The Moody New Yorker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Measurement Report

THEATER SUBDISTRICT COUNCIL, LDC Performance Measurement Report I. How efficiently or effectively has TSC been in making grants which serve to enhance the long- term viability of Broadway through the production of plays and small musicals? The TSC awards grants, among other purposes, to facilitate the production of plays and musicals. The current round, awarding over $2.16 million in grants for programs, which have or are expected to result in the production of plays or musicals, have been awarded to the following organizations: • Classical Theatre of Harlem $100,000 (2009) Evaluation: A TSC grant enabled the Classical Theatre of Harlem to produce Archbishop Supreme Tartuffe at the Harold Clurman Theatre on Theatre Row in Summer 2009. This critically acclaimed reworking of Moliere’s Tartuffe directed by Alfred Preisser and featuring Andre DeShields was an audience success. The play was part of the theater’s Project Classics initiative, designed to bring theater to an underserved and under-represented segment of the community. Marketing efforts successfully targeted audiences from north of 116th Street through deep discounts and other ticket offers. • Fractured Atlas $200,000 (2010) Evaluation: Fractured Atlas used TSC support for a three-part program to improve the efficiency of rehearsal and performance space options, gather useful workspace data, and increase the availability of affordable workspace for performing arts groups in the five boroughs. Software designers created a space reservation calendar and rental engine; software for an enhanced data-reporting template was written, and strategies to increase the use of nontraditional spaces for rehearsal and performance were developed. • Lark Play Development Center $160,000 (2010) Evaluation: Lark selected four New York playwrights from diverse backgrounds to participate in a new fellowship program: Joshua Allen, Thomas Bradshaw, Bekah Brunstetter, and Andrea Thome. -

HERRICK GOLDMAN LIGHTING DESIGNER Website: HG Lighting Design Inc

IGHTING ESIGNER HERRICK GOLDMAN L D Website: HG Lighting Design inc. Phone: 917-797-3624 www.HGLightingDesign.com 1460 Broadway 16th floor E-mail: [email protected] New York, NY 10036 Honors & Awards: •2009 LDI Redden Award for Excellence in Theatrical Design •2009 Henry Hewes (formerly American Theatre Wing) Nominee for “Rooms a Rock Romance” •2009 ISES Big Apple award for Best Event Lighting •2010 Live Design Excellence award for Best Theatrical Lighting Design •2011 Henry Hewes Nominee for Joe DiPietro’s “Falling for Eve” Upcoming: Alice in Wonderland Pittsburgh Ballet, Winter ‘17 Selected Experience: •New York Theater (partial). Jason Bishop The New Victory Theater, Fall ‘16 Jasper in Deadland Ryan Scott Oliver/ Brandon Ivie dir. Prospect Theater Company Off-Broadway, NYC March ‘14 50 Shades! the Musical (Parody) Elektra Theatre Off-Broadway, NYC Jan ‘14 Two Point Oh 59 e 59 theatres Off-Broadway, NYC Oct. ‘13 Amigo Duende (Joshua Henry & Luis Salgado) Museo Del Barrio, NYC Oct. ‘12 Myths & Hymns Adam Guettel Prospect Theater co. Off-Broadway, NYC Jan. ‘12 Falling For Eve by Joe Dipietro The York Theater, Off-Broadway NYC July. ‘10 I’ll Be Damned The Vineyard Theater, Off-Broadway NYC June. ‘10 666 The Minetta Lane Theater Off-Broadway, NYC March. ‘10 Loaded Theater Row Off-Broadway, NYC Nov. ‘09 Flamingo Court New World Stages Off-Broadway, NYC June ‘09 Rooms a Rock Romance Directed by Scott Schwartz, New World Stages, NYC March. ‘09 The Who’s Tommy 15th anniversary concert August Wilson Theater, Broadway, NYC Dec. ‘08 Flamingo Court New World Stages Off-Broadway, NYC July ‘08 The Last Starfighter (The musical) Theater @ St. -

