Choices of Business Organisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affiliate Companies in Ethiopia Analysis of Organization, Legal

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES AFFILIATE COMPANIES IN ETHIOPIA: ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATION, LEGAL FRAME WORK AND THE CURRENT PRACTICE By: Mehamed Aliye Waritu Advisor: Ato Seyoum Yohannes (LL.B, LL.M) Faculty of Law ADDIS ABABA University January, 2010 www.chilot.me Affiliate Companies in Ethiopia: Analysis of Organization, Legal Frame Work and the Current Practice A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the LLM Degree (Business Law) By Mehamed Aliye Waritu Advisor Ato Seyoum Yohannes At the Faculty of Law of the Addis Ababa University Jaunary,2010 www.chilot.me Declaration The thesis is my original work, has not been submitted for a degree in any other University and that all materials used have been duly acknowledged. Signature of confirmation Name Mehamed Aliye Waritu Signature_______________________ Date_________________________ Name of Advisor Seyoum Yohannes Signature_______________________ Date_________________________ www.chilot.me Approval Sheet by the Board of Examiners Affiliate Companies in Ethiopia: Analysis of Organization, Legal framework and the current practice Submitted, to Faculty of Law Addis Ababa University, in partial fulfilment of the requirements of LLM Degree (Business Law) By: Mehamed Aliye Waritu Approved by board of Examiners. Name Sign. 1. Advisor Seyoum Yohannes _______________ 2. Examiner __________________ _______________ 3. Examiner ___________________ _______________ www.chilot.me Acknowledgement Thanks be to Allah for helping me see the fruit of my endeavor. The thesis would not have been completed with out the support and guidance of my advisor Ato Seyoum yohannes. My special thanks goes to him. I am also indebted to my mother Shashuu Buttaa, my wife Caltu Haji and my brother Ibrahim Aliye for they have been validating, supporting and encouraging in my career development and to complete this work. -

Partnership Management & Project Portfolio Management

Partnership Management & Project Portfolio Management Partnerships and strategic management for projects, programs, quasi- projects, and operational activities In the digital age – we need appropriate socio-technical approaches, tools, and methods for: • Maintainability • Sustainability • Integration • Maturing our work activities At the conclusion of this one-hour session, participants will: • Be able to define partnership management and project portfolio management. • Be able to identify examples of governance models to support partnerships. • Be able to share examples of document/resource types for defining and managing partnerships within project portfolio management. • Be able to describe how equity relates to partnerships and partnership management. Provider, Partner, Pioneer Digital Scholarship and Research Libraries Provider, Partner, Pilgrim (those who journey, who wander and wonder) https://www.rluk.ac.uk/provider-partner-pioneer-digital-scholarship-and-the-role-of-the-research-library-symposium/ Partners and Partnership Management Partner: any individual, group or institution including governments and donors whose active participation and support are essential for the successful implementation of a project or program. Partnership Management: the process of following up on and maintaining effective, productive, and harmonious relationships with partners. It can be informal (phone, email, visits) or formal (written, signed agreements, with periodic review). What is most important is to: invest the time and resources needed to -

Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee Charter

HORIZON THERAPEUTICS PUBLIC LIMITED COMPANY CHARTER OF THE NOMINATING AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE COMMITTEE OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AMENDED EFFECTIVE: 18 FEBRUARY 2021 PURPOSE AND POLICY The primary purpose of the Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee (the “Committee”) of the Board of Directors (the “Board”) of Horizon Therapeutics Public Limited Company, an Irish public limited company (the “Company”), shall be to oversee all aspects of the Company’s corporate governance functions on behalf of the Board, including to (i) make recommendations to the Board regarding corporate governance issues; (ii) identify, review and evaluate candidates to serve as directors of the Company consistent with criteria approved by the Board and review and evaluate incumbent directors; (iii) serve as a focal point for communication between such candidates, non-committee directors and the Company’s management; (iv) nominate candidates to serve as directors; and (v) make other recommendations to the Board regarding affairs relating to the directors of the Company. The Committee shall also provide oversight assistance in connection with the Company’s legal, regulatory and ethical compliance programs, policies and procedures as established by management and the Board. The operation of the Committee and this Nominating and Corporate Governance Charter shall be subject to the constitution of the Company as in effect from time to time and the Irish Companies Act 2014, as amended by the Irish Companies (Amendment) Act 2017, the Irish Companies (Accounting) Act 2017 and as may be subsequently amended, updated or replaced from time to time (the “Companies Act”). COMPOSITION The Committee shall consist of at least two members of the Board. -

