Title: 7Th Asia Pacific Conference on the Built

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coin Cart Schedule (From 2014 to 2020) Service Hours: 10 A.M

Coin Cart Schedule (From 2014 to 2020) Service hours: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. (* denotes LCSD mobile library service locations) Date Coin Cart No. 1 Coin Cart No. 2 2014 6 Oct (Mon) to Kwun Tong District Kwun Tong District 12 Oct (Sun) Upper Ngau Tau Kok Estate Piazza Upper Ngau Tau Kok Estate Piazza 13 Oct (Mon) to Yuen Long District Tuen Mun District 19 Oct (Sun) Ching Yuet House, Tin Ching Estate, Tin Yin Tai House, Fu Tai Estate Shui Wai * 20 Oct (Mon) to North District Tai Po District 26 Oct (Sun) Wah Min House, Wah Sum Estate, Kwong Yau House, Kwong Fuk Estate * Fanling * (Service suspended on Tuesday 21 October) 27 Oct (Mon) to Wong Tai Sin District Sham Shui Po District 2 Nov (Sun) Ngan Fung House, Fung Tak Estate, Fu Wong House, Fu Cheong Estate * Diamond Hill * (Service suspended on Friday 31 October) (Service suspended on Saturday 1 November) 3 Nov (Mon) to Eastern District Wan Chai District 9 Nov (Sun) Oi Yuk House, Oi Tung Estate, Shau Kei Lay-by outside Causeway Centre, Harbour Wan * Drive (Service suspended on Thursday 6 (opposite to Sun Hung Kai Centre) November) 10 Nov (Mon) to Kwai Tsing District Islands District 16 Nov (Sun) Ching Wai House, Cheung Ching Estate, Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate, Tung Tsing Yi * Chung * (Service suspended on Monday 10 November and Wednesday 12 November) 17 Nov (Mon) to Kwun Tong District Sai Kung District 23 Nov (Sun) Tsui Ying House, Tak Chak House, Tsui Ping (South) Estate * Hau Tak Estate, Tseung Kwan O * (Service suspended on Tuesday 18 November) 24 Nov (Mon) to Sha Tin District Tsuen Wan -

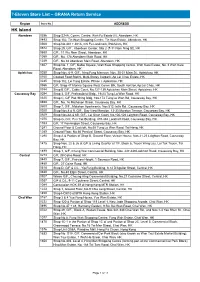

7-Eleven Store List – GRANA Return Service HK Island

7-Eleven Store List – GRANA Return Service Region Store No. ADDRESS HK Island Aberdeen 0286 Shop S24A, Comm. Centre, Wah Fu Estate (II), Aberdeen, HK 0493 Shop 102, Tin Wan Shopping Centre, Tin Wan Estate, Aberdeen, HK 0568 Shop No.401 + 401A, Chi Fu Landmark, Pokfulam, HK 0572 Shop 25, G/F., Aberdeen Center, Site 2 (7-11 Nam Ning St), HK 0688 G/F., 11 Wu Nam Street, Aberdeen, HK 1089 G/F., No. 178 Aberdeen Main Road, HK 1239 G/F., No.38 Aberdeen Main Road, Aberdeen, HK 1607 Shop No. 1, G/F, Noble Square, Wah Kwai Shopping Centre, Wah Kwai Estate, No. 3 Wah Kwai Road, Aberdeen, HK Apleichau 0030 Shop Nos. 6-9, G/F., Ning Fung Mansion, Nos. 25-31 Main St., Apleichau, HK 0165 Cooked Food Stall 6, Multi-Storey Carpark, Ap Lei Chau Estate, HK 0235 Shop 102, Lei Tung Estate, Phase I, Apleichau, HK 0366 G/F, Shop 47 Marina Square West Comm Blk, South Horizon,Ap Lei Chau, HK 0744 Shop B G/F., Coble Court, No.127-139 Apleichau Main Street, Apleichau, HK Causeway Bay 0094 Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0325 Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0468 G/F., No. 16 Matheson Street, Causeway Bay, HK 0608 Shop 7, G/F., Malahon Apartments, Nos.513 Jaffe Rd., Causeway Bay, HK 0920 Shop Nos.8 & 9, G/F., Bay View Mansion, 13-33 Moreton Terrace, Causeway Bay, HK 0929 Shop Nos.6A & 6B, G/F., Lei Shun Court, No.106-126 Leighton Road, Causeway Bay, HK 1075 Shop G, G/F, Pun Tak Building, 478-484 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay, HK 1153 G/F, 17 Pennington Street, Causeway Bay, HK 1241 Ground Floor & Cockloft, No.68 Tung Lo Wan Road, Tai Hang, HK 1289 Ground Floor, No.60 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, HK 1295 Shop A & Portion of Shop B, Ground Floor, Vulcan House, Nos.21-23 Leighton Road, Causeway Bay, HK 1475 Shop Nos. -

