable and Uncountable Sets • Key Tool: Bijections. • Definition: Let A and B be sets. A bijection from A to B is a function f : A ! B that is both injective and surjective. • Properties of bijections: ∗ Compositions: The composition of bijections is a bijection. ∗ Inverse functions: The inverse function of a bijection is a bijection. ∗ Symmetry: The \bijection" relation is symmetric: If there is a bijection f from A to B, then there is also a bijection g from B to A, given by the inverse of f. • Key Definitions. • Cardinality: Two sets A and B are said to have the same cardinality if there exists a bijection from A to B. • Finite sets: A set is called finite if it is empty or has the same cardinality as the set f1; 2; : : : ; ng for some n 2 N; it is called infinite otherwise. • Countable sets: A set A is called countable (or countably infinite) if it has the same cardinality as N, i.e., if there exists a bijection between A and N. Equivalently, a set A is countable if it can be enumerated in a sequence, i.e., if all of its elements can be listed as an infinite sequence a1; a2;::: . NOTE: The above definition of \countable" is the one given in the text, and it is reserved for infinite sets. Thus finite sets are not countable according to this definition. • Uncountable sets: A set is called uncountable if it is infinite and not countable. • Two famous results with memorable proofs. -

The Continuum Hypothesis

Mathematics As A Liberal Art Math 105 Fall 2015 Fowler 302 MWF 10:40am- 11:35am BY: 2015 Ron Buckmire http://sites.oxy.edu/ron/math/105/15/ Class 22: Monday October 26 Aleph One (@1) and All That The Continuum Hypothesis: Introducing @1 (Aleph One) We can show that the power set of the natural numbers has a cardinality greater than the the cardinality of the natural numbers. This result was proven in an 1891 paper by German mathematician Georg Cantor (1845-1918) who used something called a diagonalization argument in his proof. Using our formula for the cardinality of the power set, @0 jP(N)j = 2 = @1 The cardinality of the power set of the natural numbers is called @1. THEOREM Cantor's Power Set Theorem For any set S (finite or infinite), cardinality of the power set of S, i.e. P (S) is always strictly greater than the cardinality of S. Mathematically, this says that jP (S)j > jS THEOREM c > @0 The cardinality of the real numbers is greater than the cardinality of the natural numbers. DEFINITION: Uncountable An infinite set is said to be uncountable (or nondenumerable) if it has a cardinality that is greater than @0, i.e. it has more elements than the set of natural numbers. PROOF Let's use Cantor's diagonal process to show that the set of real numbers between 0 and 1 is uncountable. Math As A Liberal Art Class 22 Math 105 Spring 2015 THEOREM The Continuum Hypothesis, i.e. @1 =c The continuum hypothesis is that the cardinality of the continuum (i.e. -

The Continuum Hypothesis and Its Relation to the Lusin Set

THE CONTINUUM HYPOTHESIS AND ITS RELATION TO THE LUSIN SET CLIVE CHANG Abstract. In this paper, we prove that the Continuum Hypothesis is equiv- alent to the existence of a subset of R called a Lusin set and the property that every subset of R with cardinality < c is of first category. Additionally, we note an interesting consequence of the measure of a Lusin set, specifically that it has measure zero. We introduce the concepts of ordinals and cardinals, as well as discuss some basic point-set topology. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Ordinals 2 3. Cardinals and Countability 2 4. The Continuum Hypothesis and Aleph Numbers 2 5. The Topology on R 3 6. Meagre (First Category) and Fσ Sets 3 7. The existence of a Lusin set, assuming CH 4 8. The Lebesque Measure on R 4 9. Additional Property of the Lusin set 4 10. Lemma: CH is equivalent to R being representable as an increasing chain of countable sets 5 11. The Converse: Proof of CH from the existence of a Lusin set and a property of R 6 12. Closing Comments 6 Acknowledgments 6 References 6 1. Introduction Throughout much of the early and middle twentieth century, the Continuum Hypothesis (CH) served as one of the premier problems in the foundations of math- ematical set theory, attracting the attention of countless famous mathematicians, most notably, G¨odel,Cantor, Cohen, and Hilbert. The conjecture first advanced by Cantor in 1877, makes a claim about the relationship between the cardinality of the continuum (R) and the cardinality of the natural numbers (N), in relation to infinite set hierarchy. -

Aaboe, Asger Episodes from the Early History of Mathematics QA22 .A13 Abbott, Edwin Abbott Flatland: a Romance of Many Dimensions QA699 .A13 1953 Abbott, J

James J. Gehrig Memorial Library _________Table of Contents_______________________________________________ Section I. Cover Page..............................................i Table of Contents......................................ii Biography of James Gehrig.............................iii Section II. - Library Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘A’...................1 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘B’...................3 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘C’...................7 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘D’..................10 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘E’..................13 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘F’..................14 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘G’..................16 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘H’..................18 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘I’..................22 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘J’..................23 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘K’..................24 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘L’..................27 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘M’..................29 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘N’..................33 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘O’..................34 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘P’..................35 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘Q’..................38 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘R’..................39 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘S’..................41 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘T’..................45 Author’s Last Name beginning with ‘U’..................47 Author’s Last Name beginning