Programnotes Dewaart Mozart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

Mozart's Very First Horn Concerto

48 HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL MOZART'SVERY FIRST HORN CONCERTO Herman Jeurissen (Translated by Martha Bixler, Ellen Callmann and Richard Sacksteder) olfgang Amadeus Mozart's four horn concertos belong to the standard repertory of every horn player today. There are, in addition, some fragments indicating that Mozart had in mind at least two more concertos. All of these worksw stem from Mozart's years in Vienna from 1781 to the end of his life. Mozart sketched out the Rondo KV 371 on March 21,178 1, five days after he had left Munich at the command of his patron, Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo, to join the court musicians of Salzburg in Vienna to give musical luster to the festivities in honor of the newly crowned emperor, Joseph 11. He must havecomposed thedraft of an opening allegro, KV 370b, for a horn concerto in E-flat major at about the same time. In all probability, the Rondo KV 371 formed its finale. The themes of this experimental concerto, KV370b+371, are completely characteristic of Mozart: the march-like open- ing of the first movement occurs frequently in the piano concertos and the rondo theme set in 214 time anticipates the second finale of Figaro (Ex. 1). No trace has been found of plans he probably had for a second movement. Example 1 The Allegro KV 370b In 1856, Mozart's son Carl Thomas (1784-1858), in connection with his father's 100th birthday, cut up a large part of this first movement and distributed the pieces as "Mozart relics." Today, 127 measures of this movement survive, in which, as in the Rondo, the horn part is fully worked out while the accompaniment is only partially indicated. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Interpretation of Mozart Concertos with an Historical View

Kurs: CA 1004 30 hp 2018 Master in Music 120 ECTS Institutionen för Klassisk musik Handledare: Katarina Ström-Harg Examinator: Ronny Lindeborg Mónica Berenguer Caro Interpretation of Mozart concertos with an historical view 1 Preface The basis of this research originally came from my passion for my instrument. I started to think about the importance of Mozart's concertos about 4 years ago, when I began taking orchestra auditions and competitions. A horn player will perform Mozart concertos through his entire musical career, so I think it is necessary to know more about them. I hope to contribute to knowledge for new and future students and I hope that they will be able to access to the content of my thesis whenever they need it. In fact, I may have not achieved my current level of success without a strong support group. First, my parents, who have supported me with love and understanding. Secondly there are my teachers, Katarina Ström-Harg and Annamia Larsson, each of whom has provided patient advices and guidance throughout the research process. Thank you all for your unwavering support. 2 Abstract This thesis is an historical, technical and stylistic investigation of Mozart horn concertos. It includes a description of Mozart’s life; the moment in his life where the concertos were developed. It contains information about Ignaz Leitgeb, the horn player who has a close friendship with Mozart. Also, the explanation of his technical characteristics of the natural horn and the way of Mozart deal with the resources and limitations of this instrument, as well as the way of the interpretation of these pieces had been facilitated by the arrival of the chromatic horn. -

Commemorative Concert the Suntory Music Award

Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Suntory Foundation for Arts ●Abbreviations picc Piccolo p-p Prepared piano S Soprano fl Flute org Organ Ms Mezzo-soprano A-fl Alto flute cemb Cembalo, Harpsichord A Alto fl.trv Flauto traverso, Baroque flute cimb Cimbalom T Tenor ob Oboe cel Celesta Br Baritone obd’a Oboe d’amore harm Harmonium Bs Bass e.hrn English horn, cor anglais ond.m Ondes Martenot b-sop Boy soprano cl Clarinet acc Accordion F-chor Female chorus B-cl Bass Clarinet E-k Electric Keyboard M-chor Male chorus fg Bassoon, Fagot synth Synthesizer Mix-chor Mixed chorus c.fg Contrabassoon, Contrafagot electro Electro acoustic music C-chor Children chorus rec Recorder mar Marimba n Narrator hrn Horn xylo Xylophone vo Vocal or Voice tp Trumpet vib Vibraphone cond Conductor tb Trombone h-b Handbell orch Orchestra sax Saxophone timp Timpani brass Brass ensemble euph Euphonium perc Percussion wind Wind ensemble tub Tuba hichi Hichiriki b. … Baroque … vn Violin ryu Ryuteki Elec… Electric… va Viola shaku Shakuhachi str. … String … vc Violoncello shino Shinobue ch. … Chamber… cb Contrabass shami Shamisen, Sangen ch-orch Chamber Orchestra viol Violone 17-gen Jushichi-gen-so …ens … Ensemble g Guitar 20-gen Niju-gen-so …tri … Trio hp Harp 25-gen Nijugo-gen-so …qu … Quartet banj Banjo …qt … Quintet mand Mandolin …ins … Instruments p Piano J-ins Japanese instruments ● Titles in italics : Works commissioned by the Suntory Foudation for Arts Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Awardees and concert details, commissioned works 1974 In Celebration of the 5thAnniversary of Torii Music Award Ⅰ Organ Committee of International Christian University 6 Aug. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