Address of Estate Offices Under Hong Kong Housing Authority and Hong

香港房屋委員會轄下屋邨辦事處及香港房屋委員會客務中心地址 Address of Estate Offices under Hong Kong Housing Authority and Hong Kong Housing Authority Customer Service Centre 辦事處名稱 地址 Name of Office Address Hong Kong Housing Authority 香港房屋委員會客務中心 九龍橫頭磡南道3號 3 Wang Tau Hom South Road, Kowloon Customer Service Centre No. 24-31, G/F, Lei Moon House (High Block), 鴨脷洲邨辦事處 Ap Lei Chau Estate Office 香港鴨脷洲邨利滿樓(高座)地下24-31號 Ap Lei Chau Estate, Hong Kong 蝴蝶邨辦事處 Butterfly Estate Office 屯門蝴蝶邨蝶聚樓地下 G/F, Tip Chui House, Butterfly Estate, Tuen Mun Chai Wan Estate Property Services 柴灣邨物業服務辦事處 柴灣柴灣邨灣畔樓地下 G/F, Wan Poon House, Chai Wan Estate, Chai Wan Management Office Unit 17A-24, G/F, Wah Chak House, Chak On Estate, 澤安邨辦事處 Chak On Estate Office 深水埗澤安邨華澤樓地下17A-24號 Sham Shui Po Cheung Ching Estate Property Services Unit 20-29, G/F, Ching Wai House, Cheung Ching 長青邨物業服務辦事處 青衣長青邨青槐樓地下20-29號 Management Office Estate, Tsing Yi Cheung Hang Estate Property Services Unit 1-8, G/F, Hang Lai House, Chueng Hang Estate, 長亨邨物業服務辦事處 青衣長亨邨亨麗樓地下1-8號 Management Office Tsing Yi 長康邨辦事處 Cheung Hong Estate Office 青衣長康邨康平樓地下 G/F, Hong Ping House, Cheung Hong Estate, Tsing Yi Cheung Kwai Estate Property Services Unit 101-102, Cheung Wong House, Cheung Kwai 長貴邨物業服務辦事處 長洲長貴邨長旺樓101-102號 Management Office Estate, Cheung Chau Cheung Lung Wai Estate Property G/F, King Cheung House, Cheung Lung Wai Estate, 祥龍圍邨物業服務辦事處 上水祥龍圍邨景祥樓地下 Services Management Office Sheung Shui Cheung Sha Wan Estate Property 1/F, Cheung Tai House, Cheung Sha Wan Estate, Sham 長沙灣邨物業服務辦事處 深水埗長沙灣邨長泰樓一樓 Services Management Office Shui Po Cheung -

