SC Bat Conservation Plan CH 3: Species Accounts 49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mitochondrial Genomes of Palaeopteran Insects and Insights

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The mitochondrial genomes of palaeopteran insects and insights into the early insect relationships Nan Song1*, Xinxin Li1, Xinming Yin1, Xinghao Li1, Jian Yin2 & Pengliang Pan2 Phylogenetic relationships of basal insects remain a matter of discussion. In particular, the relationships among Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera are the focus of debate. In this study, we used a next-generation sequencing approach to reconstruct new mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) from 18 species of basal insects, including six representatives of Ephemeroptera and 11 of Odonata, plus one species belonging to Zygentoma. We then compared the structures of the newly sequenced mitogenomes. A tRNA gene cluster of IMQM was found in three ephemeropteran species, which may serve as a potential synapomorphy for the family Heptageniidae. Combined with published insect mitogenome sequences, we constructed a data matrix with all 37 mitochondrial genes of 85 taxa, which had a sampling concentrating on the palaeopteran lineages. Phylogenetic analyses were performed based on various data coding schemes, using maximum likelihood and Bayesian inferences under diferent models of sequence evolution. Our results generally recovered Zygentoma as a monophyletic group, which formed a sister group to Pterygota. This confrmed the relatively primitive position of Zygentoma to Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera. Analyses using site-heterogeneous CAT-GTR model strongly supported the Palaeoptera clade, with the monophyletic Ephemeroptera being sister to the monophyletic Odonata. In addition, a sister group relationship between Palaeoptera and Neoptera was supported by the current mitogenomic data. Te acquisition of wings and of ability of fight contribute to the success of insects in the planet. -

Aquatic Insects Are Dramatically Underrepresented in Genomic Research

insects Communication Aquatic Insects Are Dramatically Underrepresented in Genomic Research Scott Hotaling 1,* , Joanna L. Kelley 1 and Paul B. Frandsen 2,3,* 1 School of Biological Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84062, USA 3 Data Science Lab, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20002, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (P.B.F.); Tel.: +1-(828)-507-9950 (S.H.); +1-(801)-422-2283 (P.B.F.) Received: 20 August 2020; Accepted: 3 September 2020; Published: 5 September 2020 Simple Summary: The genome is the basic evolutionary unit underpinning life on Earth. Knowing its sequence, including the many thousands of genes coding for proteins in an organism, empowers scientific discovery for both the focal organism and related species. Aquatic insects represent 10% of all insect diversity, can be found on every continent except Antarctica, and are key components of freshwater ecosystems. However, aquatic insect genome biology lags dramatically behind that of terrestrial insects. If genomic effort was spread evenly, one aquatic insect genome would be sequenced for every ~9 terrestrial insect genomes. Instead, ~24 terrestrial insect genomes have been sequenced for every aquatic insect genome. A lack of aquatic genomes is limiting research progress in the field at both fundamental and applied scales. We argue that the limited availability of aquatic insect genomes is not due to practical limitations—small body sizes or overly complex genomes—but instead reflects a lack of research interest. We call for targeted efforts to expand the availability of aquatic insect genomic resources to empower future research. -

33245 02 Inside Front Cover

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU 186 BATS OF RAVENNA VOL. 106 Bats of Ravenna Training and Logistics Site, Portage and Trumbull Counties, Ohio1 VIRGIL BRACK, JR.2 AND JASON A. DUFFEY, Center for North American Bat Research and Conservation, Department of Ecology and Organismal Biology, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47089; Environmental Solutions & Innovations, Inc., 781 Neeb Road, Cincinnati, OH 45233 ABSTRACT. Six species of bats (n = 272) were caught at Ravenna Training and Logistics Site during summer 2004: 122 big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus), 100 little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus), 26 red bats (Lasiurus borealis), 19 northern myotis (Myotis septentrionalis), three hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus), and two eastern pipistrelles (Pipistrellus subflavus). Catch was 9.7 bats/net site (SD = 10.2) and 2.4 bats/net night (SD = 2.6). No bats were captured at two net sites and only one bat was caught at one site; the largest captures were 33, 36, and 37 individuals. Five of six species were caught at two sites, 2.7 (SD = 1.4) species were caught per net site, and MacArthur’s diversity index was 2.88. Evidence of reproduction was obtained for all species. Chi-square tests indicated no difference in catch of males and reproductive females in any species or all species combined. Evidence was found of two maternity colonies each of big brown bats and little brown myotis. Capture of big brown bats (X2 = 53.738; P <0.001), little brown myotis (X2 = 21.900; P <0.001), and all species combined (X2 = 49.066; P <0.001) was greatest 1 – 2 hours after sunset. -