Brand-New Theaters Planned for Off-B'way

20100503-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 4/30/2010 7:40 PM Page 1 INSIDE THE BEST SMALL TOP STORIES BUSINESS A little less luxury NEWS YOU goes a long way NEVER HEARD on Madison Ave. ® Greg David Page 11 PAGE 2 Properties deemed ‘distressed’ up 19% VOL. XXVI, NO. 18 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM MAY 3-9, 2010 PRICE: $3.00 PAGE 2 ABC Brand-new News gets cut theaters to the bone planned for PAGE 3 Bankrupt St. V’s off-B’way yields rich pickings PAGE 3 Hit shows and lower prices spur revival as Surprise beneficiary one owner expands of D.C. bank attacks IN THE MARKETS, PAGE 4 BY MIRIAM KREININ SOUCCAR Soup Nazi making in the past few months, Catherine 8th Ave. comeback Russell has been receiving calls constant- ly from producers trying to rent a stage at NEW YORK, NEW YORK, P. 6 her off-Broadway theater complex. In fact, the demand is so great that Ms. Russell—whose two stages are filled with the long-running shows The BUSINESS LIVES Fantasticks and Perfect Crime—plans to build more theaters. The general man- ager of the Snapple Theater Center at West 50th Street and Broadway is in negotiations with landlords at two midtown locations to build one com- plex with two 249-seat theaters and an- other with two 249-seat theaters and a 99-seat stage. She hopes to sign the leases within the next two months and finish the theaters by October. “There are not enough theaters cen- GOTHAM GIGS by gettycontour images / SPRING AWAKENING: See NEW THEATERS on Page 22 Healing hands at the “Going to Broadway has Bronx Zoo P. -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

Exile Vol. XXXIX No. 1 Ezra Pound Denison University

Exile Volume 39 | Number 1 Article 1 1992 Exile Vol. XXXIX No. 1 Ezra Pound Denison University Kristin Kruse Denison University Chris Macaluso Denison University Charis Brummitt Denison University Kristen Padden Denison University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/exile Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Pound, Ezra; Kruse, Kristin; Macaluso, Chris; Brummitt, Charis; Padden, Kristen; Rudgers, Jen; Nix, Kevin; Croft, Rich; Widmaier, Beth; Rudder, Katy; Wanat, Matt; Kang, Ishak; Dempsey, Erin; Dunham, Trey; Bowers, Craig; Christie, Carey; Lott, Erin; Fair, Adrienne; Stind, Ellison J.; Allen, Trevett; Zobay, Andrew; Heckert, Andy; Polumbus, Christina; Wendell, Jennifer; Brady, Travis; and Gallagher, Annette (1992) "Exile Vol. XXXIX No. 1," Exile: Vol. 39 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/exile/vol39/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Exile by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Exile Vol. XXXIX No. 1 Authors Ezra Pound, Kristin Kruse, Chris Macaluso, Charis Brummitt, Kristen Padden, Jen Rudgers, Kevin Nix, Rich Croft, Beth Widmaier, Katy Rudder, Matt aW nat, Ishak Kang, Erin Dempsey, Trey Dunham, Craig Bowers, Carey Christie, Erin Lott, Adrienne Fair, Ellison J. Stind, Trevett Allen, Andrew Zobay, Andy Heckert, Christina Polumbus, Jennifer Wendell, Travis Brady, and Annette Gallagher This article is available in Exile: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/exile/vol39/iss1/1 EXILE Denison University's Literary and Art Magazine 37th Year Fall Edition Table of Contents Title Page, Ellen Gurley '93 i Epigraph, Ezra Pound ii Table of Contents iii-iv Remaining a Soldier, Kristin Kruse '93 1 You of the finer sense, Vietnam War Memorial, Brooke MacKaye 3 Broken against false knowledge, We both ride in back. -

May 15-16 + 22-23 Downtown Alliance in Association With

MAY 15-16 + 22-23 DOWNTOWN ALLIANCE IN ASSOCIATION WITH + PRESENTS DOWNTOWN LIVE MAY 15-16 + 22-23, 2021 T A BLE OF C ON T EN TS •FESTIVAL MAP •FESTIVAL SCHEDULE •NEIGHBORHOOD RECOMMENDATIONS • DEALS WORTH CHECKING OUT •ABOUT THE FESTIVAL •NOTES FROM JESSICA LAPPIN & FESTIVAL CURATORS •FESTIVAL LINEUP BY SITE • 1 BATTERY PARK PLAZA • 85 BROAD STREET • 4 NEW YORK PLAZA 1 BATTERY PARK PLAZA •ABOUT THE PARTNERS BABA ISRAEL & GRACE GALU JAMES & JEROME • KATIE MADISON • EN GARDE ARTS 85 BROAD STREET • THE TANK EISA DAVIS, KANEZA SCHAAL & JACKIE SIBBLIES DRURY DAVID GREENSPAN W/ JAMIE LAWRENCE • THE DOWNTOWN ALLIANCE ELLEN WINTER W/ MACHEL ROSS • FESTIVAL PRODUCTION TEAM 4 NEW YORK PLAZA MEGHAN FINN & KAARON BRISCOE GROUP.BR• KUHOO VERMA W/ JUSTIN RAMOS •ARTIST BIOS FESTIVAL MAP ABOUT THE FESTIVAL ive performances are back! Downtown Live brings 36 in-person performances Lto Lower Manhattan on May 15-16 and 22-23. The performances are staged at unexpected locations around the neighborhood, including a covered loading dock (4 New York Plaza), an arcade along the Stone Street Historic District (85 Broad Street) and a plaza with harbor views near The Battery (1 Battery Park Plaza). After a year of lockdowns, these in-person shows offer audience members a long-awaited chance to see LIVE theatre, contemporary performance, and music and to explore all that Lower Manhattan has to offer. (Click the stars on the map to check out the performances at each stage) MAY 15-26 S2 S3 S1 STAGE 1 STAGE 2 STAGE 3 1 BATTERY PARK PLAZA 85 BROAD STREET 4 NEW YORK PLAZA -