General Meetings in Ireland: Overview, Practical Law UK Practice Note Overview

General meetings in Ireland: overview, Practical Law UK Practice Note Overview... General meetings in Ireland: overview by PL Corporate Ireland, with thanks to David Brangam, Partner, Christine Quigley, Associate, and Jenny McGowran, Head of Corporate Services at Simmons & Simmons, Dublin Practice note: overview | Maintained | Ireland An overview of the key provisions of the Companies Act 2014, the Listing Rules of the Irish stock exchange trading as Euronext Dublin, the Irish Annex to the UK Corporate Governance Code and institutional investor guidance which regulate the holding of a general meeting (including an AGM). It covers how general meetings are called, the requirements for notice of a meeting and documents accompanying the notice, quorum requirements, how resolutions are proposed and passed at a general meeting and practical guidance on running an effective general meeting. Scope of this note Types of companies Traded PLC Types of general meeting Annual general meeting Extraordinary general meetings Written resolutions of members Calling a general meeting Meetings called by the board Meetings requisitioned by members Members' right to convene an EGM directly Meetings ordered by the court Auditor's ability to call meetings Liquidator's ability to call meetings Examiner's ability to call meetings Shareholders' rights in relation to general meetings Notice of meeting Notice of a meeting of a PLC Contents of notice Entitlement to receive notice How notice is given Notice periods for holding meetings © 2020 Thomson Reuters. All rights -

CHAPTER# 1 Define Joint Stock Company?

CHAPTER# 1 Define Joint Stock Company? It may be defined as an artificial person recognized by laws, with a distinctive name, a common seal, a common capital comprising transferable shares carrying limited liability and having a perpetual succession. Define Separate Legal Entity? A joint stock company is the creation of law. It has a separate legal entity of its own which is recognized by law as distinctive from persons forming it. It can sue or be sued in its name. It can own and transfer the title to property. Explain Perpetual Existence? A joint stock company has long life compared to other forms of business organizations. When company is formed and commence business, it has then a continuous life. The shareholders can come or go. It can be wound up through compliance with the provisions of companies ordinance 1984. Define Common Seal? Joint Stock company is an artificial person created by law, it therefore cannot sign documents for itself. The common seal with the name of the company engraved on it is, therefore used as a substitute for its signature. What is Company Limited by Shares? This is the principal from of company which is registered with the registrar of joint stock company under the companies ordinance 1984. Its capital is divided into number of shares. The shares can be freely transferred and sold. The liability of members is limited to the amount if any, unpaid on the shares held by them. Define Private Limited Company? It can be formed (a) at least by two persons and its total membership cannot exceed 50 (b) the company by its articles also restricts the right to transfer it shares (c) it also prohibits any invitation to the public for investment. -

TD 2019 Annual Report Principal Subsidiaries

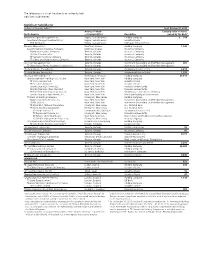

The following is a list of the directly or indirectly held significant subsidiaries. Significant Subsidiaries1 (millions of Canadian dollars) As at October 31, 2019 Address of Head Carrying value of shares North America or Principal Office2 Description owned by the Bank3 Greystone Capital Management Inc. Regina, Saskatchewan Holding Company $ 714 Greystone Managed Investments Inc. Regina, Saskatchewan Securities Dealer GMI Serving Inc. Regina, Saskatchewan Mortgage Servicing Entity Meloche Monnex Inc. Montreal, Québec Holding Company 1,595 Security National Insurance Company Montreal, Québec Insurance Company Primmum Insurance Company Toronto, Ontario Insurance Company TD Direct Insurance Inc. Toronto, Ontario Insurance Company TD General Insurance Company Toronto, Ontario Insurance Company TD Home and Auto Insurance Company Toronto, Ontario Insurance Company TD Asset Management Inc. Toronto, Ontario Investment Counselling and Portfolio Management 365 TD Waterhouse Private Investment Counsel Inc. Toronto, Ontario Investment Counselling and Portfolio Management TD Auto Finance (Canada) Inc. Toronto, Ontario Automotive Finance Entity 2,619 TD Auto Finance Services Inc. Toronto, Ontario Automotive Finance Entity 1,370 TD Group US Holdings LLC Wilmington, Delaware Holding Company 67,117 Toronto Dominion Holdings (U.S.A.), Inc. New York, New York Holding Company TD Prime Services LLC New York, New York Securities Dealer TD Securities (USA) LLC New York, New York Securities Dealer Toronto Dominion (Texas) LLC New York, New York Financial Services Entity Toronto Dominion (New York) LLC New York, New York Financial Services Entity Toronto Dominion Capital (U.S.A.), Inc. New York, New York Small Business Investment Company Toronto Dominion Investments, Inc. New York, New York Merchant Banking and Investments TD Bank US Holding Company Cherry Hill, New Jersey Holding Company Epoch Investment Partners, Inc. -