Bat Distribution in the Forested Region of Northwestern California

BAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE FORESTED REGION OF NORTHWESTERN CALIFORNIA Prepared by: Prepared for: Elizabeth D. Pierson, Ph.D. California Department of Fish and Game William E. Rainey, Ph.D. Wildlife Management Division 2556 Hilgard Avenue Non Game Bird and Mammal Section Berkeley, CA 9470 1416 Ninth Street (510) 845-5313 Sacramento, CA 95814 (510) 548-8528 FAX [email protected] Contract #FG-5123-WM November 2007 Pierson and Rainey – Forest Bats of Northwestern California 2 Pierson and Rainey – Forest Bats of Northwestern California 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bat surveys were conducted in 1997 in the forested regions of northwestern California. Based on museum and literature records, seventeen species were known to occur in this region. All seventeen were identified during this study: fourteen by capture and release, and three by acoustic detection only (Euderma maculatum, Eumops perotis, and Lasiurus blossevillii). Mist-netting was conducted at nineteen sites in a six county area. There were marked differences among sites both in the number of individuals captured per unit effort and the number of species encountered. The five most frequently encountered species in net captures were: Myotis yumanensis, Lasionycteris noctivagans, Myotis lucifugus, Eptesicus fuscus, and Myotis californicus; the five least common were Pipistrellus hesperus, Myotis volans, Lasiurus cinereus, Myotis ciliolabrum, and Tadarida brasiliensis. Twelve species were confirmed as having reproductive populations in the study area. Sampling sites were assigned to a habitat class: young growth (YG), multi-age stand (MA), old growth (OG), and rock dominated (RK). There was a significant response to habitat class for the number of bats captured, and a trend towards differences for number of species detected. -

Range Expansion of Lymantria Dispar Dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) Along Its North‐Western Margin in North America Despite Low Predicted Climatic Suitability

Received: 22 December 2017 | Revised: 9 August 2018 | Accepted: 11 September 2018 DOI: 10.1111/jbi.13474 RESEARCH PAPER Range expansion of Lymantria dispar dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) along its north‐western margin in North America despite low predicted climatic suitability Marissa A. Streifel1,2 | Patrick C. Tobin3 | Aubree M. Kees1 | Brian H. Aukema1 1Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota Abstract 2Minnesota Department of Agriculture, Aim: The European gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar dispar (L.), (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) St. Paul, Minnesota is an invasive defoliator that has been expanding its range in North America follow- 3School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, ing its introduction in 1869. Here, we investigate recent range expansion into a Washington region previously predicted to be climatically unsuitable. We examine whether win- Correspondence ter severity is correlated with summer trap captures of male moths at the landscape Brian Aukema, Department of Entomology, scale, and quantify overwintering egg survivorship along a northern boundary of the University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN. Email: [email protected] invasion edge. Location: Northern Minnesota, USA. Funding information USDA APHIS, Grant/Award Number: Methods: Several winter severity metrics were defined using daily temperature data A-83114 13255; National Science from 17 weather stations across the study area. These metrics were used to explore Foundation, Grant/Award Number: – ‐ 1556111; United States Department of associations with male gypsy moth monitoring data (2004 2014). Laboratory reared Agriculture Animal Plant Health Inspection egg masses were deployed to field locations each fall for 2 years in a 2 × 2 factorial Service, Grant/Award Number: 15-8130- / × / 0577-CA; USDA Forest Service, Grant/ design (north south aspect below above snow line) to reflect microclimate varia- Award Number: 14-JV-11242303-128 tion. -

Roost Characteristics and Clustering Behavior of Western Red Bats (Lasiurus Blossevillii) in Southwestern New Mexico