KMB Wins Patronage Via Its Extensive Network Providing Door to Door Service

KMB wins patronage via its extensive network providing door to door service THE KOWLOON MOTOR BUS HOLDINGS LIMITED CUSTOMER SERVICE THE "OCTOPUS" SMART CARD The entire KMB fleet has been equipped with Octopus card readers since late 2000. On average, about 69% of KMB's passengers use Octopus cards for fare payment during 2001, up from 57% in 2000. This indicates a strong vote of acceptance for this convenient payment method. The reduction in the coin volume has enabled KMB to save costs on coin collection and processing. KMB's bus-bus interchange schemes have also made use of the Octopus system to offer fare discounts to passengers on the second legs of their bus journeys. KMB was one of the founders of the consortium that started the Octopus smart card system, the world's largest and most sophisticated fare payment system of its kind. Today, we have the largest number of Octopus card readers among Hong Kong's public transport operators. Bus-bus Interchange Schemes ("BBI")> KMB led the bus industry in pioneering BBI when it introduced the schemes for the Shing Mun Tunnel in 1991. This was expanded in 1999 when KMB initiated the first Octopus BBI scheme. KMB also participated in the development of inter-modal Octopus BBI software that is used by other operators for the inter-modal Octopus BBI schemes. In 2001, KMB operated four inter-modal bus-bus and bus-rail interchange schemes with other operators, namely: INTER-MODAL NO. OF KMB BBI SCHEMES ROUTES INVOLVED OPERATORS INVOLVED Overnight Cross Harbour Route 2 KMB and NWFB East Rail Feeders 7 KMB and KCRC's East Rail Tin Shui Wai (North) 1 KMB, LWB, KCRC's Light Rail Transit and Citybus Eastern Harbour Crossing 3 KMB and Citybus In the long term, the Octopus BBI schemes will bring about a win-win situation for passengers, the community and KMB. -

Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

WWF - DDC Location Plan May-2018 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 3 4 5 6 Team A Day-Off Tsuen Wan Plaza Diamond Hill MTR Exit A2 Lau Sin Street, Tin Hau King Man Street, Sai Kung (Near Sai Kung Library) Day-Off Hang Seng Bank Head Office, Central New Jade Shopping Centre, Chai Wan New Jade Shopping Centre, Chai Wan Team B Shatin Plaza Shatin Plaza Shatin Plaza (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) Hang Seng Bank Head Office, Central New Jade Shopping Centre, Chai Wan Team C Canal Road East Bridge, Causeway Bay Hong Kong MTR Station Yuen Long MTR Station Yuen Long MTR Station (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) Hang Seng Bank Head Office, Central Team D Wu Kai Sha MTR Station Exit B Canal Road East Bridge, Causeway Bay Yuen Long MTR Station Tsuen Wan Plaza (Near Footbridge) Tsuen Wan Plaza (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) World Wide House, Central World Wide House, Central Team E Tuen Mun MTR Station Wu Kai Sha MTR Station Exit B Canal Road East Bridge, Causeway Bay Tsuen Wan Plaza (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) (Near Footbridge) World Wide House, Central Team F Causeway Bay Plaza 1 (Near Footbridge) Tuen Mun MTR Station Wu Kai Sha MTR Station Exit B Chai Wan MTR Station Chai Wan MTR Station (Near Footbridge) Team G Admiralty MTR Station Exit A Causeway Bay Plaza 1 (Near Footbridge) Tuen Mun MTR Station Chai Wan MTR Station Austin MTR Station Exit B (Near Footbridge) Austin MTR Station Exit B (Near Footbridge) Team H Tai Wai MTR Station Exit D Admiralty MTR Station Exit A Causeway Bay Plaza 1 (Near Footbridge) Austin -

New Territories

Branch ATM District Branch / ATM Address Voice Navigation ATM 1009 Kwai Chung Road, Kwai Chung, New Kwai Chung Road Branch P P Territories 7-11 Shek Yi Road, Sheung Kwai Chung, New Sheung Kwai Chung Branch P P P Territories 192-194 Hing Fong Road, Kwai Chung, New Ha Kwai Chung Branch P P P Territories Shop 102, G/F Commercial Centre No.1, Cheung Hong Estate Commercial Cheung Hong Estate, 12 Ching Hong Road, P P P P Centre Branch Tsing Yi, New Territories A18-20, G/F Kwai Chung Plaza, 7-11 Kwai Foo Kwai Chung Plaza Branch P P Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories Shop No. 114D, G/F, Cheung Fat Plaza, Cheung Fat Estate Branch P P P P Cheung Fat Estate, Tsing Yi, New Territories Shop 260-265, Metroplaza, 223 Hing Fong Metroplaza Branch P P Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories 40 Kwai Cheong Road, Kwai Chung, New Kwai Cheong Road Branch P P P P Territories Shop 115, Maritime Square, Tsing Yi Island, Maritime Square Branch P P New Territories Maritime Square Wealth Management Shop 309A-B, Level 3, Maritime Square, Tsing P P P Centre Yi, New Territories ATM No.1 at Open Space Opposite to Shop No.114, LG1, Multi-storey Commercial /Car Shek Yam Shopping Centre Park Accommodation(also known as Shek Yam Shopping Centre), Shek Yam Estate, 120 Lei Muk Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories. Shop No.202, 2/F, Cheung Hong Shopping Cheung Hong Estate Centre No.2, Cheung Hong Estate, 12 Ching P Hong Road, Tsing Yi, New Territories Shop No. -