Ownership and Control of Private Firms

WJEC BUSINESS STUDIES A LEVEL 2008 Spec. Issue 2 2012 Page 1 RESOURCES. Ownership and Control of Private Firms. Introduction Sole traders are the most popular of business Business managers as a businesses steadily legal forms, owned and often run by a single in- grows in size, are in the main able to cope, dividual they are found on every street corner learn and develop new skills. Change is grad- in the country. A quick examination of a busi- ual, there are few major shocks. Unfortu- ness directory such as yellow pages, will show nately business growth is unlikely to be a that there are thousands in every town or city. steady process, with regular growth of say There are both advantages and disadvantages 5% a year. Instead business growth often oc- to operating as a sole trader, and these are: curs as rapid bursts, followed by a period of steady growth, then followed again by a rapid Advantages. burst in growth.. Easy to set up – it is just a matter of in- The change in legal form of business often forming the Inland Revenue that an individ- mirrors this growth pattern. The move from ual is self employed and registering for sole trader to partnership involves injections class 2 national insurance contributions of further capital, move into new markets or within three months of starting in business. market niches. The switch from partnership Low cost – no legal formalities mean there to private limited company expands the num- is little administrative costs to setting up ber of manager / owners, moves and rear- as a sole trader. -

Nordic States Almanac 2018

Going north DENMARK FINLAND NORWAY SWEDEN Nordic States Almanac 2018 Heading up north „If investment is the driving force behind all economic development and going cross-border is now the norm on the European continent, good advisors provide both map and sounding-line for the investor.” Rödl & Partner „We also invest in the future! To ensure that our tradition is preserved, we encourage young talents and involve them directly into our repertoire. At first, they make up the top of our human towers and, with more experience, they take responsibility for the stability of our ambitious endeavours.” Castellers de Barcelona 3 Table of contents A. Introduction 6 B. Map 8 C. Countries, figures, people 9 I. Demographics 9 II. Largest cities 11 III. Country ratings 12 IV. Currencies 16 IV. Norway and the EU 16 VI. Inflation rates 17 VII. Growth 18 VIII. Major trading partners 19 IX. Transactions with Germany 22 X. Overview of public holidays in 2018 23 D. Law 27 I. Establishing a company 27 II. Working 35 III. Insolvency – obligations and risks 47 IV. Signing of contracts 50 V. Securing of receivables 54 VI. Legal disputes 57 E. Taxes 65 I. Tax rates 65 II. VAT – obligation to register for VAT 68 4 III. Personal income tax – tax liability for foreign employees 72 IV. Corporate income tax – criteria for permanent establishment (national) 74 V. Tax deadlines 75 VI. Transfer pricing 78 F. Accounting 84 I. Submission dates for annual financial statements 84 II. Contents / Structure of annual financial statements 85 III. Acceptable accounting standards 86 G. -

Partnership Agreement Example

Partnership Agreement Example THIS PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT is made this __________ day of ___________, 20__, by and between the following individuals: Address: __________________________ ___________________________ City/State/ZIP:______________________ Address: __________________________ ___________________________ City/State/ZIP:______________________ 1. Nature of Business. The partners listed above hereby agree that they shall be considered partners in business for the following purpose: ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ 2. Name. The partnership shall be conducted under the name of ________________ and shall maintain offices at [STREET ADDRESS], [CITY, STATE, ZIP]. 3. Day-To-Day Operation. The partners shall provide their full-time services and best efforts on behalf of the partnership. No partner shall receive a salary for services rendered to the partnership. Each partner shall have equal rights to manage and control the partnership and its business. Should there be differences between the partners concerning ordinary business matters, a decision shall be made by unanimous vote. It is understood that the partners may elect one of the partners to conduct the day-to-day business of the partnership; however, no partner shall be able to bind the partnership by act or contract to any liability exceeding $_________ without the prior written consent of each partner. 4. Capital Contribution. The capital contribution of -

