Further Examination of Potential Discrimination Among MLB Umpires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NBO Baseball Club Vol. 1 V. 2

Spring/Summer 2015 Welcome to NBO Baseball Club! Our Story or What Became of CHNBO! Our story is a simple one … players from generations. they provide an unparalleled level of many different high schools in the area use leadership, knowledge and camaraderie As with the our program to hone their skills in a com- name CHNBO, our original colors were teal and black, petitive yet educational environment. the top colors of the ‘90’s!! NBO still uses these uni- forms still today!! Current colors are Navy, Scarlet, NBO Baseball Club was created in 1995 to Royal, Black and White. Swag is in both royal and allow players from Citrus Heights, Rose- navy. ville, and Orangevale more opportunities to play extra summer games. We have played Since then my son who was on the original team, is in places such as Reno, Lake Tahoe, Carson running his own City and Redding. Having a great time and MSBL team and playing very good baseball. Ok, ok,… before many of the origi- I move forward, what does “CHNBO” mean? nal players are on Well, remember this team was originally that team and we made up of 13-14 year olds and the biggest kept the name but thing in the a young teens life at that time have begun to in- was —- wrestling, yup I said wrestling — so corporate playing when I asked about a team name a few card themes! His bounced around … here is what was agreed team name is NBO upon! First the “CH” represented our base Aces, our college area of players … Citrus Heights, ezpeez! team is the NBO Now for the “NBO”—New Baseball Order DiamondKings as in New World Wrestling Order! That’s it (Kings), our high and our name has been around forever so school team is we are keeping that going. -

Alltime Baseball Champions

ALLTIME BASEBALL CHAMPIONS MAJOR DIVISION Year Champion Head Coach Score Runnerup Site 1914 Orange William Fishback 8 4 Long Beach Poly Occidental College 1915 Hollywood Charles Webster 5 4 Norwalk Harvard Military Academy 1916 Pomona Clint Evans 87 Whittier Pomona HS 1917 San Diego Clarence Price 122 Norwalk Manual Arts HS 1918 San Diego Clarence Price 102 Huntington Park Manual Arts HS 1919 Fullerton L.O. Culp 119 Pasadena Tournament Park, Pasadena 1920 San Diego Ario Schaffer 52 Glendale San Diego HS 1921 San Diego John Perry 145 Los Angeles Lincoln Alhambra HS 1922 Franklin Francis L. Daugherty 10 Pomona Occidental College 1923 San Diego John Perry 121 Covina Fullerton HS 1924 Riverside Ashel Cunningham 63 El Monte Riverside HS 1925 San Bernardino M.P. Renfro 32 Fullerton Fullerton HS 1926 Fullerton 138 Santa Barbara Santa Barbara 1927 Fullerton Stewart Smith 9 0 Alhambra Fullerton HS 1928 San Diego Mike Morrow 30 El Monte El Monte HS 1929 San Diego Mike Morrow 41 Fullerton San Diego HS 1930 San Diego Mike Morrow 80 Cathedral San Diego HS 1931 Colton Norman Frawley 43 Citrus Colton HS 1932 San Diego Mikerow 147 Colton San Diego HS 1933 Santa Maria Kit Carlson 91 San Diego Hoover San Diego HS 1934 Cathedral Myles Regan 63 San Diego Hoover Wrigley Field, Los Angeles 1935 San Diego Mike Morrow 82 Santa Maria San Diego HS 1936 Long Beach Poly Lyle Kinnear 144 Escondido Burcham Field, Long Beach 1937 San Diego Mike Morrow 168 Excelsior San Diego HS 1938 Glendale George Sperry 6 0 Compton Wrigley Field, Los Angeles 1939 San Diego Mike Morrow 30 Long Beach Wilson San Diego HS 1940 Long Beach Wilson Fred Johnson Default (San Diego withdrew) 1941 Santa Barbara Skip W. -

Peter Gammons: the Cleveland Indians, Best Run Team in Professional Sports March 5, 2018 by Peter Gammons 7 Comments PHOENIX—T

Peter Gammons: The Cleveland Indians, best run team in professional sports March 5, 2018 by Peter Gammons 7 Comments PHOENIX—The Cleveland Indians have won 454 games the last five years, 22 more than the runner-up Boston Red Sox. In those years, the Indians spent $414M less in payroll than Boston, which at the start speaks volumes about how well the Indians have been run. Two years ago, they got to the tenth inning of an incredible World Series game 7, in a rain delay. Last October they lost an agonizing 5th game of the ALDS to the Yankees, with Corey Kluber, the best pitcher in the American League hurt. They had a 22 game winning streak that ran until September 15, their +254 run differential was 56 runs better than the next best American League team (Houston), they won 102 games, they led the league in earned run average, their starters were 81-38 and they had four players hit between 29 and 38 homers, including 29 apiece from the left side of their infield, Francisco Lindor and Jose Ramirez. And they even drew 2.05M (22nd in MLB) to the ballpark formerly known as The Jake, the only time in this five year run they drew more than 1.6M or were higher than 28th in the majors. That is the reality they live with. One could argue that in terms of talent and human player development, the growth of young front office talent (6 current general managers and three club presidents), they are presently the best run organization in the sport, especially given their financial restraints. -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