General Post Office 2 Connaught Place, Central Postmaster 2921

Access Officer - Hongkong Post District Venue/Premise/Facility Address Post Title of Access Officer Telephone Number Email Address Fax Number General Post Office 2 Connaught Place, Central Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 G/F, Kennedy Town Community Complex, 12 Rock Kennedy Town Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Hill Street, Kennedy Town Shop P116, P1, the Peak Tower, 128 Peak Road, the Peak Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Peak Central and Western Sai Ying Pun Post Office 27 Pok Fu Lam Road Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 1/F, Hong Kong Telecom CSL Tower, 322-324 Des Sheung Wan Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Voeux Road Central Wyndham Street Post Office G/F, Hoseinee House, 69 Wyndham Street Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Gloucester Road Post Office 1/F, Revenue Tower, 5 Gloucester Road, Wan Chai Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Happy Valley Post Office G/F, 14-16 Sing Woo Road, Happy Valley Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Morrison Hill Post Office G/F, 28 Oi Kwan Road, Wan Chai Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Wan Chai Wan Chai Post Office 2/F Wu Chung House, 197-213 Queen's Road East Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Perkins Road Post Office G/F, 5 Perkins Road, Jardine's Lookout Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Shops 1015-1018, 10/F, Windsor House, 311 Causeway Bay Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Gloucester -

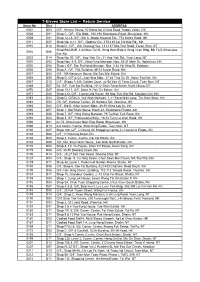

7-Eleven Store List – Return Service Store No

7-Eleven Store List – Return Service Store No. Dist ADDRESS 0001 D03 G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0008 D01 Shop C, G/F., Elle Bldg., 192-198 Shaukiwan Road, Shaukiwan, HK 0009 D01 Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0011 D07 Shop No. 6-11, G/F., Godfrey Ctr., 175-185 Lai Chi Kok Rd., Kln 0015 D12 Shop D., G/F., Win Cheung Hse, 131-137 Sha Tsui Road, Tsuen Wan, NT Shop B2A,B2B, 2-32 Man Tai St, Wing Wah Bldg & Wing Yuen Bldg, Blk F&G,Whampoa 0016 D06 Est, Kln 0022 D14 Shop No. 57, G/F., Hop Yick Ctr., 31 Hop Yick Rd., Yuen Long, NT 0030 D02 Shop Nos. 6-9, G/F., Ning Fung Mansion, Nos. 25-31 Main St., Apleichau, HK 0035 D04 Shop J G/F, San Po Kong Mansion, Nos. 2-32 Yin Hing St, Kowloon 0036 D06 Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0037 D04 G/F, 109 Geranum House, Ma Tau Wai Estate, Kln 0058 D05 Shop D, G/F & C/L, Lap Hing Bldg., 37-43 Ting On St., Ngau Tau Kok, Kln 0067 D13 G/F., Shops A & B, Golden Court, 42-58 Yan Oi Tong Circuit, Tuen Mun, NT 0069 D07 B2, G/F, Yuet Bor Building, 10-12 Shun Fong Street, Kwai Chung, NT 0070 D07 Shop 15-17, G/F, Block 9, Pak Tin Estate, Kln 0077 D08 Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0083 D04 Shop D, G/F&C/L Yuk Wah Mansion, 1-11 Fong Wah Lane, Tsz Wan Shan, Kln 0084 D03 G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 D02 G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0086 D07 Shop 1, Mei Shan House, Block 42, Shekkipmei Estate, Kln 0093 D08 Shop 7, G/F, Hing Wong Mansion, 79 Tai Kok Tsui Road, Kln 0094 D03 Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0096 D01 62-74, Shaukiwan Main East Road, Shaukiwan, HK 0098 D13 8-9 Comm. -