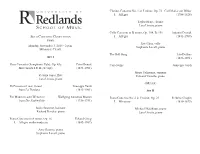

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart – Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Mozart entered this concerto in his catalog on February 10, 1785, and performed the solo in the premiere the next day in Vienna. The orchestra consists of one flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. At these concerts, Shai Wosner plays Beethoven’s cadenza in the first movement and his own cadenza in the finale. Performance time is approximately thirty-four minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20 were given at Orchestra Hall on January 14 and 15, 1916, with Ossip Gabrilowitsch as soloist and Frederick Stock conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on March 15, 16, and 17, 2007, with Mitsuko Uchida conducting from the keyboard. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 6, 1961, with John Browning as soloist and Josef Krips conducting, and most recently on July 8, 2007, with Jonathan Biss as soloist and James Conlon conducting. This is the Mozart piano concerto that Beethoven admired above all others. It’s the only one he played in public (and the only one for which he wrote cadenzas). Throughout the nineteenth century, it was the sole concerto by Mozart that was regularly performed—its demonic power and dark beauty spoke to musicians who had been raised on Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt. -

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao's Piano Concerto, Op. 53

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao’s Piano Concerto, Op. 53: A Comparison with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lin-Min Chang, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Anna Gowboy Dr. Kia-Hui Tan Copyright by Lin-Min Chang 2018 2 ABSTRACT One of the most prominent Taiwanese composers, Tyzen Hsiao, is known as the “Sergei Rachmaninoff of Taiwan.” The primary purpose of this document is to compare and discuss his Piano Concerto Op. 53, from a performer’s perspective, with the Second Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Hsiao’s preferences of musical materials such as harmony, texture, and rhythmic patterns are influenced by Romantic, Impressionist, and 20th century musicians incorporating these elements together with Taiwanese folk song into a unique musical style. This document consists of four chapters. The first chapter introduces Hsiao’s biography and his musical style; the second chapter focuses on analyzing Hsiao’s Piano Concerto Op. 53 in C minor from a performer’s perspective; the third chapter is a comparison of Hsiao and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos regarding the similarities of orchestration and structure, rhythm and technique, phrasing and articulation, harmony and texture. The chapter also covers the differences in the function of the cadenza, and the interaction between solo piano and orchestra; and the final chapter provides some performance suggestions to the practical issues in regard to phrasing, voicing, technique, color, pedaling, and articulation of Hsiao’s Piano Concerto from the perspective of a pianist. -

(1756-1791) Completed Wind Concertos: Baroque and Classical Designs in the Rondos of the Final Movements

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's (1756-1791) Completed Wind Concertos: Baroque and Classical Designs in the Rondos of the Final Movements Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Koner, Karen Michelle Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:25:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193304 1 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s (1756-1791) Completed Wind Concertos: Baroque and Classical Designs in the Rondos of the Final Movements By Karen Koner __________________________________ Copyright © Karen Koner 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Music In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music In the Graduate College The University of Arizona 2008 2 STATEMENT BY THE AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. Signed: Karen Koner Approval By Thesis Director This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: J. Timothy Kolosick 4/30/2008 Dr. -

A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels Achareeya Fukiat Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Fukiat, Achareeya, "A Survey of Selected Piano Concerti for Elementary, Intermediate, and Early-Advanced Levels" (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5630. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5630 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF SELECTED PIANO CONCERTI FOR ELEMENTARY, INTERMEDIATE, AND EARLY-ADVANCED LEVELS Achareeya Fukiat A Doctoral Research Project submitted to College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance James Miltenberger,