Limited Liability Partnerships

inbrief Limited Liability Partnerships Inside Key features Incorporation and administration Members’ Agreements Taxation inbrief Introduction Key features • any members’ agreement is a confidential Introduction document; and It first became possible to incorporate limited Originally conceived as a vehicle liability partnerships (“LLPs”) in the UK in 2001 • the accounting and filing requirements are for use by professional practices to after the Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2000 essentially the same as those for a company. obtain the benefit of limited liability came into force. LLPs have an interesting An LLP can be incorporated with two or more background. In the late 1990s some of the major while retaining the tax advantages of members. A company can be a member of an UK accountancy firms faced big negligence claims a partnership, LLPs have a far wider LLP. As noted, it is a distinct legal entity from its and were experiencing a difficult market for use as is evidenced by their increasing members and, accordingly, can contract and own professional indemnity insurance. Their lobbying property in its own right. In this respect, as in popularity as an alternative business of the Government led to the introduction of many others, an LLP is more akin to a company vehicle in a wide range of sectors. the Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2000 which than a partnership. The members of an LLP, like gave birth to the LLP as a new business vehicle in the shareholders of a company, have limited the UK. LLPs were originally seen as vehicles for liability. As he is an agent, when a member professional services partnerships as demonstrated contracts on behalf of the LLP, he binds the LLP as by the almost immediate conversion of the major a director would bind a company. -

Basic Concepts Page 1 PARTNERSHIP ACCOUNTING

Dr. M. D. Chase Long Beach State University Advanced Accounting 1305-87B Partnership Accounting: Basic Concepts Page 1 PARTNERSHIP ACCOUNTING I. Basic Concepts of Partnership Accounting A. What is A Partnership?: An association of two or more persons to carry on as co-owners of a business for a profit; the basic rules of partnerships were defined by Congress: 1. Uniform Partnership Act of 1914 (general partnerships) 2. Uniform Limited Partnership Act of 1916 (limited partnerships) B. Characteristics of a Partnership: 1. Limited Life--dissolved by death, retirement, incapacity, bankruptcy etc 2. Mutual agency--partners are bound by each others’ acts 3. Unlimited Liability of the partners--the partnership is not a legal or taxable entity and therefore all debts and legal matters are the responsibility of the partners. 4. Co-ownership of partnership assets--all assets contributed to the partnership are owned by the individual partners in accordance with the terms of the partnership agreement; or equally if no agreement exists. C. The Partnership Agreement: A contract (oral or written) which can be used to modify the general partnership rules; partnership agreements at a minimum should cover the following: 1. Names or Partners and Partnership; 2. Effective date of the partnership contract and date of termination if applicable; 3. Nature of the business; 4. Place of business operations; 5. Amount of each partners capital and the valuation of each asset contributed and date the valuation was made; 6. Rights and responsibilities of each partner; 7. Dates of partnership accounting period; minimum capital investments for each partner and methods of determining equity balances (average, weighted average, year-end etc.) 8. -

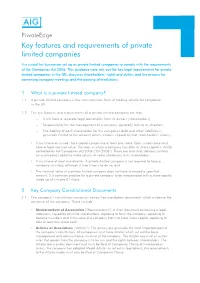

AIG Guide to Key Features of Private Limited Companies

PrivateEdge Key features and requirements of private limited companies It is crucial for businesses set up as private limited companies to comply with the requirements of the Companies Act 2006. This guidance note sets out the key legal requirements for private limited companies in the UK, discusses shareholders’ rights and duties, and the process for convening company meetings and the passing of resolutions 1 What is a private limited company? 1.1 A private limited company is the most common form of trading vehicle for companies in the UK. 1.2 The key features and requirements of a private limited company are that: – It will have a separate legal personality from its owners (shareholders). – Responsibility for the management of a company generally falls to its directors; – The liability of each shareholder for the company's debt and other liabilities is generally limited to the amount which remains unpaid on that shareholder's shares; • It must have an issued share capital comprising at least one share. Each issued share must have a fixed nominal value. The ways in which a company can alter its share capital is strictly controlled by the Companies Act 2006 (“CA 2006”). There are also strict statutory controls on a company's ability to make returns of value (dividends) to its shareholders; • It must have at least one director. A private limited company is not required to have a company secretary, although it may choose to do so; and • The nominal value of a private limited company does not have to exceed a specified amount. It is common practice for a private company to be incorporated with a share capital made up of just one £1 share.