To See the Full #Wemakeevents Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA TOTAL PARTICIPANTS - 1,872 and counting Participation List Name City State jkl; Big Friendly Productions Birmingham Alabama Design Prodcutions Birmingham Alabama Dossman FX Birmingham Alabama JAMM Entertainment Services Birmingham Alabama MoB Productions Birmingham Alabama MV Entertainment Birmingham Alabama IATSE Local78 Birmingham Alabama Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama Alys Stephens Performing Arts Center (Alabama Symphony) Birmingham Alabama Avondale Birmingham Alabama Iron City Birmingham Alabama Lyric Theatre - Birmingham Birmingham Alabama Saturn Birmingham Alabama The Nick Birmingham Alabama Work Play Birmingham Alabama American Legion Post 199 Fairhope Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama The Camp Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Studio Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Edwards Residence Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Mainstreet at The Wharf Orange Beach Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama -

URL 100% (Korea)

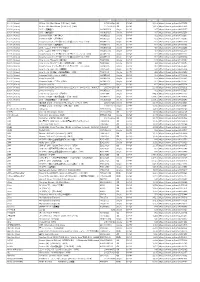

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

12-22 Masterwork Chorus Messiah

Friday Evening, January 11, 2013, at 5:30 Jodi Kaplan presents BOOKING DANCE FESTIVAL NYC AN EVENING OF DYNAMIC SHOWCASES FEATURING THE BEST OF DANCE FROM ACROSS THE U.S. See a stunning array of 27 dance companies from across the U.S. performing exquisite and diverse showcases in the most breathtaking setting imaginable. www.bookingdance.com Thank you for joining us at Jazz at Lincoln Center for this once-in-a-lifetime experience! There will be no intermission during this performance. The audience is free to come and go throughout the evening. Kindly exit as needed during speaking pauses every hour. Please turn off all cell phones, alarms, and other electronic devices. THE ALLEN ROOM JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER’S FREDERICK P. ROSE HALL jalc.org P R O G R A M Booking Dance Festival NYC Featured Artists MAIN ROSTER GUEST ARTISTS Banafsheh (NYC) ACB Company (NYC) www.namah.net www.acbdance.org Dallas Black Dance Theatre (Dallas, TX) Ashley A. Friend (NYC) www.dbdt.com www.dancecore.org Freespace Dance (NYC) BEings Dance (NYC) www.freespacedance.com www.beingsdance.com Michael Mao Dance (NYC) BODYART (NYC) www.michaelmaodance.org www.bodyartdance.com Paula Josa-Jones Performance Works (NY) Shannon Hummel/Cora Dance (NYC) www.paulajosajones.org www.coradance.com Rebecca Stenn Company (NYC) Deeply Rooted Dance Theater (Chicago, IL) www.rebeccastenncompany.com www.deeplyrootedproductions.org Marie-Christine Giordano Dance (NYC) BOUTIQUE ROSTER www.mcgiordanodance.org A Palo Seco Flamenco Company (NYC) NY2Dance (NYC) www.apalosecoflamenco.com www.ny2dance.com August Wilson Center Dance Ensemble The Francesca Harper Project (NYC) (Pittsburgh, PA) www.augustwilsoncenter.org The Nerve Tank (NYC) www.nervetank.com BodyStories: Teresa Fellion Dance (NYC) www.bodystoriesfellion.org Cori Marquis + the Nines (IX) (NYC) www.corimarquis.typepad.com Kanopy Dance Company (Madison, WI) www.kanopydance.org Tiffany Mills Company (NYC) www.tiffanymillscompany.org L.A. -

