Warhol Mapplethorpe Labels.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Incurable Cancer Patient at the End of Life

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1013 _____________________________ _____________________________ The Incurable Cancer Patient at the End of Life Medical Care Utilization, Quality of Life and the Additive Analgesic Effect of Paracetamol in Concurrent Morphine Therapy BY BERTIL AXELSSON ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2001 Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine) in General Surgery, presented at Uppsala University in 2001 ABSTRACT Axelsson, B. 2001. The incurable cancer patient at the end of life. Medical care utilization, quality of life and the additive analgesic effect of paracetamol in concurrent morphine therapy. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1013. 88 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-4968-9. Optimal quality of life and health care utilization are objectives of all palliative services. The aim of this study was to present background data on health care utilization and quality of life, explore potential outcome variables of health care utilization, evaluate a hospital-based palliative support service, provide a quality of life tool specially designed for incurable patients at the end of life and to establish whether paracetamol has an additive analgesic effect to morphine. Only 12% of the patients died at home. When the period between diagnosis and death was less than one month, every patient died in an institution. Younger patients, married patients, and those living within a 40 km radius of the hospital utilized more hospital days. The "length of terminal hospitalization" and the "proportion of days at home/total inclusion days" seemed to be feasible outcome variables when evaluating a palliative support service. -

Chapter One - Sledgehammer

Chapter One - Sledgehammer. Davin Grey picked his way along a crowded footpath into a mild autumn breeze that ruffled the hair of morning commuters. The thump of a tram crunching along the tracks down Collins Street was one of those deliciously iconic sounds that reminded Davin why he had moved to Melbourne. It spoke of industry and commerce, movement and energy, urgency and connection. Here, people had purpose and direction. Here, you weren’t judged. You could blend in and get on with your life. Make your own future. A far cry, Davin thought, from the malaise of the country town he grew up in. It was a relief to escape that myopic environment and the small mindedness of the people he’d grown up with. That seemed a lifetime ago. Back then, he wasn’t Grey, he was Gaye - a family name of which his father was fiercely proud. It was, as he would remind Davin often in his formative years, of ancient Gallic lineage stretching back to the Norman Conquests in 1066. ‘It’s from an Old French word: gai’, his dad would say. ‘Means full of joy.’ And so would begin a recurrent sermon Davin would endure many times over the years. ‘There are Gayes in our family who we should never forget, Davin, Gayes who have made the ultimate sacrifice,’ he would add, nodding to a hallway lined with sepia photographs of men in uniform. ‘Your name – our name – is etched in headstones at Flanders Fields and Vietnam.’ On occasion, Mr Gaye would bring out his musty collection of Motown records. -

Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera

How To Quote This Material ©Jack Fritscher www.JackFritscher.com Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera — Take 2: Pentimento for Robert Mapplethorpe Manuscript TAKE 2 © JackFritscher.com PENTIMENTO FOR ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE FETISHES, FACES, AND FLOWERS Of EVIL1 “He wanted to see the devil in us all... The man who liberated S&M Leather into international glamor... The man Jesse Helms hates... The man whose epic movie-biography only Ken Russell could re-create...” Photographer Mapplethorpe: The Whitney, the NEA and censorship, Schwarzenegger, Richard Gere, Susan Sarandon, Paloma Picasso, Hockney, Warhol, Patti Smith, Scavullo, sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll, S&M, flowers, black leather, fists, Allen Ginsberg, and, once-upon-a-time, me... The pre-AIDS past of the 1970s has become a strange country. We lived life differently a dozen years ago. The High Time was in full upswing. Liberation was in the air, and so were we, performing nightly our high-wire sex acts in a circus without nets. If we fell, we fell with splendor in the grass. That carnival, ended now, has no more memory than the remembrance we give it, and we give remembrance here. In 1977, Robert Mapplethorpe arrived unexpectedly in my life. I was editor of the San Francisco—based international leather magazine, Drummer, and Robert was a New York shock-and-fetish photographer on the way up. Drummer wanted good photos. Robert, already infamous for his leather S&M portraits, always seeking new models with outrageous trips, wanted more specific exposure within the leather community. Our mutual, professional want ignited almost instantly into mutual, personal passion. -

PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016

/robertmillergallery For immediate release: [email protected] @RMillerGallery 212.366.4774 /robertmillergallery PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016 New York, NY – February 17, 2016. Robert Miller Gallery is pleased to announce Eighteen Stations, a special project by Patti Smith. Eighteen Stations revolves around the world of M Train, Smith’s bestselling book released in 2015. M Train chronicles, as Smith describes, “a roadmap to my life,” as told from the seats of the cafés and dwellings she has worked from globally. Reflecting the themes and sensibility of the book, Eighteen Stations is a meditation on the act of artistic creation. It features the artist’s illustrative photographs that accompany the book’s pages, along with works by Smith that speak to art and literature’s potential to offer hope and consolation. The artist will be reading from M Train at the Gallery throughout the run of the exhibition. Patti Smith (b. 1946) has been represented by Robert Miller Gallery since her joint debut with Robert Mapplethorpe, Film and Stills, opened at its 724 Fifth Avenue location in 1978. Recent solo exhibitions at the Gallery include Veil (2009) and A Pythagorean Traveler (2006). In 2014 Rockaway Artist Alliance and MoMA PS1 mounted Patti Smith: Resilience of the Dreamer at Fort Tilden, as part of a special project recognizing the ongoing recovery of the Rockaway Peninsula, where the artist has a home. Smith's work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at institutions worldwide including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2013); Detroit Institute of Arts (2012); Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford (2011); Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporaine, Paris (2008); Haus der Kunst, Munich (2003); and The Andy Warhol Museum (2002). -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

A Selective Study of the Writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses The literary dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925: A selective study of the writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler. Vrba, Marya How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Vrba, Marya (2011) The literary dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925: A selective study of the writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42396 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ The Literary Dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925 A Selective Study of the Writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler Mary a Vrba Thesis submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Modern Languages Swansea University 2011 ProQuest Number: 10798104 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Art in America, March 1, 2016. Robert Mapplethorpe

Reid-Pharr, Robert. “Putting Mapplethorpe In His Place,” Art in America, March 1, 2016. Robert Mapplethorpe: Self-Portrait, 1988, platinum print, 23⅛ by 19 inches. With a retrospective for the celebrated photographer about to open at two Los Angeles institutions, the author reassesses the 1990 “X Portfolio” obscenity trial, challenging its distinction between fine art and pornography. Americans take their art seriously. Stereotypes about Yankee simplicity and boorishness notwithstanding, we are a people ever ready to challenge each other’s tastes and orthodoxies. And though we always seem surprised when it happens, we can quite efficiently use the work of artists as screens against which to project deeply entrenched phobias regarding the nature of our society and culture. In hindsight it really was no surprise that the traveling retrospective “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment” would so fiercely grip the imaginations of artists, critics, politicians and laypersons alike. Curated by Janet Kardon of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in Philadelphia, the exhibition opened in December of 1988, just before the artist’s death in March of 1989. It incorporated some of Mapplethorpe’s best work, including stunning portraits and still lifes. What shocked and irritated some members of his audiences, however, were photographs of a naked young boy and a semi-naked girl as well as richly provocative erotic images of African-American men and highly stylized photographs of the BDSM underground in which Mapplethorpe participated. Indeed, much of what drew such concentrated attention to Mapplethorpe was the delicacy and precision with which he treated his sometimes challenging subject matter. -

Obessions and Promiscuities

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2003 Obessions and Promiscuities Azita Osanloo The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Osanloo, Azita, "Obessions and Promiscuities" (2003). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3112. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3112 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature / Yes, I grant permission " No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature: / A Date: 3 Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 OBSESSIONS AND PROMISCUITIES By Azita Osanloo B.A. Oberlin College, 2000 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts The University of Montana August 2 003 Approved by; c: rperson Dean, Graduate School • 3f, Date I ' UMI Number: EP35142 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