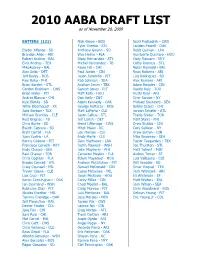

2010 AABA DRAFT LIST As of November 20, 2009

2010 AABA DRAFT LIST as of November 20, 2009 BATTERS (131) Nick Green - BOS Scott Podsednik - CWS Tyler Greene - STL Landon Powell - OAK Eliezer Alfonzo - SD Anthony Gwynn - SD Robb Quinlan - LAA Brandon Allen - ARI Wes Helms - FLA Humberto Quintero - HOU Robert Andino - BAL Diory Hernandez - ATL Cody Ransom - NYY Elvis Andrus - TEX Michel Hernandez - TB Colby Rasmus - STL MikeAubrey - BAL Koyie Hill - CHI Nolan Reimold - BAL Alex Avila - DET Paul Janish - CIN Ryan Roberts - ARI Jeff Bailey - BOS Jason Jaramillo - PIT Luis Rodriguez - SD Paul Bako - PHI Rob Johnson - SEA Alex Romero - ARI Brian Barden - STL Andruw Jones - TEX Adam Rosales - CIN Gordon Beckham - CWS Garrett Jones - PIT Randy Ruiz - TOR Brian Bixler - PIT Matt Kata - HOU Rusty Ryal - ARI Andres Blanco - CHI Don Kelly - DET Omir Santos - NY Kyle Blanks - SD Adam Kennedy - OAK Michael Saunders - SEA Willie Bloomquist - KC George Kottaras - BOS Bobby Scales - CHI Julio Borbon - TEX Matt LaPorta - CLE Jordan Schafer - ATL Michael Brantley - CLE Jason LaRue - STL Travis Snider - TOR Reid Brignac - TB Jeff Larish - DET Matt Stairs - PHI Chris Burke - SD Brent Lillibridge - CWS Drew Stubbs - CIN Everth Cabrera - SD Mitch Maier - KC Cory Sullivan - NY Brett Carroll - FLA Lou Marson - CLE Drew Sutton - CIN Juan Castro - LA Andy Marte - CLE Mike Sweeney - SEA Ronny Cedeno - PIT Gary Matthews - LAA Taylor Teagarden - TEX Francisco Cervelli - NYY Justin Maxwell - WSH Joe Thurston - STL Endy Chavez - SEA John Mayberry - PHI Matt Tolbert - MIN Raul Chavez - TOR Cameron Maybin - FLA Andres -

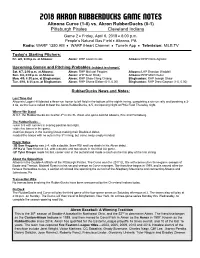

2018 Rubberducks Game Notes

2018 Akron RubberDucks Game Notes Altoona Curve (1-0) vs. Akron RubberDucks (0-1) Pittsburgh Pirates Cleveland Indians Game 2 • Friday, April 6, 2018 • 6:00 p.m. People’s Natural Gas Field • Altoona, PA Radio: WARF 1350 AM • WARF iHeart Channel • TuneIn App • Television: MiLB.TV Today’s Starting Pitchers: Fri. 4/6, 6:00 p.m. at Altoona: Akron: RHP Aaron Civale Altoona: RHP Dario Agrazal Upcoming Games and Pitching Probables (subject to change): Sat. 4/7, 2:00 p.m. at Altoona: Akron: RHP Michael Peoples Altoona: LHP Brandon Waddell Sun. 4/8, 2:00 p.m. at Altoona: Akron: LHP Sean Brady Altoona: RHP Mitch Keller Mon. 4/9, 6:35 p.m. at Binghamton: Akron: RHP Shao-Ching Chiang Binghamton: RHP Joseph Shaw Tue. 4/10, 6:35 p.m. at Binghamton: Akron: RHP Shane Bieber (0-0, 0.00) Binghamton: RHP Drew Gagnon (1-0, 0.00) RubberDucks News and Notes: Last Time Out Altoona’s Logan Hill blasted a three-run homer to left field in the bottom of the eighth inning, completing a six-run rally and breaking a 3- 3 tie, as the Curve rallied to beat the Akron RubberDucks, 6-5, on Opening Night at PNG Field Thursday night. Where We Stand At 0-1, the RubberDucks are tied for 4th in the EL West, one game behind Altoona, Erie and Harrisburg. The RubberDucks… -were 3-9 with runners in scoring position last night. -stole five bases in the game. -had five players in the starting lineup making their Double-A debut. -