Off* for Visitors

Welcome to The best brands, the biggest selection, plus 1O% off* for visitors. Stop by Macy’s Herald Square and ask for your Macy’s Visitor Savings Pass*, good for 10% off* thousands of items throughout the store! Plus, we now ship to over 100 countries around the world, so you can enjoy international shipping online. For details, log on to macys.com/international Macy’s Herald Square Visitor Center, Lower Level (212) 494-3827 *Restrictions apply. Valid I.D. required. Details in store. NYC Official Visitor Guide A Letter from the Mayor Dear Friends: As temperatures dip, autumn turns the City’s abundant foliage to brilliant colors, providing a beautiful backdrop to the five boroughs. Neighborhoods like Fort Greene in Brooklyn, Snug Harbor on Staten Island, Long Island City in Queens and Arthur Avenue in the Bronx are rich in the cultural diversity for which the City is famous. Enjoy strolling through these communities as well as among the more than 700 acres of new parkland added in the past decade. Fall also means it is time for favorite holidays. Every October, NYC streets come alive with ghosts, goblins and revelry along Sixth Avenue during Manhattan’s Village Halloween Parade. The pomp and pageantry of Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in November make for a high-energy holiday spectacle. And in early December, Rockefeller Center’s signature tree lights up and beckons to the area’s shoppers and ice-skaters. The season also offers plenty of relaxing options for anyone seeking a break from the holiday hustle and bustle. -

Reflections Poetry Magazine 2021

REFLECTIONS 2021 The Poetry Magazine of Green Brook Middle School 1 2 REFLECTIONS 2021 The Poetry Magazine of Green Brook Middle School Faculty Advisor: Mr. Fornale Special Thanks: Ms. Subervi, Mrs. Casale, all Grade 5 and ELA Teachers, all students who submitted poetry, and all parents who encouraged them. Art Credit: Front Cover, Conrad Kohl 3 4 Grade 5 5 6 Haiku We unite to fight Darkness that is still in sight. So unite, not fight. by Samer Anshasi Minecraft Minecraft is original It is my favorite game Now Minecraft is getting its biggest update Everything In the world is being redone Crazy new features are being added Really crazy monsters are being put in Amazing blocks and biomes are coming too Fun mechanics are also being added Tools that help you build machines are being added by Zachary Anthenelli Video Games Very Interesting Digital Exciting Out of this world Galactic Addicting Monsterous Excellent Super fun games by Julian Apilado 7 Haiku: Monkeys Swinging on a vine Always wanting bananas Monkeys don’t sit still by Eva Arana Swim Team My coach is named Pat He has a twin brother named Matt. He trains us to swim fast So we don’t end up coming in last. We are the Water Wrats! by Callum Benderoth A Weird Day I don’t want to go to school today it ain’t my birthday but I’ll have fun today Or I’ll be castaway So let's go underway by Grayson P. Breen 8 Seasonal Haikus Spring Fall Spring is cold and hot Fall makes leaves fall down Spring has a lot of pollen Fall makes us were thick jackets Spring has cold long winds Fall makes us rake -

The Program Rachel Lee, Eric William Morris, Will Roland, Lance Rubin, Brent Stranathan, Jared Weiss, Jason Sweettooth Williams

Saturday, February 1, 2020 at 8:30 pm Joe Iconis The Family Nick Blaemire, Amara Brady, Liz Lark Brown, Betty Buckley, Dave Cinquegrana, Katrina Rose Dideriksen, Badia Farha, Alexandra Ferrara, Danielle Gimbal, Annie Golden, Molly Hager, Joe Iconis, Ian Kagey, Geoffrey Ko, The Program Rachel Lee, Eric William Morris, Will Roland, Lance Rubin, Brent Stranathan, Jared Weiss, Jason SweetTooth Williams This evening’s program is approximately 75 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. This performance is being livestreamed; cameras will be present. Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. Endowment support provided by Bank of America Corporate support provided by Morgan Stanley This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano The Appel Room Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall American Songbook Additional support for Lincoln Center’s American Songbook is provided by Christina and Robert Baker, EY, Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Family Foundation, The DuBose and Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund, The Shubert Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Patrons and Lincoln Center Members Public support is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center Artist catering provided by Zabar’s and Zabars.com UPCOMING AMERICAN SONGBOOK EVENTS IN THE APPEL ROOM: Wednesday, February 12 at 8:30 pm iLe Thursday, February 13 at 8:30 pm Roomful of Teeth Friday, February 14 at 8:30 pm Brandon Victor Dixon Saturday, February 15 at 8:30 pm Our Lady J Wednesday, February 26 at 8:30 pm An Evening with Natalie Merchant Thursday, February 27 at 8:30 pm Kalani Pe‘a Friday, February 28 at 8:30 pm Ali Stroker Saturday, February 29 at 8:30 pm Martin Sexton For tickets, call (212) 721-6500 or visit AmericanSongbook.org.