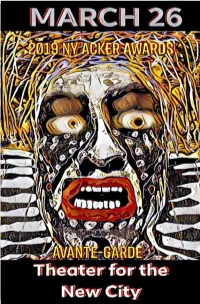

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

A Short History of the Wearing of Clerical Collars in the Presbyterian Tradition

A Short History of the Wearing of Clerical Collars in the Presbyterian Tradition Introduction There does not seem to have been any distinctive everyday dress for Christian pastors up until the 6th century or so. Clergy simply wore what was common, yet muted, modest, and tasteful, in keeping with their office. In time, however, the dress of pastors remained rather conservative, as it is want to do, while the dress of lay people changed more rapidly. The result was that the dress of Christian pastors became distinct from the laity and thus that clothing began to be invested (no pun intended) with meaning. Skipping ahead, due to the increasing acceptance of lay scholars in the new universities, the Fourth Lateran council (1215) mandated a distinctive dress for clergy so that they could be distinguished when about town. This attire became known as the vestis talaris or the cassock. Lay academics would wear an open front robe with a lirripium or hood. It is interesting to note that both modern day academic and clerical garb stems from the same Medieval origin. Councils of the Roman Catholic church after the time of the Reformation stipulated that the common everyday attire for priests should be the cassock. Up until the middle of the 20th century, this was the common street clothes attire for Roman Catholic priests. The origin of the clerical collar does not stem from the attire of Roman priests. It’s genesis is of protestant origin. The Origin of Reformed Clerical Dress In the time of the Reformation, many of the Reformed wanted to distance themselves from what was perceived as Roman clerical attire. -

Triptych Eyes of One on Another

Saturday, September 28, 2019, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Triptych Eyes of One on Another A Cal Performances Co-commission Produced by ArKtype/omas O. Kriegsmann in cooperation with e Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation Composed by Bryce Dessner Libretto by korde arrington tuttle Featuring words by Essex Hemphill and Patti Smith Directed by Kaneza Schaal Featuring Roomful of Teeth with Alicia Hall Moran and Isaiah Robinson Jennifer H. Newman, associate director/touring Lilleth Glimcher, associate director/development Brad Wells, music director and conductor Martell Ruffin, contributing choreographer and performer Carlos Soto, set and costume design Yuki Nakase, lighting design Simon Harding, video Dylan Goodhue/nomadsound.net, sound design William Knapp, production management Talvin Wilks and Christopher Myers, dramaturgy ArKtype/J.J. El-Far, managing producer William Brittelle, associate music director Kathrine R. Mitchell, lighting supervisor Moe Shahrooz, associate video designer Megan Schwarz Dickert, production stage manager Aren Carpenter, technical director Iyvon Edebiri, company manager Dominic Mekky, session copyist and score manager Gill Graham, consulting producer Carla Parisi/Kid Logic Media, public relations Cal Performances’ 2019 –20 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ROOMFUL OF TEETH Estelí Gomez, Martha Cluver, Augusta Caso, Virginia Kelsey, omas McCargar, ann Scoggin, Cameron Beauchamp, Eric Dudley SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS Lisa Oman, executive director ; Eric Dudley, artistic director Susan Freier, violin ; Christina Simpson, viola ; Stephen Harrison, cello ; Alicia Telford, French horn ; Jeff Anderle, clarinet/bass clarinet ; Kate Campbell, piano/harmonium ; Michael Downing and Divesh Karamchandani, percussion ; David Tanenbaum, guitar Music by Bryce Dessner is used with permission of Chester Music Ltd. “e Perfect Moment, For Robert Mapplethorpe” by Essex Hemphill, 1988. -

Robert Mapplethorpe

GALERIE THADDAEUS ROPAC ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE CURATED BY HEDI SLIMANE PARIS DEBELLEYME 13 Thursday - 19 Saturday The Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery is pleased to present an important exhibition of works by American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. Hedi Slimane, the artistic director of Dior Homme, also a photographer in his own right, will curate the show. The concept of the show is to invite a contemporary artist to rediscover a major body of work such as Mapplethorpe's, by reframing the whole, based on his own sensibilities and tastes thus helping us to view the renowned works in a new light. This show follows in the footsteps of a series of exhibits. Previous shows include- « Robert Mapplethorpe: Eye to Eye » organized in 2003 by the American artist Cindy Sherman in New York, as well as the exhibit « Robert Mapplethorpe curated by David Hockney » which took place in London in early 2005. Both Slimane and Mapplethorpe share a passion for photography, and both, by different means, each in his own generation, have defined the mood and aesthetic of the artistic community to which they belong. Hedi Slimane has been given free reign to explore themes that inspire him in Mapplethorpe's work. Last May, in conjunction with the release of his book of photographs of rocks bands, Slimane also edited the layout for the daily paper Libération. We can expect to find, in his selection of works for the show, images that reflect themes in both he and Mapplethorpe's lives where their sensibilities, moods and observations converge. By offering this face-to-face between two creative forces, this event allows us to revisit the work in an intimate, rather than critical manner.