Tonight's Game Information

Thursday, April 1, 2021 Game #1 (0-0) T-Mobile Park SEATTLE MARINERS (0-0) vs. SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (0-0) Home #1 (0-0) TONIGHT’S GAME INFORMATION Starting Pitchers: LHP Marco Gonzales (7-2, 3.10 in ‘20) vs. RHP Kevin Gausman (3-3, 3.62 in ‘20) 7:10 pm PT • Radio: 710 ESPN / Mariners.com • TV: ROOT SPORTS NW Day Date Opp. Time (PT) Mariners Pitcher Opposing Pitcher RADIO Friday April 2 vs. SF 7:10 pm LH Yusei Kikuchi (6-9, 5.12 in ‘20) vs. RH Johnny Cueto (2-3, 5.40 in ‘20) 710 ESPN Saturday April 3 vs. SF 6:10 pm RH Chris Flexen (8-4, 3.01 in ‘20 KBO) vs. RH Logan Webb (3-4, 5.47 in ‘20) 710 ESPN Sunday April 4 OFF DAY TONIGHT’S TILT…the Mariners open their 45th season against the San Francisco Giants at T-Mobile INSIDE THE NUMBERS Park…tonight is the first of a 3-game series vs. the Giants…following Saturday’s game, the Mariners will enjoy an off day before hosting the White Sox for a 3-game set beginning on Monday, April 5…tonight’s game will be televised live on ROOT SPORTS NW and broadcast live on 710 ESPN Seattle and the 2 Mariners Radio Network. With a win in tonight’s game, Marco Gonzales would join Randy Johnson ODDS AND ENDS…the Mariners open the season against San Francisco for the first time in club history with 2 wins on Opening Day, trailing ...also marks the first time in club history the Mariners open with an interleague opponent...the Mariners are only Félix Hernández (7) for the most 12-4 over their last 16 Opening Day contests...are 3-1 at home during that span. -

2010 Topps Baseball Set Checklist

2010 TOPPS BASEBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Prince Fielder 2 Buster Posey RC 3 Derrek Lee 4 Hanley Ramirez / Pablo Sandoval / Albert Pujols LL 5 Texas Rangers TC 6 Chicago White Sox FH 7 Mickey Mantle 8 Joe Mauer / Ichiro / Derek Jeter LL 9 Tim Lincecum NL CY 10 Clayton Kershaw 11 Orlando Cabrera 12 Doug Davis 13 Melvin Mora 14 Ted Lilly 15 Bobby Abreu 16 Johnny Cueto 17 Dexter Fowler 18 Tim Stauffer 19 Felipe Lopez 20 Tommy Hanson 21 Cristian Guzman 22 Anthony Swarzak 23 Shane Victorino 24 John Maine 25 Adam Jones 26 Zach Duke 27 Lance Berkman / Mike Hampton CC 28 Jonathan Sanchez 29 Aubrey Huff 30 Victor Martinez 31 Jason Grilli 32 Cincinnati Reds TC 33 Adam Moore RC 34 Michael Dunn RC 35 Rick Porcello 36 Tobi Stoner RC 37 Garret Anderson 38 Houston Astros TC 39 Jeff Baker 40 Josh Johnson 41 Los Angeles Dodgers FH 42 Prince Fielder / Ryan Howard / Albert Pujols LL Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Marco Scutaro 44 Howie Kendrick 45 David Hernandez 46 Chad Tracy 47 Brad Penny 48 Joey Votto 49 Jorge De La Rosa 50 Zack Greinke 51 Eric Young Jr 52 Billy Butler 53 Craig Counsell 54 John Lackey 55 Manny Ramirez 56 Andy Pettitte 57 CC Sabathia 58 Kyle Blanks 59 Kevin Gregg 60 David Wright 61 Skip Schumaker 62 Kevin Millwood 63 Josh Bard 64 Drew Stubbs RC 65 Nick Swisher 66 Kyle Phillips RC 67 Matt LaPorta 68 Brandon Inge 69 Kansas City Royals TC 70 Cole Hamels 71 Mike Hampton 72 Milwaukee Brewers FH 73 Adam Wainwright / Chris Carpenter / Jorge De La Ro LL 74 Casey Blake 75 Adrian Gonzalez 76 Joe Saunders 77 Kenshin Kawakami 78 Cesar Izturis 79 Francisco Cordero 80 Tim Lincecum 81 Ryan Theroit 82 Jason Marquis 83 Mark Teahen 84 Nate Robertson 85 Ken Griffey, Jr. -

Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., Et Al. Case

Case 15-10952-KJC Doc 712 Filed 08/05/15 Page 1 of 2014 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., et al.1 Case No. 15-10952-CSS Debtor. AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } SCOTT M. EWING, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Rust Consulting/Omni Bankruptcy, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On July 30, 2015, I caused to be served the: a) Notice of (I) Deadline for Casting Votes to Accept or Reject the Debtors’ Plan of Liquidation, (II) The Hearing to Consider Confirmation of the Combined Plan and Disclosure Statement and (III) Certain Related Matters, (the “Confirmation Hearing Notice”), b) Debtors’ Second Amended and Modified Combined Disclosure Statement and Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Combined Disclosure Statement/Plan”), c) Class 1 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 1 Ballot”), d) Class 4 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 4 Ballot”), e) Class 5 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 5 Ballot”), f) Class 4 Letter from Brown Rudnick LLP, (the “Class 4 Letter”), ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Corinthian Colleges, Inc. -

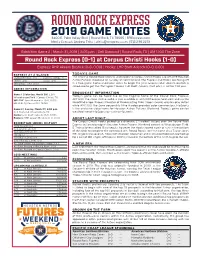

Round Rock Express 2019 GAME NOTES 3400 E

round rock Express 2019 GAME NOTES 3400 E. Palm Valley Blvd. | Round Rock, TX 78665 | RRExpress.com Media Contact: Andrew Felts | [email protected] | 512.238.2213 Exhibition Game 2 | March 31, 2019 | 2:05 p.m. | Dell Diamond | Round Rock, TX | AM 1300 The Zone Round Rock Express (0-1) at Corpus Christi Hooks (1-0) Express: RHP Akeem Bostick (0-0, 0.00) | Hooks: LHP Brett Adcock (0-0, 0.00) EXPRESS AT A GLANCE TODAY’S GAME Overall Record: 0-0 Current Streak: -- The Triple-A Round Rock Express and Double-A Corpus Christi Hooks cap off 2019 Houston Home: 0-0 Away: 0-0 Astros Futures Weekend on Sunday at Dell Diamond. The Express and Hooks are facing off Standings: T-1st (0.0) in a two-game, home-and-home series to begin the year. Express RHP Akeem Bostick is scheduled to get the start against Hooks LHP Brett Adcock. First pitch is set for 2:05 p.m. SERIES INFORMATION BROADCAST INFORMATION Game 1 | Saturday, March 30 | L 2-1 Today’s game can be heard live on the flagship home of the Round Rock Express, Whataburger Field | Corpus Christi, TX AM 1300 The Zone. Online audio is also available at am1300thezone.iheart.com and via the WP: RHP Jose Hernandez (0-0, 0.00) LP: RHP Cy Sneed (0-1, 18.00) iHeartRadio app. Express Director of Broadcasting Mike Capps handles play-by-play duties while AM 1300 The Zone personality Mike Hardge provides color commentary. FloSports Game 2 | Sunday, March 31 | 2:05 p.m. -

NATIONAL COLLEGIATE BASEBALL WRITERS NEWSLETTER (Volume 42, No

NATIONAL COLLEGIATE BASEBALL WRITERS NEWSLETTER (Volume 42, No. 4, May 2, 2003) NCBWA President’s Message By NCBWA President Rob Carolla Greetings from the President’s Desk as we present the latest edition of the NCBWA newsletter. We’re once again in the heart of the baseball season, as teams begin to jockey for positions in their conference championships. We’ve had some exciting games in my league this season, and I’m sure the same can be said around the country. One of the first items in this edition is information about voting for the NCBWA All-America Teams. On that topic, please remember to “Get Out The Vote” and submit your selections to Bo Carter for each round during the voting process. No other organization in American does as thorough a job on selecting its postseason honors and I think that is a tribute to the NCBWA and all of its members. A special thanks to Bo for all his hard work! In the last newsletter, I suggested a regular feature clarifying unusual or noteworthy scoring issues that surface during a college baseball game. Included this time is “A Scoring Philosophy”, submitted by the distinguished official scorer of the College World Series in Omaha, Louis J. Spry (see page 8 of this newsletter). Lou has been handling the official duties at the CWS for many years, and his philosophy is a very sound one that should be reviewed by every official scorer. For those of you involved in scoring (or even if you’re not!) please take a moment to look it over – it’s a great guideline.