Western North American Naturalist Volume 78 Number 2 Article 7 7-19-2018 Roost characteristics and clustering behavior of western red bats (Lasiurus blossevillii) in southwestern New Mexico Brett R. Andersen Biology Department, University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, NE, [email protected] Keith Geluso Biology Department, University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, NE, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Andersen, Brett R. and Geluso, Keith (2018) "Roost characteristics and clustering behavior of western red bats (Lasiurus blossevillii) in southwestern New Mexico," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 78 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol78/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 78(2), © 2018, pp. 174–183 Roost characteristics and clustering behavior of western red bats (Lasiurus blossevillii) in southwestern New Mexico BRETT R. ANDERSEN1,* AND KEITH GELUSO1 1Biology Department, University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, NE 68849 ABSTRACT.—The western red bat (Lasiurus blossevillii) is a foliage-roosting species of riparian habitats in arid regions of the southwestern United States. Only limited published anecdotal observations exist for roost sites used by this species. Western red bats were split taxonomically from the eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis) in 1988, but summaries of roosting behaviors for western red bats still appear to stem from former associations with the commonly studied eastern red bat. -

Forest Management and Bats

F orest Management a n d B a t s | 1 Forest Management and Bats F orest Management a n d B a t s | 2 Bat Basics More than 1,400 species of bats account for almost a quarter of all mammal species worldwide. Bats are exceptionally vulnerable to population losses, in part because they are one of the slowest-reproducing mammals on Earth for their size, with most producing only one young each year. For their size, bats are among the world’s longest-lived mammals. The little brown bat can live up to 34 years in the wild. Contrary to popular misconceptions, bats are not blind and do not become entangled in human hair. Bats are the only mammals capable of true flight. Most bat species use an extremely sophisticated biological sonar, called echolocation, to navigate and hunt for food. Some bats can detect an object as fine as a human hair in total darkness. Worldwide, bats are a primary predator of night-flying Merlin Tuttle insects. A single little brown bat, a resident of North American forests, can consume 1,000 mosquito-sized insects in just one hour. All but three of the 47 species of bats found in the United States and Canada feed solely on insects, including many destructive agricultural pests. The remaining bat species feed on nectar, pollen, and the fruit of cacti and agaves and play an important role in pollination and seed dispersal in southwestern deserts. The 15 million Mexican free-tailed bats at Bracken Cave, Texas, consume approximately 200 tons of insects nightly. -

Nine Species of Bats, Each Relying on Specific Summer and Winter Habitats

Species Guide to Vermont Bats • Vermont has nine species of bats, each relying on specific summer and winter habitats. • Six species hibernate in caves and mines during the winter (cave bats). • During the summer, two species primarily roost in structures (house bats), • And four roost in trees and rocky outcrops (forest bats). • Three species migrate south to warmer climates for the winter and roost in trees during the summer (migratory bats). • This guide is designed to help familiarize you with the physical characteristics of each species. • Bats should only be handled by trained professionals with gloves. • For more information, contact a bat biologist at the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department or go to www.vtfishandwildlife.com Vermont’s Nine Species of Bats Cave Bats Migratory Tree Bats Eastern small-footed bat Silver-haired bat State Threatened Big brown bat Northern long-eared bat Indiana bat Federally Threatened State Endangered J Chenger Federally and State J Kiser Endangered J Kiser Hoary bat Little brown bat Tri-colored bat Eastern red bat State State Endangered Endangered Bat Anatomy Dr. J. Scott Altenbach http://jhupressblog.com House Bats Big brown bat Little brown bat These are the two bat species that are most commonly found in Vermont buildings. The little brown bat is state endangered, so care must be used to safely exclude unwanted bats from buildings. Follow the best management practices found at www.vtfishandwildlife.com/wildlife_bats.cfm House Bats Big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus Big thick muzzle Weight 13-25 g Total Length (with Tail) 106 – 127 mm Long silky Wingspan 32 – 35 cm fur Forearm 45 – 48 mm Description • Long, glossy brown fur • Belly paler than back • Black wings • Big thick muzzle • Keeled calcar Similar Species Little brown bat is much Commonly found in houses smaller & lacks keeled calcar. -