Sau Mau Ping (Central) – Tai Wai Station

- TRAFFIC ADVICE - Introduction of New Bus Service KMB Route No. 88 (Sau Mau Ping (Central) – Tai Wai Station) Members of the public are advised that KMB Route No. 88 will be introduced with effect from 9 July 2017 (Sunday) with service details as follows: 1. Routeing SAU MAU PING (CENTRAL) to TAI WAI STATION : via Sau Ming Road, Hiu Kwong Street, Sau Mau Ping Road, Po Lam Road, On Sau Road, On Yan Street, On Sau Road, Clear Water Bay Road, New Clear Water Bay Road, Clear Water Bay Road, Lung Cheung Road, flyover, Tate's Cairn Tunnel, Tate's Cairn Highway, Sha Lek Highway, Sha Tin Wai Road, Sha Tin Rural Committee Road, Yuen Wo Road, Tam Kon Po Street, Sha Tin Centre Street, Pak Hok Ting Street, Tai Po Road - Tai Wai, Mei Tin Road, Roundabout and Che Kung Miu Road. TAI WAI STATION to SAU MAU PING (CENTRAL) : via Mei Tin Road, Roundabout, Mei Tin Road, Tai Po Road - Tai Wai, Sha Tin Centre Street, Wang Pok Street, Yuen Wo Road, Sha Tin Rural Committee Road, Sha Tin Wai Road, Sha Lek Highway, Tate's Cairn Highway, Tate's Cairn Tunnel, slip road, Lung Cheung Road, Clear Water Bay Road, New Clear Water Bay Road, Clear Water Bay Road, On Sau Road, Po Lam Road, Sau Mau Ping Road, Hiu Kwong Street and Sau Ming Road. 2. Operating Hours Mondays to Fridays Hours Headway From Sau Mau Ping (Central) 5.30 a.m. – 12.00 midnight 6-15 mins From Tai Wai Station 5.30 a.m. -

Via on King Street, Unnamed Road, Tai Chung Kiu Road, Sha Tin Rural Committee Road and Tai Po Road

L. S. NO. 2 TO GAZETTE NO. 50/2004L.N. 203 of 2004 B1965 Air-Conditioned New Territories Route No. 284 Ravana Garden—Sha Tin Central RAVANA GARDEN to SHA TIN CENTRAL: via On King Street, unnamed road, Tai Chung Kiu Road, Sha Tin Rural Committee Road and Tai Po Road. SHA TIN CENTRAL to RAVANA GARDEN: via Sha Tin Centre Street, Wang Pok Street, Yuen Wo Road, Sha Tin Rural Committee Road, Tai Chung Kiu Road and On King Street. Air-Conditioned New Territories Route No. 285 Bayshore Towers—Heng On (Circular) BAYSHORE TOWERS to HENG ON (CIRCULAR): via On Chun Street, On Yuen Street, Sai Sha Road, Ma On Shan Road, Kam Ying Road, Sai Sha Road, Hang Hong Street, Hang Kam Street, Heng On Bus Terminus, Hang Kam Street, Hang Hong Street, Ma On Shan Road, On Chiu Street and On Chun Street. Special trips are operated from the stop on Kam Ying Road outside Kam Lung Court to Heng On. Air-Conditioned New Territories Route No. 286M Ma On Shan Town Centre—Diamond Hill MTR Station (Circular) MA ON SHAN TOWN CENTRE to DIAMOND HILL MTR STATION (CIRCULAR): via Sai Sha Road, Hang Hong Street, Chung On Estate access road, Chung On Bus Terminus, Chung On Estate access road, Sai Sha Road, roundabout, Hang Fai Street, Ning Tai Road, Po Tai Street, Ning Tai Road, Hang Tai Road, Hang Shun Street, A Kung Kok Street, Shek Mun Interchange, *(Tate’s Cairn Highway), Tate’s Cairn Tunnel, Hammer Hill Road, roundabout, Fung Tak Road, Lung Poon Street, Diamond Hill MTR Station Bus Terminus, Lung Poon Street, Tai Hom Road, Tate’s Cairn Tunnel, Tate’s Cairn Highway, Shek Mun Interchange, A Kung Kok Street, Hang Shun Street, Hang Tai Road, Ning Tai Road, Hang Fai Street, roundabout, Sai Sha Road, On Yuen Street, On Chun Street, On Chiu Street and Sai Sha Road. -