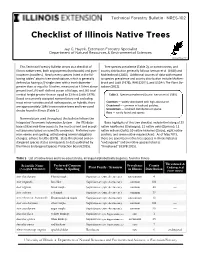

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

Corynorhinus Townsendii): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project October 25, 2006 Jeffery C. Gruver1 and Douglas A. Keinath2 with life cycle model by Dave McDonald3 and Takeshi Ise3 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada 2Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Old Biochemistry Bldg, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82070 3Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3166, Laramie, WY 82071 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Gruver, J.C. and D.A. Keinath (2006, October 25). Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/townsendsbigearedbat.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the modeling expertise of Dr. Dave McDonald and Takeshi Ise, who constructed the life-cycle analysis. Additional thanks are extended to the staff of the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for technical assistance with GIS and general support. Finally, we extend sincere thanks to Gary Patton for his editorial guidance and patience. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Jeff Gruver, formerly with the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Biological Sciences program at the University of Calgary where he is investigating the physiological ecology of bats in northern arid climates. He has been involved in bat research for over 8 years in the Pacific Northwest, the Rocky Mountains, and the Badlands of southern Alberta. He earned a B.S. in Economics (1993) from Penn State University and an M.S. -

Species Assessment for Little Brown Myotis

Species Status Assessment Class: Mammalia Family: Vespertilionidae Scientific Name: Myotis lucifugus Common Name: Little brown myotis Species synopsis: The little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus), formerly called the “little brown bat,” has long been considered one of the most common and widespread bat species in North America. Its distribution spans from the southern limits of boreal forest habitat in southern Alaska and the southern half of Canada throughout most of the contiguous United States, excluding the southern Great Plains and the southeast area of California. In the southwestern part of the historic range, a formerly considered subspecies identified as Myotis lucifugus occultus, is now considered a distinct species, Myotis occultus (Piaggio et al. 2002, Wilson and Reeder 2005). Available literature indicates that the northeastern U.S. constitutes the core range for this species, and that population substantially decreases both southward and westward from that core range (Davis et al. 1965, Humphrey and Cope 1970). New York was the first state affected by white-nose syndrome (WNS), a disease characterized by the presence of an unusual fungal infection and aberrant behavior in hibernating bats. The pre-WNS population was viable and did not face imminent risk of extinction. However, a once stable outlook quickly reversed with the appearance of WNS in 2006, which dramatically altered the population balance and has substantially impaired the ability of the species to adapt to other cumulative threats against a rapidly declining baseline. In January 2012, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) biologists estimated that at least 5.7 million to 6.7 million bats had died from WNS (USFWS 2012). -

Lasiurus Ega (Southern Yellow Bat)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Lasiurus ega (Southern Yellow Bat) Family: Vespertilionidae (Vesper or Evening Bats) Order: Chiroptera (Bats) Class: Mammalia (Mammals) Fig. 1. Southern yellow bat, Lasiurus ega. [http://www.collett-trust.org/uploads/Dasypterus%20ega5.jpg, downloaded 16 February 2016] TRAITS. Lasiurus ega is medium sized with relatively long ears and dull yellow/orange fur (Fig. 1). The span of its wing is approximately 35cm. Its mean body length is 11.8cm; tail length, 5.1cm; foot length, 0.90cm and forearm length 4.7cm and its mass ranges from 10-18g; however, the males are smaller in length and size than the females. They have a short body with a lateral projection of the upper lip and short, rounded ears (Fig. 2). The digits shorten from the 3rd to the 5th finger. Each female possesses 4 mammae whereas the males have a distally spiny penis (Kurta and Lehr, 1995). DISTRIBUTION. Found from the southwestern United States to northern Argentina and Uruguay; also can be found in Mexico and Central America (Fig. 3). The southern yellow bat is native to Trinidad. It has a seasonal migratory pattern in which it moves from the north to avoid the harsh/cold conditions (Encyclopedia of Life, 2016). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. The habitat of the southern yellow bat is forest which has a lot of wooded surroundings, foliage as well as palms. The bat is nocturnal in nature. Sometimes it inhabits thatched roofing and corn stalks that are dried, however they avoid entering mountainous areas.