Office Address of the Labour Relations Division

If you wish to make enquiries or complaints or lodge claims on matters related to the Employment Ordinance, the Minimum Wage Ordinance or contracts of employment with the Labour Department, please approach, according to your place of work, the nearby branch office of the Labour Relations Division for assistance. Office address Areas covered Labour Relations Division (Hong Kong East) (Eastern side of Arsenal Street), HK Arts Centre, Wan Chai, Causeway Bay, 12/F, 14 Taikoo Wan Road, Taikoo Shing, Happy Valley, Tin Hau, Fortress Hill, North Point, Taikoo Place, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong. Shau Ki Wan, Chai Wan, Tai Tam, Stanley, Repulse Bay, Chung Hum Kok, South Bay, Deep Water Bay (east), Shek O and Po Toi Island. Labour Relations Division (Hong Kong West) (Western side of Arsenal Street including Police Headquarters), HK Academy 3/F, Western Magistracy Building, of Performing Arts, Fenwick Pier, Admiralty, Central District, Sheung Wan, 2A Pok Fu Lam Road, The Peak, Sai Ying Pun, Kennedy Town, Cyberport, Residence Bel-air, Hong Kong. Aberdeen, Wong Chuk Hang, Deep Water Bay (west), Peng Chau, Cheung Chau, Lamma Island, Shek Kwu Chau, Hei Ling Chau, Siu A Chau, Tai A Chau, Tung Lung Chau, Discovery Bay and Mui Wo of Lantau Island. Labour Relations Division (Kowloon East) To Kwa Wan, Ma Tau Wai, Hung Hom, Ho Man Tin, Kowloon City, UGF, Trade and Industry Tower, Kowloon Tong (eastern side of Waterloo Road), Wang Tau Hom, San Po 3 Concorde Road, Kowloon. Kong, Wong Tai Sin, Tsz Wan Shan, Diamond Hill, Choi Hung Estate, Ngau Chi Wan and Kowloon Bay (including Telford Gardens and Richland Gardens). -

APRIL Outpatient Direct Billing Panel Network (Hong Kong)

APRIL Outpatient Direct Billing Panel Network (Hong Kong) Page 3: General Practitioners Page 58: Specialists Page 90: Physiotherapy, Diagnostic Imaging & Lab Centre INTRODUCTION AND TERMS OF USE APRIL’s Outpatient Direct Billing Network is designed to provide our members with a service that makes claiming for outpatient services quick and convenient. When members with a valid APRIL Member Card use clinics within our network, APRIL will settle eligible medical expenses incurred directly with the medical provider. Only members with outpatient benefits can use direct billing services. Please note that Moratorium policies are not eligible to this service. Use of this list is governed by your Policy’s Terms and Conditions and is also subject to the guidelines, exclusions and remarks listed below. Download our Easy Claim app on your smartphone to search and locate healthcare providers within our Asia network: With the app, you can: Search a healthcare practitioner by name, location or specialty. Check whether you are eligible for direct billing in the displayed facilities To verify your eligibility for direct billing, log in to the app and click on the “E-card” button: • If the code “DB” is displayed on your card, you are eligible for direct billing within our whole Asia general network. • If the code “PNW” is displayed, you can enjoy direct billing within our Panel Network. Reminder Members with outpatient benefits should have access to this service, however, if you have not used our Outpatient Direct Billing Network before, or have any problems using the Network, please call us at +852 2526 0505 (Hong Kong) or email your questions to [email protected] Inpatient Direct Billing For inpatient treatment, APRIL can arrange direct billing if proper notification and documentation are provided and subject to the hospital’s agreement.